Overview

Burundi’s history of political conflict over the last 50 years has revolved in large measure around issues of access to land for agriculture. With a rapidly growing population of 8 million people overwhelmingly dependent on farming for employment and incomes, the ability of Burundi’s government to resolve outstanding disputes over rural land will be critical to political stability as well as economic growth. Repeated episodes of population displacements due to conflict, an already high level of population density, traditional laws and customs that discriminate against women’s ownership of land and other fixed assets, and the inter-linking of ethnic identities with access to land and other resources: all of these factors challenge the abilities of the government and its donor-partners to develop a satisfactory property rights regime and provide adequate resource governance in Burundi. Further, recent reports of increased investments in mining activities and the potential for petroleum extraction may generate new opportunities for conflict over natural resources.

Donors have stepped up their support for Burundi’s efforts to address land ownership and management issues since the election of 2005. Efforts have included: providing financial and technical assistance for drafting a new Land Code and for developing the dispute resolution work of the National Commission for Land and Other Possessions (CNTB); strengthening the capacity of the government to register property and of the judiciary and informal institutions to resolve disputes; piloting the decentralization of land administration to local levels (with specific priority given to ensuring that women had access to land); and developing options for repatriation and resettlement of displaced people and reintegration of former combatants into civilian life. Substantial and sustained economic growth based on increasing agricultural productivity will, however, require continued attention to issues of property rights and resource governance. Outstanding questions include, for example: how sufficient land might be made available to permit rural households, including those headed by women, to increase their incomes through intensified agricultural production; what kinds of rules would increase access to and assure better management of water and wetlands for production; and how forests might be maintained or even enhanced to protect watersheds and produce fuel wood and timber for the population.

Key Issues and Opportunities for Intervention

In order to realize stronger economic growth while maintaining peace and security, Burundi’s institutions for land administration, adjudication and dispute settlement, and the continued development of a new legal framework governing property rights will need substantial financial support as well as technical assistance. As a matter of priority, support might be targeted at:

Burundi is at a critical juncture regarding land access and tenure security. Reinvigoration of the Government’s effort to draft and pass a land code is a priority, followed by a long-term institutional and financial commitment from the international donor community. Once a land code passes, the GOB will need technical and financial assistance in drafting complementary legislation and implementing decrees, conducting a country-wide public information and awareness campaign to the population and civil society, training government administrative and judicial personnel on the law, and resolving land disputes that pre- date the code and/or those that arise due to new code provisions. The GOB will also need technical and financial assistance to build the capacity of new or newly reconfigured institutions charged with implementing different aspects of the law, particularly those related to land administration.

The work of the National Commission for Land and Other Property (CNTB) has already demonstrated some results but much remains to be done. Some have suggested that the traditional Bashingantahe’s capacities should be strengthened to permit disputes to be settled at the local level. In addition to providing financial support for the work of these organizations, donors could provide expanded training on conflict-resolution methods as well as helping them to ensure that the basic constitutional principles of equality and fairness are reflected in decision-making.

This is especially important for women being repatriated from camps of displaced persons and a relatively large population of widowed women, but is also important for ensuring that the principles of the Burundian constitution regarding individuals’ property rights are translated into reality. Donors have already begun to work with civil society organizations and have supported pilot efforts to reintegrate women into rural lives. Sustained support for expanded efforts is needed to have a greater impact.

There is growing evidence of excessive erosion in denuded watersheds, increased use of wetlands for production, and awareness that drought can threaten overall productivity. If Burundi’s nickel resources are exploited in the coming decade, these mining operations are also likely to have an impact on water use and quality. Donor support for assessing and reforming the existing institutional and legal frameworks governing water could held to ensure a more equitable and sustainable situation going forward. This initiative could also link with a forestry initiative, as protection of upper watersheds through afforestation is likely to be an important approach to better water management.

Summary

Since Burundi’s independence in 1962, ethnically based political parties have vied for control of the country, resulting in decades of violent conflict. Families have been forced to flee successive waves of conflict, and tens of thousands have been internally displaced or temporarily resettled in neighboring countries. Lands left by refugees and displaced persons have since been occupied by other families. As a result, rights for returnees are uncertain, and disputes are common. Continued risk of violent conflict in rural areas impedes development and hinders a reduction of government spending on security measures, to the detriment of pro-poor programs.

Since the 2005 elections and a 2006 ceasefire, a fragile peace has existed in Burundi. Some incidents of violence occur, such as in April 2008 when rebels fired on the capital, but sustained conflict has not resumed. In mid-2010, the national elections held in the country were marred by pre- election violence and resulting low turnout. The ruling party retained control of the country, and despite allegations by opposition parties of election abuses, international election observers concluded that the election procedures were transparent and conducted peacefully.

Burundi remains one of the poorest countries in the world, constrained by the productivity of its agricultural sector. Although its tea and coffee sectors have traditionally fueled Burundi’s exports, high – and growing – rural population densities have led to increased land scarcity, fragmentation and degradation, and these in turn have contributed to low levels of productivity in many parts of the sector that supports as much as 95% of the country’s population.

Burundi remains one of the poorest countries in the world, constrained by the productivity of its agricultural sector. Although its tea and coffee sectors have traditionally fueled Burundi’s exports, high – and growing – rural population densities have led to increased land scarcity, fragmentation and degradation, and these in turn have contributed to low levels of productivity in many parts of the sector that supports as much as 95% of the country’s population.

Much of Burundi’s forestland has been lost to the demand for fuelwood, and expansion of agricultural lands and plantations has replaced most natural forest. The country has had little experience with community forest management, although local communities have been engaged in plantation development. One of the largest remaining expanses of forestland is Kibira National Park which, together with Rwanda’s adjacent Nyungwe National Park, forms one of the greatest remaining tracts of mountain forest in East Africa and the most wildlife-rich ecosystem in the Albertine Rift.

Prior conflicts and lack of investment have damaged the country’s water supply facilities and reduced the government’s ability to provide safe drinking water to the population. In one study, 50% of respondents indicated that they have to pay bribes to obtain access to safe drinking water. The government recognizes the sector’s need for reform, and is working with USAID, the German Agency for Technical Cooperation (GTZ) and other donors on a new legal framework and restructuring plans.

Although historically Burundi has not been a globally significant source of minerals, it has substantial nickel reserves as well as stocks of other metals, and a British company has begun exploration of petroleum reserves under Lake Tanganyika.

