Overview

Zambia is a country endowed with considerable environmental assets, including 44 million hectares of forest and a rich national park system covering some 19 percent of the total land area. Zambia is a vast low-income country with widespread rural poverty, though approximately 40 percent of the population lives in its urban centers. The Zambian economy remains dominated by subsistence agriculture and mining and has not undergone significant structural transformation. Other key industries serving as employment sources are wholesale and retail trade industry, and the community, social and personal services industry. Small-scale farming is the primary source of income in rural Zambia and 72 percent of the work force is employed in agriculture, yet it only accounts for less than 10 percent of its GDP. In general, the least productive land in Zambia is held under customary tenure by small farmers while the most productive land is leased for commercial farms, mining operations, and urban and tourism developments (UNDP 2016). This reflects Zambia’s colonial position, as Northern Rhodesia, with a relatively small area of crown land reserved for colonists for mining and agricultural development along a line of rail.

Almost 32 percent of land in Zambia is agricultural and 59 percent is forest area. Zambia’s high rate of deforestation—estimated at 250,000 to 300,000 hectares per year—Zambia is ranked as having one of the highest rates of deforestation in the world, approximately 2 percent per annum, and increasing (Lion Alert 2017).

Deforestation and degradation are a result of encroachment from agriculture, tree harvesting for fuel wood and sale, and uncontrolled burning. Lack of employment and low barrier to entry is a driving force in the charcoal trade: it requires limited investment and training, and can be used to generate quick income for other investments such as in agriculture (Gumbo et al. 2013). Improved productivity on Zambia’s abundant arable land has been held back by a lack of investment in rural infrastructure, extension services, and research and development. Zambia’s smallholder farmers are further constrained by a lack of documented, secure land rights (USAID 2014; Focus on Land in Africa 2016).

The 1995 Lands Act allows for conversion of customary tenure to state leasehold tenure with private leasehold interest. However, the conversion of customary land to large leaseholds has in other cases eroded local rights to common-pool resources and enclosed communal land, causing local people to lose access to water sources, grazing land, and forest products.

Persistent rural poverty has contributed to a high rate of migration to urban areas. Population growth and migration into Zambian cities has accelerated rapidly in the last decade. Two of Zambia’s largest cities, Lusaka and Kitwe, are expected to double in size over the next 20 years. However, the largest population growth rates are actually projected for smaller towns. These population shifts are also correlated with growth in the Zambian mining industry and increasing regional trade. The provision of public services and infrastructure is lagging behind urban growth (IGC 2016). These small towns (often district centers) were not initially planned for expansion and as a result there are challenges with respect to peri-urban development and planning as development encroaches into customary areas.

On 5 January 2016 Zambia finalized its new Constitution, which amends the Constitution of Zambia Act 1991. Land was among the most controversial provisions of the Constitution, going through numerous revisions and facing criticism from traditional leaders, who rejected the concept that land is vested in the Office of the President (though this had been a feature of the previous Constitution). The Constitution specifies the principles of land policy, environmental and natural resources management, provides the protection of natural resources and restricts their utilization, and establishes a Land Commission: “to administer, manage and alienate land, on behalf of the President.” The Constitution provides for: (1) equitable access to land and associated resources; (2) security of tenure for lawful land holders; (3) recognition of indigenous cultural rites; (4) sustainable use of land; (5) transparent and cost-effective management of land; (6) conservation and protection of ecologically sensitive areas; and (7) cost-effective and efficient settlement of land disputes; (8) river frontages, islands, lakeshores and ecologically and culturally sensitive areas be accessible to the public and maintained and used for conservation and preservation activities, and not to be leased, fenced or sold; (9) investments in land to also benefit local communities and their economy; and (10) plans for land use to be done in a consultative and participatory manner (GRZ 2016).

Key Issues and Intervention Constraints

Donors can help Zambia develop a more dynamic, productive, and sustainable economy by providing assistance in the following areas:

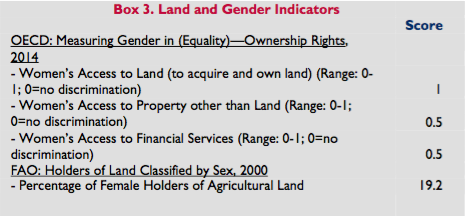

Many of Zambia’s ethnic groups practice matrilocal land inheritance patterns on customary land, where men relocate to their wives’ villages for part or all of their marriages. Inheritance patterns in many of these groups is matrilineal, where children inherit land from their mother’s family (often from uncles, rather than their fathers). In practice, it is not clear that these customs result in greater access to and control over land for women. Although land can be titled individually in a woman’s name or jointly in the name of both spouses, most land is held by men and a small percentage of land is owned jointly by married couples. There are many constraints that continue to undermine women’s access to and control over land. These include traditional norms and practices that hinder women’s decision-making rights over land, large-scale land acquisition, insufficient access to legal protection, and obstacles to land administration processes in both rural and urban areas to provide secure tenure.

At the same time, the legal framework and policy statements are increasingly targeted to promote women’s access, with policy proclamations to establish quotas for proportion of all applications for land that must be provided to women. Donors should support initiatives that bring a gender focus to the legislative framework and help create the legal space to protect and improve the land rights of women, promote on-going awareness raising programs to inform women, communities, community leaders, traditional leaders of the land rights of women, and ensure all new land-related policies and processes that affirm non-discrimination, equity, transparency and participation. For example, mechanisms to increase access to dispute resolution services, especially by women, should be put in place taking into account the location, language and procedures to increase access by the average woman. A focus on ensuring that implementation matches policy pronouncements is necessary.

As the demand for land increases in Zambia around major cities and district centers alike, commercial and residential interests are expanding into Zambia’s customary land areas. Given the relatively weak rights of compensation or recourse for smallholders on customary land, these populations are being pushed off of prime real estate and are reallocated land further from markets. In these peri-urban fringes there is lack a constructive dialogue between the local councils, who demand land from traditional leaders, and customary authorities, who often see limited benefit for themselves or their subjects alienating land. Investors often reach these areas before local councils are able to register their interests and as a result, there is a lack of planned development as municipalities grow. Donors should promote increased communication and tools for joint planning between planning departments and customary authorities in these peri-urban fringes to protect the rights of existing communities, but also promote service delivery and sustainable growth of towns and cities.

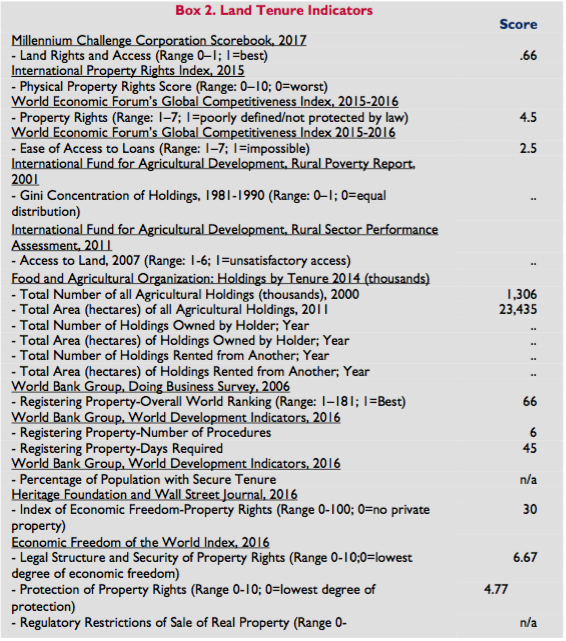

Though restricted to state land, the National Land Titling Program (NLTP) and associated programs (Land Audit, Zambia Integrated Land Management and Information System (ZILMIS), National Spatial Data Infrastructure) are designed to increase revenue by documenting available state land to be brought under leasehold title, and create an inventory of Zambia’s existing leaseholds. There is a need to streamline processing of leaseholds and improve revenue collection and data management systems. Donors should support efforts to manage land information related to leasehold property in order to promote revenue collection and support public service delivery.

