Overview

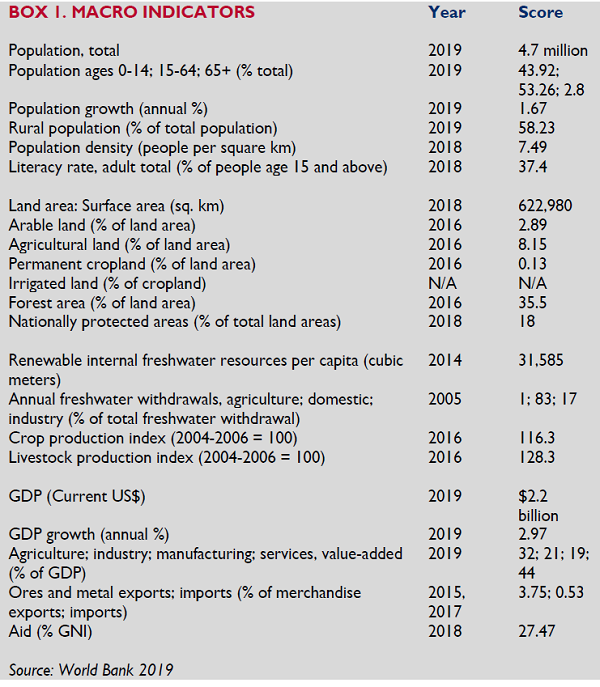

The Central African Republic (CAR) is a low-income, landlocked, resource-rich, and sparsely settled nation of 4.6 million people that occupies an area roughly the size of Texas. Constraints to realizing greater economic growth and human development are enormous: inadequate transport infrastructure; banking infrastructure incapable of supporting greater investments; low levels of technology; high levels of illiteracy; limited access to healthcare and education; and neighbors experiencing ongoing domestic and regional conflict (with frequent spillovers into the territory of the CAR). A major security crisis in 2013 resulted in the displacement of 25% of the population, and despite elections in 2016, the country faces enormous risks of instability and humanitarian crises moving forward. While USAID does not have a mission in Bangui, it is represented by one staff member. Insecurity has occasionally caused the US Embassy to close. The United States government (USG) provides development assistance largely through the USAID Mission of the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Governance of the mineral and timber resources of the country is of concern to the USG. The Congo Basin forest reserves are second only to those of the Amazon; many view the sustainable management of these reserves as a key to mitigation of climate change. While CAR does not possess the largest portion of the Basin forests, timber exports are an important source of export revenues, and the sector provides a substantial amount of employment. USAID’s Central Africa Regional Program for the Environment (CARPE) includes assistance to CAR thanks in part to the Sangha Tri-National park – one of CARPE’s 12 priority landscapes. With a mandate from the US Clean Diamond Trade Act, the USG is committed to ensuring that the CAR’s diamond reserves are managed under the Kimberley Process Certification Scheme (KPCS), which tracks the source of diamonds with the intent to halt the trade in “conflict” diamonds, and appropriately recognizes the role property rights held by small-scale artisanal diamond miners plays in strengthening community monitoring of illicit trade. The phases of the Property Rights and Artisanal Diamond Development (PRADD) projects, which ran from 2007 to 2013, demonstrated practical ways to achieve these goals. Following the 2013 crisis, CAR was suspended from the KPCS and the follow-on PRADD II project (2016-2018) assisted the government to comply with a new Operational Framework that allowed partial resumption of trade. The Artisanal Mining and Property Rights Project (AMPR) began in 2018 and is continuing these efforts while also paying attention to the country’s burgeoning gold sector.

The majority of CAR’s population is rural, dependent largely on farming or livestock production (primarily transhumance pastoralism centered migration of cattle for pastures and water). Conflict and violence have periodically displaced people from their homes, increasing the threat of hunger and food insecurity. As of mid-2020, an estimated 2.6 million people required humanitarian assistance in CAR, including 2.4 million people facing food insecurity (USAID 2020). The COVID-19 global pandemic has exacerbated risks due to supply chain disruptions, lockdown measures, and the direct effects of disease. Because poor transport and market infrastructure have limited the potential for commercial production and possible export to neighboring countries or world markets, much of the production is destined only for family consumption or local-market sale. Two-thirds of the population is estimated to live below the poverty line. The United Nation’s Human Development Index has placed CAR at or near the bottom of the rankings for many years. Greater security of land tenure rights could help to increase investments for productivity, especially in small irrigation facilities and for women farmers, but an array of other interventions will also be needed to improve the productivity and performance of the agricultural and livestock sector overall. Managing conflict between transhumant pastoralists and other livelihood groups is an emerging priority.

Key Issues and Intervention Constraints

CAR’s legal framework for surface and sub-surface land rights is dated, and the administrative structures established to govern them have limited reach. While more work has recently been done to establish a Forest Code that recognizes different users of forest products and services, growing markets for tropical woods and the possibility of greater exports through the Democratic Republic of the Congo may challenge the government in its implementation of the 2008 Code. Donors have several opportunities to collaborate and with the government to develop a relevant legal framework (and implementing institutions) for land and forest rights. USAID has already made some contributions through its CARPE support, for example, but it could also draw on significant experience with legal frameworks and comparative knowledge of those in comparable countries to design and draft a comprehensive framework that: (1) capitalizes on the strengths of the country’s customary laws and traditional institutions; (2) provides the architecture for adoption of the rule of law and realization of the principles of equity and justice set forth in the country’s Constitution; (3) integrates principles of decentralization of governance; and (4) provides for the protection and improvement of the rights of women and marginalized populations such as forest dwellers, pastoralists, and nomadic herders.

Urbanization accelerated during the years of civil conflict and violence, and an estimated 40% of the CAR’s population resides in urban areas. Little is reported about the numbers of people living in informal settlements in peri-urban and urban areas or their settlement conditions. A focused assessment of urban land tenure conditions could enable donors – and the government – to ensure that an appropriate legal framework for formalizing the rights of squatters, displaced persons, and others are put in place.

The PRADD projects were useful mechanisms for the United States to engage with the CAR on critical issues of resource governance even without a fulltime USAID presence in-country. In late 2012, multiple donors (GIZ, FAO and USAID) collaborated on a policy dialogue on rural land tenure, but progress was cut short by the 2013 coup d’état. The USAID AMPR project has taken stock of lessons learned from PRADD and is revitalizing property rights clarification and natural resource management through pilot artisanal mining zones (zones d’exploitation artisanale). Donors could consider further activities aimed at decentralizing control over natural resources and developing community-based natural resource management models.

