As part of the Feed the Future initiative, USAID is helping the Government of Tanzania to improve communities’ understanding of land rights, support village land use planning, and clarify, document and certify property rights. USAID anticipates that this program – the Land Tenure Assistance Activity (LTA) – will reduce land-tenure related risks and lay the foundation for sustainable and inclusive agricultural investment for both smallholders and large-scale commercial investors. The program is a positive example of how a USAID investment is catalyzing innovation and partnerships for economic prosperity and self-reliance in Tanzania.

By the end of 2019, LTA is expected to have registered – for the first time – over 50,000 parcels, benefiting over 14,000 Tanzanian villagers.

At the heart of the program is USAID’s Mobile Application to Secure Tenure (MAST), a suite of innovative approaches, inclusive methods, and mobile technology tools to efficiently, transparently, and affordably document rights to land and other resources. In addition to Tanzania, USAID is working with other governments and communities to use MAST in Burkina Faso, Myanmar, and Zambia.

Evolution of MAST

These days, smartphones and tablets are everywhere, even in some of the most remote villages around the world. To leverage these technologies to meet the challenge of providing affordable, accessible land administration services to rural areas, in 2014 USAID began working with the Tanzanian government and local residents to pilot MAST in Ilalasimba, a small village in Iringa District. The initial pilot was a proof of concept – to test whether the idea of using low cost mobile technology to map and register land rights would work and could be affordably scaled-up to the rest of the country.