Land

LAND USE

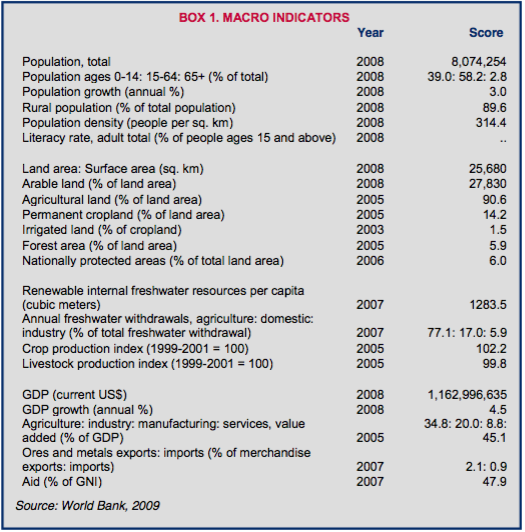

Burundi’s total land area is approximately 25,700 square kilometers, 91% of which is classified as agricultural land. As of 2007, 90% of Burundi’s 8 million people lived in rural areas. Burundi’s mild climate and adequate rainfall provide an environment suited to intensive agriculture. Cash crops include coffee, tea, cotton, tobacco, and sugarcane. Subsistence crops include bananas, maize, manioc, sweet potatoes, Irish potatoes, beans, peas, wheat, peanuts, vegetables, plantains, livestock, and fish. Ninety-four percent of Burundi’s working population is engaged in growing food crops (Banderembako 2006; World Bank 2009a; WFP 2010).

In spite of this emphasis on agriculture, Burundi’s population suffers from significant poverty and food insecurity. Approximately 67% of the population lives below the poverty line and many live in extreme poverty. Roughly 63% of the population suffers from food insecurity, although there is substantial regional variation. Burundi ranks 167th out of 177 countries on the 2007/2008 Human Development Index (World Bank 2008a).

Burundi’s 2008 GDP was US $1.1 billion, with 35% derived from agriculture, 20% from industry, and 45% from services (World Bank 2009a).

Burundi’s 2008 GDP was US $1.1 billion, with 35% derived from agriculture, 20% from industry, and 45% from services (World Bank 2009a).

LAND USE

With intensive use for production of food and some export crops, Burundi’s land resources are now characterized by significant land degradation, with soil erosion due to cultivation on steep slopes and degradation of watersheds. The heavy population pressure on the land has resulted in an average farm size of only 0.5 hectares, and even that area is, in many cases, fragmented. Little room for expansion remains; by some estimates, all land will be in use by 2020 (Hobbs and Knausenberger 2003; Theron 2009; Banderembako 2006; ARD 2008a; Encyclopedia of Nations 2010).

The overwhelming majority of Burundi’s cropland is rainfed; only 1.6% of all cropland is irrigated. For the year 2000, 51% of Burundi’s land area was in crops and 37% maintained in pasture (FAO 2007).

As of 2006, about 6% of Burundi was forested, and the annual rate of deforestation was 5.2% (2005) (World Bank 2009a).

LAND DISTRIBUTION

For Burundians, land is not only vital to their food security and livelihood – it is also a symbol of ethnic and family identity. In the precolonial era, the Burundian territory was ruled by a monarchy (a king, or mwami, and princes, or ganwa), under which there were largely autonomous and loyal chiefdoms. Those royal elite were the cattle-owning Tutsis, who comprised approximately 14% of the population. Hutus comprised 85% of the population and were primarily engaged in agriculture. The hunter-gatherer Batwa or Twa made up the remaining 1%. Designations of Hutu, Tutsi and Twa referred primarily to lineage and occupation, stratified along lines of wealth and sociopolitical standing. This social hierarchy also governed distribution of land based on a patron-client relationship. Conflicts among the ganwa eventually transformed these relationships into more feudal-like arrangements with Tutsis as overlords and Hutus reduced to serfs (IDMC 2008; EISA 2010).

Over the past fifty years, however, the distribution of land among various groups has been altered as Hutu- dominated parties have challenged Tutsi authority. The ensuing violence has forced Tutsi families to flee, and Hutu families have claimed their lands. Destruction of natural forestlands reduced the land available to the Twa who have, as a consequence, become further marginalized economically. Further, Burundi’s population has increased by a factor of four, and landholdings have been divided to accommodate claims of sons for family land. The population density in Burundi is now among the highest in Africa, at 300 inhabitants per square kilometer, and the farm population density is even higher – at 640 inhabitants per square kilometer. The average size of family farms is less than 0.5 hectares and divided up among two to four parcels (Banderembako 2006; ARD 2008a; World Bank 2008a).

The return of nearly 500,000 refugees primarily from neighboring Tanzania has increased the pressure on Burundi’s land. Approximately 15% of Burundians are now landless, many of whom were displaced by conflict and have not returned to their homes or have returned to find their land occupied. Eighty percent of persons displaced by conflict are landless. Among the minority Twa population, at least half are landless, having been forced out of the forests they depended on for their livelihoods and not been able to secure other land (Jackson 2003; Kamungi 2005 et al.; Amani 2009; IDMC 2008; UNHCR 2009).

LEGAL FRAMEWORK

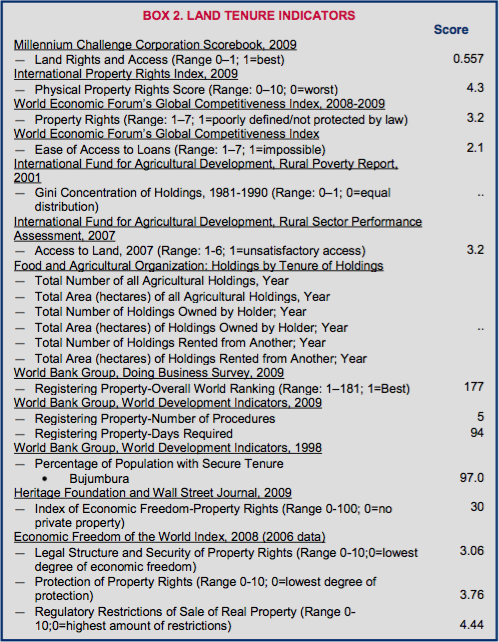

The Post-Transition Interim Constitution of the Republic of Burundi, ratified by popular vote in 2005, guarantees every Burundian the right to property. Specific legislation and policy with regard to land, however, do not support this constitutional right. The Constitution grants foreigners equal protections to person and property, without restrictions on foreign ownership of land (GOB Constitution 1992a; USDOS 2009).

The 1986 Land Code and the customary tenure system provide parallel structures for governing access to land. The goal of the Land Code was to encourage the country’s development and increase agricultural production, while the customary system provides for local administration of lands. However, the Land Code recognizes customary rights to land, including fallow land. Under the customary, community-based system, land is held by individual heads of households. The Code, by contrast, requires that land held customarily be registered in order to be officially recognized. The registration process, however, is extremely complex and infrequently followed. The result is that community-based tenure systems have a quasi-legal status, but are not formally recognized (Leisz 1996).