Summary

The Central African Republic (République Centrafricaine, CAR) is a landlocked, sparsely populated country that is well-endowed with natural resources. CAR has abundant land, adequate soil, dense tropical forests, and a wealth of unexploited minerals. However, the country has a history of political instability and authoritarian regimes and military dictatorships alternating with one-party rule. The 2013 coup d’état by the Seleka rebel coalition led to new instability and inter-community violence that displaced 25% of the country’s population. The UN established the MINUSCA peacekeeping mission in 2014, elections were organized in 2016, and the government and rebel groups signed the Khartoum agreement in 2019. However, opposition parties and non-state armed groups continue to vie for political power, and instability remains a threat.

The history of political unrest and violence has paralyzed the country’s development. CAR has only 650 kilometers of paved road, no railroad, and limited air transportation. The country lacks basic services, hospitals, and schools. The country was ranked 188 out of 189 countries in the 2018 Human Development Index and has been at or near the bottom for decades. Seventy-one percent of the population lives below the international poverty line. Forty percent of the population suffers from chronic malnutrition. Sixty-three percent of men and women are illiterate. Life expectancy in CAR in 2018 was 52 years.

The history of political unrest and violence has paralyzed the country’s development. CAR has only 650 kilometers of paved road, no railroad, and limited air transportation. The country lacks basic services, hospitals, and schools. The country was ranked 188 out of 189 countries in the 2018 Human Development Index and has been at or near the bottom for decades. Seventy-one percent of the population lives below the international poverty line. Forty percent of the population suffers from chronic malnutrition. Sixty-three percent of men and women are illiterate. Life expectancy in CAR in 2018 was 52 years.

Large swathes of the country remain under de facto control of various armed groups. Despite signing an agreement with 14 of them in 2019 under the Khartoum Agreement, insecurity remains a problem, with many armed groups earning illicit revenue through roadblocks, protection rackets for transhumant pastoralists, and illegal gold and diamond mining and trade. In the first half of 2020, 230 security incidents were recorded (USAID 2020) including 2 deaths, making CAR among the riskiest places in the world for humanitarian workers. Despite improvements from the peak of the crisis in 2013-2015, around a quarter of CAR’s population remains displaced due to violence.

Eighty percent of the population relies on subsistence agriculture and livestock for their livelihoods. Lack of infrastructure, weak purchasing power, and violence have constrained the development of markets. Land rights throughout much of CAR are considered insecure as a result of political instability, lack of confidence in the government, weaknesses in government institutions, and widespread social unrest.

The potential in CAR’s land and other natural resources has yet to be realized: roughly a third of the country is considered suitable for farming, yet only about 3% is under cultivation. Close to half of CAR’s land is suitable for livestock grazing yet less than 15% is used. Transhumant pastoralists from neighboring countries migrate seasonally to the country in search of pastures and water and this is a source of conflict and violence from increasingly well-armed herders. Conflicts are especially complex, mainly because pastorals herd their livestock beyond national borders and transhumance migration creates new settlement fronts. CAR is rich in forest resources, providing the population with fuel, food, shelter, medicinal plants, grazing land, and building materials. The timber industry serves as CAR’s main source of export earnings. This growth will have to be managed well to guard against the overexploitation of CAR’s share of the Congo Basin forest and biodiversity resources. CAR also possesses considerable mineral and petroleum wealth, most of it unexplored and unexploited, in part because political instability and conflict have provided few incentives to larger foreign investors and buyers. Despite these challenges, rough diamonds and gold mined largely by extremely poor miners with limited mechanization are key mineral exports and the second most important source of export earnings.

Background

LAND USE

The Central African Republic has a total land area of 623,000 square kilometers. The 2018 population was 4.9 million, with 61% rural and 39% urban. The country’s GDP in 2018 was US $2.2 billion. Thirty-one percent of GDP was attributed to agriculture, 42% to services, and 20% to industry. The main export crop is cotton (World Bank 20018).

Roughly one-third of CAR’s total land is considered suitable for farming. Approximately 8% of the land is under cultivation (FAO 2016), 0.1% of cropped land is irrigated, and 5% is pastureland. The potential in the land has yet to be realized: roughly a third of the country is considered suitable for farming, yet only about 3% is under cultivation. Close to half of CAR’s land is suitable for grazing yet less than 15% is used (GOCAR 2007, World Bank 1998, Furth 1998, UNSC 2006).

Eighty percent of the population relies on subsistence agriculture and livestock for their livelihoods. Despite this, inter-ethnic and religious conflict and violence have taken a toll. In the north, west, and east of the country, bandits and rebels have burned villages, pastureland, and cropland. Seed stocks have been lost, irrigation infrastructure destroyed, and the population chased from homes, leading to declining land-use and productivity. During the years of conflict, an estimated 60% of livestock owners fled to neighboring countries to preserve their stock, and thousands of farmers abandoned their farms. As of September 2020, there are 659,000 internally displaced persons and 624,000 Central African refugees in neighboring countries (OCHA 2020).

Forests cover 35% of the country, and 15% of the total land is classified as nationally protected areas. Deforestation is occurring at a rate of 1.8% annually (UNDP 2018).

LAND DISTRIBUTION

CAR is home to more than 80 ethnic groups, the largest of which are the Baya (33%), Banda (27%), and Mandjia (13%). Some groups, such as the 20,000 Baka pygmies who live in the country’s dense forests, are quite isolated, almost entirely dependent on natural resources for their livelihoods, and vulnerable to exploitation from outside interests. Nearly three-quarters of the population of CAR is below the international poverty line, 40% suffers from chronic malnutrition, and the country has ranked near the bottom of the Human Development Index in recent years (WFP 2009, UNHCR 2010, UNDP 2018, Foreign Policy 2009, AfDB 2009a).

Most cultivated land in CAR is used for subsistence farming; farm sizes average between 1.5 and 2 hectares – the amount an average family can cultivate and protect. Most farmers use traditional cultivation methods, and productivity is low. In the past, transhumant livestock herders obtained relatively high returns from migrating seasonally from the northern drylands to the more humid south. Livestock production is threatened because herds have been decimated by bandits and rebel forces. Persistent insecurity in the north has hindered the resumption of farming and livestock activities (HDPT 2008, IPIS 2018, UNDP 2006, FAO 2005).

Most cultivated land in CAR is used for subsistence farming; farm sizes average between 1.5 and 2 hectares – the amount an average family can cultivate and protect. Most farmers use traditional cultivation methods, and productivity is low. In the past, transhumant livestock herders obtained relatively high returns from migrating seasonally from the northern drylands to the more humid south. Livestock production is threatened because herds have been decimated by bandits and rebel forces. Persistent insecurity in the north has hindered the resumption of farming and livestock activities (HDPT 2008, IPIS 2018, UNDP 2006, FAO 2005).