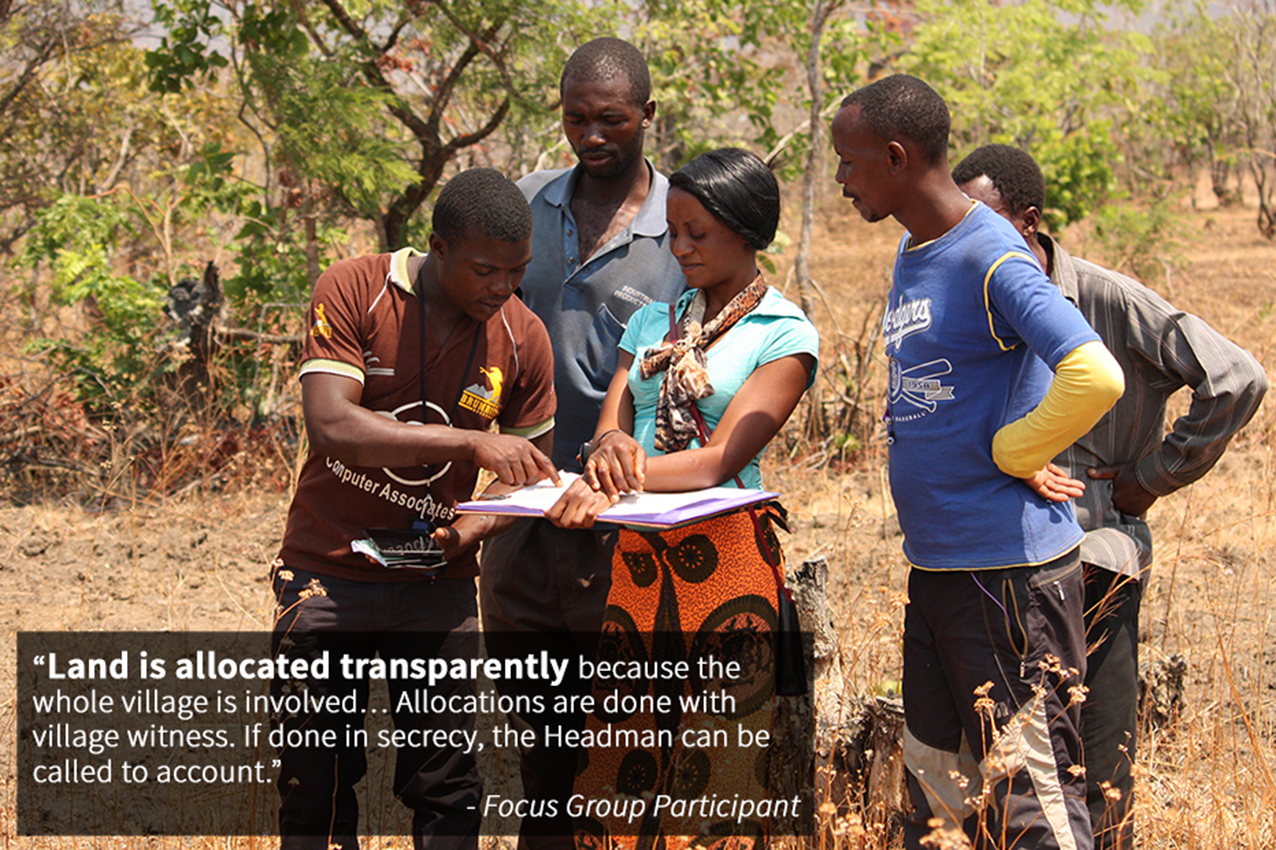

Central to the pilot was the assistance of and input from both the local government and community members themselves, in particular local youth who functioned as “trusted intermediaries,” helping to teach other villagers about MAST. Beyond just technology, the pilot project raised awareness among villagers about their land rights, with a special emphasis on women’s land rights. Only then did the project team map, record, and register those rights using MAST. As USAID/Tanzania’s Hal Carey explains, villagers were “interested and excited about [MAST] because it was an opportunity to participate in land governance…for women, it meant an opportunity to secure tenure for their children; for everyone, it meant access to finance. Everyone saw the potential, although there was some skepticism.”

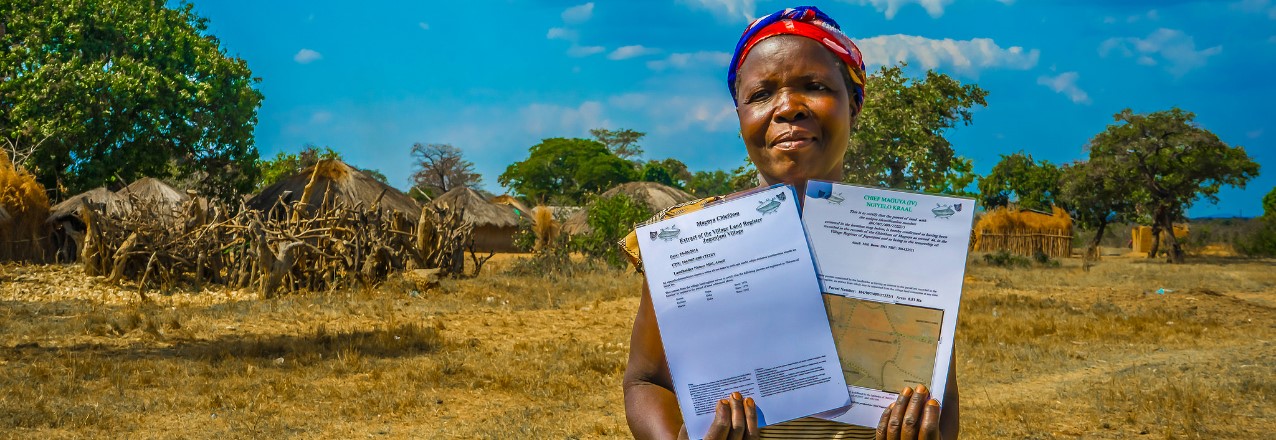

In that first village – Ilalasimba – the pilot team mapped, recorded, and registered 910 parcels using MAST, benefiting 345 families. Soon after, the District Land officials issued official land certificates – known in Tanzania as Certificates of Customary Rights of Occupancy (CCROs) – for each parcel. The number of registered parcels increased to 1139 for the second village and 1886 for the third. Importantly, despite early resistance from many men to the registration of women’s land rights, the pilot’s education, training, and outreach activities resulted in parity in land registration between men and women. For example, in Itagutwa village, 33% of the parcels were registered solely in women’s names, while 32% of parcels were registered jointly in women and men’s names.

