USAID’s Land Technology Solutions Project (LTS) has recently completed a comprehensive update to Mobile Applications to Secure Tenure (MAST) which uses innovative technology, including GPS enabled phones and tablets, to efficiently and effectively document land rights. Countries, communities and companies interested in meeting their commitments to establish deforestation-free value chains, boost agricultural productivity, quickly inventory land and document holdings or clarify and document land uses can now harness a much-improved suite of tools to expedite their work.

LTS now provides a suite of integrated support services to USAID Missions to promote and scale the use of MAST worldwide. LTS services focus on meeting the needs and interests of USAID Missions and their implementing partners to achieve host country strategic development objectives, including those outlined in the Global Food Security Strategy, the USAID Gender Equality and Women’s Empowerment Policy, and the USAID Biodiversity Policy. The tool is yet another example of how USAID works as a catalyst to help others, including civil society, corporate partners and other governments, expedite their efforts to achieve development goals and create a durable path out of poverty.

What is MAST?

USAID’s MAST is a suite of innovative technology tools paired with inclusive training and approaches that use mobile phones and tablets to efficiently, transparently and affordably map and document land and resource rights. MAST can help people and communities define, record and register local land boundaries and important information, such as the names and photographs of people who use the land and information about how they use it. MAST combines an easy-to-use mobile phone application with a participatory approach that empowers citizens in the process of understanding, mapping and registering their own rights and resources.

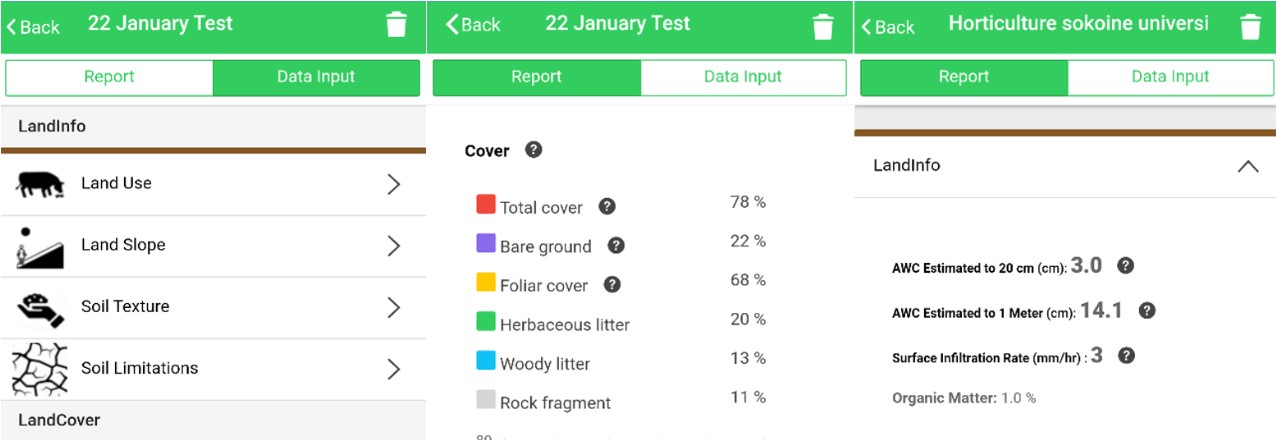

The MAST application provides a suite of tools to support the collection and management of land rights information, including a mobile application to capture land rights information in the field and a back-end land rights data management application with tools to manage an inventory of land information. MAST Mobile is an Android mobile application.

Since 2014, MAST has been used by stakeholders in Tanzania, Zambia and Burkina Faso, to clarify and document claims to land. In these countries, MAST has provided transparent and effective mechanisms to improve land governance, build institutional capacities, engage citizens and help them understand their rights and responsibilities.

Enhanced Technology

Over the last eight months, LTS has refined and improved MAST technologies and approaches. LTS has updated key components of the MAST software application framework and upgraded the MAST data model from Social Tenure Domain Model (STDM) to more common standard Land Administration Domain Model (LADM). With an updated Data Model, MAST is now more compatible with models used in larger, more formal land administration or registration systems.