At the conclusion of the civil war, the Arusha Agreement on Peace and Reconciliation in Burundi (2000) called for revision of the 1986 Land Code to resolve unspecified land management problems. Article IV of the Accords promises that returning refugees will be able to access their land or will receive adequate compensation (GOB Constitution 1992a; Kamungi et al. 2005; Leisz 1996).

After several years of starts and stops, in 2008 the GOB made significant progress on three land-related fronts. First, initiated by an inter-ministerial technical committee, the GOB adopted a National Land Policy Letter, which identifies four government priorities: (1) amendment of land legislation and modernization of land administration services; (2) restructuring and modernization of administrative bodies responsible for land management; (3) decentralization of land administration; and (4) inventory of state lands (Freudenberger and Espinosa 2008; Freudenberger 2010, pers. comm.).

Second, in 2008, the GOB held public consultations on land tenure issues and revised the Land Code with assistance from USAID and the European Union (EU). Issues addressed included: revocation of governors’ authority to allocate state land (only the central Ministry of Environment would hold such authority); ownership and management of marshlands; and rights to lands of 1972 refugees (but apparently not to lands of 1993 refugees). The draft Code makes no reference to land rights of women and girls. The GOB sent the draft to Parliament for a vote in spring 2009, but withdrew it in spring 2010, without a vote, just prior to elections (Freudenberger and Espinosa 2008).

Third, the GOB adopted a Five-Year Action Plan to Implement the Land Code. The GOB estimates that implementation of the new code will cost US $17–20 million. The prospects for adoption of the draft land code and action plan for implementation are uncertain (Freudenberger and Espinosa 2008).

TENURE TYPES

Burundi’s formal law recognizes state and private land. State land includes land classified as public land (e.g., rivers, lakes) and private state land, which includes all state land not classified as public, including vacant land, forests, land expropriated for public use, and land purchased by the state. Under the law, all land that is not occupied is considered state land. Temporary rights of occupation are available on land classified as private state land (GOB Land Code 1986).

The 1986 Land Code recognizes private rights to land. Landowners have the right to exclusive use and possession, the right to transfer land freely, and the right to mortgage their land. The Land Code permits usufruct rights, leaseholds, and concessions. Under the 1986 Land Code, rights over previously titled land are recognized as private property rights. The 1986 Land Code expressly recognizes the legitimacy of land rights acquired and held under customary law. However, all asserted rights must be registered; unregistered customary rights do not have the protection of the formal law (GOB Land Code 1986; Leisz 1996).

Under customary law, land in Burundi is generally held individually, rather than by lineage. Families obtained land through clearing and using the land or purchasing land. Wealthier individuals may also own rights to pastureland and forest areas. Access to the forest and grazing land is generally shared with neighbors and relatives, who are permitted to use the land for grazing and collection of forest products. Historically, customary law recognized tree tenure separate from land tenure: the person planting trees had the right to benefit from the production, regardless of land ownership. It is unknown whether separate tree and land tenure continues to be recognized (Leisz 1998).

SECURING LAND RIGHTS

Rights to land are acquired by inheritance (males only), purchase, donation, lease, and government allocation. There are five steps to register the sale of land: (1) parties obtain proof of title at the Land Registry; (2) parties engage a lawyer to draft the sale agreement, and each party signs; (3) buyer checks the price at the land registry; (4) the Public Notary notarizes the sale agreement; and (5) parties file for a name change with the Land Registry. The registration process requires an average of 94 days and payment of 6.3% of the property value in fees. The process is not widely used, leaving the recognition and security of informal rights in question (World Bank 2008b; Leisz 1996).

By law, transfers of land, including via purchase and inheritance, must be registered. In reality, registration is extremely rare; less than 5% of all land is registered. Instead, ownership is informally recognized based on oral testimony. Even where title deeds have been issued, they are of limited value. In 2008 there were five governmental agencies issuing documents (certificates or titles), formalizing rights to land with little coordination among them, and reports of corruption within the Ministry of Lands. It is, therefore, not uncommon for two documents issued by different agencies to address the same parcel. Under these circumstances, confusion over the legitimacy of documents – and hence legitimacy of ownership claims – is common (Kamungi et al. 2004; Kamungi et al. 2005; ARD 2008a).

Burundi’s unique history of periodic violent conflict accompanied by large population displacements has also made the security of land rights problematic. When families have been forced to flee successive waves of conflict, others have come forward to claim and occupy their land. The 1986 Land Code has been used to settle rights in favor of some occupants who have been on the land at least 30 years, while denying rights of refugees from 1972–1973 to return to their land. When the displaced families have returned, it has not always been possible to present claims strong enough to support the eviction of the replacement families, even when there is some residual memory among community members of the original land rights. The result is that rights to land have become highly uncertain for millions of Burundians, and disputes are common. Creative approaches to provide land for returnees have been developed (e.g., peace villages) but there is reportedly some dissatisfaction with these solutions (ARD 2008a; Theron 2009).

Land access and tenure security have long been on the country’s political agenda, and a new land code has been under consideration for years. The prospect for progress in the near future is unknown. The 2010 national elections resulted in the ruling party retaining control of the country (IFES 2010a; IFES 2010b; EAC 2010).

INTRA-HOUSEHOLD RIGHTS TO LAND AND GENDER DIFFERENCES

Both custom and law restrict women’s access, use and ownership of land. Burundi’s patriarchal customs and the patrilineal inheritance system operate to prevent women from owning and inheriting land. Women must rely on relationships with male relatives to secure access. Given the extreme and pervasive poverty in Burundi, particularly among women, the chances of a woman purchasing a parcel of land during her lifetime are slim (Kamungi et al. 2005).

Both custom and law restrict women’s access, use and ownership of land. Burundi’s patriarchal customs and the patrilineal inheritance system operate to prevent women from owning and inheriting land. Women must rely on relationships with male relatives to secure access. Given the extreme and pervasive poverty in Burundi, particularly among women, the chances of a woman purchasing a parcel of land during her lifetime are slim (Kamungi et al. 2005).

Burundi’s Constitution provides that every person has the right to property, guarantees equal rights and equal protection to all Burundians regardless of sex, and prohibits discrimination based on sex. The Constitution recognizes Burundi’s adoption and ratification of the Convention on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women (GOB Constitution 1992a; ARD 2008b).

Article 122 of Burundi’s Code of Persons and Family, as amended in 1993, provides that the male is the head of household. The Code includes the right to joint management of family property. If a husband is absent, the wife has management rights. In practice, men who will be absent tend to delegate land matters to their male relatives. The Code prohibits polygamy, although the custom is still practiced (Kamungi et al. 2005; UNHCR 2001).

Burundi’s formal law grants wives and daughters no right to inherit land. Because daughters leave home at marriage, custom dictates that sons inherit in order to keep the land within the family. Daughters inherit only if there is no male descendent. An unmarried daughter may remain in her natal home and cultivate the land that is not needed by her brothers. Upon her parent’s death, an unmarried daughter’s access depends upon the good will of her brother (Sabimbona 2001; ARD 2008b).