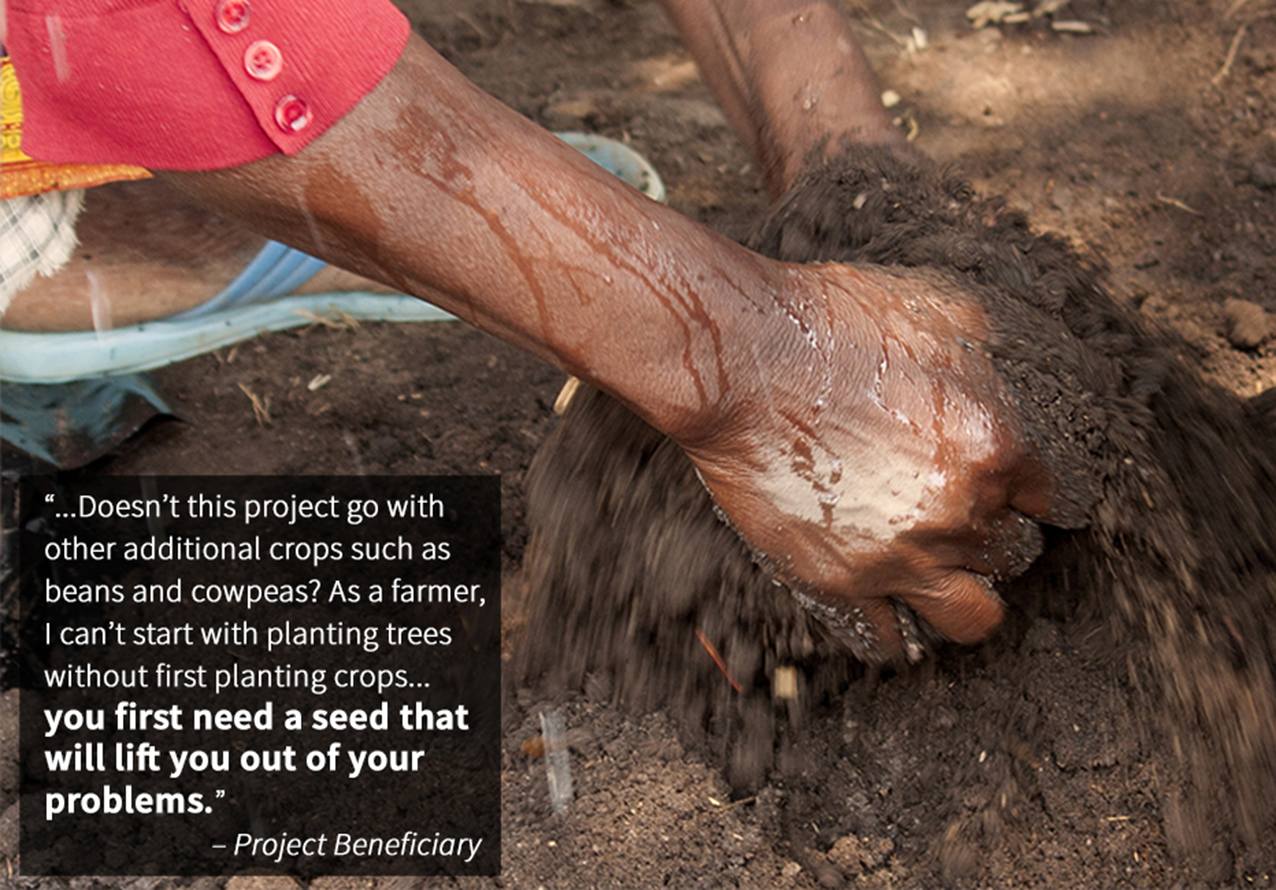

Now, with their land certificates in hand, residents of the MAST pilot villages enjoy greater clarity of their rights, including their parcel boundaries, enhanced tenure security, and stronger incentives to make long-term investments on their land. For example, families are using the certificates as collateral to invest in their businesses.