About 41% of CAR’s population lives in urban areas, mostly in the capital city, Bangui. Most of the recent migrants to the city fled violence in rural areas, and they are among the country’s poorest people. With no means to afford housing in planned, serviced areas, they crowd into the informal settlements where they live in substandard, unsafe housing, often without basic services such as water and sanitary services (Tayoh 2009, GOCAR 2007, UN Data 2010).

The northern, western, and eastern regions harbor rebel fighters and bandits who seize entire villages, steal livestock and equipment, exploit minerals illegally and burn agricultural fields and food storehouses. As of September 2020, in addition to the 624,000 citizens of the CAR living as refugees in neighboring countries, the CAR had about 659,000 internally displaced persons (IDPs) (OCHA 2020).

LEGAL FRAMEWORK

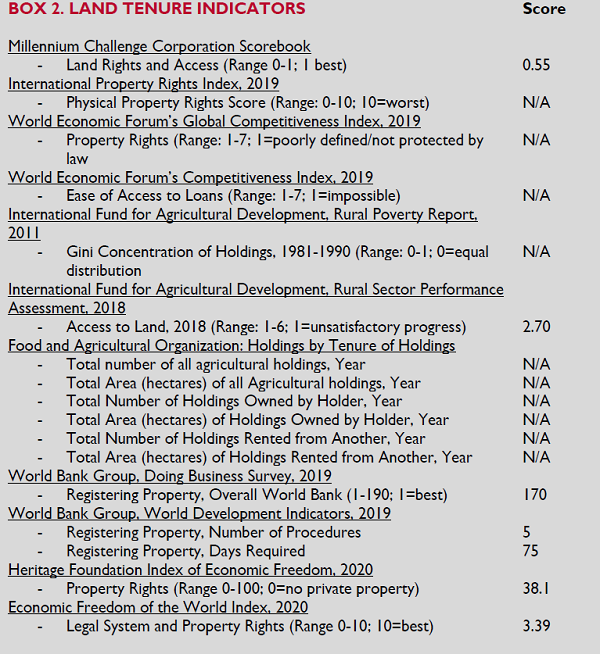

The 2016 Constitution of the Central African Republic provides that all persons have a right to property, and the state and citizens must protect those rights. CAR’s Law No. 63 of 1964 (Loi No. 63.441 du 09 janvier 1964 relative au domaine national) abrogated the prior (and more comprehensive) Law No. 139 of 27 May 1960, which governed land tenure, and Law No. 60/76, which allowed individuals to obtain occupancy rights to land identified by the state for habitation. Law No. 63 of 1964 defines the national domain and anticipates additional laws to address land tenure and private property. To date, no additional laws have been enacted; Law No. 63 of 1964 remains the primary formal law governing land rights in CAR. Law No. 63 recognizes customary law but limits customary land tenure to use-rights. The law provides for the privatization of state land through land registration (GOCAR Constitution 2004; Tetra Tech 2007a; GOCAR 2006).

TENURE TYPES

Under Law No. 63 of 1964, state land is classified as either within the public domain of the state or the private domain of the state. The public domain of the state includes natural property (such as rivers) and artificial property (such as roads). The private domain of the state includes all unregistered land as well as landholdings that the state acquires through transactions and the exercise of eminent domain. Private parties can obtain private property rights to land in the state’s private domain (Tetra Tech 2007a).

The following tenure types exist in CAR:

Private ownership. Under CAR’s formal law, an individual or entity can obtain ownership rights to land through registration of their interest as private property. Occupants of land can apply for ownership rights under the principle of mise en valeur, which awards ownership rights to those who develop their land intensively (e.g., employing intensive or permanent agriculture) over a prescribed long period. Ownership rights may be transferred by purchase, inheritance and lease. Less than 0.1% of land in CAR is registered (Tetra Tech 2007a, Furth 1998, World Bank 2008, World Bank 1998).

Leaseholds (private and state land). Individuals, groups, and entities can lease land from the state or private parties under formal law and customary law. Leases of land within the state’s public domain are granted for definite periods, generally not exceeding 20 years; no lease can extend beyond 50 years (Tetra Tech 2007a, Furth 1998).

Concessions/private ownership option. The state can grant concessions of land in its private domain to individuals and entities as concessions. The concessionaire must develop the land or extract mineral resources per the terms of the concession within two years for urban land, and within five years for rural land. Concessionaires who have developed the land per the agreement and obtained the approval of the local government may apply for private ownership rights to the land (Tetra Tech 2007a).

Right of habitation (state land). The state’s recognition of occupancy rights to certain land has continued despite the absence of formal law providing for rights of habitation. Upon application, the state issues a habitation permit that allows the applicant to occupy the land and erect any nonpermanent structure, including huts of organic materials. In some areas, the permits are free and easily obtained. In peri-urban areas, permits are difficult to obtain and often require large payments and the permission of multiple officials. The length of time for which habitation permits are granted is unknown (Furth 1998, Tetra Tech 2007a). Transhumant pastoralists are accorded rights to graze on state and private lands with livestock migration routes a central feature of the Pastoralist Code, but these provisions are now outdated and very much in need of substantial revision (International Crisis Group 2014). While conflict between pastoralists, sedentary agricultural peoples, and artisanal gold and diamond miners is pronounced in the southwest, policy initiatives to address complex resource access are not yet in place and, for this reason, local peace and reconciliation committees address as best they can the symptoms of the problems.

Customary tenure. Law No. 63 of 1964 recognizes use-rights to land-based on principles of customary law. Customary law is a localized and evolving system deeply influenced by the decades of conflict and violence. Some general principles of customary law that are common to the central African region apply in the CAR, such as land being held collectively by the lineage or clan and the right of the first clearer of land to use the land. As the commercial value of land has increased, customary landholdings have become increasingly individualized and passed by inheritance within families (Tetra Tech 2007a, Furth 1998, FAO n.d.). As in many parts of Africa, rural populations believe that they have rights to sub-surface resources, and complex benefit sharing and taxation arrangements from mining are widespread. However, the state claims all rights to sub-surface resources. The AMPR project is piloting the creation of Zones d’Exploitation Minier (ZEA) zones which would recognize in effect customary rights to artisanal alluvial mining areas.