Zambia’s long-term development planning strategy, Vision 2030, identifies agriculture, energy, mining and forestry as key economic sectors. Over the past decade, Zambia has seen a sharp rise in foreign and domestic investments in these sectors, generally requiring tracts of land in order to develop the resources under them. While these investments can lead to the development of the economy, bolster sources of capital, contribute to local employment creation, private wealth generation and accompanying development in infrastructure, they can also diminish socioeconomic rights, including land and livelihood protection and protecting the environment if not done appropriately. Donors should ensure that support for land-based investments are also measured against potential contributions to broader development goals such as poverty eradication, green growth, food security and nutrition, mitigation of and adaptation to climate change and sustainable land use. For example, donors can apply a wide variety of international regulatory and voluntary standards on sustainability when developing programs and interventions.

Investment in Zambia’s agriculture is critical to increasing GDP, food security, and access to livelihoods. In attracting more land-based investments for agriculture, however, communities occupying land in customary areas are increasingly being displaced from their lands in the wake of large scale land acquisitions. Customary and state authorities (both national and district) have limited coordination in land management issues, which leads to overlapping allocations of land and resources and accusations of corruption, fueling distrust. Donors should support initiatives that increase tenure security in customary land, promote equitable land allocation and alienation procedures, and support for small farmers, particularly around promoting dialogue and joint planning between customary and state authorities. For example, providing assistance that addresses current constraints in customary land administration processes, including lack of necessary skills and competencies by traditional leaders to manage customary land can help to mitigate displacement, socio-economic exclusion, land conflicts, tenure insecurity, enclosures of common pool resources, and provide a well balanced approach to governing LSLIs in customary settings. Additionally, donors can support the development of civil society mechanisms, such as village land committees and institutions to support customary leadership in land allocation, which have mandates to preside over all land related matters in order to have representation in decision making regarding allocation of large parcels of land.

The benefits of Zambia’s rich forest resources include the provision of products and services, such as timber, raw materials, fuel, food and medicine that contribute to the livelihoods and income of rural communities. They also provide environmental regulating services, such as carbon storage and sequestration, the regulation of water flows and water quality, erosion control, sediment retention, pollination and disease regulation. They also provide supporting services for tourism, recreational activities and other cultural pursuits. Most of Zambia’s forests lie on customary land, yet historically all management rights have rested with the Forest Department. As a result, traditional authorities and neighboring communities have few incentives to support enforcement of forest laws or to keep land forested. The new Forest Act provides opportunities for registration of community rights through community forest mechanisms, which need to be piloted and scaled. Similarly, there are opportunities to pilot community rights devolution processes through other natural resource management legislation. Donors can support efforts to strengthen local forestry management institutions in customary areas in order to mitigate the drivers of unsustainable timber harvesting and wood fuel production, as well as leverage the potential for REDD+ in Zambia to encourage sustainable local forest management by local users.

Summary

Despite a decade of economic growth, 30 percent of Zambia’s population lives on less than $1.90 per day and 60 percent live below the poverty line. Agricultural productivity is low Zambia for a wide range of reasons including drought and flooding, poor access to farming inputs, credit markets, transportation and communication infrastructure, land tenure and larger policy constraints. There has been has a high rate of migration from rural to urban areas and urbanization is on the rise: 40 percent of the population now lives in urban areas and the cities are overcrowded. Most of the country’s urban population lives in unplanned settlements with substandard housing and limited service (World Bank 2017 2011 statistics; GRZ 2013 and CIA 2015; KPMG 2016).

In the mid-1990’s Zambia enacted legislation intended to encourage investment in rural land and improve agricultural productivity through the introduction of state leasehold on customary land. The 1995 Lands Act permitted conversion of customary land into long term leases managed through the Ministry of Lands. In the decade following the adoption of the Lands Act, foreign investors, politicians, and local elites obtained leaseholds. Some large agribusiness, industrial, and tourism investments provided local communities with benefits including employment, outgrower schemes, small-business opportunities, and infrastructure development. In other cases, the conversion of customary land rendered whole communities landless, eroded rights to common pool resources, and enclosed communal land. The Land Tribunal, which was intended to protect and enforce land rights, was underfunded and inaccessible to most of the population, leaving limited options for addressing land grievances.

In the mid-1990’s Zambia enacted legislation intended to encourage investment in rural land and improve agricultural productivity through the introduction of state leasehold on customary land. The 1995 Lands Act permitted conversion of customary land into long term leases managed through the Ministry of Lands. In the decade following the adoption of the Lands Act, foreign investors, politicians, and local elites obtained leaseholds. Some large agribusiness, industrial, and tourism investments provided local communities with benefits including employment, outgrower schemes, small-business opportunities, and infrastructure development. In other cases, the conversion of customary land rendered whole communities landless, eroded rights to common pool resources, and enclosed communal land. The Land Tribunal, which was intended to protect and enforce land rights, was underfunded and inaccessible to most of the population, leaving limited options for addressing land grievances.

In 2006, Zambia’s National Constitutional Convention began in drafting a new Constitution, which continues to support and encourage investment in rural areas while also recognizing weaknesses in the operation of the current legal framework for land, including imbalances in the alienation of land and the need for security of customary land tenure. The 2016 Constitution calls for new and revised legislation governing land rights and supporting principles of land tenure security and equitable access to land and resources (GRZ 2016).

Land areas with high population densities, districts that follow the major road infrastructure north from the capital Lusaka, including the Copperbelt Province, and near urban areas have been subjected to increasing land fragmentation. More that 95 percent of farming households cultivate on five hectares of land or less. In the wake of conversion of customary lands women and smallholder farmers are increasingly vulnerable to tenure insecurity. Among Zambia’s increasingly urbanized population, the proliferation of unplanned settlements has increased tenure insecurity as well as strained the ability of the country’s institutions to provide critical infrastructure such as water and sanitation. Land use conflicts as a result of these dynamics in rural, urban and peri-urban settings are increasing.

Zambia possesses rich natural resources. Zambia is one of the most forested countries in sub-Saharan Africa, and forest land and forest products provide a critical safety net for a wide swath of the country’s impoverished population. Although Zambia is losing forest land to agriculture and to feed the population’s dependence on fuel wood, it is a participant in the United Nations Collaborative Programme on Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation in Developing Countries (UN-REDD) and is currently at the first stage of under the UN-REDD Quick Start initiative. It is also one of the first countries to develop a program through the BioCarbon Fund. The development of minerals resources— particularly copper and cobalt—has historically driven Zambia’s economic growth, leading to infrastructure development and providing employment. The Government of Zambia (GRZ) recognizes the need to diversify the sector to develop other mineral resources, enforce environmental standards, and provide support for small-scale mining enterprises.

Land

LAND USE

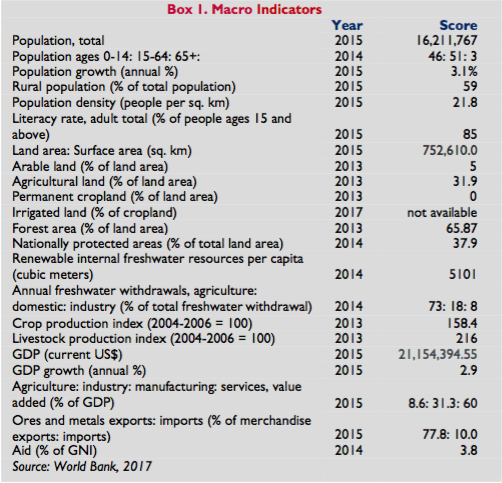

The most recent official population statistic show Zambia has a 2008 population of slightly over 16 million with 59 percent living in rural areas. Zambia’s 2015 GDP is 21 billion, with agriculture comprising 8.6 percent of GDP, industry at 31.3 percent and services at 60 percent. Sixty-five percent of the population is poor and 42 percent is considered extremely poor. As of 2015 the prevalence of HIV/AIDS among adults is 14.3 percent. The number of HIV (AIDS) orphans is estimated at 1.5 million, which means that one in five children in the country is an orphan. In both rural and urban households, poverty levels are highest among female-headed households with extreme poverty levels of more than 60 percent in rural areas and 15 percent in urban areas (World Food Program 2015; World Bank2017).