For USAID and the Tanzanian Government, the initial MAST pilot generated many lessons and produced a commitment to continue improving and scaling MAST, given its relative efficiency, low-cost, and user-friendly tools, compared with more traditional adjudication approaches that utilize labor intensive approaches and required expensive equipment and specialized inputs. The initial MAST pilot was judged a success for improving tenure security and in establishing and reinforcing participatory and transparent governance mechanisms at the village level which, in turn, have the potential to lead to greater smallholder and large-scale commercial investments in land.

USAID’s Land Tenure Assistance Activity expands MAST

Based on the success of the initial pilot, USAID launched the Land Tenure Assistance (LTA) activity in 2015 to scale-up the work to a much larger area. Under LTA, USAID has refined MAST’s technology and methods to deliver CCROs as well as village land use plans, which are a precondition for the issuance of land certificates under Tanzania’s Village Land Use Act. As Carey explains, “the [initial] tool had some shortcomings.” However, USAID “took the lessons learned from the MAST pilot and revised the application itself for more accountability…accuracy, and efficiency.”

Through 2017, the LTA program has achieved promising results, including:

- Registering 14,747 CCROs, covering 20,000 hectares of land in 13 villages;

- Empowering women to claim their land rights: 48% of all claimants were women;

- Lowering the cost per parcel from $20.57 at project inception to $7.85;

- Helping to establish 13 women’s groups and strengthen 32 others;

- Training 17,714 individuals on land tenure and property rights;

- Supporting the upgrading of 10 village registry offices;

- Creating a radio program on land registration and the LTA project on five radio stations; and

- Launching a youth sensitization program in secondary schools.

Semaly Kisamo, also from USAID/Tanzania, noted that MAST is a “very participatory process with villagers themselves participating. It’s generating ownership, sustainability, and trust… communities trust [each other] more. They are engaging and coming together to resolve issues. They are very appreciative of the project.”

The Government of Tanzania is now exploring opportunities to roll out MAST nationwide. While the Government looks to build a national land information system, which will focus first on the registration and administration of urban land, MAST offers a relatively low-cost, efficient, and user-friendly tool for formalizing customary rights in rural areas. As such, MAST provides an effective and sustainable tool that can easily be made compatible with the national land information system. It may prove beneficial to the Government in contributing to the activities focused on promoting transparency in the administration of rural lands, increasing tenure security, and ultimately enhancing the investment climate in Tanzania.

The Government recently decided that the Land Tenure Support Programme, which several European donors support in Tanzania’s Kilombero District, will use MAST and the same implementation protocols as the LTA program to support the systematic adjudication.

To learn more about MAST, see the MAST Learning Platform, a knowledge portal with documentation, tools, lessons learned, and best practices from existing MAST projects. The MAST Learning Platform also will feature upcoming MAST activities to be implemented under the USAID-supported Land Technology Solutions Project (LTS) and other USAID programs.

Since 2014,

Since 2014,

Tao Van Dang has served as the activity manager for the Participatory Coastal Spatial Planning and Mangrove Governance project in Vietnam since 2015. With more than 20 years of project management experience, particularly in non-governmental organizations, Dang has overseen mangrove re-forestation and disaster preparedness projects throughout Vietnam.

Tao Van Dang has served as the activity manager for the Participatory Coastal Spatial Planning and Mangrove Governance project in Vietnam since 2015. With more than 20 years of project management experience, particularly in non-governmental organizations, Dang has overseen mangrove re-forestation and disaster preparedness projects throughout Vietnam.

Catherine (Kitty) Courtney has more than 25 years of international and domestic experience in marine and coastal management, climate change adaptation and coastal community resilience.

