Executive Summary

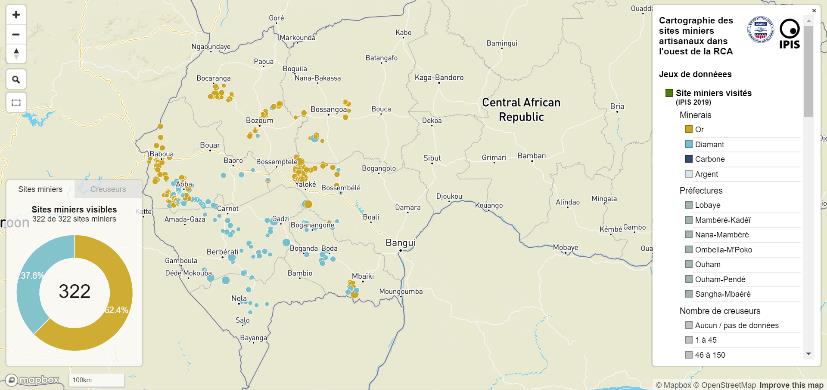

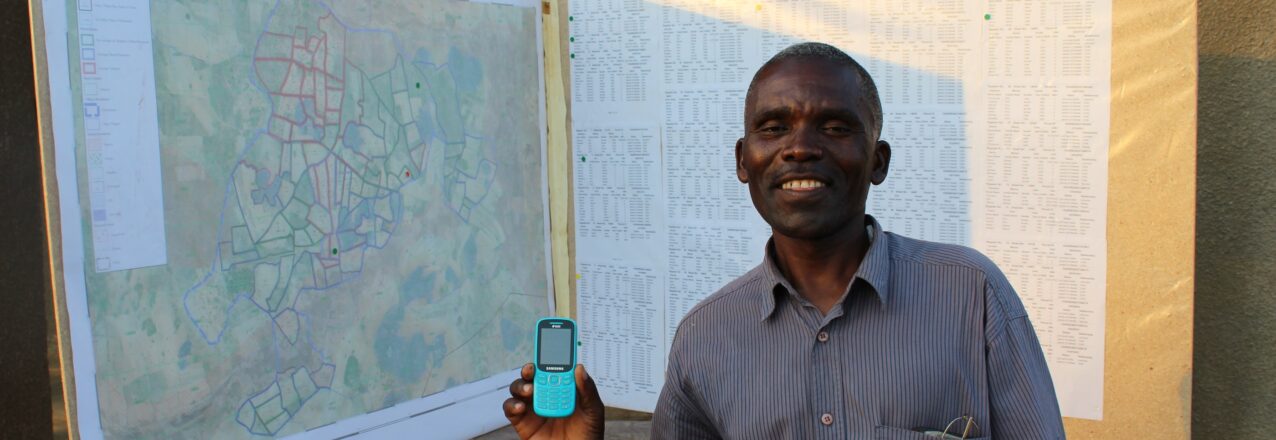

The Artisanal Mining and Property Rights (AMPR) project in the Central African Republic (CAR) supports the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) Land and Resource Governance Division in improving land and resource governance and strengthening property rights for all members of society, especially women. It serves as USAID’s vehicle for addressing complex land and resource issues around artisanal and small-scale mining (ASM) in a multidisciplinary fashion. The project focuses primarily on diamond and, to a lesser extent, gold production in CAR, as well as targeted technical assistance to other USAID Missions and Operating Units in addressing land and resource governance issues within the ASM sector.

Ever since the early days of the Property Rights and Artisanal Diamond Development (PRADD I and II) projects, the issue of the role of various forms of livestock production in diamond mining areas of CAR has surfaced in the project sites in the southwest regions of the country. While participatory rural research carried out over the years has often highlighted the complex interactions between artisanal mining and livestock production, no in-depth analysis has examined the nuanced relationship that different groups of herders have with armed groups, artisanal diamond mining, and farming communities. This report is based primarily on survey instruments and summaries of quantitative data, supplemented by qualitative analysis through focus groups and semi-structured interviews, to assess the nature of the interactions among these three livelihood groups and whether the relations are symbiotic, hostile, or predatory.

