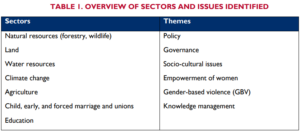

This report presents findings from a political economy analysis (PEA) of women’s land access in Western and Northern Côte d’Ivoire. The PEA aimed at providing answers to the following overarching question: “Why do women in Côte d’Ivoire continue to experience inequitable access to land despite laws and policies that protect their land rights?” The objective was to go beyond typical explanations like “socio-cultural barriers” or the “lack of awareness of the law by rural populations.” Instead, the study sought to explore the underlying factors behind this inequality by emphasizing structural constraints, interests and motivations of actors, and current dynamics.

Foundational Factors

Several foundational factors were explored in the study. First, with respect to national laws and the institutional framework, the study did not identify any explicit barriers preventing women from owning land and benefitting from equal inheritance rights. On the contrary, recent reforms strengthen women’s land rights, including the 2016 Constitution, the reforms to marriage and inheritance laws, as well as institutional reform such as the creation of the National Observatory for Equity and Gender (ONEG) and the Rural Land Agency (AFOR). However, it is important to note that the process of obtaining formal legal rights to rural land creates obstacles for women because the legal framework enshrines customary law as the source of modern property rights. For example, even if a woman has the right to apply for an individual land certificate, the Village Land Management Committee (CVGFR) controlled by men will likely reject her request based on customary rules about women’s property rights. The system therefore risks reinforcing the discrimination against women prevalent in the customary land management system.

Indeed, the socio-cultural foundations of these customary traditions differ fundamentally from statutory rights in their underlying logic. Customary rules are premised on the paternalistic notion of “taking care” of women that places them as a social inferior under the tutelage of a man. As such she is not in an equal relationship with men, as the man (husband, father, brother) must provide for the woman but ultimately retains control over her. Indeed, all economic and social life revolves around a gender-based division of roles, and land is considered a collective family asset controlled by men. Admittedly, women play a decisive role in determining inheritance rights depending in matrilineal inheritance systems, but these systems remain patriarchal because men still control the land.

This logic is in direct opposition to the spirit and letter of the law, creating a disconnect between the customary systems that dominate in practice and the statutory systems where women have equal rights. It is important to note, however, that the customary systems are not static and are evolving, especially in response to broad-based economic forces. Specifically, the rise of cash crop agriculture— coffee-cocoa-rubber in the West and cotton-cashew-mango in the North—have strongly impacted land management practices. First, these crops have accelerated a process of commodification and individualization of land by increasing its economic value. The value has only risen as demand for these crops have fostered land pressure as remaining open space is occupied by locals and migrants for agriculture. This land pressure in turn has contributed to land speculation, land grabbing and land conflicts. While these developments have had negative impacts on women’s land access, they have also created new opportunities and have led to changes in customary practices. For example, in the North the study documented a weakening of matrilineal (uncle to nephew) inheritance systems due to children demanding to inherit high-value plantations from their parents, and in the West more and more women are using the legal system to claim inheritance rights as the customary system is unable to provide for them. This contested and dynamic environment can afford new opportunities for women provided that the risks around conflict and power plays are managed.

Land tenure dynamics

The study identified a variety of actors involved in land management, especially with respect to land conflicts, and noted that these actors sometimes compete with each other. For example, the study found that in some cases courts are in conflict with sous-préfets or land administration officials on whether to certify disputed land, and there are also conflicts with new institutions like the Council of

Traditional Chiefs and Kings (CRCT). These tensions undermine the legitimacy and efficacy of these institutions which are supposed to create and enforce clear and predictable rules. In the West, but also increasingly in the North, one observes a lack of trust and a perception that these institutions are biased. As a result, land users rely less on institutional processes and more on networks of influential or powerful people who can advance individual interests. In such a context, the ecosystem of actors is characterized by “might makes right” where might is determined by economic and political power.

Women are particularly vulnerable in such a system because they tend to be at a disadvantage in male- dominated power politics because they have less money, less political power and fewer friends in high places to advance their interests. In such a context, advancing the cause of women’s land rights requires advocacy with those who do have power and influence, including women powerbrokers, so that women’s interests stand a better chance of being considered.

It is also necessary to strengthen women’s capacity to succeed in this contested ecosystem through developing networks and especially supporting the most vulnerable women (widows, young girls, and the poor). Strengthening women’s economic power so that they are on an equal footing with men is also key. Supporting women-led advocacy networks can leverage social capital through collective action and better access to information. This approach can ultimately contribute to the deconstruction of negative social representations around women. However, it will require working on the system as a whole with actions aimed at reducing gender inequality.

Engagement opportunities

The study was carried out with the aim of collecting data from the field in order to inform the project’s activities. Based on the study’s results, the following programmatic opportunities were identified.

Social dialogue

An important tool for social and behavioral change, social dialogue is relevant in several respects. First, in the context of a “do no harm” approach, dialogue makes it possible to mitigate risks of certain actors perceiving change as threatening. In addition, communities appreciated the participatory methods used during the study and expressed the desire for more discussion around land. Social dialogue creates spaces for communities to identify underlying causes and solutions to their problems on their own. It also allows for the full participation of different profiles of women (local and migrant for example) while building greater gender-awareness with men.

Social behavior change communication

In addition to social dialogue, strategic messages can be developed and delivered articulated around existing social values and norms identified during the study. Social dialogue will help them become more open to these messages of change. To the extent possible, these messages should be conveyed by community members, including women and men who can serve as role models and positive examples.

Awareness-raising and legal education

Local communities need to be better informed about the 2019 reforms to marriage and inheritance laws, the 2016 Constitution and the 1998 rural land law, and other similar legislation. These awareness- raising and legal education actions can also be integrated into social dialogue exercises which will help create spaces to discuss the gaps between the laws and actual practice, as well as spur discussion on how to bridge those gaps.

Transformative approach to gender

The study demonstrates how individual and collective beliefs around women’s social position are key barriers, and that gender norms need transformation. Tools and approaches that get at the heart of these beliefs will help create the basis of their transformation. To do this the project will need to target reference groups that influence these social norms.

Conflict resolution

The study highlighted the complex conflict management environment in which the project will navigate. Actions should be sensitive to these dynamics and tailored to individual contexts. In particular, the project should consider working with existing conflict management actors rather than introducing new ones. Gender-sensitivity training and mentorship, for example, can help reduce bias and discrimination in these customary and government institutions.

Strengthening and formalizing land rights

The study analyzed the diverse needs of women with respect to land rights. Some require assistance in inheritance disputes, others require land certification and others simply more voice in male- dominated collective decision-making. Legal and technical support tailored to these different needs can help women and men exercise these rights peacefully and sustainably. To achieve this the activities and instruments need to be tailored to each community’s and individual’s circumstances.