Catherine (Kitty) Courtney has more than 25 years of international and domestic experience in marine and coastal management, climate change adaptation and coastal community resilience.

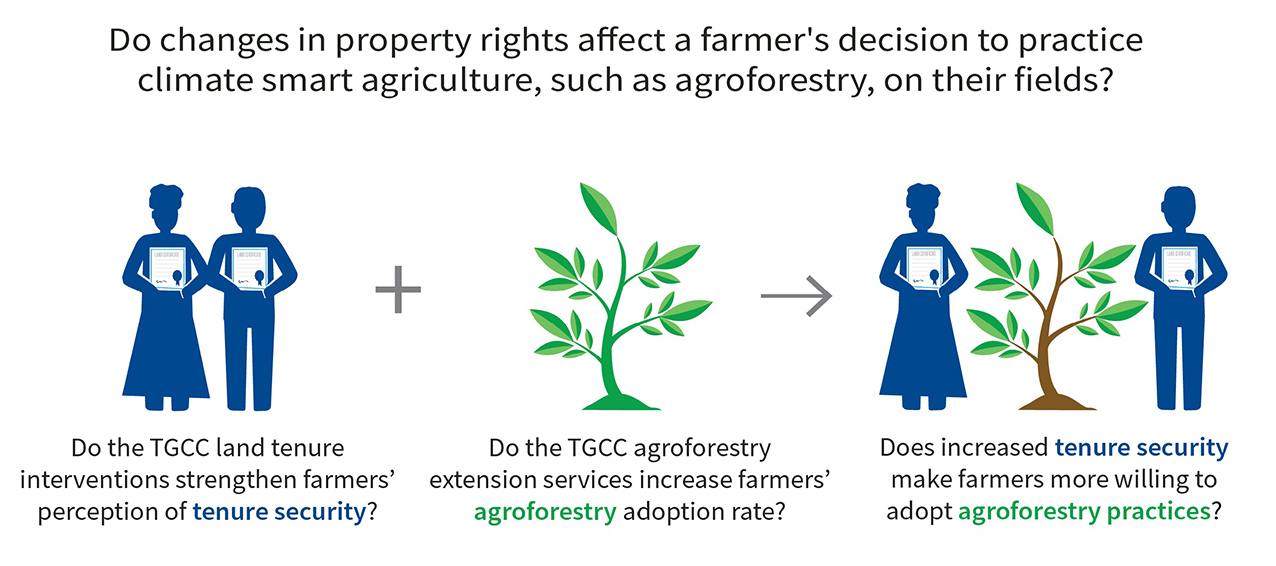

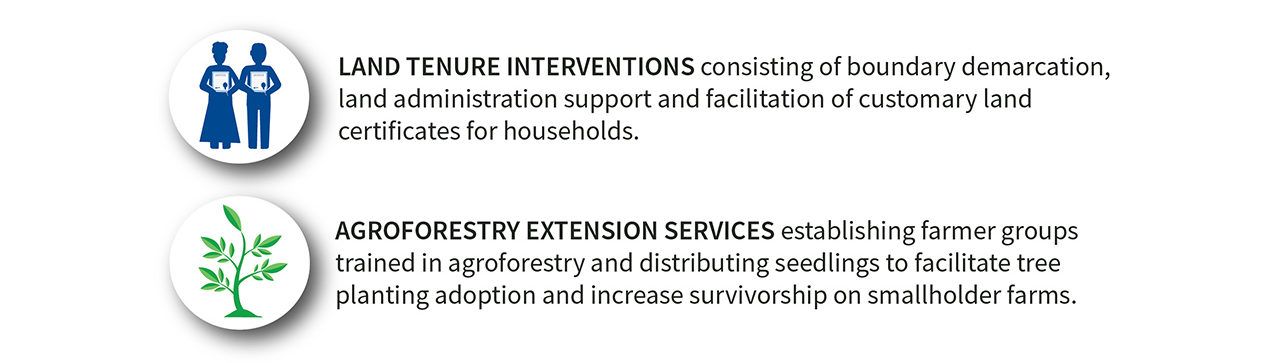

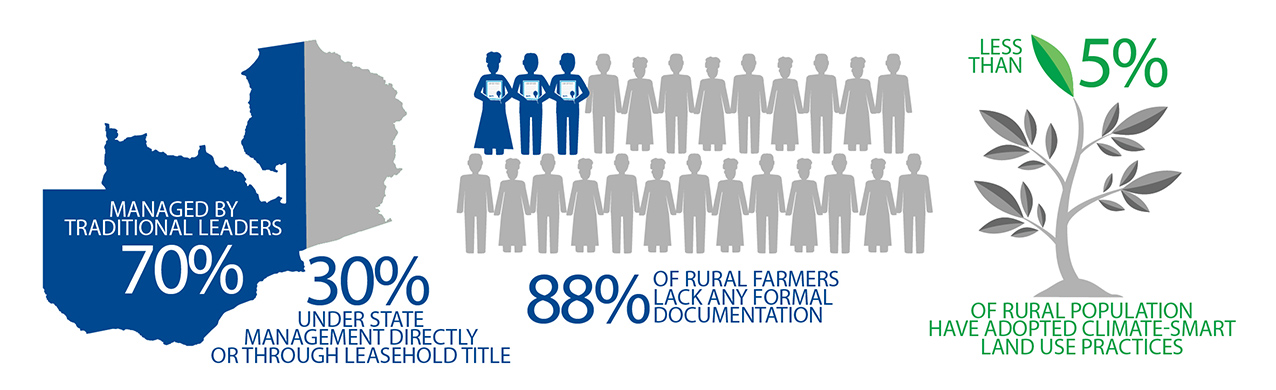

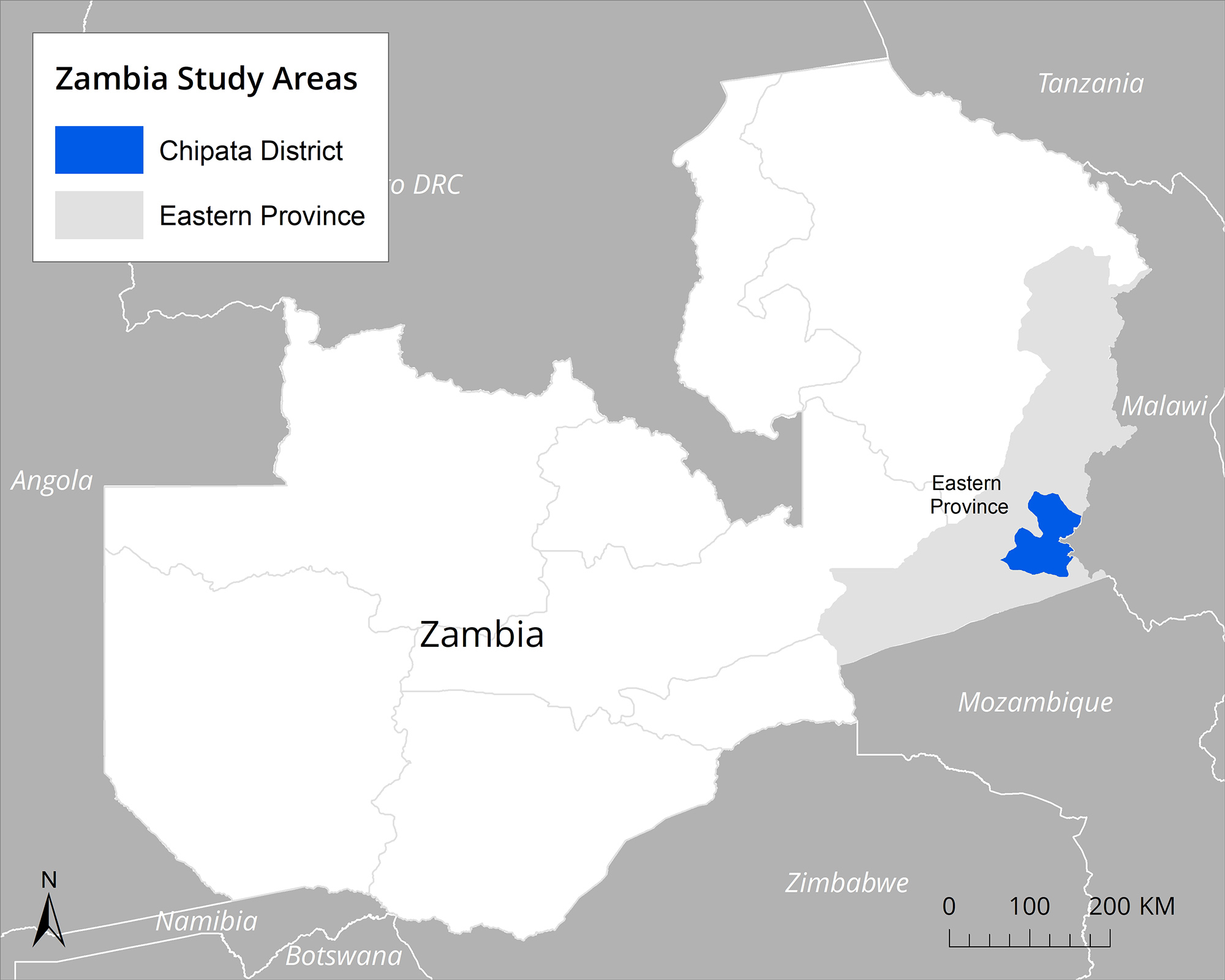

Dr. Matt Sommerville is the chief of party of the USAID Tenure and Global Climate Change (TGCC) program, which has implemented research and pilot activities to improve sustainable land management through strengthening land and resource rights. The program was active in Zambia, Burma, Vietnam, Ghana and Paraguay. From 2014 to 2017, Sommerville was based in Zambia, backstopping a customary land certification process that resulted in the documentation of over 15,000 parcels of land across five chiefdoms in Zambia’s Eastern Province.

