Overview

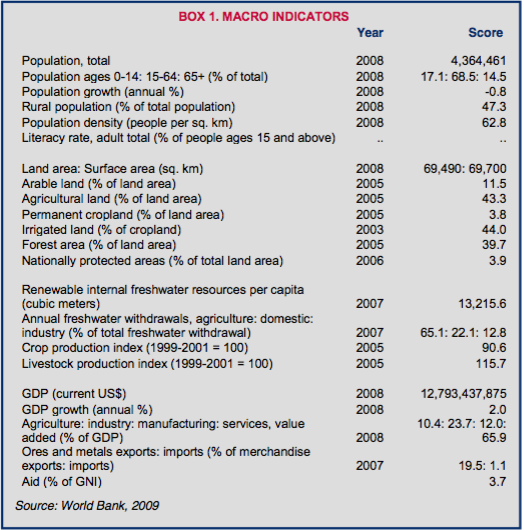

Over the last 20 years, the Republic Georgia has privatized ownership of both rural and urban land, drawing upon significant amounts of technical assistance from donors, including USAID, to do so. Initial transfers of farmland from 1300 collective and state farms in 1992 enabled households to acquire up to 1.25 hectares of land to produce food for their own consumption. Nearly half of Georgia’s 4.3 million people now live in rural areas and have ownership of some land, although not all rural households are full-time farming households. In 2007, the average family farm size was only 0.7 hectares.

Not all agricultural land has been privatized, however. In the late 1990’s, the state chose to retain ownership of more than half of all agricultural land (some 2 million hectares) and to use leasing arrangements to allocate operating rights to larger, commercially oriented enterprises. This strategy did not prove successful. Agriculture declined as a share of GDP, many rural households lived well below the poverty line, and the larger farms operating on lands leased from the state were not as efficient or productive as envisioned. Short lease-terms for state-owned land, for example, provided little incentive for investment or sustainable management. In 2005, the Government of Georgia (GOG) began privatizing the agricultural land remaining in state ownership. The existing lease arrangements had not provided farmers and other investors the tenure security needed to encourage serious investments in agriculture. As a result, the GOG stopped the practice of farmland leasing, mades lands already held under leasehold available for privatization, and granted leaseholders preemption rights. The aims of this large-scale privatization strategy were to complete the land privatization process, create incentives for the establishment of large-scale farms and increase productivity.

Some observers note that poor environmental management, in general, is the result of inadequate property rights and tenure security. A new realignment of rural property rights may be needed to realize greater agricultural productivity and income growth.

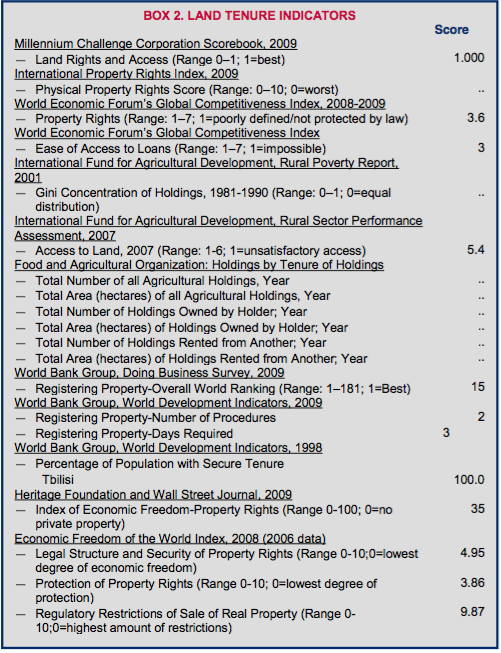

Privatization of non-agricultural land has been less problematic. It is more readily registered, marketed, and transferred. Urban property reforms were undertaken in 1997, five years after rural land privatization was initiated. Georgia’s procedures for registering property – largely for urban-based industries – are now significantly simpler and less expensive than those of other countries in Eastern Europe and Central Asia.