Over 25% of Burundian women are widows. Although customary law traditionally grants widows a lifetime use-right, that custom is fading given increasing land pressures by a growing population. If in-laws permit a widow to stay on the land, she has no right to sell the land. Widows who are permitted to use in-law family land are vulnerable to land-grabbing by male relatives of the deceased husband, and a childless widow has no rights to use her husband’s land. A divorced woman has no right to the land (Kamungi et al. 2005; ARD 2008b; van Leeuwen and Haartsen 2005).

In Burundi’s conflict and post-conflict environment, women’s access to land is further compromised by repeated displacement. Forty-four percent of displaced households are headed by women and are trying to obtain access to land in a country where searching for land is considered a man’s domain. Many of those households are likely to remain landless (Sabimbona 2001).

A draft law reforming Burundi’s inheritance and marital property regimes was submitted to the Cabinet in 2006, where it languished for years. The Cabinet considered inheritance rights for women a sensitive and potentially divisive issue and made the unusual request for a national consultation before passage of the draft law. In 2008, several NGOs were successful in convincing the GOB to remove the consultation requirement and return the draft law to the Cabinet for consideration (ARD 2008b; Global Rights 2009).

LAND ADMINISTRATION AND INSTITUTIONS

Land administration in Burundi is spread across several ministries competing for authority. The Office of Titles and Registration is within the Ministry of Justice. As of March 2008, the Office of Land Use Planning, Cadastre, and Urban Planning was within the Ministry of Environment, Management, and Public Works. Whether that Office shifted into the new Ministry of Environment and Territorial Planning in 2008 is unclear. The Ministry of Agriculture is involved in land-use planning, and the Ministry of Home Affairs is responsible for local administration of state, public, and private land (Freudenberger and Espinosa 2008; ARD 2008a).

Established in 2006 under the Office of the First Vice President, the National Commission for Land and Other Properties (CNTB) operates at the national, provincial, and communal levels. The CNTB has the authority to resolve land disputes, assist vulnerable people to reclaim their land or obtain compensation, and update the inventory of state-owned lands. In part due to its limited funds relative to need, the CNTB is facing challenges in fulfilling its mandate (Theron 2009).

At least five agencies in Burundi are issuing documentation (titles or certificates) for the formalization of land rights. There is little coordination, however, and there is evidence that competing documentation exists for the same piece of land. This ambiguity leads to a great deal of confusion over the legitimacy of documents in the event of transactions or disputes, and in the securing of credit (ARD 2008a).

Some customary institutions in Burundi, such as the village-level system of dispute resolution known as the Bashingantahe, continue to have a significant role in local land issues (Theron 2009).

LAND MARKETS AND INVESTMENTS

Most of Burundi’s land changes hands on the informal market. In urban areas, most land in established settlements is owned by the state, with residents holding occupancy rights under formal law. Squatters and residents of most informal settlements usually have no rights recognized under formal law but have rights of occupancy under customary law. In the late 1980’s, the urban land market in Burundi was active; both holders of formal and informal occupancy rights and private landholders sold or leased their plots, usually for cash. In some cases the transactions were recording with the municipality, but frequently the transactions were conducted informally (Dickerman 1980).

Land and buildings are the dominant form of security on commercial loans, although lack of clear title for most parcels means that only a small minority of land is available for mortgaging. (About 80% of parcels outside large towns lack clear title.) Such loans tend to be over-secured because foreclosures are difficult to execute, and banks have a limited ability to assess land value (USAID 2008b).

In rural areas, land transactions appear to be relatively frequent as displaced people and refugees return to land, and households seek more land to farm. Land rights are often disputed, and fraudulent transactions, including multiple sales or leases of the same property, are a common cause of conflict (Kamungi et al. 2004).

COMPULSORY ACQUISITION OF PRIVATE PROPERTY RIGHTS BY GOVERNMENT

Burundi’s Constitution provides that no person shall be deprived of his property except for reasons of public utility or for exceptional and state-approved reasons. The state is required to pay just and prior compensation to landholders. Articles 407–433 of the 1986 Land Code provide procedures for expropriation of land, including declarations of public utility and requirements of public notice. Under the Land Code, the provincial governor must approve of any expropriation of 4 hectares or less of rural land; expropriations larger than 4 hectares require the approval of the Minister of Agriculture. The Minister of Urbanism must approve of urban land expropriations up to 10 hectares. Larger land expropriations require a decree (GOB Constitution 1992a, Art. 36; GOB Land Code 1986).

Abuse of the power of expropriation is common, with expropriated land often allocated to influential political and military elites without adequate compensation being paid to the landowners. Local authorities commonly make decisions about the justness of an expropriation and compensation due based on a mix of statutory and customary law, and their interpretations of both vary widely across provinces (Jooma 2005; Kamungi et al. 2004; USDOS 2009).

LAND DISPUTES AND CONFLICTS

Land disputes are common in Burundi and are often violent. Land rights, particularly access to land for certain groups, were a contributing factor to the ethnically based civil war. An estimated 90% of all court cases are related to land rights, and 60% of all crimes are linked to land. Disputes occur over claims of ownership and boundaries and are often within families and exacerbated by the waves of displacement and return that took place in response to periods of violent conflicts. Other common causes of disputes are: competing claims of inheritance (including by orphans); expropriation of land; polygamous marriages; and fraudulent land transactions (Theron 2009; World Bank 2008a; Kamungi et al. 2005; ARD 2008a; van Leeuwen and Haartsen 2005).

Land-related disputes are brought before the customary institution (the Bashingantahe), the formal court system, or pursued informally with local authorities or NGOs. Disputes related to repatriation of refugees and internally displaced persons (IDPs) may also be resolved by the administrative body, the National Commission for Land and Other Properties (CNTB). A study in nine provinces found that over half of those people with land disputes who sought outside assistance to resolve their claims brought them to the Bashingantahe (Kamungi et al. 2005; Theron 2009; van Leeuwen and Haartsen 2005).

The traditional Bashingantahe is an organized, village-level body of wise men (i.e., known for being true, just, and responsible) that resolves various types of disputes, including those related to land. Decisions of the Bashingantahe are not legally binding. Enforcement of such decisions is difficult, particularly when the decisions conflict with customary practice or where a ruling favors an orphan or widow. Traditionally a male-dominated institution, the Bashingantahe now includes at least a few women members with decision-making authority. Over years of conflict and political crises, the legitimacy of the Bashingantahe has deteriorated, and there is some evidence of problems with bias and corruption, but the system has survived (Theron 2009; ARD 2008b).