SECURING LAND RIGHTS

Under formal law, individuals, entities, and groups can acquire land rights through purchase, concession, and land development (application of the principle of mise en valeur) and rental. Individuals, entities, and groups desiring ownership rights to land under formal law must apply for legal title and register the land. According to the World Bank’s Doing Business survey, registering property in CAR requires five procedures, averages 75 days, and costs 18.5% of the property value. Ownership rights must be secured through registration of the titles in the official land register. Only an estimated 0.1% of land in CAR is titled and registered. Registered land includes urban land in serviced areas and some commercial plantations. In peri-urban and urban areas, people can apply to the government for habitation permits, but they are often difficult and expensive to obtain (World Bank 2008, World Bank 1998, Furth 1998).

Most people typically obtain access to rural land through inheritance and allocations from the lineage heads, who control land distribution and allocation under customary law. Most urban and peri-urban residents live in informal settlements either as squatters or with occupancy rights purchased on the informal market and recognized under customary law. CAR does not have legislation providing for the formalization of informal settlements (World Bank 2008, World Bank 1998, Furth 1998).

Land rights throughout much of CAR are considered insecure as a result of political instability, lack of confidence in the government, weaknesses in government institutions, and widespread social unrest. Violence has displaced communities and destroyed villages and agricultural land, and some people who fled from their land have been permanently resettled elsewhere (Furth 1998, UNHCR 2010, UNSC 2006).

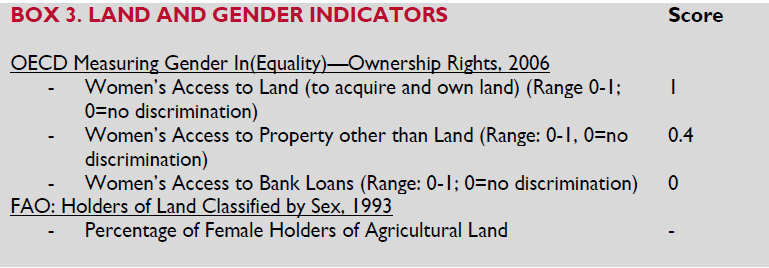

INTRA-HOUSEHOLD RIGHTS TO LAND AND GENDER DIFFERENCES

The CAR Constitution guarantees equal rights to women and men and the right of all people to hold property. Whether the formal law permits joint titling of property is unknown, as is the incidence of joint titling. The 1998 Family Code provides for equal rights of women in marriage and divorce, and under formal law daughters and sons have equal rights to inherit property. However, the customary law and traditional practices that continue to govern the rights and obligations of people in CAR—despite the enactment of formal laws—do not grant women equal status. Under customary law, men own marital property, and land rights transfer from the eldest male in the lineage to the next eldest male. As customary land tenure has become more individualized, families claim rights to transfer land within their families, and land passes from the father to son (GOCAR Constitution 2004, GOCAR 2000, USDOS 2001).

Eighty-six percent of the female labor force was reportedly engaged in agricultural activities (compared to 64% of the male workforce) in the 1990s, yet almost none have rights to the land they farm. Women who are single, divorced, or widowed are not considered heads of households and are not considered to be landholders, only land users. Widows, and sometimes their children, are often evicted from their property by the deceased husband’s family. In households without an adult male family member, land rights will often

Eighty-six percent of the female labor force was reportedly engaged in agricultural activities (compared to 64% of the male workforce) in the 1990s, yet almost none have rights to the land they farm. Women who are single, divorced, or widowed are not considered heads of households and are not considered to be landholders, only land users. Widows, and sometimes their children, are often evicted from their property by the deceased husband’s family. In households without an adult male family member, land rights will often

be held by another male relative such as an uncle or cousin instead of a woman. Polygamy is legal in CAR, and men can take up to four wives. The 28% of women who are in polygamous relationships, including 21% of girls aged 15–19, have no rights to property (OECD 2008, World Bank 1998, GOCAR 2000).

Women in CAR often lack the education and social status to assert their legal rights. Sixty-eight percent of women in CAR (compared to 46% of men) are illiterate. Women are poorly represented in the country’s political and administrative bodies (under 5%). Fewer than 3% of judges and lawyers in the country are female, and legal-aid services in the country are limited (UNDP 2008, GOCAR 2000).

LAND ADMINISTRATION AND INSTITUTIONS

The CAR’s Land Registry (Conservation Foncière) is responsible for maintaining the cadaster and recording land transactions. Very little land (an estimated 0.1%) is registered in CAR (IMF 2009a, World Bank 2008).

The Ministry of Agriculture is responsible for planning, supervising, and coordinating the country’s agricultural policy and programs. Two governmental bodies, the Central Agency for Agricultural Development and the Central Institute of Agricultural Research, are responsible for the coordination and execution of training and research, respectively.

Under customary law, which dominates land access and tenure for most of the population of CAR, lineage heads and chiefs have traditionally controlled land distribution and allocation. In recent years, the chiefs, who are often government employees, have begun to serve as intermediaries between people seeking land in certain areas and the relevant lineage heads (Furth 1998).

LAND MARKETS AND INVESTMENTS

There is no formal land market in CAR, although there is evidence of the increasingly commercial value of land, especially in areas with significant natural resources (such as minerals) and serviced plots in urban areas. Individuals and entities seeking private ownership of land can obtain a concession for state land, which with local government approval can be transferred into an ownership interest. The government uses rental values to determine a tax base in urban areas but has difficulty collecting taxes. The extent to which an informal land market operates in CAR is unclear (Tayoh 2009, Tetra Tech 2007a) but transactions have been observed in the diamond sector (USAID 2012).

COMPULSORY ACQUISITION OF PRIVATE PROPERTY RIGHTS BY GOVERNMENT

Article 14 of the 2016 CAR Constitution provides that no one can be deprived of property except upon a legally sound showing of public purposes and on payment of compensation before the taking. The state can also repossess any land that it deems has not been put to proper use, a concept that is broadly defined. Law No. 63 of 1964 includes the principle of eminent domain as an extension of the state’s public domain. The state has the authority to acquire land for purposes of urban planning, public security, aesthetics, and development of rights of way, and services such as communications and sewer systems. The extent to which the government has exercised its right of eminent domain and the circumstances of governmental land takings is unknown (GOCAR Constitution 2016, Tetra Tech 2007a, Furth 1998).

LAND DISPUTES AND CONFLICTS

CAR’s formal judiciary is weak and lacks independence from the executive branch. Court decisions often lack objectivity, are politically and tribally motivated, and are contrary to existing law. Court procedures are lengthy and costly, and the right to a fair trial is not guaranteed. The court system suffers at all levels from a shortage of trained personnel, a lack of essential materials and resources, and corruption plagues the lower courts. The extent to which traditional systems of dispute resolution and customary forums are in use in CAR is unknown (ICJ 2005, FP 2009). However, in the diamond sector, local chiefs and associations of miners play a role in resolving disputes regarding mining claims (USAID 2019b). In addition, the Certificates of Customary Land Tenure issued under the USAID PRADD project were used in case of disputes and reduced the amount of conflicts (USAID 2012, 2019b).