Disputes over property rights mark the Government of Georgia’s relationships with the territories of South Ossetia and Abkhazia. These are rooted in longstanding differences and will be resolved only through political negotiation at a higher level. However, as a number of people have been internally displaced by conflicts, property-rights issues are likely to remain on the agenda for some years to come.

Key Issues and Intervention Constraints

While agriculture contributes relatively little to Georgia’s GDP, more than half the population continues to live in rural areas, often under conditions of extreme poverty. The small size of landholdings may constrain some households’ abilities to increase productivity. Procedures for leasing state land do not result in expected levels of marketed production. Donors could work with the Government of Georgia to develop another wave of rural land reform, including, for example: testing new approaches to leasing; privatizing land still held by the state; and complementing these reforms with additional investments to make the new owners more competitive agricultural producers. Donors should also continue to provide technical support to government institutions responsible for survey and title registration to ensure that reforms are administered fairly and rapidly.

A large number of laws, orders, and decrees now apply to Georgia’s land sector, so it is difficult to research law applicable to a particular issue. This reduces transparency and may inhibit the design and implementation of needed changes. In addition to supporting government efforts in this regard, donors should continue to promote the work of nongovernmental organizations that help to ensure the public’s awareness of its rights and responsibilities as well – for example, the work of the Association for the Protection of Landowners’ Rights. Specifically, donors should support analyses of Georgian law governing women’s land rights, including family law, and assess the degree to which Georgian women have participated in and benefited from land privatization, with particular attention to women-headed households. Based on the analysis and findings of that assessment, a follow-on action agenda might be considered for support.

Summary

The Republic of Georgia, a former Soviet republic, is a largely mountainous, low-income, food deficient country in which 24% of the population lives in poverty while a further 9% lives in extreme poverty. Poverty is concentrated in rural areas where 47% of the population resides. Rural areas have not benefited from nationwide economic growth.

Historically, agriculture has been one of Georgia’s most important sectors, due to the country’s diverse climate and relatively good soils. Following the dissolution of the Soviet Union, however, Georgia’s agricultural output declined dramatically due to the severance of trade ties with other former Soviet republics, as well as war and ethnic conflict. As a result, Georgia became a net importer of agricultural products.

In 1992, the government began to privatize rural land. In the lowlands, the government allocated 1.25 hectares to each rural family from the holdings of the collective and state farms that had dominated production in Soviet days. In the highlands, the government allocated five hectares to eligible families. The new government of Georgia retained more than half of all agricultural land in state ownership with the intention of leasing it out for commercial agricultural purposes. By 2002, these programs had created a class of private rural land owners on 0.7 million hectares of agricultural land. However, leaseholders controlled 0.3 million hectares of state-owned lands, and another million hectares of state-owned land was not cultivated due to problems of poor soil, location of the land, and damaged irrigation and drainage systems.

In 1992, the government began to privatize rural land. In the lowlands, the government allocated 1.25 hectares to each rural family from the holdings of the collective and state farms that had dominated production in Soviet days. In the highlands, the government allocated five hectares to eligible families. The new government of Georgia retained more than half of all agricultural land in state ownership with the intention of leasing it out for commercial agricultural purposes. By 2002, these programs had created a class of private rural land owners on 0.7 million hectares of agricultural land. However, leaseholders controlled 0.3 million hectares of state-owned lands, and another million hectares of state-owned land was not cultivated due to problems of poor soil, location of the land, and damaged irrigation and drainage systems.

While 54% percent of employed Georgians work in the agricultural sector, in 2008 that sector generated only 10% of the country’s GDP of US $12.7 billion.

Despite laws protecting women’s access and rights to land, women in Georgia often lack information about their rights and, as a result, tradition, customary law and religious law shape attitudes and behavior. Women have little involvement in economic decision-making within the family and do not have the same rights and responsibilities as men. Rural women have limited access to credit. Although the law guarantees an equal right to inherit, women and girls are often secondary heirs with few rights.