Resolution of a land dispute within the formal court system is procedurally difficult and a lengthy process. At the lowest level, magistrates have little education and training. The courts have limited budgets, including no funds for field visits, and enforcement of judgments is uncertain. Corruption is an issue, in part due to low judicial salaries. Above the lowest level, there is a perception that the court system is Tutsi-dominated and so few Hutus use the court system to pursue justice (Kamungi et al. 2005; van Leeuwen and Haartsen 2005).

KEY LAND ISSUES AND GOVERNMENT INTERVENTIONS

The Ministry of Environment and Territorial Planning is promoting the strengthening of national, provincial, and local land-use planning. The government works closely with the World Bank and EU to prioritize development interventions, especially on state lands (Freudenberger and Espinosa 2008).

DONOR INTERVENTIONS

There has been significant donor investment in the land sector in partnership with the GOB, primarily related to land law and administration and less so related to land issues of returning refugees and IDPs. USAID, through the Burundi Policy Reform Program, and the EU, through the Good Governance (Gutwara Neza) project, provided legal drafting assistance to the interministerial committee on revising the draft Land Code, the National Land Policy Letter, the Five-Year Action Plan, and a country-wide public consultation. USAID also has provided comments on the draft Inheritance Law. The EU’s Gutwara Neza project conducted a land offices (guichets fanciers) pilot in two provinces (Freudenberger and Espinosa 2008).

The Swiss launched a three-year pilot program of decentralized land management in two communes in the province of Ngozi. As of 2009, the Belgian development agency will support local community planning and rural development in one province. As part of that project, the Belgians will support land formalization and registration of public and private lands. The GOB and the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) have been working closely to develop a strategy to settle returning refugees, resulting in the creation of Peace Villages or integrated village development for returnees (Freudenberger and Espinosa 2008).

Several donors are investing in improving the capacity of the Bashingantahe, including the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). There are a number of NGOs providing assistance to community members in resolving land disputes, including The African Centre for the Constructive Resolution of Disputes (ACCORD), Advocats Sans Frontières, the Burundi Women Lawyers Organization, and the Norwegian Refugee Council. Despite their efforts, demand far outweighs supply (Theron 2009).

Freshwater (Lakes, Rivers, Groundwater)

RESOURCE QUANTITY, QUALITY, USE AND DISTRIBUTION

Burundi straddles the Nile and Congo basins and has abundant groundwater and freshwater resources. The country has three large lakes, including Lake Tanganyika (one of the world’s largest freshwater lakes) and significant wetlands and marshland. Most of the country receives between 1300–1600 millimeters of rainfall per year, with the wettest areas in the northwest (Hobbs and Knausenberger 2003; Banderembako 2006; World Bank 2008a; GIEWS 2010).

Despite these significant resources, access to water in Burundi has been challenged: the country experienced several droughts between 2004 and 2006; marshes and wetlands have been drained or used seasonally for agricultural production; and infrastructure for water delivery fell into serious disrepair or was destroyed during the conflicts in the 1990s and early 2000s. Urban water supply in Burundi dropped from over 70% coverage in 1993 to 60% coverage in 2008. In rural areas, 40% of the population has access to safe drinking water. In a World Bank Institute study, 50% of respondents reported paying bribes to obtain access to safe drinking water. Between 66% and 78% of all reported illnesses are the result of lack of access to safe drinking water and sanitation (Hobbs and Knausenberger 2003; Banderembako 2006; World Bank 2008a).

Water use in Burundi is shared by the following sectors: agriculture (77%), domestic (17%), and industry (6%). Irrigation is limited to surface irrigation (ponds, ditches, and furrows) and is poorly developed (FAO 2007; FAO 2005).

With limited mechanisms for erosion control, rainwater is accelerating land degradation in Burundi. Sedimentation in waterways, wetlands, inland lakes, and Lake Tanganyika is causing loss of fish and wildlife habitat, filling channels and lakes, and spreading pollutants (Banderembako 2006; USFS 2006).

LEGAL FRAMEWORK

Burundi’s 1992 Water Code, (Décret n° 1/ 41 du 26 novembre 1992 portant institution et organization du domain public hydraulique), currently under revision, governs the country’s water resources. Burundi’s water is within the public domain, and the Water Code governs rights of access to groundwater, lakes and water courses, as well as the distribution of drinking water. The Code includes provisions that were designed to: (1) ensure conservation of water and protection of aquatic ecosystems; (2) supply drinking water to the population and protect water resources from pollution; and (3) develop water as an economic good and respond to the water needs of all sectors of the national economy. Order in Council No. 1/196 of 2 October 1968 gave the public utility for water and electricity (REGIDESO, Régie de Production et de Distribution de l’Eau et de l’Electricité) a monopoly over water catchment and distribution, and Decree No. 100/072 of 21 April 1997 delineated responsibilities for water distribution and management between the Directorate General of Rural Water and Electricity (DGHER) and REGIDESO (GOB Water Code 1992b; ADF 2005).

In 2000, Burundi adopted Law No. 1/014, which sets out a framework to support private sector engagement in the provision of drinking water and energy, including a regulatory body and development fund. Law No. 1/014 also eliminated REGIDESO’s monopoly over the provision of drinking water and energy and provided that REGIDESO and DGHER are delegated public service providers operating under a to-be-established regulatory body. Order in Council No. 1/011 of 8 April 1989 reorganized municipal administration, and the GOB transferred some functions relating to management and maintenance of water and sanitation infrastructure to the communes (ADF 2005).

Other laws governing Burundi’s water resources include: (1) the Environment Code (Law No. 1/010 of 30 June 2000), which addresses issues of water resources management and conservation and the development and protection of watersheds and land; and (2) the Public Health Code (Order in Council No. 1/16 of 17 May 1982), which requires that all projects relating to water catchment have the prior authorization of the Minister in charge of health (ADF 2005).

MWEM’s Water Sector Policy (2005–2007) expresses the government’s commitment to ensuring the quality and quantity of water needed to meet the demands of the different users. The policy goals are to: (1) improve knowledge of water sources for efficient, equitable, and sustainable management of water resources; (2) increase the water and sanitation coverage; and (3) achieve better coordination among sector players (ADF 2005).

TENURE ISSUES

Burundi’s 1986 Land Code provides that the state owns Burundi’s rivers, lakes, and water resources. The 1992 Water Code provides that, with the exception of domestic use (including water for livestock and gardens), all water access requires a specific authorization or government concession. Regulations govern the conditions of extraction of water from groundwater sources or surface water sources for plantation development, irrigation, or other non-domestic uses. All rights granted are subject to the terms of these regulations, are temporary, and are revocable. All water users are required to use water resources in a manner that avoids pollution and the spread of waterborne disease (GOB Land Code 1986; GOB Water Code 1992b).

The 1992 Water Code provides for the establishment of Water User Associations, which, once properly constituted, can obtain authority for management of water resources at local levels (GOB Water Code 1992b).