Traditionally, women in CAR were engaged in dispute prevention and resolution. Women are considered the family and community members who represent principles of peace and harmony, and chiefs and councils of elders sought out the judgment of women in resolving community disputes and facilitating conflict resolution. The extent to which traditional dispute resolution forums currently include women is unknown, but NGOs in CAR are working to revive the tradition as a means of reducing social unrest and stabilizing the country (Mathey et al. 2001). Over the past years, international humanitarian organizations have worked closely with the government to set up popularly elected Peace and Reconciliation Committees. These new structures bring together well-respected community peace-makers to resolve local disputes and who, as in the case of committees supported by the AMPR project, establish Local Pacts or community-supported conventions to formalize arrangements among contesting parties (USAID 2019b).

KEY LAND ISSUES AND GOVERNMENT INTERVENTIONS

CAR has a history of authoritarian regimes and coups, most recently in 2013. However, CAR’s new government in 2016 began efforts toward strengthening its core state institutions and bodies. The government continues to be challenged by rebels and has been unable to exert much control over a majority of its remote provinces (World Bank 2018, Foreign Policy 2009, UNESCO 2006, FP 2009).

The government began the process of creating a new land tenure policy in 1986 to update colonial-era land policy and land legislation from the early 1960s. The government was unable to reach sufficient agreement and garner enough political support for the new policy’s adoption. In 2012 donors assisted the government to begin a policy-making dialogue on land tenure including a high-profile workshop with the Prime Minister, but this effort ended with the 2013 fall of the government to the Seleka rebellion. No new efforts to adopt a policy or draft a land law are reported. The government has identified agriculture as an area for growth and development. The government plans to boost existing initiatives by providing funding for agricultural equipment, inputs, and marketing; relaunching production chains; promoting agricultural product processing; and providing marketing support (GOCAR 2007, World Bank 1998, Furth 1998). However, most donor resources since the 2013 crisis have focused on humanitarian emergencies and security (OCHA 2020).

DONOR INTERVENTIONS

Most of the work of donors in CAR is directed toward humanitarian aid, security, and restoration of systems that have been destroyed by political upheaval and violence. USAID does not have a mission in CAR, but it does have a local representative. Most USAID programming is run through the DRC Mission. USG humanitarian assistance in the fiscal year 2019 was more than $144 million (USAID/DCHA 2020). The Artisanal Mining and Property Rights (USAID AMPR) project set to run from 2018 to 2023 is the only initiative in CAR to look at land tenure issues with a focus on its linkages to diamond sector good governance.

The FAO has been engaged in restoring agricultural production systems and assisting the agricultural sector to cope with the loss of equipment and seed stocks due to violence and social insecurity. The FAO has 4 main priorities: support an improved production environment; rural development and improved food and nutrition security; prevention and management of food crises, natural disasters and humanitarian emergencies, including early warning, human disease control and disaster risk reduction; development of regional and subregional cooperation to ensure continual agricultural recovery. The World Food Programme (WFP) is operating a food-for-agricultural-work program, and Mercy Corps is engaged in agricultural development initiatives, including seed-distribution programs. None of the programs appear to have components addressing issues of land access and tenure security (FAO 2006, WFP 2009, Mercy Corps 2009).

Since the 2013 crisis, humanitarian organizations have worked on community-level peace and reconciliation, asset restitution of returning refugees, mainly, Muslims. The assets have included land, houses and other property. The Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC), for example, has facilitated dialogue around asset restitution for 52,000 returnees since January 2019 (NRC 2020). However, no donor or organization is currently looking explicitly at land tenure and property rights policy as a whole though before the coup d’état, FAO collaborated closely with the Ministère de l’Urbanisme on land policy reform.

Freshwater (Lakes, Rivers, Groundwater)

RESOURCE QUANTITY, QUALITY, USE AND DISTRIBUTION

The Chad Basin in the north and the Congo Basin in the south are the foundation of CAR’s water resources. The rivers flowing from the two basins and their tributaries travel in opposite directions and provide surface water for the entire country. The Ubangui River, one of the tributaries of the Congo River, forms part of the southern border between CAR and the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). The country’s southern tropical zone receives between 1500 and 1800 millimeters of rainfall per year. The Sudano-Guinean zone in the center of the country has a tropical moist climate, receiving about 1100–1500 millimeters of rainfall annually. The northern Sudano-Sahelian band receives between 800 and 1000 millimeters per year, and the dry Sahelian zone further north has erratic rainfall and frequent droughts.

CAR’s internal renewable water resources amount to 141 cubic kilometers per year. Eighty percent of CAR’s water is used for agriculture, 16% for domestic use, and 4% for industry (World Bank 2009a, GOCAR 2006, FAO 2005, Tetra Tech 2007a).

The country’s water levels are declining, and surface water quality is rapidly deteriorating, suffering from pollution from human waste and serving as a vehicle for disease. Only about 32% of the rural population has access to safe drinking water, and about 10% of the population has access to sanitation facilities. Urban centers were better served until the most recent years of political upheaval (1996–2003), during which much of the water supply system and infrastructure for water delivery and sanitation were destroyed or collapsed. By 2008, roughly 30% of the urban population had access to safe drinking water (UNESCO 2006, FAO 2005, AfDB 2009b).

LEGAL FRAMEWORK

CAR’s 2006 Water Code (Loi No. 06.001 de 12 avril 2006 Portant Code de L’eau de la République Centrafricaine) provides that all of the country’s surface and subterranean water is in the public domain. No one can prevent the free movement of the country’s surface and groundwater, and any use of the water must be authorized by the government. The Water Code does not expressly recognize customary water rights (Tetra Tech 2007a).

The 2006 National Water Supply and Sanitation Policy (Décret No. 06.170 de mai 2006 Portant Adoption de Document de Politique et Strategies Nationals en Matière d’Eau et d’Assainissement en République Centrafricaine) embraces an integrated water resources management approach; the policy does not reach issues of the water rights of individuals or communities but anticipates future revisions to the Water Code and recognition of customary water rights. The Water Code recognizes the existence of “sacred waters” and provides for their protection by community leaders (Tetra Tech 2007a, GWP 2006, FAO 2009, WHO 2000).