A decade-long unresolved conflict in South Ossetia and Abkhazia continues to jeopardize the population’s ability to maintain livelihoods, and disputes over land are common in these areas. An August 2008 conflict with Russia displaced another 128,000 people and this displacement along with the global financial crisis undermined the government’s poverty-reduction efforts.

Although Georgia has abundant water resources, the water sector suffers from severe contamination, a deficit of drinking water, and low sanitary standards of the water supply system. Sixty percent of existing water pipeline has deteriorated, and sanitary and technical conditions are unsatisfactory. In addition, water distribution is uneven throughout the country. Droughts are common in the eastern region, and irrigation is necessary for agricultural production.

Georgia’s forests are of vital importance to the country’s economy and citizenry. The primary causes of forest degradation are rural poverty and lack of affordable alternatives to wood as heating fuel, as well as the high demand for forest products. Sustainable commercial exploitation, resource conservation, and curbing illegal logging are environmental challenges for the country.

During the Soviet period, Georgia was a source for many minerals. Following the dissolution of the Soviet Union, Georgia’s mineral production fell sharply. Although mineral production began to rise in 2005, Georgia does not produce mineral products in globally significant quantities. The country’s primary role in the mineral sector is as a transport route for oil and gas out of the Caspian region to world markets.

Land

LAND USE

Georgia has a total land area of 69,500 square kilometers and a 2008 population of 4.4 million people. Forty-seven percent of the total population is rural. Agricultural land makes up 43% of total land area. About one- quarter of agricultural land is cropland, and 4% is permanent cropland. Irrigated lands comprise 44% of the total area of cropland. Twenty-five percent of Georgia’s total land area is classified as permanent pastureland and 40% of the total land area is forested. Four percent of the total area is protected (World Bank 2009a; USAID 2005).

Georgia’s 2008 GDP of US $12.7 billion consisted of 10% agriculture, 24% industry, and 66% services. Fifty-four percent of employed Georgians work in the agricultural sector (World Bank 2009a; WFP 2009; Ebanoidze 2002; UN 2007).

Georgia is a low-income, food deficient country. Historically, agriculture has been one of Georgia’s most important sectors due to the country’s diverse climate and relatively good soils. Following dissolution of the Soviet Union, Georgia’s agricultural output declined dramatically due to political instability and the severance of trade ties with other former Soviet republics. As a result, Georgia became a net importer of agricultural products. Continuing threats to food security include drought, severe environmental degradation, and soil salinity (Ebanoidze 2002; WFP 2009; World Bank 2009b).

Twenty-four percent of the population lives in poverty, while a further 9% lives in extreme poverty. Poverty is concentrated in rural areas, which have not benefited from the nationwide economic growth that occurred between 2003 and 2007. Ethnic Georgians, constituting 70% of the population, live throughout the country. The remaining 30% are ethnic minorities consisting of Armenians, Russians, Azeris, Ossetians, Greeks, Abkhaz, Ukrainians, Kurds, Jews, and Assyrians (World Bank 2009a; World Bank 2009b; WFP 2009; IRI n.d.).

At least 220,000 persons have been displaced in Georgia due to conflict in South Ossetia and Abkhazia. Some internally displaced persons (IDPs) have returned to their place of origin while others have been resettled in new villages and apartments. IDPs face inadequate living conditions and limited access to employment opportunities (IDMC 2009).

Approximately 1.1 million hectares of Georgia’s unallocated state-owned land is classified as pasture. Composed of summer and winter pastures, this land is used by communities and families for livestock grazing. The majority of the country’s pastures have not been privatized, and only 48% of state-owned pastureland is leased. A portion of unallocated pastureland is located on the borders of South Ossetia and Abkhazia. Access to pastureland is limited in some areas, which constrains household livelihoods. In conflict-stricken areas, 20% of villages listed access to pastureland as a problem, while 5% did not have access to more than half of their pastureland because of conflict. Pastures suffer from overuse and lack of oversight; many pastures are overgrazed, degraded and produce low yields (WFP 2009).

