Overview

“Corruption and economic mismanagement, lack of opportunities for youth, and the underdevelopment of rural areas” were identified in the postwar truth commission process as underlying causes of the conflicts that devastated Sierra Leone between 1991 and 2002 (Freeman 2008, 1). Donor support to Sierra Leone since 2002 has enabled combatants to be disarmed and reintegrated into society, many of those internally displaced by the war to return home, and the elements of a democratic state to be put in place. But economic performance remains inadequate to move Sierra Leone up from its place at or near the bottom rank of the Human Development Index. Many young men have turned away from agriculture toward mining, where they appear to find higher incomes but exploitative working conditions. Further, national and local governance are still believed by many to be prone to the same kinds of corruption and mismanagement that characterized Sierra Leone before the conflict. New approaches seem to be needed to establish property rights in ways that would encourage investment and rising productivity (especially in agriculture) and give landholders and local communities a stake in Sierra Leone’s economic future; and to provide transparent and accountable governance of the country’s considerable natural resources.

Exactly what these new approaches might be, however, is still a matter for analysis and political debate. Given the country’s increased reliance on imported rice for survival over the period of conflict, for example, many have recommended rapid revitalization of the agricultural sector through expansion of irrigation in the country’s inland valleys and wetlands, and greater investment in infrastructure to connect rural areas, where just over 60% of the country’s 5.5 million people live. The Government’s 2009 National Rice Strategy proposes that efforts to achieve national self-sufficiency in rice production are “the only solution” to food security and economic growth. Others question the institutional capacity of the government and local communities to support this agricultural strategy, including the ability to train farmers in the new methods of cultivation required for irrigated production, and the willingness of local paramount chiefs to appropriately handle the “micro-politics” that surround the allocation of land subject to customary tenure, especially when land was abandoned during the years of conflict. Close monitoring of Sierra Leone’s initial development efforts will be essential to identifying those factors that impede or accelerate achievement of higher productivity, incomes, and rural well-being in agriculture.

Similar analyses and debates will underpin development strategies for the mineral and forestry sectors, sectors of the economy which provide Sierra Leone with considerable potential for wealth. The 2009 Poverty Reduction Strategy Paper underscores the importance of legal reforms of the mining and forestry sectors for jobs and revenues. Some legal reform has been achieved in the mining sector. Based on past experience, however, implementation of the new legal framework will require strong resource governance structures able to meet the challenge of assuring that the benefits from the legal exploitation of the country’s mineral and forest resources are widely distributed and/or invested for the good of all citizens. This is not an easy challenge.

Key Issues and Intervention Constraints

Developing alternatives to slash-and-burn technologies should be an effective way to address the labor constraints now being experienced by Sierra Leone’s farmers as they redevelop their farms post-conflict. Moving toward more sustainable systems of cultivation will require, inter alia: (1) defining new rules for allocation of land both to provide greater incentives to young farmers, including women, and investors (formulation of new rules must include participation by elected local officials and the paramount chiefs – whose power to allocate land has been restored and, in some ways, strengthened by government’s efforts to decentralize authority); (2) investments in research to define locally adapted packages of improved technologies; and (3) efforts to link rural areas to urban markets through infrastructure. Donor assistance will be essential to funding these broad initiatives as well as providing technical analysis and advisory services as needed.

This inventory should be accompanied by a review of the legislative and regulatory frameworks providing for use of this land and the safeguarding of biodiversity. It will also be important to support the establishment of civil society monitoring as well as institutions that would add transparency and accountability in government operations regarding these resources. Donor funding will be essential to completing these actions, but local and regional environmental expertise should be engaged to lead the effort.

Donors should work with the government to ensure that all citizens derive greater benefits from the country’s mineral wealth by: enhancing the rights of communities and artisanal miners to land and to a fair share of the proceeds from minerals; addressing corruption; and managing environmental impacts more effectively (reducing pollution and increasing reclamation efforts). Donors can continue to support the Kimberley Process but might also consider other third-party monitoring involvement in other aspects of minerals development.

Address the gender discrimination that seems to be inherent in traditional governance structures at the local level and contributing both to economic injustice and to a generation gap – with youth no longer willing to accept customary rules and the imposition of customary authority regarding marriage, labor allocation, and economic opportunities. Methodologies for addressing these issues through community dialogues have been developed and applied elsewhere. Donors, working with NGO partners, should consider the possibility of their utility in Sierra Leone.

Summary

Sierra Leone’s civil war (1991 to 2002) wreaked havoc on the country’s social fabric and its economy, exposing its people to extreme hardship and vulnerability. The war destroyed infrastructure and caused institutions to disintegrate and people to flee. The end of the war has been followed by seven years of recovery and improvement in Sierra Leone’s economic performance and prospects. However, the causes of the conflict – which according to most observers were rooted in governmental corruption and mismanagement of Sierra Leone’s considerable natural resources – persist in many areas. Much remains to be done to put the country on a path to sustainable peace and social and economic development.

Sierra Leone is a highly diverse country, with a population of about 5.5 million speaking more than a dozen languages. The country includes coastal zones, wooded hill country, an upland plateau, and, in the east, mountains of nearly 2000 meters. The country is rich in  resources, with reserves of diamonds, rutile (titanium dioxide) and bauxite, productive agricultural lands, and rainforests. Offshore oil reserves have recently been discovered. The “resource curse” – rather than tensions between ethnic or tribal groups – has been visited upon Sierra Leone as urban, military, and rural elites have attempted to use their positions to control resources for personal gain and power rather than for the benefit of the citizens. Poverty, malnutrition, and inadequate levels of health care and schooling have been the result of this inequitable distribution of resources and have contributed to the country’s position near the bottom of the Human Development Index.

resources, with reserves of diamonds, rutile (titanium dioxide) and bauxite, productive agricultural lands, and rainforests. Offshore oil reserves have recently been discovered. The “resource curse” – rather than tensions between ethnic or tribal groups – has been visited upon Sierra Leone as urban, military, and rural elites have attempted to use their positions to control resources for personal gain and power rather than for the benefit of the citizens. Poverty, malnutrition, and inadequate levels of health care and schooling have been the result of this inequitable distribution of resources and have contributed to the country’s position near the bottom of the Human Development Index.

Rural land is generally abundant, and availability of land is not considered a constraint in agricultural production. However, locally powerful families and chiefs often control access to the highly valued wetlands and inland valley swamps that permit intensive, year-round production, and less powerful members of rural communities, including women, may not have equal opportunities to access productive land. In the capital of Freetown and its environs (called the “Western Area”), much of the land is privately held in freehold tenure. Urban populations grew significantly in the years of conflict (to about 40% of the total population), increasing the numbers of people living in slums, and encroaching on the state and private land surrounding the city.

Customary law governs land tenure throughout the rest of the country, and traditional paramount chiefs control land access. Conflict displaced rural populations in many areas (with more than a quarter of the population displaced at one time or another) and many local authorities were overruled by various factions in the conflict or simply killed. In the post-conflict period, donors supported government efforts to restore the authority of paramount chiefs in order to reestablish stability in the rural areas and hasten resumption of agricultural development and decentralization. Some observers have noted that the restoration of the chieftaincy system potentially perpetuates abuses of power and exploitation of the local population, especially the rural youth. Ex-combatants and rural youth are less likely to return to rural areas and provide much-needed agricultural labor if they believe the chiefs will control and ultimately limit their economic opportunities and status in rural communities.

Sierra Leone enjoys vast surface water and groundwater resources, but most citizens do not have access to potable water. The lack of long-term maintenance of public infrastructure during the civil war, weak institutional capacity, the absence of a comprehensive legal framework, and inadequate funding have resulted in significant constraints to the supply of water to the population.

Sierra Leone has substantial mineral resources, including diamonds, bauxite, and gold. The government has recently reformed the legal framework governing the mining sector in order to attract investment and provide revenue for rural and urban development and environmental protection.