Most Zambians are subsistence farmers. However, Zambian agriculture has three broad categories of farmers: small-scale, medium and large-scale. Small-scale farmers are generally subsistence producers of staple foods with occasional marketable surplus including, including maize, sorghum, rice, millet and cassava. Medium-scale farmers produce maize and a few other cash crops for the market. Large-scale farmers produce various crops for the local and export markets including tobacco (98 percent of which is exported), cotton, tea and coffee. Thirty-two percent of Zambia’s total land is agricultural. Arable land (hectares) in Zambia was last measured at 3,400,000 in 2011 and about 4 percent of this area as of 2012 (156,000 ha) was under irrigation (The New Agriculturalist, 2013; GRZ 2012; World Bank 2013; CIA 2016; Trading Economics 2016).

Zambia is one of the most forested countries in Africa. About 59 percent of total land is classified as forest area. Deforestation rates vary, however the most commonly quoted figure is 250,000–300,000 ha per year (or approx. 0.50–0.60 percent of total forest cover). Although rich in carbon stocks (above- and below-ground carbon stored in biomass is estimated to be 2.5 billion tones and a further 204 million tons stored in dead wood), Zambia has been identified as one of the top 10 greenhouse gas (GHG) emitting countries as a result of deforestation and degradation. Forest land has degenerated as a result of encroachment from agriculture, tree harvesting for fuel wood and sale, and uncontrolled burning. Overgrazing has resulted in bush encroachment and severe soil degradation. In areas dominated by commercial agriculture, the use of heavy machinery and large amounts of fertilizer and chemicals has degraded the soil (The Redd Desk 2013; FAO 2011; The New Agriculturalist 2013).

Zambia is in possession of some of the world’s highest-grade copper deposits. In 2017, Zambia was the world’s seventh largest copper producer with 74,000 million tons equating. Zambia also produces nearly 20 percent of the world’s emeralds and is among world’s top three emerald producers. Land use issues relating to mining relate to contested ownership of tracts of land for mining development, inadequacy of compensation for villagers, illegal displacement and overall threats to customary land rights (Investing News Network 2017;CoKPMG 2013; Think Africa Press 2013).

Zambia is one of the most urbanized countries in Africa south of the Sahara. It is estimated that 40–48 percent of the population of over 16 million live in urban areas. The population of the Lusaka, for example, Zambia’s capital city, has grown from about 250,000 people in 1964 to about 2.2 million in 2013, representing about 15 percent of the national population. Much of its urban expansion is unplanned and poses challenges in terms of basic urban infrastructure and service provision. The fact that these settlements were not planned has led to them not being considered for local authority services. It is estimated that more than 70 percent of the urban population of the cities live in informal settlements (Tembo 2014; UN Habitat 2014).

LAND DISTRIBUTION

Many statistics and land policy documents assert that approximately 94 percent of Zambia’s land is customary land. The definition of customary areas and state land come from the Lands Act of 1995, which in turn is based on the status of land at the time of independence. In practice, however, land that has been converted to state leasehold tenure within customary areas often loses its relationship to the traditional authorities. Other exclusive state uses are present on customary land, for example National Parks. Game management areas also often have restriction on use by smallholders. Thus, the amount of land that is available to smallholder farmers under customary tenure, and is likely closer to 54 percent of the country, or approximately 40 million hectares of land (Sitko et al. 2015; Sitko and Jayne 2014).

Areas with high population densities, districts that follow the major road infrastructure north from the capital Lusaka, including the Copperbelt Province, and near urban areas have been subjected to increasing land fragmentation. More that 95 percent of farming households cultivate on five hectares of land or less. Farm households cultivating between 10 and 20 hectares have increased by 103.1 percent between 2001 and 2011. These “emergent farmers” are overwhelmingly concentrated in districts that are in close proximity to the “line of rail” and the urban mining areas of the Copperbelt. Farms controlling between 5 and 100 hectares now account for more land than the entire small-scale farm sector. Eighty-eight percent of the most productive agricultural land (most of which is located in the fertile eastern-central region of the country) is devoted to cash crops, including cotton, tobacco, and flowers (Government of Zambia 2002; Zambian Development Agency 2014; Zambian House of Chiefs 2009; Central Statistical Office, 2011; Sitko and Jayne 2014).

Since enactment of the 1995 Land Act, which allowed for conversion of customary tenure to state leasehold tenure, based on data collected by the Ministry of Lands, a total of 5,098 land conversions have been recorded between 1995 and 2012. This amounts to approximately 280,000 hectares of customary land that is now administered through leasehold title by individuals for agricultural purposes or an average of 54 ha per transaction. The scale of customary land conversion for agricultural purposes amounts to 12 percent of the total area cultivated in 2012 by smallholder farmers. These conversions are heavily concentrated in the areas close to urban areas with relatively good access to markets. For example, 73 percent of registered new land acquisitions have been occurring in the relatively urbanized provinces of Lusaka, Central, and Copperbelt. These figures may be somewhat underestimated given costs and inconvenience of fully registering leasehold applications in Lusaka. In some cases, the conversion of customary land to large leaseholds has eroded local rights to common-pool resources, and enclosed communal land. As land is acquired for commercial farming, industry, and tourism, local people in some areas have lost access to water sources, grazing land, and forest products. In other cases, protected areas have been identified for development (Chapoto et al. 2013; Brown 2005; Black Lechwe 2006).

Zambia is rapidly urbanizing. The country’s urban population is unevenly distributed: Two provinces, Copperbelt and Lusaka, account for 69 percent of the total urban population. The country has eight major cities—Lusaka, Kitwe, Ndola, Mufulira, Chingola, Kabwe, Livingstone and Kapiri Mposhi, Chipata and Solwezi with populations in excess of 150,000; most of these are in the Copperbelt province. Provincial headquarters, such as Kasama, Mongu, Chipata and Mansa are large urban centers that are growing, particularly alongside decentralization (UN Habitat 2013).

LEGAL FRAMEWORK

In 1924, control of all land in present day Zambia was transferred from the British South African Company to the Governor of Northern Rhodesia, under the Northern Rhodesia Order in Council of 1924, with the exception of Barotseland (present-day Western Province, which still operates under its own unique customary land management system). Two subsequent Orders in Council, the Northern Rhodesia (Crown Land & Native Reserve) Order in Council 1928, and the Northern Rhodesia (Native Trust Land) Order in Council 1947, became the Zambia State Land and Reserve Order 1963 and the Zambia Trust Land Order 1964. These orders established state and customary land types, converting Crown Land to State Land and Native Reserve Land and Native Trust Land to Reserve Land and Trust Land under customary management. The first law that allowed for compulsory acquisition of land in the public interest was passed in 1969, and in 1970 Barotse Land (Western Province) was integrated into Zambia as Reserve Land. In 1975, Zambia dramatically reformed land ownership with the Land (Conversion of Titles) Act, which abolished freehold tenure in Zambia and converted freehold property into 100-year leaseholds. The Act also abolished leaseholds of greater than 100 years. This act banned the sale of undeveloped (bare) land. This prohibition is still in force and makes sale of customary land as illegal.

Current land administration procedures were established in the Land Circular of 1985, which established a principal/agent relationship, with the Commissioner of Lands as the Principal and local and provincial councils as local agents for decentralization. This circular also defines how to apply for leases, and the administrative processes for land converstion. Since 1985, and based on the Land (Conversion of Titles) (Amendment) Act, land may be allocated to non-Zambians though there are conditions for foreigners to own land.