Two of the country’s priority environmental concerns are desertification and land degradation. These are manifested as wind and water erosion, loss of topsoil, soil contamination by chemicals and radioactive wastes, salinization, bogging, and acidification. Reasons cited for these conditions are the peculiarities of Georgia’s mountainous topography, unsustainable land-management, unsustainable use of water and forest resources, oil and gas operations, low institutional capacity and public awareness, and global climate change (UNDP 2004).

LAND DISTRIBUTION

Prior to land privatization in Georgia, 1300 large state and collective farms controlled the vast majority of the country’s agricultural land, while approximately 700,000 rural households operated smallholdings on a small fraction of the agricultural land (amounting to approximately 200,000 hectares of arable and perennial lands) (Stanfield 2002).

As of 2002, 2 million hectares of agricultural land (approximately 67% of total agricultural land) were still owned by the state, approximately 0.7 million hectares (25% of total agricultural land) were owned and cultivated by private farmers, and 0.3 million hectares  (10% of total agricultural land) were leased by the state to farmers for short terms (3–5 years), medium terms (25 years) or long terms (49 years). The Government of Georgia’s (GOG) vision was that large commercial farms using land leased from the state would provide a robust, market-oriented agricultural sector while smallholder farmers would provide for their own consumption needs. However, only 30% of state-owned agricultural land has been rented, and much of the remainder is uncultivated due to the poor soil, the land’s isolated location, and damaged irrigation and drainage systems (FAO 2008a; Tsomaia et al. 2003).

(10% of total agricultural land) were leased by the state to farmers for short terms (3–5 years), medium terms (25 years) or long terms (49 years). The Government of Georgia’s (GOG) vision was that large commercial farms using land leased from the state would provide a robust, market-oriented agricultural sector while smallholder farmers would provide for their own consumption needs. However, only 30% of state-owned agricultural land has been rented, and much of the remainder is uncultivated due to the poor soil, the land’s isolated location, and damaged irrigation and drainage systems (FAO 2008a; Tsomaia et al. 2003).

As of 2007, average family farm size was 0.7 hectares, with poor households averaging 0.4 hectares and extremely poor households holding 0.2 hectares. The poorest 60% of households spend less than US $2 per day. Among those households living in poverty, 36% report owning no land while among the extremely poor, 50% are landless. Even among landowners, small farm size may in some cases limit the ability of rural households to earn an adequate living from agriculture (World Bank 2009b).

Holders of large land-leases (50 hectares or more) represent 8% of the total number of lessees, but control 56% of leased cropped land (Tsomaia et al. 2003).

LEGAL FRAMEWORK

The Constitution of Georgia (1995; last amended in 2010) recognizes the right to property and prohibits restrictions on the right to acquire, alienate, and inherit property, with a few exceptions (GOG 1995).

As of 2010, laws governing land use and administration include:

- Law on State Property (2010), which abolished the following four laws:

- Law on Privatization of State-Owned Agricultural Land (2005),

- Law on Privatization and Transfer with the Right of Use of State Property and Local Self- Government Unit Property (2007),

- Law on Transfer in Use of State Property, and

- Law on Disposal of Property Acquired by the State;

- Law on Recognition of Title to the Land Plots Possessed (Used) by Individuals and Legal Entities under Public Law (2007, last amended in 2010), which abolished the Law on Acquisition of Non-agricultural Property and Land by Natural Persons and Legal Persons Already in Possession (1998);

- Law on Non-Agricultural Leases (2005);

- Law on Promotion of Leasing Activities (2002);

- Law on Seizure or Expropriation of Property for Urgent Needs (1999);

- Civil Code (1997, arts. 147-315), which governs land transactions and inheritance;

- Law on Agricultural Land Ownership (1996, last amended in 2007); and

- Land Privatization Decree (1992)

(Ebanoidze 2002; GOG 2005; GOG 2007; Reynolds and Flores 2008; Stanfield 2002; APLR 2010).

The following laws govern land registration: the Law on State Registry (2004) and the Law on Public Registry (2008, last amended in 2010) (Fidas and McNicholas 2007; Reynolds and Flores 2008; APLR 2010).