Enhanced Land Record Management

A more robust land registration module has been integrated into MAST based on feedback and lessons learned in Tanzania and Burkina Faso. In these countries, users identified the need for a land registration module. This has been integrated and configured to manage a series of prototypical subsequent land registration transactions such as transfers, sales, leases and mortgages. The modular nature of its integration into MAST provides enhanced functionality, and an important base for country-specific customization, but doesn’t reduce its flexibility and responsiveness for community mapping.

Improving Efficiencies and Eliminating Errors

To improve data capture of individual land holdings, a tasking and data collection manager has been implemented in MAST. The tasking manager does away with the need to manually assign work areas to surveyors and uses integrated geospatial tools. Integrated tools allow users to define and assign work allocation units to surveyors to increase efficiencies and avoid capture of redundant data. To further address issues associated with online data management and mapping tools on slow and unstable internet connections, a QGIS plugin has been modified to be used with MAST. Integrating QGIS tools allows administrators the ability to download geospatial data, utilize QGIS to edit data in offline mode and to sync data back to the main MAST database. Such editing functions have been augmented by the integration of topology tools that can be used to flag and check errors.

Extending Tools for Resource Management

The MAST mobile application has also been updated. The parcel mapping tool has been extended to incorporate tool sets derived from USAID’s Land Tenure Assistance program in Tanzania, which extended MAST to include more robust data editing functions and to document new, existing and/or disputed claims to land. MAST mobile has also been linked via Bluetooth connection to several consumer-grade GPS tools to improve accuracy of mapping available on native mobile devices. Most importantly, MAST Mobile has recently been extended to include a resource mapping module. The resource mapping module uses a hybrid land classification system to collect resource information such as point of interest, road networks, forest areas or water bodies to enrich the base data in MAST and the availability of data to communities.

Continued Deployments, Continued Refinements

These improvements to MAST will enable users to capture and process land and resource rights more efficiently, although MAST still requires technical knowledge and advanced skills to set up and configure.

As the suite of tools is used in other geographies and for new purposes, LTS will incorporate new features and/or improve existing ones. And as an open source project, MAST will be continually improved upon and updated. LTS will maintain a core MAST platform and incorporate the best of these improvements.

LTS will continue to work across organizational boundaries to make MAST a truly global tool, and an empowering experience, to address land tenure insecurity.

In Liberia, the community organizers for USAID’s

In Liberia, the community organizers for USAID’s  Women’s participation in land governance is low, and in certain cases absent, in both statutory and customary governance systems. Women are disadvantaged in both statutory and customary land governance systems due to underrepresentation, customary norms requiring male accompaniment, lack of consultation and information, low recognition of women’s legal rights to land and inheritance, and the dual system of land governance, both of which contain biases against women.

Women’s participation in land governance is low, and in certain cases absent, in both statutory and customary governance systems. Women are disadvantaged in both statutory and customary land governance systems due to underrepresentation, customary norms requiring male accompaniment, lack of consultation and information, low recognition of women’s legal rights to land and inheritance, and the dual system of land governance, both of which contain biases against women.

Tajikistan’s arable land is limited, covering just seven percent of its territory. Without a land market, land cannot easily be transferred from less to more efficient types of use, hindering efforts to alleviate the country’s significant rural poverty and food security challenges. Tajikistan’s robust agricultural sector accounts for 57 percent of employment and nearly a quarter of the national GDP. The emergence of a land market is critical to spurring equitable economic growth, and empowering entrepreneurial farmers to either expand their land holdings or lease them.

Tajikistan’s arable land is limited, covering just seven percent of its territory. Without a land market, land cannot easily be transferred from less to more efficient types of use, hindering efforts to alleviate the country’s significant rural poverty and food security challenges. Tajikistan’s robust agricultural sector accounts for 57 percent of employment and nearly a quarter of the national GDP. The emergence of a land market is critical to spurring equitable economic growth, and empowering entrepreneurial farmers to either expand their land holdings or lease them.