The 1995 Act vests all land in the President for and on behalf of all the Zambian people. It articulates land administration under two tenure systems: statutory and customary tenure. The Act recognizes and allows for the continuation of customary tenure. However, customary tenure can be converted into private leasehold tenure, but once converted, customary land rights are extinguished and the land cannot be converted back to customary tenure. Statutory land is administered in accordance with written laws and by government officials. Customary land is administered by traditional authorities based on localized customary laws, which are often unwritten. The effects of the implementation of the Land Act have been debated, but observers assert that the primary impacts include that 1. Any entity (local or foreign) can acquire land, by negotiating with a chief and with local government endorsement; 2. Domestic and foreign investors can acquire land for commercial farming, superseding the land rights of the local population; 3. Land is being increasingly commoditized; and 4. Traditional leaders are tasked with administering land on behalf of their people, often to pecuniary ends (GRZ 1995a; Mushinge and Mwnado, 2016; Mushini and Mulenga 2016). It is important to note that although the above criticisms are often leveled at the institution of the chief, however, it is important to note that Chiefs have little or no guidance or training on appropriate procedures for customary or state land allocation; 2. The law requires that consultation with affected communities occurs; and 3. It is the responsibility of both the Chiefs and Local Councils in signing off on applications to convert customary to leasehold tenure to ensure that the conversion does not infringe on any other rights (including those of local communities).

Zambia’s new Constitution of 2016, which amends the Constitution of Zambia Act 1991, dedicates a section to Land, Environment and Natural Resources. It specifies the principles of land policy, environmental and natural resources management, provides the protection of natural resources and restricts their utilization and establishment of a Land Commission: “to administer, manage and alienate land, on behalf of the President” The Constitution provides for: (1) equitable access to land and associated resources; (2) security of tenure for lawful land holders (3) recognition of indigenous cultural rites; (4) sustainable use of land; (5) transparent and cost-effective management of land; (6) conservation and protection of ecologically sensitive areas; and (7) cost-effective and efficient settlement of land disputes; and (8) river frontages, islands, lakeshores and ecologically and culturally sensitive areas be accessible to the public; not to be leased, fenced or sold; and maintained and used for conservation and preservation activities; (9) investments in land must also benefit local communities and their economy; and plans for land use to be done in a consultative and participatory manner. The constitution confirms the equal worth of women and their rights (Preamble). In addition, Article 118 specifies that traditional dispute resolution mechanisms shall not contravene the Bill of Rights or be inconsistent with the constitution or other written law (GRZ 2016; Zambia Weekly, 2017; GRZ 1995a). The Constitution development process was a controversial period, particularly as traditional leaders had concerns with the vestment of land in the Office of the President.

Urban land related legislation includes the Urban and Regional Planning (URP) Act of 2015. This Act provides a framework for administering and managing urban and regional planning in Zambia by providing for development, planning and administration principles, standards and requirements for urban and regional planning processes and systems. The Law establishes a democratic, accountable, transparent, participatory and inclusive process for urban and regional planning that allows broad based participation of; communities, private sector, interest groups and other stakeholders in the planning, implementation and operation of human settlement development. This Act also guarantees sustainable urban and rural development by promoting environmental, social and economic sustainability in development initiatives and controls at all levels of urban and regional planning (GRZ 2015b). In planned areas, the URP enables local authorities to issue “Occupancy Licenses” for 30 years. While these licenses allow the holder to apply for a Certificate of Title, common experience has been that households have been satisfied with the security of tenure offered by Occupancy. The act allows for planning to occur within customary areas, preferably with the agreement of traditional leaders. It allows for traditional leaders to be overridden however by the Minister of Lands or the President. The act also envisions a decentralized planning system that places powers in the District Planning offices. The enactment of the URP repealed the Town and Country Planning Act of 1962 and the Housing (Statutory Improvement Areas) Act of 1974. While the goals of the URP include expanding planning, simplifying procedures and rules and encouraging public participation, as of 2017 the associated regulations for implementing the Act have not been approved, nor have District Planning offices gained capacity to take on the added responsibilities associated with implementation.

TENURE TYPES

Under the 1995 Land Act and Constitution, all land in Zambia vests in the President. Land tenure types are:

Customary tenure. The majority of land in Zambia is held under customary tenure. Under customary law, individuals, families, clans, or communities hold land from generation to generation, without temporal limitation. Customary tenure applies to individual plots, forest land, common land within a village, and communal grazing land. Most smallholder subsistence farmers cultivate customary land that may or may not be held in common ownership with the community/family, although the rights of farmers are individualized. The land often does not have formal documentation (e.g., certificates, titles) and the landholders do not pay land tax. A caveat to this can be found in the Western Province, where the traditional land administration system of Western Province is well organized and decentralized. It has a clearly defined process with responsible officials accountable at each level and issues land ownership certificates (LOCs) that are locally binding, and have been used in the courts, but are not formally recognized or registered with the central government. Nonetheless those who have LOC’s, according to research, perceive that they have security of tenure and that traditional land administration practices collectively provide a de facto security of tenure (Mushinge and Mulenga 2016; Jayne et al. 2016). Recent evidence suggests that customary documentation is more prevalent than previously understood. Data from the Rural Agricultural Livelihoods Survey indicate that 6 percent of households in over 30 percent of chiefdoms indicated having some form of documentation to their right to land. Some of these represent farm permits or village land registers and none are known to be spatially explicit.

Leaseholds of state land. All land not defined as customary areas is deemed to be state land. The state grants four types of leases: (1) a 10-year Land Record Card; (2) a 14-year lease for un- surveyed land; (3) a 25- to 30-year Land Occupancy License for residential settlements (issued by Local Government under the URP); and (4) a 99-year leasehold for surveyed land. The conversion of customary tenure to leaseholds must take into consideration local customary laws on land tenure and with the approval of Chiefs, district Councils, and any person whose interests might be affected by the conversion, though in practice this consideration may not always occur. The 1995 Land act also allows “any person” who holds land under customary tenure to apply to convert it to a leasehold title for a period not to exceed 99 years. Due to the high costs associated obtaining leasehold titles, the conversion process puts impoverished villagers at a disadvantage compared to those with titles. Titles are registered in Lusaka and there are very few land services at the provincial level. As a result, there is some evidence that many landholders in distant areas choose not to register for title in Lusaka or only partly complete the conversion process. Additionally, although the Land Act provides villagers with an opportunity to use their land as collateral to secure credit, the costs are also prohibitively expensive for many villagers (GRZ 1995a; ZLA 2008; Tagliarino 2014).

Leaseholds of state land. All land not defined as customary areas is deemed to be state land. The state grants four types of leases: (1) a 10-year Land Record Card; (2) a 14-year lease for un- surveyed land; (3) a 25- to 30-year Land Occupancy License for residential settlements (issued by Local Government under the URP); and (4) a 99-year leasehold for surveyed land. The conversion of customary tenure to leaseholds must take into consideration local customary laws on land tenure and with the approval of Chiefs, district Councils, and any person whose interests might be affected by the conversion, though in practice this consideration may not always occur. The 1995 Land act also allows “any person” who holds land under customary tenure to apply to convert it to a leasehold title for a period not to exceed 99 years. Due to the high costs associated obtaining leasehold titles, the conversion process puts impoverished villagers at a disadvantage compared to those with titles. Titles are registered in Lusaka and there are very few land services at the provincial level. As a result, there is some evidence that many landholders in distant areas choose not to register for title in Lusaka or only partly complete the conversion process. Additionally, although the Land Act provides villagers with an opportunity to use their land as collateral to secure credit, the costs are also prohibitively expensive for many villagers (GRZ 1995a; ZLA 2008; Tagliarino 2014).