Land

LAND USE

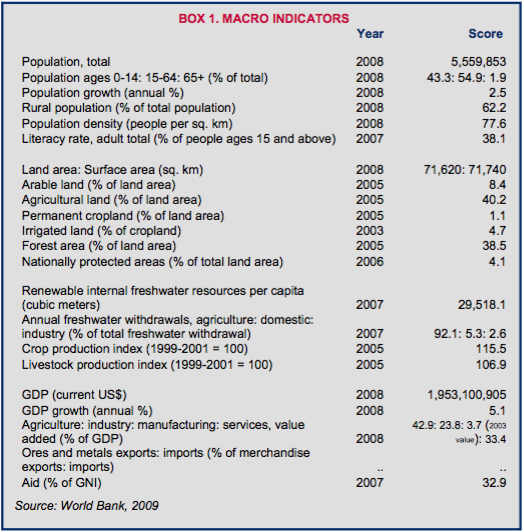

Sierra Leone’s 5.5 million people (2008) occupy 71,600 square kilometers of land, of which 40% is agricultural, 39% is forested, and 4% is protected. The population is 62% rural and 38% urban. The country’s 2008 US $1.9 billion GDP is derived from the agricultural (43%), service (33%), and industrial (24%) sectors. Within the industrial sector, mining contributes about 20% of the industrial sector’s contribution to the GDP. Both mining and agricultural activities provide employment for rural populations (World Bank 2009a; Hooge 2008).

Sierra Leone’s decade-long civil war deepened and expanded the country’s existing poverty, resulting in social dislocation, war victims, and the loss of coping mechanisms. Roughly 80% of Sierra Leone’s population is living in absolute poverty. The country ranked 180th (of 182) countries on the 2009 Human Development Index (2007 data) (World Bank 2005b; UNDP 2009).

The 1991–2002 conflict severely disrupted the agricultural sector, causing both lower production and greater poverty. People fled their farms in the face of invasions from the Revolutionary United Front (RUF) or counter-attacks by the military or by UN peacekeeping forces. As much as one-third of the population was displaced by the war, and significant post-conflict efforts have focused on enabling people to return to their agricultural lands. Imports of rice, the staple food of Sierra Leone, increased dramatically throughout the war years, but in the last few years, local production has begun to restore the country to self-sufficiency in this crop. Most rice is grown in rainfed upland areas (GOSL 2009a).

About 1% of Sierra Leone’s land is under cultivation, and roughly 5% of cropland is irrigated. No recent data on its extent is available, but about 155,000 hectares are believed to be subject to some form of water management, with fewer than 30,000 hectares believed to be irrigated. Irrigable potential, however, is estimated to be more than 800,000 hectares. With the benefit of national peace, the agricultural sector contributed to a 7.4% increase in GDP since 2004 through an expansion in land under cultivation (FAO 2005b; World Bank and AfDB 2010).

The predominant type of farming is the bush fallow system, a labor-intensive method of production that generally limits cultivated holdings to between 0.5 and 2 hectares. Up to 10 different crops are grown in mixed stands in one season; rainfed rice dominates, followed by cassava, sweet potatoes, and legumes. Low yields and productivity are the result of the use of inadequate and rudimentary farm inputs. The land is degraded due to the practice of shifting cultivation, recurrent bushfires, overgrazing, and shortening of fallow periods (Chemonics et al. 2007; FAO 2005b).

LAND DISTRIBUTION

Sierra Leone is divided into three provinces (Southern, Eastern, and Northern) and the Western Area. The country has about 13 tribes, eight of which are major ethnic groups that have historically resided in distinct areas of the country. The Susu, Limba, and Koranko were generally associated with the northern regions, the Temne in the central and western region, the Kono in the central eastern region, and the Mende in the south. The Creole and Sherbro primarily inhabited coastal regions. The years of conflict, urban migration, and mining industry have created a more mixed distribution of people in the last decades. Sierra Leone does not suffer from severe ethnic/tribal tensions, but there is a deep rift between the few rich elite and the bulk of people who continue to live in desperate poverty (MRGI 2005; Kabbah 2006).

Land in rural areas is generally abundant; availability of land is not considered a constraint in agricultural production, although access to wetlands (a more highly valued resource) is more limited. In most of the country, land access is controlled by paramount chiefs. These  traditional authorities (newly re-empowered by the current democratic, decentralized government) allocate land-use rights to extended families for their further division among family members. In principle, the paramount chiefs hold the land in trust for those extended families or lineages attached to a particular chiefdom. No significant land-related decision is final until the paramount chief approves (Unruh and Turay 2006).

traditional authorities (newly re-empowered by the current democratic, decentralized government) allocate land-use rights to extended families for their further division among family members. In principle, the paramount chiefs hold the land in trust for those extended families or lineages attached to a particular chiefdom. No significant land-related decision is final until the paramount chief approves (Unruh and Turay 2006).

Chiefs can grant or obstruct any individual’s access to land, especially if they are migrants from outside the chiefdom (known as “strangers”) or have abandoned their land. The chief presides over land disputes and determines which claims are valid. This power is more critical to livelihoods and economic opportunities where the land is rich in natural resources. Paramount chiefs and other levels of traditional authority exert control over behavior and social customs, including levying fines for transgressions and determining if and when a person may marry. Young men in particular could face heavy fines and high bride prices that required them to commit to years of agricultural labor for local landowners, often under exploitative conditions. Some experts cite this level of control over economic independence and marriage as one of the reasons young men and women were so easily recruited as soldiers for the civil war (Dale 2008; Maconachie 2008).

Since the end of the war, the paramount chief’s control over land matters has continued (or been reestablished) and in some areas increased. The 2009 Chieftaincy Act recognizes the role of paramount chiefs in safeguarding customs and supporting local development. In some rural areas the paramount chiefs and chieftaincy system proved to be a significant post-conflict stabilizing force. However, the dominance of the institution also creates potential for perpetuation of exploitative relationships, patronage, and corruption (Maconachie 2008; Unruh and Turay 2006; GOSL 2009b).

LEGAL FRAMEWORK

Sierra Leone’s Constitution provides that sovereignty belongs to the people of Sierra Leone and grants the right to the enjoyment of property but does not specifically address the vesting or ownership of the country’s land (GOSL 1991; Williams 2006).

The formal laws addressing land rights and governance in Sierra Leone predate the civil war and include the 1966 Non-Citizens (Interest in Land) Act; the 1927 Protectorate Land Act Ordinance Act; the 1960 Provinces Land Act, as amended; the 1960 Crown Lands Act, as amended; the Imperial Statutes (Law of Property) Adoption Ordinance; the 2001 Town and Country Planning Act, and the 2006 Summary Ejectment Act (Reynolds and Flores 2009; Williams 2006).

The statutory laws recognize private freehold land in Freetown and the Western Area (previously a British colony), while under the Provinces Land Act land in the three provinces (previously a British protectorate) is governed by customary law with chiefs serving as custodians. Customary law is unwritten, varies across chiefdoms, and evolves over time. Customary law is enforceable in formal and informal courts (Unruh 2008; Williams 2006; Maconachie 2008).

The 2004 Local Government Act gives local councils the right to acquire and hold land. Local councils have the responsibility for the creation and improvement of human settlements and are responsible for creating development plans (Williams 2006).

Sierra Leone’s 2005 National Land Policy promotes the objectives of equal opportunity and sustainable social and economic development. The principles guiding the Land Policy include: (1) protecting the common national or communal property held in trust for the people; (2) preserving existing rights of private ownership; and (3) recognizing the private sector as the engine of growth and development, subject to national land-use guidelines and rights of landowners and their descendants (Williams 2006).

The 2009 Chieftaincy Act provides that paramount chiefs are responsible for collecting taxes, ensuring good governance and order within their jurisdictions, preserving and promoting customs and traditions of the region, as appropriate, and serving as agents of development of the region (Williams 2006; GOSL 2009b).

Two legislative efforts to reform the legal framework for land are pending. A proposed Land Commissions Act establishing a Land Commission with a range of responsibilities and ambit of authority (including land allocation, policy implantation, and execution of a registration program) has been drafted and presented for adoption by Parliament. Also, a proposed law promoting the commercial use of land has been drafted. The draft law attempts to improve land tenure security by allowing for longer lease terms, and providing for a lease contract that can be mortgaged, and payment to tenants for fixtures and improvements (such as trees). There is no indication that either draft law has been enacted (Unruh and Turay 2006).

