Introduction

Objectives

The Artisanal Mining and Property Rights (AMPR) project supports the USAID Land and Urban Office in improving land and resource governance and strengthening property rights for all members of society, especially women. Its specific purpose is to address land and resource governance challenges in the artisanal and small-scale mining (ASM) sector, using a multidisciplinary approach and incorporating appropriate and applicable evidence and tools. The project builds upon activities and lessons from the Property Rights and Artisanal Diamond Development (USAID PRADD) project in its first (2008-2013) and second (2014-2018) generation.

USAID AMPR is structured around four objectives:

- Objective 1: Assist the Government of the Central African Republic to improve compliance with Kimberley Process requirements to promote licit economic opportunities.

- Objective 2: Strengthen community resilience, social cohesion, and response to violent conflict in CAR.

- Objective 3: Increase awareness and understanding of the opportunities and challenges of establishing responsible gold supply chains in CAR.

- Objective 4: Improve USAID programming through increased understanding of linkages between ASM and key development issues.

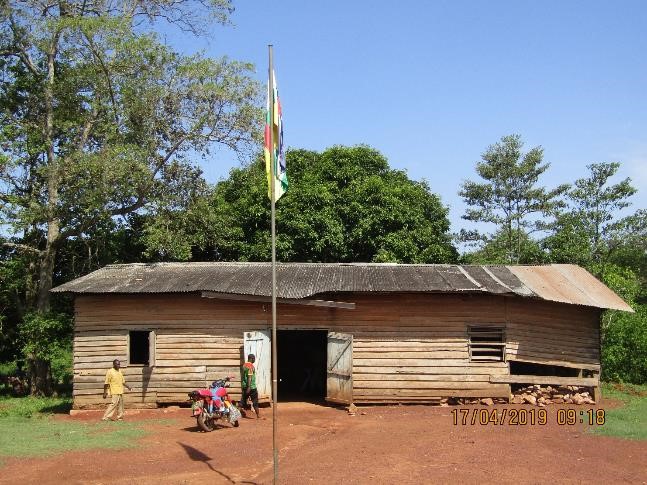

As part of the project’s component 1, AMPR Activity 1.2.3 intends to pilot a system for taxing diamond revenues for community development. This activity is based on the successful “SODEMI Model” that was supported by PRADD II in Cote d’Ivoire. Under this model, communities organized as cooperatives participate in mine site monitoring in exchange for taking a percentage of revenue for community-led infrastructure projects.

The central question guiding this research is to enquire whether a model that worked in northern Côte d’Ivoire might be transferred to the southwestern Central African Republic despite very different socio-economic contexts. With this objective in mind, this study first describes the core components of the “SODEMI” model, and second, from field information gathering analyzes how the local features of a few preselected southwestern Central African mining communities might respond to these core components from a socio-cultural and economic perspective. From the outset, the author did not expect to suggestion replication of the Ivoirian model, but rather to look at it for inspiration. This said, it is worth noting that in 2013 the Ivoirian diamond economy bore many traits that are common with the Central African economy today, including such features as the absence of a legal chain of custody; an embargo on diamond exports enforced by the Kimberley Process; a strong presence of illegal armed groups in the marketing system; and a contradiction whereby subsurface rights belong by law to the state while in practice these rights are also claimed by local communities.

Finally, it is important to stress that the spirit of the present study was more practical and programmatic than theoretical and legalistic. Its aim was not to design a model of local governance to reform the Central African legislation, but to propose a workable system to be piloted, as an experiment, in one of two local communities where the USAID AMPR project is expected to work in the years to come.

Background

The diamond economy in the Central African Republic has been experiencing an unprecedented crisis since the 2013 political and military crisis. Despite the election of a legitimate government in March 2016 and the redeployment of mining governance structures in the Western mining areas—Kimberley Process Permanent Secretariat, including KP Monitoring Committees or Comités Locaux de Suivi (CLS), Direction d’Appui à la Production Minière (DAPM) and Directions Régionales (DR)—the government does not have much control over the local dynamics of the diamond economy.

One of the dynamics leading to the diamond economy crisis is the sharp fall of artisanal production. Taking into account the official exports and the estimated level of smuggling before 2013, the total average production from 2000 to 2012 was 490,000 carats per year. Most recent studies estimated real production between 330,000 and 360,000 carats in 2018.[1] The number of active artisanal diamond miners (currently estimated at around 35,000 site managers and 270,000 mine diggers throughout the country) fell by one third. One of the direct reasons for this downward production spiral is the issue of pre-financing: only 20% of diamond producers and 50% of gold producers now receive financial support for production, compared with much higher percentages receiving pre-financing prior to 2013. In a local economy that is highly dependent on mining income, this trend presents a serious challenge to the survival and resilience of local communities.[2]

Another dynamic leading to the diamond economy crisis is the unprecedented level of smuggling. While the contraband of diamonds is estimated to have been about 20-40% of production between 1961 and 2012,[3] the illicit chain’s estimated proportion reached 82% of real production in 2017 and 96% in 2018. Good governance alone cannot address such a dramatic situation. Economically, it means that illegal smugglers are more powerful than legal exporters in the competition between the two supply chains. Politically, it creates a conundrum where every attempt to boost local production or to support mining communities in an economic context dominated by smuggling runs the risk of feeding the illegal chain even further.

Therefore, a successful model of decentralized governance of alluvial mining resources should not only seek to promote community development through community-led infrastructure and other local development projects, but also to boost local mineral production and to strengthen the legal chain of custody. The model should seek to support food security and community development, but also inadvertently contribute to smuggling. This perspective led to the following goals for the research:

- Design a system that promotes self-financing. At present, self-financing of artisanal miners seems like the only option given the decline of the traditional pre-financing and commercialization model.

- Design a system that ensures geographic traceability. While strengthening the legal chain clearly needs more than a governance system, an enabling environment based on geographic traceability would make it more difficult for mineral products registered at production to enter the illegal supply chain.

[1] Dewitt Chirico (2018) for USGS, Pennes (2018) for UNDP/UNICEF.

[2] The Southwestern mining communities are structurally more dependent on mining income than in other areas of the country: around 75% of the aggregate income of mining households comes from the mine.

[3] Doko Mazido Yélé (2011), World Bank (2008)