Squatting. In Zambia about 70 percent of urban dwellers live in informal settlements. These informal settlements are characterized by unsafe physical environments, such as unstable hillsides or flood plains, without the benefit of legal and political rights. In areas where settlements are built on primarily public land that have local area plans and the structures meet building standards, residents can regularize their rights with 30-year renewable Land Occupancy licenses. In other informal settlements, residents do not have rights to their residential land under formal law. Customary law often recognizes occupancy rights of residents, which may protect their interests against other potential occupants but offers limited protection from eviction by government officials (Kawanga 2014; LCC 2008).

SECURING LAND RIGHTS

Land is obtained through the following methods in Zambia:

Inheritance. Zambia’s customary land has historically been kept in the lineage or clan; in patrilineal communities (prevalent throughout parts of Zambia) land is passed to male lineage or clan members. Typically, a male member will receive a portion of a lineage- or clan-holding simply by virtue of his membership in the lineage or clan. In the matrilineal communities found in the northern and eastern parts of the country, land is passed through the female line. As customary land has become more individualized, the nuclear family has grown in importance, and in many areas land is passed down through the nuclear family as opposed to a lineage or clan. The Intestate Succession Act deals specifically with property such as land, housing, money in bank accounts. This law indicates that upon death, 50 percent of the property will be inherited by the deceased’s children (equally shared among all children), 20 percent by the surviving spouse (or divided among the legal spouses in case of a polygamous marriage), 20 percent by the deceased’s parents (equally shared among both living parents) and 10 by any other deceased’s dependents (Unruh et al. 2005; GRZ GIDD 2005; Habitat for Humanity 2017).

Land allocation. The chief or headman allocates customary land and the process depends on the origin of the applicant. Families that have been residents in an area can allocate forest land for agricultural expansion to other family members with little or no interaction with headpersons or the chief. However, if individuals are settling from outside of the chiefdom, they must pass through the Chief’s office with a letter of recommendation or transfer from their previous chiefdom. Women usually access land through their families. In areas where land is scarce, the local leadership may divide existing plots. Local leaders may allocate land to a single woman for farming, especially if she has children. The new landholder will clear the allotted land to confirm his rights. In some circumstances customary land rights may be enhanced by way of customary landholder certificates and other customary titles with current estimates that 6% of customary landholders have some form of land documentation (Unruh et al. 2005; 1998; GRZ GIDD 2005; Brown 2015).

Lease. Individuals and entities can acquire transferable leasehold rights to land by converting their customary landholdings or approaching local authorities to identify state land available for lease, or customary land that a landholder is interested in converting to leasehold land. The 1995 Land Act requires the authorization of the chief and consent of any other person affected by the land lease for a land conversion. Local authorities apply for leases through the Commissioner of Lands, who is authorized to grant leaseholds on behalf of the President. Surveys are required for 99-year leases. The state can grant a 14-year lease based on submission of a sketch of the land, and the 14-year lease can be converted into a 99-year lease when a survey is completed (GRZ 1995a). As of 2003, there were an estimated 2,000 to 4,000 applications for conversion of land from customary tenure to statutory leasehold being received by the Ministry of Lands each year, with several years’ backlog of applications (Adams 2003).

There has been an increase in rural leaseholds obtained by large commercial and medium-scale farmers, politicians, and local elites, particularly in the peri-urban peripheries of towns and cities. Chu et al. (2015), through case study methodology, estimate over 300,000 hectares of customary lands have been converted for large-scale initiatives, but exact data is not available. In terms of conversion of individual lands for conversion, most poor, small scale and subsistence farmers do not convert their land to leasehold due to costs, low levels of awareness of land rights, and inability to secure access to credit markets, as was the intention of the Land Act. There has also been some reluctance on the part of traditional leaders to sign off on requests for land conversion from existing community members for fear of losing influence over their subjects. In the process of conversion of customary land for example to a larger agricultural enterprise, the chief has no authority to sign the conveyance as one of the parties to a contract. The lease contract is only signed between the Commissioner of Lands (on behalf of the President) as a lessor and the investor as the lease. In order to provide checks and balances, the chief’s recommendations are included in the process. However, there are some lapses and delays in paper work at the District Councils offices or in the Commissioner of Lands offices. This creates a loophole for corruption as the investors move quickly to develop the land (Chu et al. 2015; Mushinge and Mwanda 2016; Mwiche 2016). There is a tendency for domestic investors to complete paperwork for conversion at the local level (with chiefs and local council), but not to apply for a certificate of title at the Ministry of Lands. Reasons for this may include a cumbersome process and the fact that once registered, investors would need to pay ground rent.

Zambia is among the most rapidly urbanizing countries in Africa. This comes with a number of challenges, including rising cost of land, inaccessibility to land, uncontrolled and unguided land use and degradation, illegal conversion of land use, insecure tenure, and land shortages in some places. Customary land rights on the urban fringe are increasingly becoming ambiguous due to intrusion by rapidly approaching city developments. Peri-urban land is privately being sold to developers by some traditional authorities, often without the knowledge or benefit of the residents. In urban areas, applicants for land can apply to the Planning Authority, the Commissioner of Lands, or directly to entities that construct houses. Prices are high, and there is no assurance of services. In order to transfer and register leased land in urban and peri-urban areas, the parties must engage a lawyer to obtain a non-encumbrance certificate and draft the purchase and sale agreement. The seller of the property must apply for the state’s consent to the sale, obtain a tax form from the Zambian Revenue Authority, and pay the property transfer tax. Once payment is verified, the purchaser can lodge the assignment for registration at the Land and Deeds Registry (Sitko 2010; Sitko et al. 2014).

Landholdings in informal urban settlements are insecure. The land is subject to acquisition for planned urban development. In order to obtain a leasehold interest in an informal settlement on state land, the settlement must be “declared” by the Ministry of Local Government and Housing. The Ministry will only “declare” a settlement under certain circumstances, requiring evidence that 60 percent or more of the land is publicly owned and 50 percent or more of the dwelling structures are built of standard materials. Few settlements qualify, but if one does the city council can issue renewable 30-year occupancy rights to residents (Lusaka Times 2014: LCC 2008; UN-Habitat 2009; GRZ 2015).

Special circumstances. Article 3 of the 1995 Land Act provides that in (undefined) special circumstances the President can make land grants for periods exceeding 99 years (GRZ 1995a).

INTRA-HOUSEHOLD RIGHTS TO LAND AND GENDER DIFFERENCES

Both law and custom govern women’s land rights in Zambia. Formal law, such as the Constitution and the Lands Act, support women’s property rights and prohibit gender-based discrimination. Government has established a target of 50 percent of all land allocations to be reserved for women. The 2016 Constitution confirms the equal worth of women and their rights (Preamble) and sets statutory law above customary law (see below). In addition, it directs that the electoral system must ensure gender equity in parliament and councils (Article 45), and provides for a Gender Equity and Equality Commission to be established. Any individual has the legal right to apply for land and a title deed and by law and land can be titled individually in a woman’s name or jointly in the name of both spouses. In urban areas, educated single women and some married women often buy plots in their own names. The Intestate Succession Act of 1989 recognizes women’s rights to inheritance whether married under statutory or customary laws. Widows have the right to inherit 20 percent of their husbands’ property, while 50 percent of the estate goes to the children of the deceased (irrespective of gender), 20 percent to the parents of the deceased, and 10 percent to other marriages (GRZ 1995; GRZ 2016; OECD 2014).

Customary rules and practices may discriminate against women when it comes to access and control over land. Married women in patrilineal communities access land through their husbands. In matrilineal societies, women access land through their natal families and men receive land through their wives. The male head of household usually exercises primary control over the land. If the relationship terminates by divorce or death, women are often denied continued use of the land in patrilocal systems. A chief may allocate land to a single woman for farming, especially if she has children. Household documentation data from Eastern Province, showed that 78% of parcels on customary land (out of over 6,000) had women as either the sole landholder or a joint landholder. Female chiefs or headwomen do not necessarily act differently from their male counterparts in administering land, and most rural women do not challenge their unequal positions under customary law (Veit 2017; Machira et al. 2011).