Under the Law on Local Self Government (2002), pastures that were not subject to privatization were declared municipal property. Municipalities were allowed to make lease arrangements on pastures not intended for privatization. However, local municipalities failed to successfully manage the pastures. In August 2010, municipal pastures were transferred back into state ownership (APLR 2010).

The Tax Code (2004) charges the local land administrative unit with setting the land tax rate. Under the Tax Code, the tax rate may range from Georgian Lari (GEL) 8 to 51 per hectare of cropland annually. The tax rate for pastureland ranges from GEL 2.5 to 8 per hectare (Tsomaia et al. 2003; APLR 2010).

TENURE TYPES

Land in Georgia may be privately owned or leased. Although private ownership has increased steadily since the initiation of privatization in 1992, state land ownership dominates in rural areas. Leasing of state-owned property by private individuals and companies is more common than private-to-private leasing transactions. In urban areas, private ownership is the dominant form of tenure (Stanfield 2002).

Rural tenure types can be distinguished on the basis of ownership and scale of operations:

Small-scale farm ownership. As of 2002, this tenure class comprised three groups: (1) families living in villages, but working in nearby cities; (2) families living and working in cities, but who had lived on former collective farms and were able to secure smallholdings in the reform process; and (3) families living and working solely on the farm. Smallholders cultivate 0.81 hectares of land, on average (Stanfield 2002; Gogodze et al. 2007).

Privately owned or leased larger individual farms. These farms are located on privately owned land or land that has been leased from the government by families or groups of families. These families and groups of families lease an average 6 hectares of land from the state (Stanfield 2002; Gogodze et al. 2007).

Corporate farms on leased land. Agricultural enterprises or corporate structures (cooperatives, joint-stock societies, limited-liability companies and other partnerships) are the successors of former state farmers or they are legal entities created since 1992. They lease state land, averaging 93 hectares per enterprise (Stanfield 2002; Gogodze et al. 2007).

Pastureland. Pastureland is state-owned. The entire community has access to pastureland, and villagers rotate their rights to pasture-use (WFP 2009).

SECURING LAND RIGHTS

Starting in 1992, Georgian households began to acquire ownership of small agricultural parcels from the state, free of charge. These landholdings, which have been titled and registered, are generally considered secure. Acquisition of ownership by sale or inheritance is also common. As of 2001, 60% of commercial/industrial land, 100% of urban land with houses, and 85% of urban land with apartments had been privatized (Stanfield 2002; Heron et al. 2001; USAID 2007).

One problem regarding registration of initially privatized rights had to do with faulty surveying: when survey data was transferred to electronic databases, the new records omitted the full extent of the land considered to be held in ownership for many plots. The government attempted to remedy this problem by adopting the 2007 Law on Recognition of Title to the Land Plots Possessed (Used) by Individuals and Legal Entities under Public Law. According to this law and ensuing regulations, lands subject to acknowledgement and registration include: (1) state-owned agricultural and non-agricultural lands possessed in good faith (which could be transferred with no cost to private ownership); (2) lands under use (which can be transferred at a rate of five times the annual land tax); and (3) lands seized or illegally owned (which can be transferred to legal entities at a rate of 100 times the annual land tax for agricultural land and at a normative price for urban land. For physical persons, agricultural land can be transferred at a rate of 10 times the annual land tax, while urban land can be transferred at a rate of 20 times the annual land tax). In the first half of 2008 alone, Tbilisi Municipality received 19,000 applications for land-legalization under the new law; the extent to which the law has been applied to agricultural land is not clear (Egishvili and Ratiani 2008; APLR 2010).

Foreign individuals and companies may buy non-agricultural land in Georgia; only Georgian citizens or companies may buy agricultural land. However, a corporation registered as Georgian that is 100% foreign-owned may purchase agricultural land (USDOS 2008).