TENURE ISSUES

The Water Code provides that the country’s surface and subterranean water is the patrimony of the state. Authorization is required for water use and diversions. The Water Code grants an exception for water collected from rainwater or through private construction efforts, such as an artificial basin. Such water is considered the private property of those who made the effort to collect it (Tetra Tech 2007a).

The Water Code provides for the imposition of water user fees. Water users are also responsible for paying for any pollution of water resources or damage to water quality. The extent to which the government can collect fees or enforce anti-pollution measures is unknown (Tetra Tech 2007a).

While little is reported regarding customary water rights in CAR, customary water law in the region includes the following general principles: (1) water resources are owned by the clan or community and should be managed in a manner that allows all members to have access to water; (2) water rights attach to land rights, and landholders generally have free and unlimited access and use-rights to water on their land; (3) rights to control water sources are often earned with the amount of labor and resources expended to develop the water source; (4) landholders may not divert or block watercourses that traverse their land, and (5) pastoralists and other migrant populations should have rights to use community water but should obtain the permission of the community or clan leader and abide by any restrictions imposed (Orindi and Huggins 2005).

GOVERNMENT ADMINISTRATION AND INSTITUTIONS

The Ministry of Water, Forestry, Hunting and Fisheries has authority over the country’s water resources. The Ministry of Agriculture and Livestock has authority over irrigation water and systems, and the Ministry of Public Works is responsible for urban water supplies and systems (GWP 2006, FAO 2005).

GOVERNMENT REFORMS, INTERVENTIONS AND INVESTMENTS

The government of CAR is a member of the Global Water Partnership, which is committed to the Integrated Water Resources Management Approach (IWRA) to water management. The IWRA is based on the recognition that water has ecological, social and economic uses, and that water management has to recognize the various uses and integrate separate systems to the extent possible. CAR’s National Water Supply and Sanitation Policy and the Water Code were significant steps toward the adoption of a regulatory framework that embraces the philosophy of equitable and sustainable management of water resources and support for providing access to safe drinking water and sanitation facilities nationwide. The government has also targeted the development of irrigated agriculture and has set the following goals: the development of a master plan for irrigation, the promotion of vegetable cultivation in peri-urban areas, and development of irrigation systems for 3000 hectares of lowland and 1000 hectares of land used by small market gardeners by 2010 (GWP 2006, FAO 2005, AfDB 2009b).

DONOR INTERVENTIONS AND INVESTMENTS

Most donor interventions and investments focus on humanitarian emergency response rather than overall water policy or infrastructure investments. For example, the CAR Humanitarian Fund coordinated by OCHA and administered by over 40 organizations includes more than 289,000 people targeted for WASH support (OCHA 2020).

Trees and Forests

RESOURCE QUANTITY, QUALITY, USE AND DISTRIBUTION

CAR has about 23 million hectares of forestland, an estimated 1800–3000 hectares of plantation timber, and a 1000- hectare rubber plantation. CAR’s forestland is highly diverse, including the Sudano-Sahelian steppes in the northeast of the country, dry and wooded savanna, woodlands, and dense equatorial forests in the southern region. The semideciduous rainforests in the southwest corner of the country and south-central area along the border with the DRC are some of the densest in Africa. The majority of the country’s extensive protected areas (15% of total land) are in the northeastern section of the country; in 2005, only 300,000 hectares of closed forest was protected (ITTO 2005, APFT n.d., IRIN 2007, Ngatoua n.d., Usongo and Nagahuedi 2008).

Forestland provides CAR’s population with sources of fuel, food, shelter, medicinal plants, grazing land, and building materials. The forest is home to 20,000 pygmies, most of whom rely entirely on forest products for their livelihoods. CAR’s forests include about 200 species of mammals (including gorillas, bongos, and forest elephants), 670 bird species, and 3600 species of plants. Nine of the mammal species are endangered or threatened (ITTO 2005, IRIN 2007, Mathamale et al. 2009).

Environmental degradation is less severe in CAR than in other parts of central Africa. The violence and social instability have caused people to migrate from rural areas to urban centers, which has taken some of the pressure off the forests to provide for livelihoods. Nonetheless, deforestation is occurring at about 1.8% per year, mostly attributed to farmers clearing forests for agriculture, logging, and bushfires. The timber industry has extensive operations in CAR’s forests and has historically provided roughly half of CAR’s export earnings (World Bank 2018). In 2018, 11 timber companies were operating in 14 licenses with management plans representing 3.625 million hectares in the southwestern forests. As the industry expands into increasingly larger areas of CAR’s forestland and cuts logging roads that increase access to the forest, deforestation, and overexploitation of non-timber forest products increases (AfDB 2009a, Usongo and Nagahuedi 2008, IRIN 2007, ITTO 2005, World Bank 2009a).

LEGAL FRAMEWORK

The current CAR Forest Code (Code Forestier de la République Centrafricaine) was adopted in October 2008. The Forest Code provides for state ownership of the country’s forests and divides the forests into the permanent forest domain and non-permanent forest domain. The country’s permanent forests are located in Bangassou in the eastern part of the country and the southwest forest system. Non-permanent forests are those created by local governments, individuals, and groups through arboriculture and forest restoration activities (Tetra Tech 2007a).

The Forest Code recognizes customary rights to forest resources, granting local communities use-rights to forest land and forest products. All use-rights recognized by the formal law are subject to state definition and control (Tetra Tech 2007a). The code also creates a framework for providing a percentage of tax revenues to local communities and decentralized entities for local investments (World Bank 2018).

The Yaoundé Declaration of 1999, which was signed by CAR, Cameroon, Chad, Democratic Republic of Congo, Republic of Congo, Equatorial Guinea, and Gabon, established an international framework for collaboration on cross-border forest issues, the creation of protected areas, and the development and implementation of coordinated sustainable forest management. The declaration also created a governance structure, the Central African Forests Commission (COMIFAC), which has the authority to direct, coordinate, harmonize, and monitor forest and environmental policies in the region (Usongo and Nagahuedi 2008).

CAR is also a member of the Voluntary Partnership Agreement (VPA) with the European Union within the framework of the Forest Law Enforcement Governance and Trade (FLEGT) process. This has improved standards of production concerning sustainable forestry management.