Barriers to women’s land ownership, access and control of land relate to the following:

- Acquisition of traditional land by foreign investors is leading to displacements of people from their land.

- Lack of awareness unaware of the rights and the policies put in place by government to protect them.

- Inability to access bank loans to purchase or invest in land.

- Insufficient legal protection of customary tenure e.g. lack of proper documentation.

- On the face of it statutory laws do not directly discriminate against women but in application gender considerations are important. The high poverty levels among women mean they have fewer resources to acquire title deeds; a process that is long, tedious and expensive. Subsequently they face difficulties to meet payments such as ground rent, rates etc. that are necessary to maintain ownership of the land.

- Inadequate information on the land ownership, boundaries and sex—disaggregated data.

- Even when women have acquired land inadequate resources to develop it within the stipulated period leads to dispossession by authorities or to decisions by women to sell off land after acquiring it (Zambia Land Alliance 2015, Veit 2017).

In terms of policy provisions, the revised National Gender Policy (NGP) provides for 50 percent of all land available (state or customary) to be allocated to women and the remaining 50 percent to be competed for by both men and women. While, this is being achieved in some districts (such as Chipata), a lack of statistics means it is difficult to see if these targets are being achieved, though they are  collected and kept at district level. Anecdotally the cost, bureaucracy, and time required to acquire title deeds mean that it is unlikely that the poorest women, particularly those living outside of Lusaka are able to acquire a title deed. The Strategic Plan 2014-2016 for the Ministry of Gender and Child Development (MGCD), although not mentioning land issues specifically, does contain provision for better implementation of the National Gender Policy (GRZ 2014b).

collected and kept at district level. Anecdotally the cost, bureaucracy, and time required to acquire title deeds mean that it is unlikely that the poorest women, particularly those living outside of Lusaka are able to acquire a title deed. The Strategic Plan 2014-2016 for the Ministry of Gender and Child Development (MGCD), although not mentioning land issues specifically, does contain provision for better implementation of the National Gender Policy (GRZ 2014b).

LAND ADMINISTRATION AND INSTITUTIONS

The Ministry of Lands is the principle ministry responsible for land administration and management and includes the Lands Department, Lands and Deeds Department, Lands Tribunal, Survey Department, and Survey Control Board. Zambia’s 108 district councils have authority to administer land within their districts and have responsibility for land-use planning, in coordination with the Urban and Regional Planning Departments. The district councils process applications for leases of state land and evaluate requests for the conversion of customary land to state land. At the central level, the Commissioner of Lands within the Ministry of Lands exercises authority on behalf of the President. Only Copperbelt Province has a provincial office responsible for land administration; the rest of the country must conduct transactions in Lusaka. The Lands Act also established the Lands Tribunal for settlement of land disputes that arise in order to give the public a fast-track method of resolving land disputes that is efficient and cost-effective compared to the established judicial or court system. The Tribunal is a circuit court and can sit at any place in Zambia where there is a dispute. In practice though, the Tribunal deals primarily with disputes over leaseholds (Brown 2005; Adams and Palmer 2007; Mwichi 2016).

Chiefs and headmen on behalf of their tribal communities administer customary lands. Zambia has 73 tribes and 288 Chiefs. On customary land, titles typically do not exist, land taxes are not paid (though there are customary contributions made), and transfer and use are governed by customary law. The chiefs and village-level headmen have authority under formal and customary law to oversee customary land and protect their community’s culture and welfare. The traditional leaders grant occupancy and use-rights, oversee transfers of land, regulate common-pool resources (opening and closing grazing areas, cutting of thatch), and adjudicate land disputes. Although the traditional rulers and traditional systems are legally recognized in Zambia, there exists a limit in their role as managers of land under customary tenure in part because they rarely have responsibilities over the natural resources on the land. For example, when an investor acquires a parcel of customary land, formal involvement in land administration ends at approving that particular land can be converted to leasehold (Mwiche 2016).

Customary lands are not registered with the government and the owners of these plots of land do not hold title or typically any documentation as proof of ownership, outside of farm permits and notations in village registers. These lands are largely regulated outside the statutory and official realm of the Zambian government, though traditional leaders may document rights within their chiefdoms. To fill this void, administration of customary tenure rights to improve tenure security have included initiatives to distribute Traditional Land Holding Certificates (TLHC). TLHCs vary in their design, but often carry the name of the landowner, the relevant headperson, and the area chief’s signature and official stamp; some also have a field or property site plan attached and details of conditions under which the TLHC will operate. In some cases, local courts have recognized TLHCs as evidence of ownership. Zambia is also planning to implement National Titling Programme, which will be spearheaded by the Surveyor General’s office. Some of the innovations envisaged include the introduction of para-surveyors, since there are only 35 registered surveyors in Zambia currently. The National Land Titling (NLTP), which is scheduled for implementation in 2017 may not include traditional or customary land (Mwulenga and Miti 2016; Pritchet et al. 2016; Lusaka Times 2016).

LAND MARKETS AND INVESTMENTS

In urban areas of Zambia, formal plots are scarce and prices are high. In Lusaka for example, available evidence suggests that more than 70 percent of the city’s urban population reside on 10.5 percent of the land in unplanned and informal settlements. Many of these informal settlements have been formalized where residents were allowed to obtain an occupancy license, which is renewable after 30 years. However recent data indicates that only 12 percent of the residents have managed to obtain certificates of title because they are required to pay regular fees in the form of ground rent, which many cannot afford. Thus, access to land for most people in unplanned settlements has largely remained outside of the formal land market. It is estimated that 60 percent of the land is delivered through informal markets. Even in the formal land market, the land delivery system is inefficient and time consuming, involving long waiting periods at every stage of the process from surveying to the issuing of a title. Land purchasers will adopt other means of accessing land including invasions, informal markets and corruption (Gastorn 2013; Chitonge and Mwfune 2015; Pithouse 2014).

There is no formal land market in the customary tenure sector. Customary land transactions are forbidden by law. Informal leases are permitted only when these do not involve payment of lease fees. Rural land is plentiful in areas that are far from main roads, rivers, and rail lines, and are lacking in mineral resources, or in natural resources that could support tourism development. In more productive areas and areas served by infrastructure, land has become scarce and land speculation is common, especially in peri-urban areas and in the vicinity of significant natural resources. Because agricultural development policy in Zambia is promoting commercialization in both the state and customary tenure categories, competition for land in more accessible regions is raising the value of that land and increases incentives to transfer it to leasehold title per the terms of the Lands Act. While the costs of converting customary land to state land are beyond the resources of the vast majority of Zambia’s farmers, the costs are a fraction of the potential profits, and the market encourages investors and agents with resources. These investors and middlemen often only pay registration and survey costs for communal land that they convert. Even if they pay a “facilitation fee” to chiefs, the costs are small in relation to the potential profits made (Chitonge and Mfune; Sitko et al. 2015; Brown 2005; LCC 2008).

Illegal and clandestine land markets are active on customary land and the land sales in Zambia are now far more common on customary land than on state land. This is because the land speculators are able to navigate through the conversion process where they obtain customary land with intentions of titling it in order to increase its value. While the 1995 Lands Act places the power to convert customary land to leasehold title in the hands of the local traditional authority, it does not provide guidance or mechanisms to protect usufruct rights holders from having their land appropriated or to allow local residents to convert their land to leasehold title. The law protects these rights’ holders, but in practice their rights are frequently ignored and no consultation occurs. Thus, rather than reflecting a process of land alienation by local farmers seeking to secure their land rights under conditions of mounting scarcity, the growth in land titling in more market accessible regions is being driven in large part by non-local urban wage earners (Sitko et al. 2015; Nolte 2014; Sitko 2010).