Dr. Matt Sommerville is the chief of party of the USAID Tenure and Global Climate Change (TGCC) program, which has implemented research and pilot activities to improve sustainable land management through strengthening land and resource rights. The program was active in Zambia, Burma, Vietnam, Ghana and Paraguay. From 2014 to 2017, Sommerville was based in Zambia, backstopping a customary land certification process that resulted in the documentation of over 15,000 parcels of land across five chiefdoms in Zambia’s Eastern Province.

Yaw Adarkwah Antwi has more than 20 years of experience in land tenure and administration policies and holds a Ph.D. in Sub-Saharan Africa Urban Land Markets and an M.A. in Property Valuation and Law. Antwi has helped to develop land policies, particularly on the topics of land tenure, land management and agricultural development, in Liberia, Ghana, Nigeria, Sierra Leone and, within the COMESA region, Kenya and Sudan. Antwi is currently the country lead and senior land tenure expert on the Improving Tenure Security to Support Sustainable Cocoa project funded jointly by USAID and Hershey’s.

Yaw Adarkwah Antwi has more than 20 years of experience in land tenure and administration policies and holds a Ph.D. in Sub-Saharan Africa Urban Land Markets and an M.A. in Property Valuation and Law. Antwi has helped to develop land policies, particularly on the topics of land tenure, land management and agricultural development, in Liberia, Ghana, Nigeria, Sierra Leone and, within the COMESA region, Kenya and Sudan. Antwi is currently the country lead and senior land tenure expert on the Improving Tenure Security to Support Sustainable Cocoa project funded jointly by USAID and Hershey’s.