Despite efforts to privatize state land, the state still owned 45% of Georgia’s agricultural land in 2007. The State leases out approximately half of its land to private individuals. The law contemplates leases of up to 49 years, but most leases have been much shorter, usually under six years and often under three (Heron et al. 2001; Stanfield 2002; Tsomaia et al. 2003; USAID 2007).

After 2005, municipalities were allowed by law to lease pasturelands. However, local municipalities in charge of administering pastureland were not able to do so effectively and, between 2005 and 2010, only a few lease arrangements were granted. In 2010, municipal pastures were transferred back into state ownership. Under the new Law on State Property, only pastures leased prior to July 30, 2005 became available for privatization. Leaseholders must acquire these lands by May 2011. Other pastures may be leased by the Ministry of Economy and Sustainable Development through auctions or direct leasing (APLR 2010).

As of 2003, 12% of rural households leased state land, as compared to 2% in 1996. Leases of private land were relatively rare. Beginning in 2005, the GOG authorized the privatization of leased state land and unused state land. As of July 2006, 20,000 hectares of these lands had been privatized. By January 2010, over 200,000 hectares of agricultural land had been privatized. The privatization process is still underway (Gogodze et al. 2005; Ebanoidze 2002; USAID 2006; APLR 2010).

The current land-registration system in Georgia is relatively inexpensive, simple, fast, and effective. The registration fee for land registration is GEL 50. To register the sale of land, the buyer must first pay the registration fee at a commercial bank and obtain a receipt. The buyer then must apply to the National Public Registry within 15 days of execution of the sale. The Public Registry may take up to four days to register the sale and issue an Ownership Certificate (Ebanoidze 2002; World Bank 2008a).

Although secured interests in land are recognized and recorded, deficiencies in the court system can hamper realization of property rights. Such deficiencies include judges without adequate training, excessive litigation delays, and potential for bias and corruption (USDOS 2008).

INTRA-HOUSEHOLD RIGHTS TO LAND AND GENDER DIFFERENCES

The Constitution guarantees equal rights for men and women, including in inheritance of property. The surviving spouse, children, and parents inherit on an equal basis. Under the Civil Code, women enjoy rights to conclude agreements on their own behalf, and to own, manage, and dispose of property. Women may independently apply for and receive credit/loans (IHFHR 2000; STOPVAW n.d.; Sumbadze 2008).

The Constitution guarantees equal rights for men and women, including in inheritance of property. The surviving spouse, children, and parents inherit on an equal basis. Under the Civil Code, women enjoy rights to conclude agreements on their own behalf, and to own, manage, and dispose of property. Women may independently apply for and receive credit/loans (IHFHR 2000; STOPVAW n.d.; Sumbadze 2008).

The Civil Code guarantees that spouses enjoy equal rights to property and personal items, and share household responsibilities within a marriage. Property acquired during the marriage is common property, unless otherwise agreed in a prenuptial agreement. The sale of marital property requires the consent of both spouses. Spouses may also have separate property, such as property acquired by one spouse before the marriage, property acquired as a gift during marriage, and personal items acquired during the marriage. There are no legal provisions governing the property of unmarried couples (IHFHR 2000; STOPVAW n.d.; Sumbadze 2008).

Upon divorce, spouses are entitled to an equal distribution of the marital property, unless otherwise agreed. A court may deviate from this principle in the best interests of the children or one spouse (IHFHR 2000).

Despite the relatively favorable legal framework governing women’s access and rights to land, women in Georgia (particularly rural women) lack information about their rights and, as a result, tradition, customary law, and religious law shape attitudes and behavior. Women have little involvement in economic decision-making within the family and do not have the same rights and responsibilities as men. Although women are not legally prevented from accessing credit, in practice rural women have limited access. Although the law guarantees an equal right to inherit, women and girls are often secondary heirs with few rights (STOPVAW n.d).

LAND ADMINISTRATION AND INSTITUTIONS

The National Agency of Public Registry (NAPR), under the Ministry of Justice, was created in 2004, replacing the State Department of Land Management (SDLM) and the Bureau of Technical Inventory. Through its territorial offices, the NAPR provides registry services for immovable and movable property, as well as a real estate cadastre. By 2006, NAPR was self-financed due to increased registrations, a new fee structure, and fund retention at the agency (Fidas and McNicholas 2007; World Bank 2005).