TENURE TYPES ISSUES

Under the Forest Code, the permanent forest domain includes state forest domain and public forest domain and encompasses all economically exploitable forest resources. The majority of the country’s forestland is state forest domain, including production forests, forest reserves, game parks, and forests that are subject to industrial and artisanal exploitation permits. The state has the authority to grant forest exploitation and development permits for an unlimited time. The Forest Code assigns local villages and/or indigenous communities a decision-making role in the granting of exploitation permits and requires the entities receiving exploitation and development permits to contribute to the social well-being of the local communities. The state must also consult with the local population, including indigenous communities, before granting a concession for industrial exploitation of the forest. Artisanal permits are available for small-scale and non-mechanized exploitation of forest resources (Tetra Tech 2007a, Mathamale et al. 2009). Local decentralized entities also have the right to a percentage of forestry tax revenues through accessing these funds requires submitting a project proposal to the central government.

Individuals and entities developing non-permanent forests can obtain rights to forest resources, consistent with government regulations (Tetra Tech 2007a).

GOVERNMENT ADMINISTRATION AND INSTITUTIONS

The Ministry of Water, Forests, Hunting and Fisheries (MEFCP) is responsible for the management of the country’s forests. The country is in the process of developing the capacity to manage natural resources, including capacity within the MEFCP, which has suffered from the lack of a legal framework and governance structure, lack of human and financial resources, inability to manage areas affected by conflict, and corruption. CAR’s first Poverty Reduction Strategy Paper (PRSP) (2008–2010) included support for MEFCP.

In May 2000, the CAR, Cameroon, Chad, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Equatorial Guinea, and Gabon (signatories of the Yaoundé Declaration) established COMIFAC as the governance body for the Congo Basin forests. A treaty in 2005, in which these countries were joined by Angola, Burundi, Rwanda, São Tomé and Príncipe, made COMIFAC into a legal entity with the responsibility to coordinate all conservation measures in the region. The regional umbrella structure, the Congo Basin Partnership, brings together all stakeholders (governments, NGOs, indigenous forest peoples’ groups, researchers, donors, the private sector, and civil society) to implement Congo Basin initiatives (Usongo and Nagahuedi 2008, CBFP 2010).

CAR is also a member of the Congo Basin Forest Partnership (CBFP), which was launched at the 2002 World Summit on Sustainable Development in Johannesburg as a voluntary multi-stakeholder initiative contributing to the implementation of the Yaoundé Declaration. All COMIFAC countries are members of the CBFP, along with other member governments (Canada, France, Germany, Spain, Japan, South Africa, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, Norway, United States, and the European Commission), donor agencies, international organizations, NGOs, scientific institutions, and representatives from the private sector. CBFP works in close relationship with COMIFAC and serves as a conduit for communication between donors and implementing agencies and provides a forum for dialogue and cooperation among partners (CBFP 2010).

GOVERNMENT REFORMS, INTERVENTIONS AND INVESTMENTS

In 1990, CAR established 120,000-hectare Dzanga-Sangha Special Dense Forest Reserve. The Sangha Tri-National Area, which includes the reserve, is identified as one of 12 priority areas for the Central African Regional Program for the Environment (CARPE). The government has adopted a partnership approach to managing the reserve that includes engaging the local communities. A local nongovernmental organization, the Committee for Development of Bayanga (CDB), was created to facilitate the participation of local communities in decision-making relating to the reserve. International conservation NGO WWF has been the main partner of the park and its neighboring communities.

The government’s Poverty Reduction Strategy Paper for 2008–2010 identified the need for good governance in the management of the country’s forest resources to increase the sector’s value. In addition, the government’s Strategy for Recovery and Peacebuilding (RCPCA) adopted in 2016 also calls for support to poverty reduction and economic development. In order to join the EU-FLEGT initiative, the government created a forest observatory, an economic intelligence-gathering tool designed to support decision-making and supply reliable and relevant economic information on the industry. The government also initiated a program to share revenues from forestry and wildlife enterprises with communities. Revenues are deposited in a bank account opened in the Central Bank in the name of the communities, and are supervised by a technical committee comprising representatives of the ministries concerned (Interior, Finance and Budget, Water, Forests, Hunting and Fisheries) to help ensure transparent management of the revenues for the benefit of communities (GOCAR 2007, IMF 2009a, World Bank 2009c).

The Ministry of Water, Forests, Hunting and Fisheries (MEFCP) is working with the World Resources Institute (WRI) to improve the quality and availability of information on CAR’s forest sector and build the country’s remote sensing, GIS, and forest information management capacities.

DONOR INTERVENTIONS AND INVESTMENTS

USAID supports CARPE through the Biodiversity Support Program consortium. CARPE engages African NGOs, research and educational institutions, private-sector consultants, and governments in evaluating threats to the forests in the Congo Basin and identifies opportunities to manage the region’s forests sustainably. The European Commission supports programs such as the Ecosystèmes Forestiers de l’Afrique Centrale (ECOFAC) and the Avenir des Peuples des Forêts Tropicales (APFT), which are multi-disciplinary projects managed in large measure by anthropologists investigating and documenting the future of the peoples of the rainforest (CARPE 2001, APFT 2009).

The French Agency for Development (AFD) supports field offices of the MEFCP. The World Bank Projet de Gestion des Ressources Naturel (PGRN) project approved in 2018 also focuses on the forestry sector. The project’s first component aims at strengthening the fiscal and governance framework of the forest sector, and its second component supports local communities in planning and financing their development with forestry revenues and in part through the preparation of commune development plans.

Minerals

RESOURCE QUANTITY, QUALITY, USE AND DISTRIBUTION

CAR is rich in mineral resources, including diamonds, copper, gold, graphite, uranium, iron ore, tin, and quartz. As of 2020, only diamonds and gold were being developed, and production was mostly artisanal and small-scale. Several international companies from China, Russia, and elsewhere are engaged in gold and petroleum exploration. The mining sector accounted for 7% of GDP in 2007 but fell to only 3% in 2016 due mainly to the suspension of CAR’s legal exports of diamonds in 2013.

CAR is a member of the Kimberley Process Certification Scheme (KPCS). The KP was implemented to control the flow of rough diamonds into and within international markets and to combat the sale of “blood” or “conflict” diamonds, which were used to fund armed conflict and rebel activities. The KPCS requires the certification of all diamonds mined and also at the time of each transfer of ownership of the diamonds. CAR was suspended from the KPCS in 2013 due to the fall of the government and the lack of internal controls. In 2016 the KP adopted an Operational Framework for the Resumption of Rough Diamond Exports which created additional criteria to progressively allow exports from certain compliant zones. The USAID Property Rights and Artisanal Diamond Development (PRADD II) project assisted the CAR government to apply for and obtain permission to expand the number of compliant zones. However, rough diamond smuggling has become dominant with more than 95% of stones not accounted for in the legal chain of custody. The Ministry of Mines and Geology has put in place a roadmap to combat the illegal trade in diamonds (USAID 2019a).