GOVERNMENT ADMINISTRATION AND INSTITUTIONS

A number of institutions are involved in the management of water resources, resulting in overlapping responsibilities in some areas. The Ministry of Water, Energy and Mines (MWEM) leads policy formulation through the Directorate General for Water and Energy. Under MWEM, REGIDESO is responsible for catchment, treatment and distribution of drinking water in urban and urbanizing centers. The Directorate General of Rural Water and Electricity (DGHER) oversees and coordinates access to drinking water in rural areas, with some authority passed to 34 communal water authorities (RCEs). Water User Associations are responsible for maintaining local water points (UN-Habitat 2007; USAID 2008a; ADF 2005).

The establishment of the Communal Water Authorities coincided with the 1993 outbreak of violence in Burundi. Infrastructure was destroyed, RCEs lack management capacity, and few users paid water rates. In 2005, only 16 of 34 communes had operational RCEs, and only about half of those were able to collect water rates. Authority was transferred to the municipal level, but with no better results overall. Donors have been supporting efforts to revitalize the RCEs on a pilot basis as privately managed nonprofit organizations, with some promising results (ADF 2005).

GOVERNMENT REFORMS, INTERVENTIONS AND INVESTMENTS

With the support of USAID’s Burundi Policy Reform initiative, in January 2010 the Ministry of Water, Environment, Spatial Planning and Urban Development organized a workshop consultation on the draft revision of the 1992 Water Code. The ministry noted that the sector suffers from lack of appropriate standards, lack of coordination, unclear delineation of responsibilities among various government bodies, and poorly developed and managed data and information. As a result the country does not have sound management of its water resources. USAID expressed its commitment to working with the government to develop a legal framework governing the country’s water resources (GOB 2010b).

Under its National Water Master Plan, the GOB is working to improve management of watersheds in order to protect water sources and increase the domestic water supply. The GOB’s objectives for the water sector are to identify efficient and equitable means of meeting demands for potable water and other uses, to improve the availability of water at an affordable price, to coordinate sectoral interests, and to achieve optimal use of water to support sustainable development. The Government’s objective in the rural sector is to be able to provide a water source within less than a 500-meter radius of each household between now and 2015. To that end, the government identified the following areas for attention: (1) rehabilitation and development of water sources and water supply networks; (2) strengthening of water production plants; (3) and improving the capacities of existing Communal Water Authorities (ADF 2005).

DONOR INTERVENTIONS AND INVESTMENTS

In FY2009, the USAID-sponsored Burundi Policy Reform Program shifted its focus from the land sector to water resources management (among other foci) in recognition of the political support behind water reforms. USAID has been providing technical and financial support to assist the government in developing a new legal framework for the water sector, including organizing consultations with local government, communities, and civil society organizations and convening the stakeholders workshop in January 2010 to work on revisions to the 1992 Water Code (GOB 2010b; USAID 2009).

GTZ has been one of the largest donors to Burundi’s water sector and plays a lead role in coordinating donor activities. In partnership with the Ministry of Water, Energy and Mines and other ministries, GTZ is implementing a major water and sanitation program in three rural areas, funded by KfW Entwicklungsbank (KfW Development Bank). GTZ is also working on the development of guiding principles for a new water policy and supporting legal framework (GTZ n.d.; USAID 2009).

The World Bank’s US $50 million Multi-Sectoral Water and Electricity project (2008–2013) was designed to: (1) increase access to water supply services in peri-urban areas of Bujumbura; (2) increase the reliability and quality of electricity services; (3) increase the quality and reliability of water supply services, with primary focus on Bujumbura; and (4) strengthen the public utility (REGIDESO)’s financial sustainability. The FY2009 Statement of Project Execution (SOPE) reports that due to delays in the processing of procurements, no reportable progress was made in FY2009 (World Bank 2009b).

Other donors involved in the water sector include the African Development Bank (ADB), for rehabilitation and development of urban services and integration of water management; the EU, for rural and peri-urban water infrastructure development and capacity-building; the Austrian Cooperation, for water resources management and planning; and the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), for hygiene and sanitation awareness and capacity-building of rural drinking water and sanitation facilities. As part of its Lake Victoria Region Water and Sanitation Initiative, UN-Habitat proposed significant reforms for the water and sanitation sector, including piloting those reforms in three rural areas (USAID 2008a; UN-Habitat 2007).

Trees and Forests

RESOURCE QUANTITY, QUALITY, USE AND DISTRIBUTION

About 6% of Burundi’s total land (152,000 hectares) is forest, only 14% of which is natural forest. The balance is plantation forest, which has been expanding since 2000 in an effort to meet the needs of the population for fuelwood and timber and to restore tree cover. Most of the country’s remaining natural forest is found along the Congo-Nile ridge, which has dense montane forests in the highlands and xerophilous vegetation on the summits. The western plains have some original savanna forests and semi-deciduous forests along Lake Tanganyika and in the southern region, a nature reserve protects 3000 hectares of primarily montane forest (Athman et al. 2006; Koyo 2004).

Protected areas cover 4.5% of the total land and include national parks, reserves, and protected landscapes, which are forested tracts intermixed with agricultural land. The country’s largest national park, Ruvubu, covers 50,800 hectares in the northeastern part of the country and includes tree savanna, open forests, gallery forests, and swamps. The mountainous Kibira National Park spans 40,000 hectares in northwestern Burundi and is the source of two-thirds of Burundi’s water. Half of Burundi’s hydroelectric energy is produced by the park’s dam. Together with Nyungwe National Park across the border in Rwanda, Kibira is the largest remaining tract of mountain forest in East Africa and considered the most wildlife-rich ecosystem in the Albertine Rift (a network of valleys in Burundi, Rwanda, Tanzania, Uganda, and the Democratic Republic of Congo). The Kibira National Park is home to 98 species of mammals, including rare owl-faced monkeys, 200 species of birds, and 644 plant species (Nzojibwami 2003; IRIN 2002).

The Batwa (also known as the Twa or pygmies) are Burundi’s forest people, hunter-gatherers who traditionally lived in small groups and depended on the forests for their livelihoods. Between 40,000 and 80,000 Batwa live in Burundi, mostly in extreme poverty. The Batwa’s historical occupancy of the forests did not confer formal, statutory rights to the land, and as incompatible uses were introduced into forested areas (such as farming, wildlife conservation, agribusiness, and pasture) the Batwa were forced from the land. Almost all Batwa are landless (Amani 2009; FPP 2008; Jackson 2003).

Burundi has had one of the world’s highest rates of deforestation, since colonial times losing forests covering about 34% of total land area. The forests have provided wood for fuel, charcoal-making, furniture and construction, and land for cultivation. During the war, combatants often sought refuge in the forests, and opposing forces set fires and destroyed resources to expose enemy locations. Following the war, the return of refugees and IDPs has resulted in small-scale clearing for fuelwood. Between 2000 and 2005, deforestation occurred at an annual rate of 5.2% (Hobbs and Knausenberger 2003; USFS 2006; World Bank 2008a; Athman et al. 2006).

