Research shows that strengthening women’s land and resource rights has a striking and positive impact on women’s empowerment. And yet, across much of the world, formal and informal laws and customs hinder women’s access to land and resources, leaving them unable to fulfill their full potential as agents of economic and social change.

USAID is helping to address this longstanding inequity through its Mobile Applications to Secure Tenure (MAST), a blend of participatory mapping approaches and flexible technology tools that allows communities to document and secure their land and resource rights using a smartphone. MAST’s participatory mapping methodology emphasizes on-the-ground engagement and extensive training to empower citizens as data collectors and administrators and build their capacity to maintain land information and manage their land and resources.

MAST engages local communities—with specific focus to the inclusion of women and youth as trusted local community members—who are trained to use maps and mobile devices to identify and record individual and communal land boundaries, land use, and ownership information. Mapping and information gathering takes place in the presence of land rights’ holders and neighbors and also engages marginalized groups, such as pastoralists.

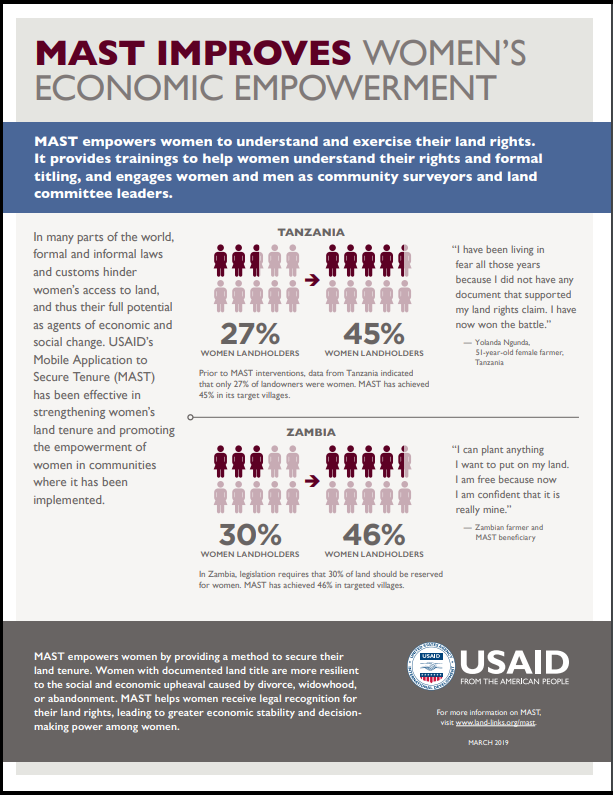

Across several countries where it has been deployed, MAST has already been effective in strengthening women’s land tenure and promoting the empowerment of women in communities where it has been implemented. In Tanzania, for example, the Land Tenure Assistance (LTA) activity employed a MAST approach to help women register their rights at the same rate as their male counterparts during the issuance of more than 100,000 customary land certificates (CCROs). In Zambia, the Integrated Land and Resource Governance (ILRG) project used MAST to ensure that half of all land documents in the project area were issued to women. And in Mozambique, the ILRG project implemented activities to help shift attitudes to be more supportive of women’s ownership of land.

In March, USAID convened a learning exchange with partners from Tanzania, Mozambique, and Zambia who are actively using a MAST approach to document community land rights. Participants attending the exchange discussed the role of MAST in strengthening women’s land tenure and resource rights and how MAST might be made an even more powerful tool for promoting women’s empowerment. Here are five things that we learned from the discussion:

Meaningfully and directly engage women as project implementers

MAST allows for the direct involvement of citizens to map and register their land. Implementers in Tanzania, Mozambique, and Zambia have all found that including women in training, discussions, and mapping can help ensure that their rights are accounted for during the registration process. Recruiting women as para-surveyors and dispute adjudicators ensures that their perspectives and land claims are taken into account, while also providing them with short-term employment, transferable skills, and stronger feelings of confidence and empowerment. Although gender inequalities and gender norms that govern the behavior of girls and women (such as the division of household responsibilities) can make it difficult to recruit women to implement MAST, it is critical to encourage and promote their participation in these important community processes.