TENURE TYPES

Land in Sierra Leone is classified as state land, private land, or communal land. In the Western Area, some land is held in private ownership, with freehold rights of exclusivity, use, and transfer. The informal settlements have been constructed on urban and peri-urban land in and around Freetown and are subject to both statutory and customary tenure systems (GOSL 2009a; Unruh and Turay 2006).

Most of the country’s land is chieftaincy land that is under customary tenure with chiefs serving as custodians of the land. The land is considered held by ancestors, living community members, and unborn family members; the current generation is responsible for managing and preserving the land in the interests of the ancestors and future generations. Much of the land has been individualized in the names of lineages, families, and individuals (Unruh and Turay 2006; Dale 2008).

Most chieftaincy land is held by extended families. Families have rights of access, use, and transfer by lease. In some areas people from outside the chiefdom, including migrants, tenants, ex-combatants, and foreigners (collectively known as “strangers”), make up 20–40% of the chiefdom populations. Landowning families lease land to “strangers” on an annual basis. The “strangers” pay a nominal amount of the crop-yield to the family and are restricted from planting trees and perennial crops as an acknowledgement that they have no long-term interest in the land (Unruh 2008; Unruh and Turay 2006).

Rights to sell chieftaincy land are generally limited to sales within the family or community and are not recorded; in most regions, customary law prohibits the sale of chieftaincy land to non-family or non-community members. Some chieftaincy land is retained as communal land for community use (Williams 2006; Unruh and Turay 2006; Maconachie 2008; Dale 2008).

SECURING LAND RIGHTS

Land in Sierra Leone can be obtained by purchase, lease, allocation, inheritance, gift, clearing, and adverse possession and squatting. Private freehold land and some state-owned land can be transferred by sale or lease. Chieftaincy land under customary tenure can be obtained by purchase (citizens only) or lease. Private and chieftaincy land that has been individualized into family holdings can be transferred by inheritance. Land transfers of family holdings of chieftaincy land are subject to approval of all family members and the paramount chief. Chiefs may lease communal land that has not been individualized as family or individual holdings (FIAS 2005; Unruh and Turay 2006).

The majority of people in Sierra Leone access land through membership in a family or community, clearing new land, inheritance, and leaseholds. The years of conflict and rural poverty have caused many rural residents to move to peri-urban and urban areas where they squat on state or private land. Migrants have erected shacks on the hills above Freetown, along beaches, and at the edges of forests (GOSL 2009a; Williams 2006; Dale 2008).

With the support of NGOs, youth groups and women’s cultivation groups in some areas have been assisted by paramount chiefs to obtain access to land for farming. The paramount chiefs either lease the groups available land in the chiefdom or arrange for the groups to lease land from a landholding family. In most cases, at least one member of the leasing group is from the community (Unruh and Turay 2006).

The 1960 Registration of Instruments Act provides for registration of conveyances of land interests. The registration is conducted by the Office of Administrator and Register General (OARG). The parties file a copy of the conveyance document and land survey. Registration does not provide the parties with security of tenure. The OARG does not maintain a cadastre, and boundaries, land location, and land rights are not recorded. The OARG does not verify the survey, land tenure, or existence of other registrations impacting the land; nothing prevents multiple, inconsistent filing relating to the same property (FIAS 2005).

By statute, foreign persons and foreign legal entities cannot purchase land; but they may acquire leaseholds for periods up to 99 years. An additional restriction on land ownership prohibits the purchase of land by “non-natives,” an undefined term typically referring to anyone who is not a member of a provincial tribe. In addition to those residents of Freetown, this restriction can prohibit women and multi-ethnic children from purchasing land, since national and tribal citizenship is passed down through the male line (Dale 2008; Williams 2006).

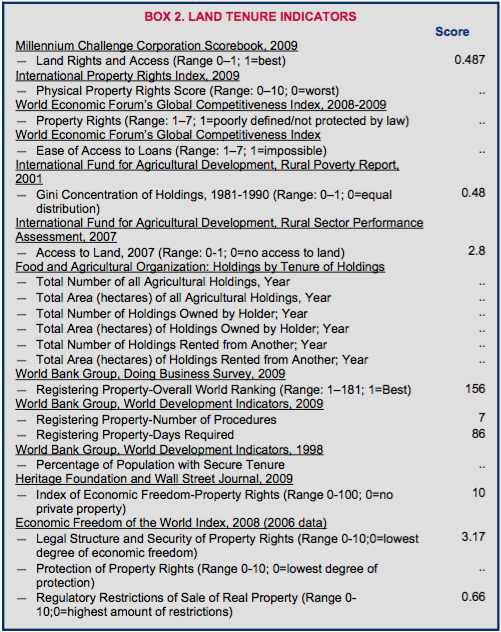

High land tenure insecurity in Sierra Leone is fueled by: lack of a comprehensive and integrated legal framework governing land; application of uncodified customary law to land transfers; absence of a reliable record of landholdings; prevalence of fraudulent land documents; the practice of ignoring or changing the terms of land leases; the number of family members with an interest in a single landholding; a history of ad hoc decision-making by land authorities; and the practice of shifting cultivation (which requires retaining the ability to quickly retake uncultivated land). Indications of insecurity include landholder prohibitions against lessees planting trees or installing irrigation facilities, one-year leases, and absence of landlord-tenant relationships based on rents or other economic arrangements (Richards 2005; Unruh and Turay 2006).

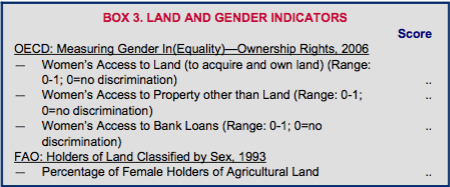

INTRA-HOUSEHOLD RIGHTS TO LAND AND GENDER DIFFERENCES

The Constitution of Sierra Leone prohibits discrimination on the basis of gender, and provides for equal rights for women to all opportunities and benefits based on merit. However, the Constitution exempts personal laws (e.g., laws regarding marriage, divorce, devolution of property) from the mandate of nondiscrimination. The 2007 Devolution of Estate Act provides for a woman’s right to inherit her deceased husband’s property if he dies intestate (i.e., without a will) and grants a rebuttable presumption that a deceased’s will intended to provide for a surviving spouse and any children of the deceased. The Act recognizes marriages entered into under customary law and the rights of polygamous spouses, and imposes criminal penalties for evicting a surviving spouse or child from the marital home before formal distribution of the estate. The Act does not extend to family property (i.e., property held jointly by several family members), chieftaincy property, or community property (i.e., property held collectively by a community) and is therefore inapplicable to most rural land (GOSL 1991; GOSL 2007a).

The Constitution of Sierra Leone prohibits discrimination on the basis of gender, and provides for equal rights for women to all opportunities and benefits based on merit. However, the Constitution exempts personal laws (e.g., laws regarding marriage, divorce, devolution of property) from the mandate of nondiscrimination. The 2007 Devolution of Estate Act provides for a woman’s right to inherit her deceased husband’s property if he dies intestate (i.e., without a will) and grants a rebuttable presumption that a deceased’s will intended to provide for a surviving spouse and any children of the deceased. The Act recognizes marriages entered into under customary law and the rights of polygamous spouses, and imposes criminal penalties for evicting a surviving spouse or child from the marital home before formal distribution of the estate. The Act does not extend to family property (i.e., property held jointly by several family members), chieftaincy property, or community property (i.e., property held collectively by a community) and is therefore inapplicable to most rural land (GOSL 1991; GOSL 2007a).

Despite provisions in the formal law supporting women’s rights, few women own land in Sierra Leone. The primary route to land ownership – inheritance – is denied to most women in northern Sierra Leone, with an exception for those who are members of the Limba tribe, which recognizes women’s rights to inherit land to some degree. Women in the northern areas may be denied the right to rent a plot in urban areas and be forced from their marital home at the death of their husbands. Custom may prevent them from activities that create rights to land, such as tree planting. In the southern and eastern regions of the country, including among the Temne tribe, women’s rights tend to be stronger: some women report inheriting land and forming cooperatives to gain and retain access to land for cultivation (Unruh and Turay 2006; Williams 2006).