LEGAL FRAMEWORK

The 1985 Forestry Code (Act No. 1/02 of 25 March 1985) and directives under that Code govern the types, allocation, and use of forestry resources. Decree No. 100/47 of 3 March 1980 established the National Institute for Nature Conservation and Environment (INECN), taking its current name in 1989 (by Decree No. 100/188 of 5 October 1989) (FAO 2010; Koyo 2004; Leisz 1996; Hobbs and Knausenberger 2003).

Burundi’s forest policy dates from 1999 and is contained in the Ministry of Land Planning and the Environment’s sectoral policy. The policy framework calls for: revisions to the legal framework governing forests; development of agroforestry; strengthening of forest management; protection of natural ecosystems; development of information systems to monitor natural resources; and capacity-building for forest personnel. Most of the efforts to implement forest policy have related to the development of agroforestry and plantations for reforestation and to provide wood for energy (Koyo 2004; FAO 2010).

TENURE ISSUES

Under formal law, forestland and forest resources are owned by the state, communes (local authorities), or private individuals. The Forest Code governs all forests, regardless of ownership, and sets various restrictions on forest use. The Forest Code bans clearing in state forests and afforested areas and sets rules for clearing on communal and private forestland. Burning crop residues, grazing land, and other agricultural practices are restricted, and the forest service has authority to impose penalties for noncompliance. However, in most areas of the country, the Forest Code is not enforced: the population‘s dependence on forest resources for livelihoods is great, and the forest service lacks human and financial capacity to enforce the restrictions on access and use (USFS 2006; Hobbs and Knausenberger 2003; Koyo 2004).

State forests include natural forests, which are inalienable and within either national parks or protected forest reserves. State plantations are usually 10 or more hectares, while communal plantations, which are managed by local communal authorities, are less than 10 hectares. Protected landscapes are areas that have integrated state forestland (primarily plantations) with private agricultural and forestland in an effort to encourage local residents to protect the forests. Harvesting of plantation trees is by permit. Management of state and communal plantations and protected landscapes has been haphazard. The need for fuelwood, access to agricultural land, and timber for construction has resulted in the loss of many plantations (Leisz 1996; Hobbs and Knausenberger 2003; Koyo 2004; Athman et al. 2006).

Private forests are usually managed as micro-plantations devoted to agroforestry. These plantations incorporate trees into other rural activities and raising of livestock (Koyo 2004).

GOVERNMENT ADMINISTRATION AND INSTITUTIONS

The Ministry of Water, Environment, Territory Management and Urbanism has responsibility for the country’s forests. The ministry, which was reorganized and includes the former Ministry of Territory Management and Environment, includes the Department of Forestry, which has primary responsibility for plantation forests outside protected areas. The National Institute for the Environment and Conservation of Nature (INECN) has management responsibility for Burundi’s natural forests, national forest reserves, and plantations within protected areas (GOB 2010a; ERA 2009; Hobbs and Knausenberger 2003).

Burundi has limited government capacity to manage its forests or undertake forest-related programs. In most areas, the country’s national forests are subject to unrestricted illegal harvesting, clearing for agriculture, and collection of fuelwood. The government has engaged local communities in plantation projects, but results have been mixed, with economic pressures on the population often overwhelming the government’s capacity to manage sustainable-use programs (Koyo 2004; Banderembako 2006).

GOVERNMENT REFORMS, INTERVENTIONS AND INVESTMENTS

Along with Cameroon, the Central African Republic, the Republic of the Congo, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Gabon, Equatorial Guinea, Chad, São Tome/Príncipe, and Rwanda, Burundi is a member of the Central African Forests Commission (COMIFAC). COMIFAC is the primary authority for decision-making and coordination of subregional actions and initiatives pertaining to the conservation and sustainable management of the Congo Basin forests. COMIFAC was established in 1999 with the signing of the Yaoundé Declaration, which recognizes the protection of the Congo Basin’s ecosystems as an integral component of the development process and reaffirms the signatories’ commitments to work cooperatively to promote the sustainable use of the Congo ecosystem in accordance with their social, economic, and environmental agendas. COMIFAC’s action plan (Plan de Convergence) (2003–2010) identifies its major themes as: harmonization of forest policy and taxation; inventory of flora and fauna; ecosystem management; conservation of biodiversity; sustainable use of natural resources; capacity-building and community participation; research; and innovative financing mechanisms (CARPE/COMIFAC 2010).

In late 2009, the Ministry of Water, Environment, Territory Management and Urbanism (Ministre de l’Eau, de l’Environnement, de l’Aménagement du Territoire et de l’Urbanisme) granted approval to Ecosystem Restoration Associates (ERA), a wholly owned subsidiary of Canadian ERA Carbon Offsets Ltd, to proceed with the design of a reforestation carbon offset project within and adjacent to the Kibira National Park. ERA is implementing the project through the Green Belt Action Group (Action Ceinture Vert pout l’Environement, ACVE) and the Rural Development Foundation (Fondation pour le Development de la Monde Rurale, FDMR) and has pledged to use local labor for the establishment and maintenance of nurseries, planting, tending seedlings, and forest protection. The GOB transferred the rights to the carbon offsets to ERA, which will sell them on the voluntary carbon market. ERA has pledged to use a portion of the proceeds to create income-generating programs for local communities (ERA 2010; ERA 2009).

The National Institute for Nature Conservation and the Environment (INECN) has engaged local communities in forest management programs in Kibira National Park since the 1970s. The program has had various components over the years, including plantation development and ecotourism activities. Over the decades of its operations, the development of watchdog committees has proved to be the most sustainable. The committees identify local forest uses and work with park officials to develop plans for local use of forest resources in exchange for assistance preventing destructive practices, such as illegal harvesting of wood, setting fires, and clearing land for cultivation. INECN has called for more support from donors to improve technical knowledge of sustainable forest management and conduct forest inventories (Nzojibwami 2003).

With the support of the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS), the governments of Burundi and Rwanda agreed to protect a large area of mountain forest in the Nyungwe-Kibira Landscape that provides habitat for chimpanzees and other vulnerable species (Mongabay 2008).

DONOR INTERVENTIONS AND INVESTMENTS

Burundi is a partner country within USAID’s Central African Regional Program for the Environment (CARPE) initiative aimed at promoting sustainable natural resource management in the Congo Basin. CARPE programs help governments implement sustainable forest and biodiversity management practices, strengthen environmental governance, and work to monitor forests and other natural resources throughout the region. CARPE is currently focusing on 12 priority landscapes that do not currently include Burundi’s forests (CARPE/COMIFAC 2010).