COMPULSORY ACQUISITION OF PRIVATE PROPERTY RIGHTS BY GOVERNMENT

The Lands Acquisition Act (1970) remains in effect and grants the President the power to compulsorily acquire property of any description when “he is of the opinion that it is desirable or expedient in the interests of the Republic to do so.” Notice is required before the government can enter into any building or enclosed space or require occupants of land to give up possession. Upon acquisition of land, the state may offer the landholder a grant of other land or just compensation, consistent with the Resettlement Policy of 2017. Compensation may be denied for undeveloped land and land held by absentee owners (GRZ 1970). Similarly, there are no provisions for compensation of customary rights’ holders when government acquires customary land, for example to expand district municipality boundaries.

LAND DISPUTES AND CONFLICTS

Thus far, conflict in Zambia has generally been resolved without the resort to violence. Limited information on the nature of land disputes in Zambia is available, but increases in urban land-related conflicts are reported. The types of land conflicts include:

- Concurrent claims on the same plot of land.

- Invasion of previously idle land by non-landowners. Such conflicts are among those leading to violence, especially in Lusaka.

- Community protests arising when the state threatens to demolish the structures that are classified as illegal settlements.

- Boundary disputes between the state and other institutions or rights holders over a piece of land (Chitongo and Mwfune 2015; Lusaka Times 2014; Resnick 2011).

In rural areas land conversions and the establishment of farm blocks for commercial farming are an increasing cause of concern among local farmers and have the potential to create conflict. Disputes between Chiefdoms over boundaries and ownership of pieces of land in high value rural lands are also reported. Conflicts relating to evictions of small holder farmers have occurred in Luapula Province, which borders the mineral-rich Katanga region of the Democratic Republic of Congo, and has deposits of manganese, cobalt, citrine and copper (Sambo et al. 2015; Chooma 2014; IRIN 2010).

The most common method for resolving land disputes is through the local traditional leaders (headmen or chiefs). The customary leadership structure is hierarchical and disputes that cannot be resolved at lower levels can proceed to consideration by senior and paramount chiefs. In resettlement areas, parties can also approach the resettlement-scheme management for dispute resolution. The 2010 Lands Tribunal Act established mobile Land Tribunals, which were intended to be a low-cost, accessible alternative to the formal court system. In practice very few rural Zambians know of the tribunals’ existence. The tribunals have insufficient funding to conduct public awareness campaigns, tend toward formal proceedings conducted in English (which reduces their accessibility), are limited to addressing statutory land cases, and operate with a two-year backlog of cases. Other formal conflict resolution tribunals are the Town and Country Planning tribunal and Magistrate and High Courts. There is little evidence of the use of these forums by the economically disadvantaged (GRZ 2010; Myunda 2012).

CONSULTATION AND CONSENT

Zambia’s 2011 Environmental Management Act (part VII, 91) provides a framework for public participation in environmental and development decision making. It supports the public right to be informed of official decisions that affect the environment, and the right to provide public comments that authorities must respond to. The act does not help define “public” for purposes of participation. Early analysis of ZEMA’s compliance with the Act has demonstrated the challenges faced by the Agency in monitoring and enforcement (Chifungula 2014). Regulations that would clarify how to implement the law have not been developed or widely shared.

While consultation requirements are common in Zambian legislation, there is limited guidance provided about how to conduct a consultation. For example, the Wildlife Act of 2015 requires consultation with the Zambia Wildlife Authority and local communities prior to declaration of National Parks. The 2015 Forest Act calls for management plans to be established in consultation with “holders of rights, title or interest in the Local Forest” and requests submissions from the “local community in the area.” The 1995 Lands Act prohibits conversion of customary land to titled state land without consulting “any person whose interest might be affected.” As a result, over most of the past two decades, however, the ambiguities around consultation means that there is little evidence of the effectiveness of these requirements. There is limited experience with requirements for local communities and rights holders to “approve” or consent to actions that may affect their statutory or customary rights. This may be in part due to the lack of communities having legal status to represent or sign on behalf of a group interest. For example, while the 1995 Lands Act requires broad consultation, approval is only required from the chief and local authority to convert land.

KEY LAND ISSUES AND GOVERNMENT INTERVENTIONS

The Zambian government is in the process of finalizing the 7th National Development Plan 2017–2021 (NDP), which is expected to provide “practical implementation strategies” for the government’s goals to achieve economic transformation through an “integrated approach” that links key sectors. The NDP provides an opportunity to prioritize government objectives toward poverty reduction and strengthening the linkages between budgeting and planning. It is part of the cascading system of planning that commenced with the National Vision 2030 prepared in 2005, and breaks down to rolling annual plans. A Ministry of Planning and National Development has been created to spearhead national development. The Plan acknowledges that the management of a land tenure system, acquisition and general land usage are critical to economic and national development. Due to information gaps, it has been difficult to ascertain total land availability and usage patterns in the country. During the Plan period, a land audit will be undertaken which is expected to improve land administration and increase ground rent revenue collection (GRZ 2013).

Informed by National Vision 2030 and the Constitution, the Land Policy Document through the Ministry of Lands, Natural Resources and Environmental Protection (MLNREP) is envisioned “to provide an efficient and effective land administration system that promotes security of tenure, equitable access and utilization of land for the sustainable development of the people of Zambia.” The National Land Use Policy allows land use planning principles throughout the country in order to accommodate actions to mitigate climate change impacts, sustaining forests, food, water and health benefits to help local communities and to conserve biodiversity and ecosystem services. Crucially, the land policy seeks to adopt a unified approach to land administration and recognizes land rights originating from customary tenure as the same as the leasehold land rights: customary land rights shall henceforth be equal in weight and validity to documented land claims (GRZ 2015c). The Land Policy process was originally started in 2006, but was delayed to accomodate the Constitutional amendment process. The process was relaunched in 2014, using the 2006 draft policy as a starting point. Since 2014, the policy has gone through a number of. Limited consultations were carried out on the draft policy in 2015 and 2016. As a result, there is not a broad awareness of the policy development process. While many chiefs have been open to the concept of documenting customary land holdings, they are also the most vocal critics of the draft policies, seeing efforts by government to develop a unified tenure system as a threat to the institution of chiefs. Chiefs have also rejected the introduction of various levels of land boards into the customary land administration process.

In 2016, along with the prioritization of the completion of the Land Policy and launch of the National Land Titling Program, Zambia prioritized the development of a Customary Land Administration Bill, which would bring some harmonization to customary land administration, while still keeping customary land under the administration of traditional leaders. The bill has not yet been adopted.

In 2013/2014, the Ministry of Lands Launched the Zambia Integrated Land Management and Information System (ZILMIS), designed provide a secure and transparent digital information system for land transactions. ZILMIS should streamline processes and workflows and enhance land records management. The system is designed to work with 10 provincial offices that allow for decentralized use. Since the launch of ZILMIS, and the reported integration of 500,000 land records and millions of sub-records, there has been relatively few updates on its use.

The National Land Audit and National Land Titling Programs are key efforts of the Ministry of Lands that aim to build on the ZILMIS platform. The National Land Audit is based on the recognition that land administration, forestry and environmental management activities have been fragmented and have lacked collaboration and cooperation. As a result, a Land Audit hopes to gather information on land titles, as well as land uses and competition among these land uses with an integrated land-use master plan, updated spatial information across sectors and increased collaboration among sectors. This includes: land inventory; land dispute resolution; national spatial data infrastructure; information dissemination; and land governance.