In many rural areas of the country, marriage customs continue to reflect conditions of production and reproduction associated with the days of domestic slavery. Most young women are married in their teenage years, often to older polygamists. Young men who marry are saddled with a large debt, and their labor is devoted to working the land of local elites and in-laws as a form of repayment for their brides. Those who enter into informal unions risk being fined for “woman damage,” and they have the choice of spending years working off the debt or fleeing (Richards n.d.; Maconachie 2008).

LAND ADMINISTRATION AND INSTITUTIONS

The Ministry of Lands, Country Planning and Environment is responsible for: managing state lands; compulsory acquisition of land; surveying and mapping; planning; development; and establishment and enforcement of building codes. The Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Food Security (MAFFS) has the mandate to achieve sustainable food security and reduce poverty through agricultural intensification, diversification, and the efficient management of the natural resource base. The MAFFS is responsible for supporting the production of all crops and livestock in an environmentally sustainable manner and ensuring food security (Williams 2006; AfDevInfo 2010).

The Ministry of Local Government and Community Development (formerly Ministry of Internal Affairs, Local Government and Rural Affairs) ensures the implementation of the government’s local government reform and decentralization program, and assists in the identification, planning, implementation and monitoring of development programs that support poverty reduction and the socioeconomic revitalization (Williams 2006; AfDevInfo 2010).

Paramount chiefs in Sierra Leone’s 149 chiefdoms are considered the traditional custodians of the land in their chiefdoms. The paramount chiefs are assisted by sub-chiefs at the lower administrative levels. In post-war years, the government’s efforts to decentralize various functions to local and district council have (to varying degrees) recognized the need to work with the chieftaincy in land matters (Dale 2008; Unruh and Turay 2006; Maconachie 2008).

LAND MARKETS AND INVESTMENTS

Since the early 1900s, land markets have been active in the coastal regions and gradually emerged in other parts of the Western Area as pressure on land increased. The formal land market is restricted to the Western Area. Registration of the sale of land requires seven steps, an average of 236 days, and costs 12.4% of the property value. The steps include verifying at the Property Registry that the seller has title, obtaining a survey, filing the survey at the Ministry of Land and Housing, preparing a purchase and sale agreement, obtaining a tax clearance certificate from the National Revenue Authority, and paying the fees and taxes (World Bank 2008; Knox 1998).

In November 2008, the Ministry of Lands announced a moratorium on all land transactions in the Western Area due to problems apportioning land, the prevalence of false title deeds, and multiple claims to the same land. There is no published report of the current status of the moratorium (GOSL 2008a).

In the remainder of the country, customary law dictates against permanent transfers of rural land. Land sales do occur but are generally conducted within families, lineages, and communities. Where land sales do occur, purchasers have little tenure security. Sellers may seek additional payment from the buyer when, over time (even after a generation), the value of the land has increased. Other instances have arisen in which a member of the seller’s extended family tries to invalidate the sale. Foreigners are not permitted to buy land in Sierra Leone (Unruh 2008; Unruh and Turay 2006).

Sierra Leone has an active lease market in state and private land and land held under customary tenure. Lease terms are negotiated between the parties, and must include the approval of the paramount chief for chiefdom land, even when held by individuals or families. Tenure security is commonly quite low. Cases exist where investors have applied for a lease from the government, but the government fails to consult the chief before granting the lease, thereby resulting in competing claims. Negotiated lease terms are rarely enforced, and parties routinely ignore agreed terms, including the length of the lease term and restrictions on land uses and development (FIAS 2005; Unruh and Turay 2006).

COMPULSORY ACQUISITION OF PRIVATE PROPERTY RIGHTS BY GOVERNMENT

The 1991 Constitution of Sierra Leone provides that no property shall be taken except where “necessary in the interests of defense, public safety, public order, public morality, public health, town and country planning,” and for “promotion of public benefit or public welfare.” Under such circumstances, there must be “prompt payment of adequate compensation.” Constitutional protections do not apply for takings based on other legal authority, including for purposes of “carrying out . . . agricultural development or improvement which the owner or occupier of the land has been required, and without reasonable or lawful excuse refused or failed to carry out” (GOSL 1991, Art. 21).

LAND DISPUTES AND CONFLICTS

Land disputes are common in Sierra Leone. Disputes arise as a result of: lack of consent (especially of all family members) to a land transfer; use of fraudulent documents; multiple interests asserted with regard to the same property; erroneous surveys; exercise of authority over land by the paramount chief; and intrafamily disputes over rights to land; including offspring of polygamous marriages. In the Western Area, land disputes account for 70% of the higher court dockets. A 2001–2006 study identified 17% of the disputes pending as between landowning groups or disputes over boundaries of family land (Williams 2006; Dale 2008; Chauveau and Richards 2008; Unruh and Turay 2006; GOSL 2005).

Some researchers suggest that a source of the conflict leading to the civil war was tensions among rural landowning elite seeking labor for their fields, and impoverished rural youth. In some areas, paramount chiefs helped supply labor to landowners by controlling access to land and assessing fines and fees on local youth, who were required to work off fines by performing agricultural labor, often under exploitative conditions. According to some researchers, the nature of the agrarian relations constrained the economic future of rural youth, leading to discontent and disputes and creating fertile ground for the insurgency’s recruitment efforts (Richards 2005; Maconachie 2008).

In the 149 chiefdoms, the chieftaincy hears land disputes. The traditional power exercised by the chieftaincy maintained much of its legitimacy through the years of conflict, and the government’s decentralization plan and the 2009 Chieftaincy Act reinforced the chieftaincy’s power in many areas. An aggrieved person usually goes to the lowest level of the chieftaincy structure, the village chief, for assistance. Appeals and more serious disputes are taken to a sub-chief, followed by the paramount chief. Those with a dispute may also seek assistance from a religious leader or a “secret society” to which most rural residents belong (Manning 2009; Unruh and Turay 2006).

The court of first instance outside the chieftaincy is the local court or native administration court. Each chieftaincy has one or two courts that apply customary law, which varies from chiefdom to chiefdom. Local courts are under the authority of the Ministry of Local Government and, thus, outside the traditional judicial system. By statute, local courts mete out justice based on principles of equity, good conscience, and natural justice. The courts have been heavily criticized for the low standard of justice they provide, and access is limited to those with financial means. Customary Law Officers control referral of cases to higher courts. Observers report court corruption and bias based on close relations between ruling families and the Local Court Chairman, and exertion of control by the chiefs. Women face barriers to the courts due to lack of knowledge of their legal rights, low literacy levels, and cultural constraints (Dale 2008; Williams 2006; Manning 2009).

KEY LAND ISSUES AND GOVERNMENT INTERVENTIONS

The 2005 Land Policy acknowledges numerous problems plaguing land tenure and administration in Sierra Leone, including: general lack of discipline in the land market; unclear boundaries; illegal acquisition of state land; inadequate security of tenure; difficulty accessing land for development purposes; weak land administration and management; and low levels of consultation, coordination and cooperation. Sierra Leone has been active in the Africa Union Comprehensive Africa Agriculture Development Plan (CAADP) approach, and its National Sustainable Agriculture Development Plan is aligned with the CAADP. The government has committed to fulfill the Maputo Pledge of allocating at least 10% of the budget to the agricultural sector and to seek to achieve an annual growth rate of 6% in that sector (World Bank and AfDB 2010; Williams 2006; GOSL 2009a).

The Sierra Leone Poverty Reduction Strategy Paper II (PRSP II) (2008–2012) popularly called the Agenda for Change and the joint assessment of the strategy by the World Bank and International Finance Corporation (IFC) recognize the following needs with relation to the agricultural sector: (1) to encourage greater private-sector participation in the agricultural sector, including in the supply of agricultural inputs and equipment as well as extension services; (2) to develop a plan for how the land tenure system can provide better incentives for investments in agriculture; (3) to support interventions for tree crops and diversification of food sources outside of rice; (4) to assess the economic and social cost-benefit of farm mechanization given the existing high unemployment in some parts of the country; and (5) to enhance the role of rural credit and micro-credit programs in improving agriculture productivity. The strategy also identifies the need to develop and implement a Land Management Information System and to develop and implement land-use plans at national, regional and local levels (GOSL 2009a; World Bank 2009d).