The research agenda explored the mechanisms that exist locally to provide security and to manage conflict, and from this foundation, identified locally owned and realistic recommendations these livelihoods groups themselves proposed to promote peaceful collaboration with desired mutual benefits for all. For this reason, this summary of field results presents the voices of those often not heard, including women and nomadic pastoralists. It does so without making value judgments on the merit of their opinions, but to ensure they are considered in decision-making that affects their communities. The format for this report is somewhat different from more classical presentations. Evocative and direct quotes from respondents are peppered throughout this report as a way for the respondents themselves to narrate realities. Results from the analysis of data from questionnaires complement the quotations from local actors.

Definitional questions abound when referring to those raising livestock in the southwest. Ethnic groups known by the labels of Fulani, Peulh, FulBe, and Mbororo raise cattle and small ruminants and traverse the territory. It is often difficult to distinguish among labels used for herders such as “semi-settled,” “semi-nomadic,” “transhumant,” and “foreign transhumants.” This report uses the term “semi-settled” and not “semi-nomadic.” The defining feature of this latter group of semi-settled livestock raisers is not their movement, but that the majority of the people (including most of the elderly, the women, and the children) have chosen to settle in one place. The settlement pattern matters for reasons of nationality, the sense of belonging to a place, and access to education and other public services, as limited as they might be in CAR. That said, populations of long-distance herders, referred here as “transhumant pastoralists,” herd their livestock across national borders and often along seasonal tracks, or corridors, in search of pastures and water.

Case study sites were selected from across six sub-prefectures in the southwest prefectures of Sangha-Mbaéré and Mambéré-Kadéï. The sub-prefectures of Nola, Carnot, and Berberati are Kimberley Process Certification Scheme (KPCS) compliant; Bayanga, Sosso-Nakombo, and Gamboula are not KPCS compliant, so diamonds extracted and sold from these places are viewed as conflict diamonds. The team conducted field research during the dry season from January through February 2020. The field research team consulted with 834 people through high-level workshops, focus groups, and individual interviews. The research team spent much time in many rural communities, traveling by motorcycle where possible to villages and herder camps. The team often slept in the village or herder encampments as a way to gain trust and confidence from the respondents.

Southwestern CAR is crisscrossed by many commercial trade routes that support both farming and livestock production but also trading linkages with national and international markets. Sub-soil resources also consist of rich deposits of diamonds and gold, often located in and along the many rivers and streams of this tropical landscape. Historically, various types of symbiotic relationships have brought mutual benefits and social goods to farmers, herders, and miners through inter-community trade and mutually beneficial social interactions.

The southwest has long been characterized by instability as expressed through significant banditry and intercommunal violence. Armed groups have variously sought to provide security, protect their kin, or prey on the population. Ever since the 2012/2013 takeover of the country by the Seleka forces, local self-protection groups, called now the anti-Balaka armed groups, emerged in the southwest to respond to the predations and violence associated with the Seleka coalition. Over the years, other armed groups, called Siriri and 3R (Return, Reclamation, Rehabilitation) came into existence, ostensibly to defend herders from aggression from anti-Balaka. While this report does not go into these complex shifting alliances, suffice to note that complex webs of social and economic grievances characterize relations on all sides. The attached bibliography provides background literature on this subject.

There is clear evidence that, whether or not they supported 3R in the past, most herders are now preyed upon by 3R and do their best to avoid them. This includes semi-settled herders in CAR and foreign transhumants from Cameroon and Chad. At the same time, a small minority of herders are more supportive of and openly reliant upon 3R; it is important for researchers to understand why that is.