As of 2014, Zambia only had an estimated 141,625 certificates of title across 750,000 square kilometers. The National Land Titling Program (NLTP) seeks to document titles on state land, which will increase revenues for local councils as well as the Ministry of Lands, while offering increased security of tenure and options for using land as collateral. At present the NLTP is restricted to state land, and is focused on resettlement schemes and regularization of informal settlements. The program’s success will be based on the ability of the country to embark on low-cost surveying methods, availability of financing, and ability to document and subsequently administer land at this a dramatic scale.

The Government of Zambia has embarked on a program to open up viable Farm Blocks in various parts of for primary agriculture production and value added activities. The Farm Block Development project identifies promising land by negotiating with chiefs, converting the customary land to state land, and investing in complementary infrastructure such as feeder roads, electricity, water for irrigation, and communication facilities. The land is demarcated into large plots and offered to investors as long-term leaseholds. In these interventions the government provides basic infrastructure such as roads, bridges, and electrification. In Farm Block design areas of over 10,000 hectares are made available to investors. The Luswishi Farm Block initiative, for example, to be implemented in 2017 by the Ministry of Agriculture seeks to contribute to food and nutrition security, poverty reduction and economic growth through enhanced agricultural production, productivity and processing. The farming blocks are expected to benefit neighboring smallholders with the development of infrastructure, opportunities for secondary businesses, and establishment of new markets (Zambian Development Agency n.d; AFDB 2016) However, consultations associated with the establishment of Farm Blocks may be insufficient, there is less-than-expected interest from investors, and some investments are taking place in areas with existing populations, all of which contribute to concerns around the Farm Block initiative (Sipagule et al. 2016).

DONOR INTERVENTIONS AND INVESTMENTS

DanChurchAid (DCA) partner, Zambia Land Alliance (ZLA), is piloting new ways of securing land rights and ownership for the majority of Zambia’s poor rural households through a project encouraging traditional chiefs to issue Customary Land Holding Certificates. The project called “Enhancing Sustainable Livelihoods for the Poor and Marginalised Households through Land Tenure Security (SULTS), is aimed at empowering the poor and marginalized communities to hold local leaders accountable in administration of customary land. Co-financed by the European Union and DCA, and implemented by ZLA in collaboration with associate partners, Gwembe District Land Alliance (GDLA) and Monze District Land Alliance (MDLA), the project, targeted over 4000 households in the Districts of Gwembe, Monze and Solwezi.

USAID’s 2014–2018 Tenure and Global Climate Change (TGCC) project supports agroforestry extension services and works to increase tenure security. It is being implemented in the Chipata District of Zambia’s Eastern Province. This project explores the relationship between secure resource tenure and goals related to climate change adaptation and mitigation. Its activities are designed to increase tenure security at the chief, village and household levels and support agroforestry extension services (primarily at the village level). TGCC is also supporting the documentation of a rural chiefdom in Petauke District to examine the relevance of the approach to land-use planning in game management areas. The project supports USAID/Zambia development objectives of improved governance, reduced rural poverty through improved agricultural productivity of smallholders, improved natural resource management, and improved resilience.

UN-Habitat has supported the People’s Process on Housing and Poverty in Zambia to apply the Social Tenure Domain Model (STDM) approach to documenting community and household rights in Mungule and Chamuka Chiefdoms in peri-urban areas outside of Lusaka. These efforts have contributed to the Ministry of Lands and Natural Resources design of the National Land Titling Program methodologies and processes, particularly as it relates to the potential for documentation on customary land.

Zambia Governance Foundation has, in recent years, released a range of grants that promote access to justice and clarification of land rights. These have typically been implemented by small, local, district- based NGOs, and little has been published of their successes and challenges. Transparency International Zambia has played a role in promoting improved land administration, including through the production of a guide on “Land Administration in Zambia: A guide to corruption free acquisition of land.”

The Zambia Land Alliance (ZLA) is a network of NGOs working for just and equitable land policies and laws that take into account the interests of the poor. The ZLA promotes secure access, ownership and control of land through lobbying and advocacy, research, and community participation (ZLA 2017). ZLA implements a number of advocacy, paralegal and systematic land documentation support programs across Zambia in part through its District Land Alliance Network.

Freshwater (Lakes, Rivers, Groundwater)

RESOURCE QUANTITY, QUALITY, USE AND DISTRIBUTION

Zambia lies within the Zambezi and Congo River Basins and has three main rivers, four large lakes, and roughly 1700 dams. Wetlands and dambos (shallow grassy wetlands in plateau areas) cover approximately 5 percent of Zambia’s total land area. The country is rich in water resources, such as the transboundary Zambezi and lakes Tanganyika, Mweru and Kariba, with 40 percent of the water in Central and Southern Africa passing through the country. The country has over 7580m3 per capita of annual internal renewable water resources. Agriculture accounts for 73 percent of water use; domestic use accounts for another 18 percent, and industry the final 8 percent. Annual freshwater withdrawals total 1.6 billion cubic meters. It is estimated that only 1.5 percent of the annual renewable water resources are being used at present. Water quantity and availability varies regionally, with some areas of the country like Western Province frequently experiencing severe drought. The annual rainfall averages between 1400 mm in the north and gradually declines to 700 mm in the south and groundwater availability is unevenly distributed (WHO/UNICEF 2015; W orld Bank 2014; F AO 2009).

Two million and seven hundred and fifty thousand hectares of land in Zambia are suitable for irrigation but only about 200 000 hectares are under active irrigation representing 7.3 percent of irrigable land utilization. Of this only 1500 hectares of land are irrigated within the lands over one million small-scale farmers, despite the presence of the Zambezi River. Emergent and large-scale farmers irrigate the remaining 198, 500 hectares. Most of the irrigated land lies along railway lines, above karstic areas for groundwater, adjacent to water bodies, and in dambos and wetlands (Hamukale 2015). The World Bank’s Irrigation Development Support Program has been piloting the provision of group titles to communities. This would allow them to gain access to large areas of land that can be irrigated and then sub-leased to agribusiness investors.

Fifty-one percent of rural Zambians have access to improved water sources, compared to 81 percent of the urban population. Water and sanitation are especially problematic in urban informal settlements. For example, the majority of informal settlements in Lusaka do not have sewers, and residents use alternatives such as pit latrines and septic tanks, which flows into groundwater, contaminating the environment and nearby water supplies. More than half of the people living in these settlements rely on boreholes for accessing water. Because the boreholes are often contaminated by raw sewage, disease is rife in these communities. In mining areas, the unrestricted discharge of effluents has polluted some local water resources. ( W orld Bank 2014; Y ubaNet 2008; Global W ater Partnership 2015).

Zambia has faced a number of challenges in managing their water resources, resulting in supply shortages, pollution, inadequate information for decision making, inefficient use, lack of financing and limited stakeholder awareness and participation (Global Water Partnership 2015). A particular concern over recent years has been the management of Kariba dam, which has not been able to meet annual electricity demand.

LEGAL FRAMEWORK

The 2011 Water Resources Management Act establishes the Water Resources Management Authority and defines its functions and powers. These include management, development, conservation, protection and preservation of Zambia’s water resources and its ecosystems for reasonable and sustainable utilization domestically and internationally as regards shared water resources specified in treaties. The Act provides for the right to draw or take water for domestic and noncommercial purposes, and that the poor and vulnerable members of the society have an adequate and sustainable source of water free from any charges. Provisions call for the creation of an enabling environment for improved adaptation to climate change and establish catchment councils, sub-catchment councils, and water users’ associations (GRZ 2011).

The 1997 Water Supply and Sanitation Act establishes the National Water Supply And Sanitation Council, with a mandate to provide for the establishment, by local authorities, of water supply and sanitation utilities and for the efficient and sustainable supply of water and sanitation services under the general regulation of the National Water Supply and Sanitation Council (GRZ 1997).

In 2013 Zambia co-sponsored General Assembly resolution 68/157, the first resolution where all UN Member States affirmed that the human right to safe drinking water and sanitation as legally binding in international law.

TENURE ISSUES