DONOR INTERVENTIONS

USAID is implementing a multi-sectoral activity entitled Promoting Agriculture, Governance, and Environment (PAGE). The activity will increase agricultural productivity and farmer incomes through the use of a market-based approach to agriculture, and support of existing Farmer Field Schools. The Farmer Field Schools assist farmers to adopt improved agricultural methods, identify new opportunities (e.g., tree crops, value-added processing), and obtain access to credit. In order to establish the enabling policies necessary to implement PAGE activity interventions, USAID developed a new activity entitled Creating an Enabling Environment in Sierra Leone (CEPESL). CEPESL will provides the necessary framework (e.g., policies, laws, procedures) for PAGE interventions (e.g., agricultural production, co-forest management, extractive mining). In FY08, USAID built capacity of 662 agricultural and related organizations, and beneficiaries more than doubled their agricultural production. The budget for agricultural programs in FY10 is US $11.2 million (USAID 2009; USDOS 2009).

Between 2003 and 2007, USAID supported the US $8 million Promoting Linkages for Livelihoods Security and Economic Security (LINKS) project, which focused on improving farmers’ capacity to carry out market-oriented agriculture and manage businesses. The project: increased socially marginalized youth’s access to livelihood opportunities, including agriculture; improved access to agricultural inputs; established two microfinance institutions; and institutionalized marketing information (Weidemann Associates 2007).

The World Bank is funding a 6-year US $32 million Rural and Private Sector Development Project designed to improve efficiencies along the value chain of agricultural commodities. The project includes components to strengthen domestic distribution channels, support the production of agricultural exports such as cocoa and coffee, improve famers’ access to technology, and develop enabling policies and regulations. After the first two years, the project was restructured to support development of needed infrastructure (e.g., feeder roads) and to emphasize working with and empowering local councils. According to the Status of Projects in Execution FY09 report, the project was not progressing as planned due to unresolved problems with management arrangements (World Bank 2009c; World Bank 2009f; World Bank 2009g).

Several NGOs are working to publicize and educate the population and local authorities in Western Areas about the 1991 Constitution and the 2007 Devolution of Estate Act. The Lawyer’s Center for Legal Action (LAWCLA) has summarized the Devolution of Estate Act into comprehensible language. The Coalition of Women’s Movement is conducting a campaign in one district to sensitize the population about inheritance rights, including educating women and traditional authorities. The Movement for the Restoration of Democracy (MRD) is using radio programs to educate people about inheritance rights (Massaquoi 2009).

CARE has several projects in Sierra Leone that include providing capacity-building for the development of farmers’ associations, exposing farmers to conservation farming practices, and integrating women and other marginalized groups into agricultural development. CARE notes that the projects will establish land-use agreements in order to improve long-term access to land for women and other marginalized groups, and prevent and mitigate land conflicts related to gender and ethnicity. Project results have not been published to date (CARE n.d.).

Freshwater (Lakes, Rivers, Groundwater)

RESOURCE QUANTITY, QUALITY, USE AND DISTRIBUTION

Sierra Leone is located in the northern region of the equatorial rainforest zone and has a hot, humid climate. Rainfall ranges from 1900 millimeters to 4000 millimeters per year, and the country has vast surface and groundwater resources. Five major rivers – the Rokel, Jong, Sewa, Little Scarcies, and Moa – cross the country east to west, emptying into the Atlantic Ocean. The Great Scarcies River forms the country’s northern border with Guinea, and the Moro River forms the southern border with Liberia. Sierra Leone has 12 river basins, seven of which are shared with neighboring Guinea and Liberia. The country has 160 cubic kilometers of annual internal renewable water resources (FAO 2005b).

Agriculture withdraws the greatest percentage of water (93%), with the domestic and industrial sectors withdrawing 5% and 2%, respectively. Eighty percent of the rural population obtains its water from surface sources, including streams and ponds. Groundwater is used for a limited number of purposes, such as a small number of rural wells and to supply large cities (FAO 2005b).

The country’s water resources are unevenly distributed seasonally and geographically. Between December and April, only 11–17% of surface water resources are discharged, and there is insufficient water supply for domestic use and agriculture in most areas. As of 2003, only 22% of the population had access to safe drinking water, with the greatest access in the Western Area (46%) and lowest access in rural areas (14% in Kailahun, 200 miles east of Freetown). Constraints to greater drinking water coverage include lack of adequate storage facilities, the need to reconstruct infrastructure damaged or neglected during the civil war, and lack of clarity over institutional responsibility for management of water resources (FAO 2005b; Tearfund 2005; UNECA 2007; World Bank 2005a; World Bank 2005b).

Irrigated agriculture is severely underdeveloped and no recent data exists on its extent. There is potential for small-scale hydropower projects that could supply irrigated agriculture (FAO 2005b).

After almost 30 years in planning and construction, Sierra Leone’s major hydroelectric dam, the Bumbuna Dam, became operational in November 2009. The dam holds 428 cubic meters of water and currently supplies 50 megawatts of electricity to Freetown. A second project phase plans to add more capacity, build and rehabilitate old lines, and provide electricity to additional areas (VOA News 2010).

The country’s water resources are threatened by rapid population growth, soil erosion, increased industrial activities (especially mining), drainage of wetlands, and pollution of rivers (UNECA 2007).

LEGAL FRAMEWORK

Sierra Leone lacks a comprehensive legal framework governing it water resources. The sector is partially regulated by a handful of laws and regulations:

- The 1963 Water Supply and Control Act is national legislation addressing water rights, catchment management, and pollution. The legislation is outdated and does not appear to be referenced in the governance of water resources.

- The 1961 Guma Valley Act governs water rights and management in Guma Valley (Freetown and surrounding area).

- The 1990 Forestry Regulations include provisions on catchment management.

- The 2001 Sierra Leone Water Company Act obligates the Sierra Leone Water Company (SALWACO ) to develop and operate satisfactory water services at reasonable cost and on a self-supporting basis and develop and maintain waterworks necessary to ensure water services.

- The 2004 Local Government Act provides for community ownership of wells and requires SALWACO to provide rural water at cost.(UNECA 2007; FAO 2005b).

The 2008 Bumbuna Watershed Management Authority and the Bumbuna Conservation Area Act created the Bumbuna Watershed Management Authority to promote sustainable land-use practices and environmental management in the Bumbuna Watershed and the Bumbuna Conservation Area to protect the flora and fauna and address environmental and social needs associated with the operation of the Bumbuna Hydroelectric Dam (GOSL 2008b).

In an initial step toward development of a new legal framework, the government adopted a National Water Supply and Sanitation Policy in 2009. Objectives addressed in the policy include: (1) to regulate the use of water and ensure that it is managed to meet the needs of socioeconomic development and the needs of the environment in a sustainable manner; (2) to review existing laws on grant of water rights, pollution control, catchment management, and conflict resolution; and (3) to establish a Water Resources Council to regulate and manage the utilization of the water resources for socioeconomic development and sustainability of the environment at national, river basin, district, community, and international levels. The government will also embark on river basin planning, prepare standards for raw water and effluent, encourage private participation in water resources management, and institute mechanisms for collaboration and coordination in water resources management (UNECA 2007; World Bank and AfDB 2010).

TENURE ISSUES

Little information is available about Sierra Leone’s customary laws regarding water. Under customary law common to other West African countries, water is considered a communal resource. Use rights are subject to recognition of the rights of others to the resource, and preservation of the water’s quality. If water is abundant, a landholder may claim rights to a stream or other water source on his or her land. The individualization of land rights tends to include some measure of individualization of water rights (Meinzen-Dick and Nkonga 2007; Sarpong n.d.).

The 2001 SALWACO Act permits SALWACO to extract water from surface and groundwater sources in order to provide water services to the population. SALWACO is required to provide water at cost (GOSL 2001).