Intentionally cultivate women’s participation in meetings and training to promote their engagement

A key component of the MAST approach is training and actively engaging community members in discussions about community land resources, land use planning, land laws, and the importance of securing land rights. These trainings and discussions, which provide an important foundation for any mapping process, build important community awareness and buy-in to the process that is necessary for systematic land documentation. They also ensure greater participation and uptake by community members. Implementers have found that without employing specific means to intentionally engage women, these important, initial community sensitization meetings that seek to clarify land holdings and traditional rules are often dominated by men. Holding separate, female-only trainings can provide more space for women and youth to meaningfully engage with the MAST process and share their own thoughts, questions, and concerns.

Tailor the engagement of women to the local context

Where MAST has been implemented in Tanzania, Mozambique, and Zambia, local groups and communities maintain their own customs, matrilineal or patrilineal inheritance processes, familial structures, and class dynamics. Women often have responsibilities that are unique from men, which include childcare duties and domestic household management. Hence, it is important throughout the mapping process to engage women in ways that adequately account for their unique social roles, needs, and schedules. In addition, it is important to understand traditional customs and social rules that might prevent women from accessing and owning land. In some communities, for example, traditional customs and norms prohibit women from owning land in their own right. In these communities, encouraging joint registration between spouses (where both the husband and wife have their names listed on a land certificate) may be the best option to provide women with some level of tenure security.

Account for the time and effort required to change attitudes during project implementation

Implementers across all three countries stressed that changing attitudes toward more positive perceptions of women’s land ownership takes time and effort. Since the laws and regulations governing women’s land ownership are not always known or well understood, it can take significant time to educate communities about these rules, which include the nuances of how strengthening women’s property rights can benefit entire households and communities. Multiple training sessions on the same topic might be required. Although this deliberate engagement can lengthen the time frame for land documentation using a MAST approach as compared to on-demand, targeted, and rapid land documentation, education is likely one of the most critical components to securing women’s land rights for the long-term.

Engage men as champions of women’s participation and equality

It is well known that teaching men and boys to become champions for gender equality and women’s empowerment is essential to achieving gender-related development objectives and long-lasting social change. In fact, one of the eight operating principles listed in USAID’s Gender Equality and Women’s Empowerment Policy is to engage men and boys. Similarly, MAST implementers have found that cultivating male champions to support women’s participation in MAST, especially during early phases of the community mapping process, can help ensure greater and more meaningful participation by women. In addition, because MAST often challenges traditional gender norms around land ownership, there is a risk that women’s participation in the MAST process may encounter resistance in communities that might traditionally prevent women from accessing and owning land. Male champions, especially those in leadership positions, have been helpful in transforming traditional attitudes to promote more active participation of women and helping communities avoid pushback toward women and girls during and after the mapping process.

Since 2015, USAID has worked in rural Iringa District, the heart of Tanzania’s southern agricultural region, to strengthen land rights and systematically address the lack of land documentation. Over the past five years, USAID/Tanzania’s Land Tenure Activity (LTA) helped villages and the district land office demarcate more than 70,000 land parcels and register more than 60,000 land certificates (known as CCROs), all using USAID’s digital