During the 2012–2015 crisis, the semi-settled herders long living in CAR and those undertaking traditional cycles of seasonal transhumance between the north and the south of the country were displaced, but now are gradually returning. This presents many challenges, such as competition over pasture zones that were abandoned during the crisis, but up until the 1960s territories had been reserved by national law and administrative fiat for pastoralists. The field research carried out for this study concludes that the root cause of many contemporary conflicts in the southwest is the growing occupation of these pasture zones by those now using the land for farming, diamond and gold mining, and settlements. To compound this growing competition over resources, “new” transhumants—herders from other parts of the country, Chad, and Cameroon—are also keen to graze their livestock in these rich pastures and associated plentiful sources of water for livestock.

The findings from this field research suggest that a nuanced approach to conflict management in southwestern CAR is needed to respond to these complex social dynamics, themselves rooted in the environmental setting of rich pasturelands and plentiful water. Unfortunately, the southwest is characterized by many polarized reactions to perceived injustice and this has led to a wildly swinging pendulum of retribution by many parties to deep-seated conflicts. While there is much scope to kindle or renew mutually beneficial collaboration built on generations of interdependence, solutions must be locally owned. Outsiders, including government and donor agencies alike, must accept these realities in all their complexity.

The field research showed that at least 50 percent of the herder respondents report having been attacked by 3R, 15 percent by anti-Balaka groups, and 5 percent by unnamed armed groups in the 12 months prior to the research. At least 50 percent have been victims of cattle rustling and at least 25 percent have been taxed illegally by either an armed group or the authorities. The costs of these predations are high. As the local authorities in Carnot said, “When 3R arrive in the village, they tell communities, ‘Don’t be scared, we won’t hurt you; we’ve only come for the herders.’” The majority of herders are caught in the middle of a difficult situation; they are preyed upon by 3R armed groups while also facing suspicions from artisanal miners and sedentary agricultural communities for being in collusion with the 3R.

The forms of predation are many, but the 3R requires herders to pay for protection against cattle theft. A herder with 100 head of cattle may have to pay as much as 150,000 XAF ($260) and/or one or two cattle every couple of months to the 3R. Livestock raisers claim this is extortion and they try to vary their routes to try to avoid this payment to the 3R wherever possible, often at great personal cost. Yet when attacks from anti-Balaka and others occur on the herders, livestock raisers inform the 3R.

Most herders are not involved in the diamond trade and have no personal or commercial engagement with miners beyond limited sale of milk and meat. That includes most foreign transhumant pastoralists from both Cameroon and Chad. That said, a small minority of herders seem to be involved in the diamond trade. This includes some owners of large herds, who commission people to extract or procure diamonds for sale to traders in Cameroon.

When livestock raisers are asked about the root causes of insecurity, more than 50 percent of all respondents cite the presence of armed groups as a factor; over 60 percent cite weak state presence, poverty, and porous borders as factors. Respondents suggest that the presence and status of armed groups is a symptom of these three factors, but not the principal cause. As a result of this perception of insecurity, several respondents called on an armed group if they deemed it necessary for their security, as they do not believe the state security forces can protect them. The field surveys indicated that 6 percent of farmers and 19 percent of artisanal miners admit reliance on anti-Balaka self-defense groups for security, and 5 percent of herders admit to relying on 3R for protection from anti-Balaka groups and other groups involved in banditry.

The 3R is a signatory to the Khartoum peace process and it portrays itself as the defender and protector of herders. The organization has sought to impose itself as the broker of disputes between farmers and herders, especially around the contentious issues of crops damaged by livestock and stolen cattle. The 3R has broken away from the Khartoum process, its leadership is fragmenting, and it remains a potent military threat to the Mission de Nations Unies pour la Stabilisation en Centrafrique (United Nations Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in the Central African Republic [MINUSCA], the UN peacekeeping force) and the Forces Armées Centrafricaines (Central African Army [FACA]).