GOVERNMENT ADMINISTRATION AND INSTITUTIONS

Sierra Leone does not have a single, central body charged with managing the country’s water resources. Instead, at least nine agencies have responsibilities for water management. The parastatal Guma Water Company is responsible for supplying water to Freetown and its environs, and the Sierra Leone Water Company (SALWACO) and Water Supply Division are responsible for water supply in all other areas of the country. The companies and Water Supply Division are under the jurisdiction of the Ministry of Energy and Water Resources. The Environmental Health and Sanitation Department within the Ministry of Health and Sanitation is responsible for rural and urban water supply and sanitation (FAO 2005b; UNECA 2007).

The Land and Water Development Division within the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry, and Food Security is responsible for development of an irrigation and drainage strategy and collecting data on surface and groundwater resources. The National Power Authority under the Ministry of Energy and Water Resources is responsible for planning, development, use, and conservation of power, including hydropower. The Department of Environment within the Ministry of Lands, Country Planning, and Environment is responsible for mitigating the impact of natural resource use on water resources (FAO 2005b; UNECA 2007).

The Ministry of Local Government and Community Development is charged with building the capacity of districts and towns to provide government services, including water supply in rural areas. The Ministry of Planning and Economic Development is responsible for national development objectives, including the use of water in other sectors (UNECA 2007).

GOVERNMENT REFORMS, INTERVENTIONS AND INVESTMENTS

In its PRSP II (2008–2012), the government identifies the need to improve and extend irrigation systems in order to increase agricultural productivity. The joint review of the strategy by the World Bank and African Development Bank notes the country’s significant rainfall and encourages development of rainfed agriculture and diversification of crops as short- and medium-term alternatives to longer-term investments in irrigation and irrigated agriculture (GOSL 2009a; World Bank and AfDB 2010).

In 2005, the government commenced a 5-year, US $32 million Sustainable Land and Water Resources Development Project. The project, which concentrates on the development of inland valley swamps suitable for rice and vegetable production, supports the development of small-scale and community irrigation and strengthening of institutional capacity to manage water resources. The project works primarily through women’s farming organizations. A report of the project’s achievements is not yet available (GOSL 2005).

In February 2009, the government of Sierra Leone approved a National Water and Sanitation Policy. The aim of the policy is make potable water available to as many people as possible through decentralized delivery of safe drinking water and sanitation services in urban and rural areas. The policy targets high population density areas, including large villages (World Bank and AfDB 2010).

DONOR INTERVENTIONS AND INVESTMENTS

The World Bank is funding the 7-year US $47 million Power and Water Project to improve sustainable access to essential power, rural water supply and sanitation, and urban solid waste management services. As of the FY09 SOPE Review, the project had provided 64,000 people with access to improved water supply, and 25,000 with access to adequate sanitation, which represents 60% of the end-of-project target (World Bank 2009b; World Bank 2009g).

Trees and Forests

RESOURCE QUANTITY, QUALITY, USE AND DISTRIBUTION

An estimated 39% of Sierra Leone is forested, with most primary forest land located on mountains and hillsides and in isolated reserves. Tropical rain forests are found in the Eastern Province and Western Area; moist, semi-deciduous forests are found in the central and southern parts of the country. The country also has swamp and mangrove forests and savanna woodlands. Twenty-two percent of the forests are in 48 forest reserves and conservation areas; 1% is on chiefdom land but managed by the Forest Division; and 23% are within a wetland and marine ecosystem protected areas (Chemonics et al. 2007; ARD 2010).

Primary threats to forest resources include the population’s dependence on fuelwood for energy, slash-and-burn agricultural practices, urban expansion, industrial and artisanal mining, and illegal logging. These practices place tremendous pressure on forests located inside and outside reserves. The government’s capacity to manage the forests is complicated by an outdated policy and legal framework, limited institutional capacity, and lack of funding. Between 1990 and 2005, the country lost about 18% of its forests, and deforestation is estimated to be continuing at about 0.7% per year. The country has no reforestation policy (Lepizig 1996; Chemonics et al. 2007; World Bank 2009a; ARD 2010).

The timber industry does not figure prominently in the national economy, and official statistics often do not indicate any timber exports. However, fees collected on chainsaw operations reported sales of about 1200 cubic meters of timber to 11 different countries in 2005–06. The government responded to concerns raised over lack of a regulatory framework to manage the exploitation of forest reserves by imposing a ban on timber exports in 2008. In early 2010, the government lifted the ban as to the exploitation, processing and transportation of timber for the domestic market. The ban on timber exports remains in effect, but timber that was impounded at the time the ban was imposed in 2008 is permitted to be exported, subject to verification of its origin and a US $10,000 tax per container (an increase from US $1000 per container) (Ford 2008; Sierra Express Media 2010).

LEGAL FRAMEWORK

The 1998 Forest Act governs forestry practices and emphasizes sustainable forestry management. The Forest Act creates several categories of forest: classified forest, national protection forests, community forests, and protected forests, although the distinction between these categories is not clear. The Forest Act prohibits the cutting, burning, uprooting, or destruction of trees in protected areas or trees that have been declared protected. The chief conservator/director of forests can issue a license or concession to fell and extract trees in protected areas. Environmental aspects of forestry are addressed in the 2008 National Environment Protection Act (Baker et al. 2003; Chemonics et al. 2007).

Sierra Leone adopted a new Forestry Policy in 2004. The policy supports the development and exploitation of the forests and wildlife of Sierra Leone in a sustainable manner for the material, cultural and aesthetic benefit of the people of Sierra Leone in particular and mankind in general. The policy includes sections relating to community forests, private forests, forest economy, bioprospecting, and wildlife. The policy strengthens the role of the Forestry Division to manage forests and wildlife in line with the decentralization policy, and empowers communities to manage natural resources together with the government. The policy notes linkages to other sectors such as water catchments, mining, urban land, ecotourism, forest medicines and social forestry. The policy has not yet been made operational through legislation (Cemmats 2004).

TENURE ISSUES

Forests can be owned by the state or private parties, or fall within chieftaincy land. Forest land is generally subject to the tenure system governing the land classification, unless the forest has been declared a protected area. The Forestry Act of 1988 empowers the minister to declare any area to be a protected area for the purpose of conservation of soil, water, flora, and fauna (Chemonics et al. 2007).

The current extent of state-owned forestland is unknown. The state owns most of the land designated as forest reserves and nationally protected areas, but some percentage of land is also privately held or within chieftaincy land (FAO 2005a; Chemonics et al. 2007).

GOVERNMENT ADMINISTRATION AND INSTITUTIONS

The Forestry Division of the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Food Security (MAFFS) is responsible for forest management and biodiversity conservation. The National Commission on Environment and Forestry (NaCEF) was created in 2005 and is responsible for: managing the country’s natural and environmental resources, advising the Ministry on policy, project implementation, environmental monitoring, and setting priorities. The Forestry and Wildlife divisions within NaCEF are responsible for natural forest management, management of forest plantations, and management of rangeland and national parks. There is considerable overlap in environmental responsibilities of the NaCEF and other ministries, such as the Ministry of Agriculture and Food Security, Ministry of Lands and Country Planning, Ministry of Works and Technical Maintenance, and Ministry of Mineral Resources (Chemonics et al. 2007; UNDP 2007).

The 2008 National Environmental Protection Act established a National Environment Protection Board to facilitate coordination among Ministries, agencies, and local authorities in all areas relating to environmental protection. In 2008, the government established the Sierra Leone Environmental Protection Agency (SLEPA) within the Ministry of Lands, Country Planning and Environment as the agency responsible for environmental management (CIEN News 2008).

The Chief Conservator of Forests (CCF) is head of the Forestry Division and is responsible for the management and protection of forest reserves, game reserves and national parks. The forests within chiefdoms are within the jurisdiction of the CCF. However, the Forestry Division often lacks the capacity necessary to perform its duties, and the chieftaincy system often manages forest resources (UNDP 2007).