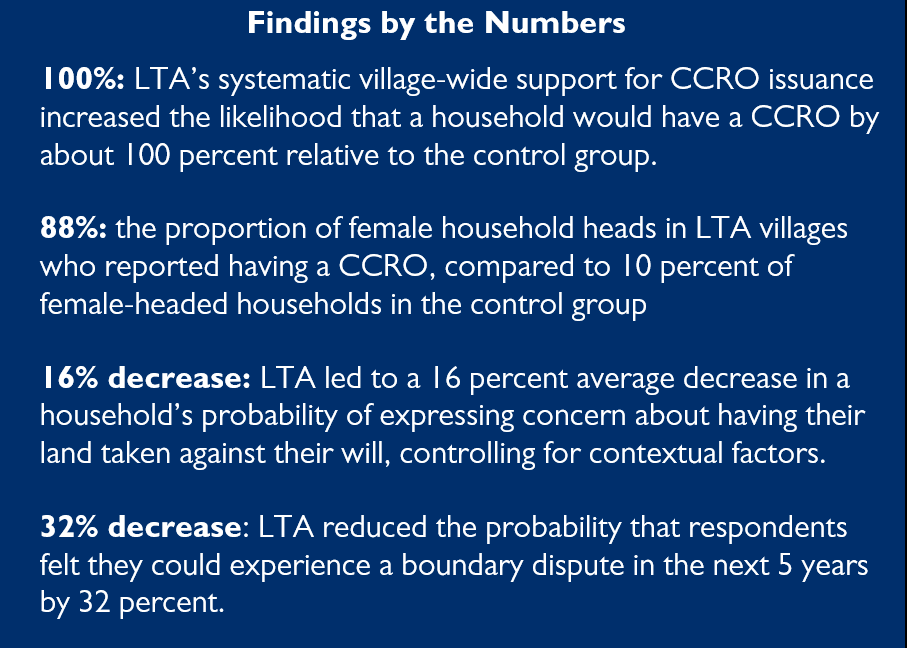

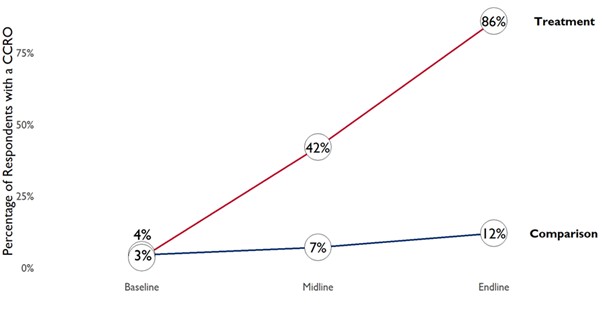

Since 2015, USAID has worked in rural Iringa District, the heart of Tanzania’s southern agricultural region, to strengthen land rights and systematically address the lack of land documentation. Over the past five years, USAID/Tanzania’s Land Tenure Activity (LTA) helped villages and the district land office demarcate more than 70,000 land parcels and register more than 60,000 land certificates (known as CCROs), all using USAID’s digital  The impact evaluation of LTA has helped USAID measure the activity’s effect on land-related outcomes and understand how systematic certification of customary land rights affects smallholder farmers’ tenure security, investment decisions, empowerment, and broader livelihoods. With increasing land pressures and widespread concerns about land grabbing, knowing the impacts of formalized customary use rights is relevant to both farmers and policymakers.

The impact evaluation of LTA has helped USAID measure the activity’s effect on land-related outcomes and understand how systematic certification of customary land rights affects smallholder farmers’ tenure security, investment decisions, empowerment, and broader livelihoods. With increasing land pressures and widespread concerns about land grabbing, knowing the impacts of formalized customary use rights is relevant to both farmers and policymakers.

Tenure security improved for both men and women, and to a greater extent for female relative to male households heads. The evaluation also found a substantial increase in tenure security for female primary spouses supported by LTA. These improvements are especially important in the rural Tanzanian context, where women often have a harder time claiming and defending their land rights or exercising control over land decisions. Based on the evaluation results, USAID/Tanzania’s support for formalized customary land documentation seems to have not only expanded people’s access to CCROs but also led to more equitable access to land documentation in ways that allay gender-based concerns around land grabbing.

Tenure security improved for both men and women, and to a greater extent for female relative to male households heads. The evaluation also found a substantial increase in tenure security for female primary spouses supported by LTA. These improvements are especially important in the rural Tanzanian context, where women often have a harder time claiming and defending their land rights or exercising control over land decisions. Based on the evaluation results, USAID/Tanzania’s support for formalized customary land documentation seems to have not only expanded people’s access to CCROs but also led to more equitable access to land documentation in ways that allay gender-based concerns around land grabbing.