The 3R is not the only armed group situated in the southwest, nor are they the only ones preying on herders, artisanal miners, and farmers. Since the narratives surrounding each of these armed groups are so polarized and complex, it is best to step back and look at the situation more broadly. It seems that armed groups will seek to fill any vacuum created by an absence of trusted and competent state services and security forces. The field research suggests that rural communities facing predation from whatever source will search out protection from an armed group in situations where the state is unavailable or predatory; where mechanisms of conflict mediation and resolution are non-existent or biased; and where banditry, livestock theft, and other forms of extortion are rampant. Notwithstanding—or perhaps because of—all of these realities, a small minority of herders are more supportive of and openly reliant upon 3R, whether for protection or as part of criminal enterprises, including illegal diamond smuggling into Cameroon. While rumors abound that livestock herders are involved in extensive diamond smuggling, this does not appear to be widespread. Among the 800 people consulted during the field research, only three respondents admitted first-hand knowledge of herders engaging in the diamond trade with Cameroon. While there is evidence of what is likely diamond smuggling, there is no evidence that this occurs widely

Interventions which focus exclusively on armed groups and diamond smuggling give too much airtime to a mostly male criminal minority and fail to address the needs of women and others who are seeking to make their livelihood without recourse to violence.

Information gathering around an illegal activity like diamond smuggling is fraught with difficulties. While many artisanal diamond miners admit to selling diamonds for export to Cameroon, these same respondents note that this illegal diamond trade damages relations with their collector patrons. The study could not go into depth around this question, a complex set of issues addressed much more thoroughly by other studies carried out by the USAID AMPR project. That said, while it is clear that herders have capital that could be used to finance diamond trading, capital appears to be most frequently invested in reconstituting the livestock herds. Herders are trying to rebuild their herds that were severely diminished by predation in recent years. The price of livestock sold for meat in rural markets is very high, an indication of the scarcity of livestock. The reconstruction of herds is most likely a much higher priority for livestock raisers than entering into risky transactions around diamonds. That said, it appears that a minority of seasonal transhumance pastoralists may be financing what is probably the illegal mining and trade in diamonds.

There is currently very little social integration between settled communities and semi-settled herders, and even less with transhumant herders. Well managed and peaceful transhumance needs to yield very visible benefits for all communities.

Focusing excessively on the role of livestock raisers in the diamond trade feeds into the victim-narratives that fueled the 2012–2015 crisis, which fomented a coup and caused the flight of people, cattle, and capital from the region. The priority should be placed on recognizing the role that livestock herding brings to the rural and regional economies that, if taxed fairly and properly, would help generate the state revenue needed to provide state services and security. Another vital issue is to focus on the plight of female herders, who suffer from minimal access to health care and other services. The decapitalization of the livestock herds in the southwest due to the years of predation is demonstrated by the field research data that showed that less than half of the farmers in the areas studied raise livestock and very few keep cattle. In effect, the field research suggests that terms of trade between farmers and livestock raisers are generally not equal. Farmers are more dependent on the sale of goods to herders than the purchase of goods from them. This indicates that capital flows from herders to farmers through unequal terms of exchange, but with cross-border transhumance pastoralism providing capital flow into CAR from neighboring countries.

The field research team concludes from the rich field observations that diversification of livelihoods and access to markets is critically important for the promotion of household resilience to economic shocks. Currently, many opportunities are being missed to strengthen trading relations between livestock herders and artisanal miners. From the perspective of peacebuilding in the conflict-ridden southwest, creating greater interdependence between different livelihood systems (a hallmark of the past symbiotic relations) would generate many peace dividends.

Recommendations to Promote Peaceful Relations for Mutual Economic Benefit

As is expected from any intense field research period, several recommendations for policy and action emerged throughout the extensive discussions and interviews with the respondents. These recommendations represent the points of view of the respondents and are touched upon in greater detail in the body of this report. These are summarized and categorized below.

Recommendations Addressed to the CAR National Government: Provide clear guidance on local dispute resolution processes, including: an agreed tariff of damages awardable; a schedule of fees chargeable for arbitrating disputes; guidance on who are the appropriate authorities responsible for dealing with different criminal and civil grievances; and a whistleblowing mechanism to report corruption and other abuses of power.