LEGAL FRAMEWORK

The 2009 Mining Code, Loi n° 9-005 du 29 avril 2009, governs mining activities in CAR. Article 6 of the Mining Code provides that all mineral resources are the property of the state. Entities and individuals can obtain rights to CAR’s minerals while rights to minerals are separate and distinct from rights to land. The objective of the Mining Code is to promote and encourage research, exploitation, processing, and marketing of mineral resources for social and economic development. The Mining Code recognizes customary property rights and requires license holders to compensate holders of customary rights for damage to land or loss of land use resulting from mining operations (GOCAR Mining Code 2009).

Local customary tenure rights and rules, which govern much of the country’s agricultural and forest land, tend to be weak at mining sites along waterways. In the years following Independence, migrant miners claimed land along rivers for alluvial mining. In many areas that have been studied, the miners, who are known as chefs de chantier, did not seek rights through customary authorities. The miners claim rights based on their assertion of rights to unclaimed sites and use of the sites for mining. Most potential sites have been claimed, but where mining sites are unclaimed, the area is often considered open-access with rights available to those to assert their interest against outsiders and conduct traditional mining operations. Local governments, traditional authorities, and mining operators look to formal civil law to govern mining interests. Local government officials enforce the formal law, but chefs de chantier often do not know the legal requirements. Miners reported some knowledge of the need for artisanal licenses but had only limited (if any) knowledge of the Kimberley Process requirements for production logs and reporting; miners complain that government enforcement is arbitrary and self-serving.

TENURE ISSUES

The 2009 Mining Code regulates the mining sector through a system of permits and licenses. The rights granted are categorized as either industrial or artisanal. Individuals and entities can obtain one-year, renewable prospecting permits. Exploration permits are available for three years for areas up to 500 square kilometers, with two renewals. Mining licenses are granted to industrial miners for periods of up to 25 years, with renewals available for five years each until the deposit is exhausted. Licenses are obtained through application to the Minister of Mining and Geology, who (in conjunction with ministers responsible for environment, labor, territorial administration, and commerce and finance) provides a report to the Council of Ministers. The Council of Ministers issues a decree granting the license (GOCAR Mining Code 2009).

Under the 2009 Mining Code, mining companies are required to give the state a 15% share in any mining operation. Mining companies are also required to provide programs to employ and train CAR nationals in the industry, to assess potential social and environmental impacts of mining operations, and to develop and implement mitigation plans. The Code also requires mining companies to reach an agreement with landowners impacted by mining operations for compensation for loss of the use of land, with a forum for dispute resolution provided by the Ministry of Mining and Energy if parties are unable to reach agreement (IMF 2009b, GOCAR Mining Code 2009).

Artisanal mining licenses are available for periods of three years and are renewable for an additional three years. All artisanal miners must have valid permits to engage in artisanal mining. Artisanal miners must be CAR nationals, while no such restriction exists for industrial miners. All permits and licenses are subject to the terms and conditions established by the Ministry of Mining and Geology. The Ministry can terminate the permit and mining title for failure to abide by the terms of the contract or at the end of its period of validity (GOCAR Mining Code 2009).

The mining code also foresees the delineation of artisanal mining zones (ZEA) to facilitate the formalization of miners in areas not subject to industrial mining potential. ZEA have not been implemented until 2020 with support from the USAID Artisanal Mining and Property Rights (AMPR) project. Also, a special category of permits called semi-mechanized artisanal mining (PEASM) has become more popular in recent years with mining cooperatives, many working with foreign investors and mining labor, especially Chinese.

GOVERNMENT ADMINISTRATION AND INSTITUTIONS

The Ministry of Mines and Geology is responsible for the mineral sector. Exports of diamonds and gold is overseen by the Bureau of the Evaluation and Control of Diamonds and Gold (Bureau d’Evaluation et de Control de Diamant et d’Or) (BEDCOR). The General Direction of Mines and Geology (DGMG) oversees regional mining directors and sub-regional mining engineers, as well as technical directorates in charge of licensing, data management, and geological research.

The Kimberley Process Permanent Secretariat (SPPK) is the main entity in charge of implementing the KPCS in CAR. It is led by a Permanent Secretary and supported by local staff throughout the country called station chiefs (Chef d’antenne). The KPCS Operational Framework has put in place a national monitoring committee (CNS) and local monitoring committees (CLS) in each compliant or anticipated future compliant zone.

GOVERNMENT REFORMS, INTERVENTIONS AND INVESTMENTS

The government adopted the Mining Code in 2009 as part of its efforts to improve governance of the mining sector and encourage investment. The 2009 Mining Code establishes a system for granting and managing mining licenses that is more transparent and limits government discretion. The government has adopted a model contract that standardizes the terms of mining investments and facilitates the development of agreements between mining companies and local communities. The government is seeking to increase mining production and reduce the poverty rate of communities in mining areas by setting up a geological database; establishing an institutional framework and incentive-based regulations; encouraging transparent sector management; and developing small, medium, and large mining companies (IMF 2009b, GOCAR Mining Code 2009, GOCAR 2007). The 2009 mining code began a revision process in 2019 with African Development Bank (AfDB) and World Bank support.

The CAR government joined the Extractive Industry Transparency Initiative (EITI) in 2008, which was created to provide a foundation for improved governance in resource-rich countries through the verification and full publication of company payments and government revenues from oil, gas, and mining. CAR’s efforts to develop and strengthen its governance of the mining sector include establishing a national steering committee and multi-stakeholder group to provide oversight of the sector and engaging an independent director to collect and reconcile accounts (EITI 2009; IMF 2009b). However, CAR was suspended from EITI in 2013 due to political instability and has not yet been readmitted as of 2020.

DONOR INTERVENTIONS AND INVESTMENTS

USAID has supported good governance of the diamond sector since 2007, most recently with the 5-year Artisanal Mining and Property Rights (AMPR) project. The project began in 2018 and focuses on strengthening the capacity of GoCAR to implement the Kimberley Process Certification Scheme, improve social cohesion, and economic opportunity in artisanal diamond mining communities. USAID AMPR is also helping better understand the burgeoning gold sector in CAR.

In addition to USAID, the EU funds a similar project called the Governance Strengthening Programme in Artisanal Diamond and Gold Mining Sectors project (GODICA). The World Bank Projet de Gestion des Ressources Naturelles (PGRN) project also supports CAR’s mining sector in conjunction with the forestry sector. The project’s Component 3 aims at improving mining sector policies and Component 4 supports the formalization of the small-scale mining sector. The UNDP has also indicated intentions to start programming in the mining sector after completing a baseline study with UNICEF in 2018.