The National Committee of the Netherlands (IUCN) initiated the EUR €68,680 Valorization of Native Tree Species of Burundi project in 2009 to improve awareness, knowledge, and hands-on experience on the potential role of indigenous tree species in agroforestry in Burundi. The main activities planned are: research regarding local use of indigenous species for agroforestry; organization of a conference and roundtable on management of forestry resources in Burundi to discuss current agroforestry practices; generation of attention for indigenous alternatives; and the creation of 60 hectares of pilot sites for reforestation with indigenous tree species (60 hectares). The Burundian Agricultural Research Institute (ISABU) and provincial agriculture department will provide technical support and will monitor the planted trees after the project (IUCN 2009).

The US Forest Service, which conducted a natural resources assessment for the government in 2006, plans to partner with the government and USAID to assist in the development of improved watershed-level resource protection efforts – including nurseries, reforestation, and erosion control – and strengthen the policy framework protecting the country’s forests. USAID FY 2011 involvement in this area will consist in water rehabilitation under the MYAP program and clean water and sanitation under the GDA-WADA project.

The last large watershed protection program in Burundi was funded and managed by UNDP and the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) in the late 1990s and early 2000s. The Support for Environment Restoration and Management project (1997–2002) was active in five areas of the country and included components dedicated to reforestation of rocky ridges to reduce runoff and limit the impact of erosion. The project trained students at Burundi’s Agricultural Technical Training Institute in participatory forestry and agroforestry management, including experimental agroforestry management measures for farmers (Koyo 2004).

Minerals

RESOURCE QUANTITY, QUALITY, USE AND DISTRIBUTION

Although Burundi is not a globally significant producer or consumer of minerals, the country has commercial quantities of nickel (6% of known world reserves), phosphates, vanadium, peat, and alluvial gold, and niobium and tantalum are produced on an artisanal scale. The country also has deposits of iron, limestone, uranium, titanium, carbonatites, and cassiterite under varying exploration and production efforts. Burundi exported 2170 kilograms of gold in 2008, with between a quarter and a half produced by artisanal miners. Most mining takes place in Kirundo, Kayanza, Muyinga, and Citiboke provinces (Yager 2009; GOB 2006).

Only a small number of companies are active in Burundi’s mining sector, although the number of foreign companies engaged in exploration is increasing. The privately owned company Comptoir Minier des Exploitations du Burundi SA (COMEBU) is mining gold, niobium, tin, tungsten, and tantalum. The State- owned Office National de la Tourbe (ONATOUR) produces peat, and artisanal miners produce alluvial gold. The government awarded the British company Surestream Petroleum Ltd. exploration licenses on land near Lake Tanganyika. The company is proceeding with its environmental impact assessment in 2010, with a seismic study to follow in 2011. The government identifies the lack of sufficient, reliable energy as the biggest challenge to growth in the sector (Yager 2009; Backer and Binyingo 2008; Davenport 2008; Surestream 2010).

Mining activities have caused environmental damage in many areas. Artisanal mining for tantalum (coltan) takes place in hundreds of sites in northern Burundi. The operations remove natural soil cover, exposing bare rock that can leech toxic and radioactive elements. The course tailing fill natural waterways and flow over fertile land in valleys. Brick quarries are often established on hillsides, along flood plains, on channel banks, and in wetlands. The quarries cause sedimentation and erosion, with serious loss of soil and soil productivity (Athman et al. 2006; Biryabarema et al. 2009).

LEGAL FRAMEWORK

The Mining and Petroleum Act of 1976 (amended 1982) is the primary law governing allocation and use of mineral resources. Other laws include Decree Law No. 1/41 of 26 November 1992 on the Organization of Public Hydraulics; regulations to the 1976 Mining and Petroleum Act; and Revision to the Investment Code of Burundi, 6 September 1967. The Mining Code, which some legal practitioners describe as investor- friendly but outdated, is being revised (Backer and Binyingo 2008).

TENURE ISSUES

The Mining and Petroleum Act of 1976 provides for authorizations, permits, licenses, and concessions for mineral and petroleum resources:

- Authorizations to prospect are granted for a pre-defined perimeter for two years and are renewable. The authorization is non-exclusive, non-transferable, and revocable and does not grant any title in the minerals.

- Research permits are granted by governmental decree to applicants who can demonstrate sufficient technical and financial capacity to: establish the existence of deposits discovered at the prospecting stage; evaluate the reserves in terms of quantity and usefulness; and evaluate the conditions for the mining or production of the resources, their development, and the opportunities for industrial use and processing. Research permits require a public procurement procedure. Permits are exclusive and transferable subject to prior authorization. Prior to expiration of a research permit, the permit-holder has a right to an exploitation license provided that there is sufficient proof of the existence of a deposit within the perimeter for which the permit was granted.

- An exploitation license grants the right to industrial processing of minerals, their transformation, trading, and exportation. Exploitation licenses are available for 5-year terms, with two renewals.

- Concessions are granted for a period of 25 years, with the possibility of two 10-year renewals. A holder of an exploitation license can apply for a mining concession if he or she can demonstrate that the deposit is of sufficient importance (Backer and Binyingo 2008).

GOVERNMENT ADMINISTRATION AND INSTITUTIONS

The Ministry of Water, Energy and Mines is responsible for managing the allocation and exploitation of mineral resources (GOB 2006; Morgan 2009).

GOVERNMENT REFORMS, INTERVENTIONS AND INVESTMENTS

The GOB has identified the revitalization of the mining sector as a priority. The GOB began the process of reforming the legal and regulatory framework to attract local and foreign investors in 2008, and new legislation is expected in 2010 or 2011. In addition to the promotion of the industry with potential investors, the government also plans to promote small-scale mining and semi-industrial activities (GOB 2006; World Bank 2010; Morgan 2009).

As part of its plan to develop its transport sector to increase trade and investment, Burundi is participating in the African Union/New Partnership for Africa’s Development (AU/NEPAD) feasibility study for a possible US $4 billion extension of a railway line for Tanzania (Isaka)-Rwanda-Burundi. The project is part of the Dar es Salaam‐Kigali‐Bujumbura Central Transport Corridor, which would provide an alternative route to the seaport of Dar es Salaam for landlocked countries Burundi and Rwanda, promoting inter‐state trade and investment in main areas of economic activity, including mining. The study was approved in November 2009, with completion scheduled for December 2011. The African Development Fund (ADF) provided most of the financing for the study; with the governments of Burundi, Tanzania, and Rwanda each contributing about 1.6% of the cost (AU/NEPAD 2009; ADF 2009).

DONOR INTERVENTIONS AND INVESTMENTS

The World Bank has a 3-year (2008–2010) Reform and Modernization of Burundi’s Mining Code and Agreements project to assist the GOB in updating the legal framework governing the mining sector and provide assistance with the development of model contracts. The work was contracted to Dewey & LeBoeuf LLP. Progress on the project has not been reported (World Bank 2010).