Clear guidance is needed on the processes for registration of transhumant pastoralist herders, including the filing of route plans and appointment of a named person to inform the local and traditional authorities along that route, and the negotiation of arrangements for the arrival of herders. The government should put in place a clear and transparent system of taxation of herders, both semi-settled and transhumant, that specifies benefit distribution at the municipal, local, and village levels. The authorities could play a key role in setting up a collaborative decision-making body to determine the future status of the designated pasture zones, issuing bold and clear decisions about the status of structures that block the cattle corridors.

Recommendations Addressed to Local and Traditional Authorities: Engage in the swift resolution of outstanding cases of restitution of homes of livestock raisers occupied by others. Improve collaborative and community engagement in the management of the Dzanga-Sangha National Park, including compensation for farmers whose crops are destroyed by wild animals.

Recommendations Addressed to the Security services of FACA, MINUSCA, and the Gendarmes: Mount patrols along agreed migration routes, particularly at known flashpoints and border crossings, and to protect technical services.

Recommendations Addressed to the Fédération Nationale des Eleveurs (National Federation of Livestock Producers [FNEC]) and Government Technical Services: Put in place formalized dialogues between livestock herders and others to negotiate access to pastures and livestock migration corridors. Ensure low-cost access to technical services, including veterinary services, along livestock migration corridors and particularly at border crossings. Promote security-marking of cattle, whether by branding or by Radio Frequency Identification (RFID) chips to establish ownership. Require abattoirs to verify ownership of livestock before purchase.

Recommendations Addressed to International Organizations: Promote training in mediation and arbitration techniques for traditional and local authorities, women, and young people. Provide training and support for livelihood diversification, including fisheries and veterinary services, while improving producer access to markets.

The ASM gold market analysis, with a specific focus on the DRC, shall provide information on the current market actors’ interests and the structural and perceived challenges and drivers of trading and/or investing in ASM gold, and specifically ASM gold originating from eastern DRC. As well as reviewing the demand for ASM gold, this report includes a broader analysis of the ASM gold supply chain to define the broader market system and define motivations and barriers at the different stages of gold extraction, trade, sourcing and investment. The key objectives of the market analysis are summarized below.

The ASM gold market analysis, with a specific focus on the DRC, shall provide information on the current market actors’ interests and the structural and perceived challenges and drivers of trading and/or investing in ASM gold, and specifically ASM gold originating from eastern DRC. As well as reviewing the demand for ASM gold, this report includes a broader analysis of the ASM gold supply chain to define the broader market system and define motivations and barriers at the different stages of gold extraction, trade, sourcing and investment. The key objectives of the market analysis are summarized below.

The USAID Artisanal Mining and Property Rights (AMPR) Year II workplan stipulated that under Objective II: Strengthen Community Resilience, Social Cohesion, and Response to Violent Conflict in the Central African Republic (CAR) and under Intermediate Result 2.1: Support Inclusive Community Dialogue Especially between Different Religious and Ethnic Groups to Resolve Conflict Over Land and Natural Resources In Compliant Zones the following deliverable: “Develop a roadmap that identifies key research questions and next steps for policymakers, academics, and practitioners to advance understanding and respond to conflicts (Contract Activity 2.1.3).”

The USAID Artisanal Mining and Property Rights (AMPR) Year II workplan stipulated that under Objective II: Strengthen Community Resilience, Social Cohesion, and Response to Violent Conflict in the Central African Republic (CAR) and under Intermediate Result 2.1: Support Inclusive Community Dialogue Especially between Different Religious and Ethnic Groups to Resolve Conflict Over Land and Natural Resources In Compliant Zones the following deliverable: “Develop a roadmap that identifies key research questions and next steps for policymakers, academics, and practitioners to advance understanding and respond to conflicts (Contract Activity 2.1.3).”