GOVERNMENT REFORMS, INTERVENTIONS AND INVESTMENTS

Sierra Leone’s PRSP II (2008–2012) acknowledges the importance of sustainable management of Sierra Leone’s natural resources, including its forests, for achieving future economic growth. The strategy emphasizes the need to strengthen the linkages between poverty reduction and management of the environment, and to map and inventory the natural high forests in Sierra Leone. The government plans to create a restructured forestry division and to explore possibilities for investment in sustainable financing mechanisms such as carbon markets and trading schemes. The government also plans to give incentives to stimulate economic and social development through the establishment of community woodlots and investment in sustainable forest management schemes (GOSL 2009a; GOSL 2009c).

The World Bank is supporting the government’s 5-year (2010–2015) US $24 million Biodiversity Conservation Project. The project will emphasize building the capacity of governmental institutions and personnel to carry out their mandates effectively through engaging local communities, local government, and other key stakeholders to participate in effective conservation planning and management at three priority conservation sites. The project is designed to contribute to the PRSP II by taking steps to halt deforestation, biodiversity loss and land degradation; develop and implement strategies that address environment at the national level; and build capacity of communities to manage protected areas (World Bank 2010).

The Forestry Division, NaCEF, seven chiefdoms, and several international conservation groups joined in the establishment of a 2008–2012 management plan for the Gola Forest. The Gola Forest covers 75,000 hectares in the southeastern section of the country and has been under pressure from commercial logging, large-scale mining, and plantation interests. The forest is one of the top priority sites for conservation in West Africa, with 14 globally threatened bird species, 47 species of large mammals, (including 11 primates), and at least 74 endemic plant species. The area is also home to about 130,000 people. The management plan includes components relating to conservation and protection, community outreach and development (including utilization of non-timber forest products and development of small-scale tourism), and research and monitoring (GOSL 2007c; Alieu 2001; CI n.d.).

DONOR INTERVENTIONS AND INVESTMENTS

USAID designed the Creating an Enabling Policy Environment in Sierra Leone (CEPESL) Project to support the Government of Sierra Leone in developing an enabling environment for improved natural resources management. The project plans to establish the enabling policy conditions necessary in order to achieve sustainable and productive natural resources system in Sierra Leone. USAID/Sierra Leone will provide support for the establishment of participatory, equitable and transparent governance structures, policies, laws, regulations and administrative practices that are necessary for the sustainable management of natural resources (ARD 2010).

USAID’s 4-year, US $13.2 million Promoting Agriculture, Governance and Environment (PAGE) project is implemented by a consortium led by ACDI/VOCA, in partnership with Associates in Rural Development (ARD) and World Vision. The project is working with the Forestry Division, district councils, traditional authorities, and communities in Koinadugu, Kono, Kailahun, and Kenema districts to pilot forest co-management. These pilots are providing a useful learning opportunity to help inform the ongoing policy, legal and regulatory reform process, and to strengthen efforts to improve on-the-ground management of Sierra Leone’s forest resources (ARD 2010).

The United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), Global Environment FaciltyFacility (GEF), the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), and other partners are implementing a 6-year (2008–2013) US $1.2 million project providing the government with capacity-building in support of sustainable natural resource management. The project includes components for training in community forest management and reform of the regulatory framework governing natural resources (UNDP 2007).

Trees and Forests

RESOURCE QUANTITY, QUALITY, USE AND DISTRIBUTION

An estimated 39% of Sierra Leone is forested, with most primary forest land located on mountains and hillsides and in isolated reserves. Tropical rain forests are found in the Eastern Province and Western Area; moist, semi- deciduous forests are found in the central and southern parts of the country. The country also has swamp and mangrove forests and savanna woodlands. Twenty-two percent of the forests are in 48 forest reserves and conservation areas; 1% is on chiefdom land but managed by the Forest Division; and 23% are within a wetland and marine ecosystem protected areas (Chemonics et al. 2007; ARD 2010).

Primary threats to forest resources include the population’s dependence on fuelwood for energy, slash-and-burn agricultural practices, urban expansion, industrial and artisanal mining, and illegal logging. These practices place tremendous pressure on forests located inside and outside reserves. The government’s capacity to manage the forests is complicated by an outdated policy and legal framework, limited institutional capacity, and lack of funding. Between 1990 and 2005, the country lost about 18% of its forests, and deforestation is estimated to be continuing at about 0.7% per year. The country has no reforestation policy (Lepizig 1996; Chemonics et al. 2007; World Bank 2009a; ARD 2010).

The timber industry does not figure prominently in the national economy, and official statistics often do not indicate any timber exports. However, fees collected on chainsaw operations reported sales of about 1200 cubic meters of timber to 11 different countries in 2005–06. The government responded to concerns raised over lack of a regulatory framework to manage the exploitation of forest reserves by imposing a ban on timber exports in 2008. In early 2010, the government lifted the ban as to the exploitation, processing and transportation of timber for the domestic market. The ban on timber exports remains in effect, but timber that was impounded at the time the ban was imposed in 2008 is permitted to be exported, subject to verification of its origin and a US $10,000 tax per container (an increase from US $1000 per container) (Ford 2008; Sierra Express Media 2010).

LEGAL FRAMEWORK

The 1998 Forest Act governs forestry practices and emphasizes sustainable forestry management. The Forest Act creates several categories of forest: classified forest, national protection forests, community forests, and protected forests, although the distinction between these categories is not clear. The Forest Act prohibits the cutting, burning, uprooting, or destruction of trees in protected areas or trees that have been declared protected. The chief conservator/director of forests can issue a license or concession to fell and extract trees in protected areas. Environmental aspects of forestry are addressed in the 2008 National Environment Protection Act (Baker et al. 2003; Chemonics et al. 2007).

Sierra Leone adopted a new Forestry Policy in 2004. The policy supports the development and exploitation of the forests and wildlife of Sierra Leone in a sustainable manner for the material, cultural and aesthetic benefit of the people of Sierra Leone in particular and mankind in general. The policy includes sections relating to community forests, private forests, forest economy, bioprospecting, and wildlife. The policy strengthens the role of the Forestry Division to manage forests and wildlife in line with the decentralization policy, and empowers communities to manage natural resources together with the government. The policy notes linkages to other sectors such as water catchments, mining, urban land, ecotourism, forest medicines and social forestry. The policy has not yet been made operational through legislation (Cemmats 2004).

TENURE ISSUES

Forests can be owned by the state or private parties, or fall within chieftaincy land. Forest land is generally subject to the tenure system governing the land classification, unless the forest has been declared a protected area. The Forestry Act of 1988 empowers the minister to declare any area to be a protected area for the purpose of conservation of soil, water, flora, and fauna (Chemonics et al. 2007).

The current extent of state-owned forestland is unknown. The state owns most of the land designated as forest reserves and nationally protected areas, but some percentage of land is also privately held or within chieftaincy land (FAO 2005a; Chemonics et al. 2007).

GOVERNMENT ADMINISTRATION AND INSTITUTIONS

The Forestry Division of the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Food Security (MAFFS) is responsible for forest management and biodiversity conservation. The National Commission on Environment and Forestry (NaCEF) was created in 2005 and is responsible for: managing the country’s natural and environmental resources, advising the Ministry on policy, project implementation, environmental monitoring, and setting priorities. The Forestry and Wildlife divisions within NaCEF are responsible for natural forest management, management of forest plantations, and management of rangeland and national parks. There is considerable overlap in environmental responsibilities of the NaCEF and other ministries, such as the Ministry of Agriculture and Food Security, Ministry of Lands and Country Planning, Ministry of Works and Technical Maintenance, and Ministry of Mineral Resources (Chemonics et al. 2007; UNDP 2007).

The 2008 National Environmental Protection Act established a National Environment Protection Board to facilitate coordination among Ministries, agencies, and local authorities in all areas relating to environmental protection. In 2008, the government established the Sierra Leone Environmental Protection Agency (SLEPA) within the Ministry of Lands, Country Planning and Environment as the agency responsible for environmental management (CIEN News 2008).

The Chief Conservator of Forests (CCF) is head of the Forestry Division and is responsible for the management and protection of forest reserves, game reserves and national parks. The forests within chiefdoms are within the jurisdiction of the CCF. However, the Forestry Division often lacks the capacity necessary to perform its duties, and the chieftaincy system often manages forest resources (UNDP 2007).

GOVERNMENT REFORMS, INTERVENTIONS AND INVESTMENTS

Sierra Leone’s PRSP II (2008–2012) acknowledges the importance of sustainable management of Sierra Leone’s natural resources, including its forests, for achieving future economic growth. The strategy emphasizes the need to strengthen the linkages between poverty reduction and management of the environment, and to map and inventory the natural high forests in Sierra Leone. The government plans to create a restructured forestry division and to explore possibilities for investment in sustainable financing mechanisms such as carbon markets and trading schemes. The government also plans to give incentives to stimulate economic and social development through the establishment of community woodlots and investment in sustainable forest management schemes (GOSL 2009a; GOSL 2009c).

The World Bank is supporting the government’s 5-year (2010–2015) US $24 million Biodiversity Conservation Project. The project will emphasize building the capacity of governmental institutions and personnel to carry out their mandates effectively through engaging local communities, local government, and other key stakeholders to participate in effective conservation planning and management at three priority conservation sites. The project is designed to contribute to the PRSP II by taking steps to halt deforestation, biodiversity loss and land degradation; develop and implement strategies that address environment at the national level; and build capacity of communities to manage protected areas (World Bank 2010).

The Forestry Division, NaCEF, seven chiefdoms, and several international conservation groups joined in the establishment of a 2008–2012 management plan for the Gola Forest. The Gola Forest covers 75,000 hectares in the southeastern section of the country and has been under pressure from commercial logging, large-scale mining, and plantation interests. The forest is one of the top priority sites for conservation in West Africa, with 14 globally threatened bird species, 47 species of large mammals, (including 11 primates), and at least 74 endemic plant species. The area is also home to about 130,000 people. The management plan includes components relating to conservation and protection, community outreach and development (including utilization of non-timber forest products and development of small-scale tourism), and research and monitoring (GOSL 2007c; Alieu 2001; CI n.d.).

DONOR INTERVENTIONS AND INVESTMENTS

USAID designed the Creating an Enabling Policy Environment in Sierra Leone (CEPESL) Project to support the Government of Sierra Leone in developing an enabling environment for improved natural resources management. The project plans to establish the enabling policy conditions necessary in order to achieve sustainable and productive natural resources system in Sierra Leone. USAID/Sierra Leone will provide support for the establishment of participatory, equitable and transparent governance structures, policies, laws, regulations and administrative practices that are necessary for the sustainable management of natural resources (ARD 2010).

USAID’s 4-year, US $13.2 million Promoting Agriculture, Governance and Environment (PAGE) project is implemented by a consortium led by ACDI/VOCA, in partnership with Associates in Rural Development (ARD) and World Vision. The project is working with the Forestry Division, district councils, traditional authorities, and communities in Koinadugu, Kono, Kailahun, and Kenema districts to pilot forest co-management. These pilots are providing a useful learning opportunity to help inform the ongoing policy, legal and regulatory reform process, and to strengthen efforts to improve on-the-ground management of Sierra Leone’s forest resources (ARD 2010).

The United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), Global Environment FaciltyFacility (GEF), the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), and other partners are implementing a 6-year (2008–2013) US $1.2 million project providing the government with capacity-building in support of sustainable natural resource management. The project includes components for training in community forest management and reform of the regulatory framework governing natural resources (UNDP 2007).

Minerals

RESOURCE QUANTITY, QUALITY, USE AND DISTRIBUTION

Sierra Leone has substantial mineral resources, including diamonds, bauxite, iron ore gold, cement, ilmenite, and rutile. The sector provides 15–18% of GDP and 90% of export earnings. Sierra Leone’s mineral sector has three sub-sectors: (1) large-scale production of non-precious minerals – bauxite and rutile; (2) large-scale production of precious minerals, e.g, diamonds; and (3) artisanal and small-scale production of precious minerals – primarily diamonds and, to a lesser extent, gold. Large-scale mining operations in Sierra Leone are foreign-owned (e.g., Sierra Rutile Ltd. in rutile, Sierra Minerals Ltd. in bauxite, and Koidu Holdings Ltd. in diamonds). Very few Sierra Leoneans have the financial capacity to fund prospecting and exploration activities (Bermudez-Lugo 2009; Chemonics et al. 2007; USGS 2008; Hooge 2008).

Oil reserves have been discovered off Sierra Leone’s coast. The extent of oil and its commercial viability is not expected to be determined until 2011. Exploration has also suggested that the country’s reserves of iron ore are potentially much larger than previously contemplated (World Bank and AfDB 2010).

Before the civil war, diamonds were the country’s most significant resource. Sierra Leone’s peak diamond production came in the 1960s. During the civil war, mining was limited to artisanal mining, which warlords controlled and used to purchase arms and supplies. The post-war period has brought significant increases in sector activity. Diamond production doubled in the period between 2004 and 2007, and accounted for 70% of all mineral export earnings and about 54% of total export earnings in 2006. Gold production increased by 199% between 2006 and 2007. As of 2006, the resumption of bauxite and rutile (titanium dioxide) mining increased export earnings by 39% (Chemonics et al. 2007; USGS 2008).

Loss of revenue from unrecorded sales in diamonds is unknown. Official value of annual exports in 2006, as reported by the Bank of Sierra Leone, was US $125 million, or about one-third of the US $400 million estimated per year by a local NGO. There reportedly remain large areas of potentially diamondiferous gravel still unprocessed (Chemonics et al. 2007; USGS 2008).

The widespread practice of artisanal mining has imposed significant cumulative impacts on the country’s forests and biodiversity. Mining has caused loss of vegetation, soil erosion, and contamination of water sources. The pollution of surface water by runoff from earthmoving and other mining activities is significant, and heaps of mine spoils, tailings, and construction have disturbed established patterns of river drainage, leading to flooding and erosion. Mining activities, particularly in the eastern and southern regions, have resulted in deforestation and degradation of around 80,000–120,000 hectares of land, and the destruction continues without plans for land reclamation (UNDP 2007; Chemonics et al. 2007).

Massive corruption in Sierra Leone’s diamond industry played a significant role in creating the environment for political collapse. The country’s leader from 1968 to 1985, Siaka Stevens, personally controlled the lucrative sector, overseeing the mass diversion of revenue to the pockets of favored elites. By the end of Stevens’ tenure, the economy was entirely criminalized and had all but collapsed. The situation did not improve under his successor, the military leader Joseph Momoh. The looting of natural resources for personal gain marginalized much of the population, undermined the government’s legitimacy, and weakened its capacity to maintain peace and stability (UNEP 2009).

LEGAL FRAMEWORK

The 2009 Mines and Minerals Act and the 2009 Mines and Minerals Regulations regulate the mining sector. The 2009 legislation is the result of a 3-year effort to reform the legal framework governing the minerals sector. The new Act: (1) addresses previously unregulated areas of health and safety, environmental protection, and community development; (2) tightens rules for administrators and mineral rights holders, including application and reporting requirements; (3) promotes investment and minerals sector development by ensuring security of tenure and preventing companies from holding land under license without demonstrable activities; and (4) rebalances fiscal benefits among companies, communities, and the government (GOSL 2010; GOSL 2009d).

The 2007 Diamond Cutting and Polishing Act provides for the licensing and control of diamond processing. A license issued under the Act allows the licensee to buy, deal in, export, and import diamonds, in addition to cutting and polishing. The Act provides that activities must be in compliance with the Kimberly Process, and requires payment of 3% of the value of the rough diamonds and duty in the amount of the difference of the certified value of the unpolished and the cut and polished diamonds to the government ministry or revenue authority (GOSL 2007; USGS 2008).

In 2003, the government adopted a Core Mineral Policy designed to revive the mining sector following the end of the war. The policy adopts a sustainable development approach that considers the needs and interests of mining-affected stakeholders. The Core Minerals Policy was revised in 2008–2009 and the principles incorporated in the 2009 Mines and Minerals Act (GOSL 2009d; Hooge 2008).

The 2001 Petroleum Exploration and Production Act regulates the petroleum sector. The Act establishes the Petroleum Resources Unit, which is under the authority of the President and is headed by a Director-General (Cemmats 2004).