The Ministry of Economy and Sustainable Development oversees the leasing of state-owned agricultural land, with technical support from local employees of NAPR (APLR 2010; Tsomaia et al. 2003).

The Ministry of Economy and Sustainable Development is charged with privatizing agricultural land (GOG 2005).

LAND MARKETS AND INVESTMENTS

Land markets in Georgia, although not fully functioning, are continuing to develop and have become more active in some areas. Following the implementation of land privatization, sales of agricultural land grew quickly, increasing by 70% from 2001 to 2002. Transactions on non-agricultural land increased by 68% in the same period. Land transactions and land prices have continued to take place over the past decade, but at a much slower rate. Transactions in urban land have far outpaced those in agricultural land; only 10% of all land transactions have been in agricultural land. Rural land transactions that do take place often involve lands near to Tbilisi that are used for summer homes or resorts (Ebanoidze 2002; USAID 2005; World Bank 2009b; IFAD 2007).

Changes in the land registration have made titling and registration much simpler. Prior to land market development projects, land registration procedures required over 60 steps, took up to two months and involved extra-legal charges. This process has been reduced to six steps, which can be completed quickly and at low cost. Land registration has also been digitalized, which has made the land market more efficient. Though the previous system did provide titles, it was based on hand-written documents which made secondary and mortgage transactions uncertain. Under the updated system, land-market liquidity increased, and land values, which had been undervalued, were adjusted to more accurately reflect the true market value (IFAD 2007).

Observers cite a lack of access to affordable, long-term credit as a significant hurdle to the development of the agricultural land sales market. Only short term, high-interest (18% per year) credit is generally available, as banks will not accept agricultural land as collateral for mortgage because of the land’s low market value. Agricultural financial institutions and agricultural insurance services do not exist. Credit is more available for transactions in urban areas, where real estate and brokerage companies are well-developed (Egiashvili and Ratiani 2008).

As of 2005, there were 1667 active registered leases on 600,000 hectares of state-owned pastureland. These lands became available for privatization in 2007. Leased plots of pastureland average 112 hectares, though 35% of leases for pasture are for less than 10 hectares. On average, pastureland is taxed at GEL 3 per hectare (USAID 2005; APLR 2010).

COMPULSORY ACQUISITION OF PRIVATE PROPERTY RIGHTS BY GOVERNMENT

The state may expropriate property in order to fulfill a social need, provided that appropriate compensation is paid and the process is consistent with the law, a court order, or (where there is an urgent need) determined by an organic law. The law states that valuation must be carried out by someone with the authorization and qualification to do so. The law provides a mechanism payment of compensation and for court review of the valuation at the option of any party. Compensation may be in the form of property of equal value, as well as money. Compensation must be paid promptly and must include both the value of the expropriated property and the loss suffered as a result of expropriation (GOG 1995; Ebanoidze 2002; APLR 2010).

Pressing “social needs” include the construction of a road or highway, installation of railway tracks, installation of electrical or other utility lines, and other similar projects and activities. The expropriator, who has been awarded the right of expropriation, must agree in advance upon the amount and timing of the compensation to be paid to the owner of the expropriated property (GOG 1995; Ebanoidze 2002; Gvinadze and Keen 2009).

Only a full ownership interest may be acquired by compulsory acquisition, a limitation which some consider to hinder investment, particularly in the energy sector (Gvinadze and Keen 2009).

LAND DISPUTES AND CONFLICTS

Land disputes have undermined confidence in the impartiality of the Georgian judicial system and rule of law. There are many reservations about the competence, independence, and impartiality of Georgian courts. In some cases, lower courts ordered transfer of control of property or of entire enterprises on questionable legal grounds or on the basis of forged documents. Higher courts or the government have reversed some, but not all, of these decisions (USDOS 2008; Wehrmann 2008).

The territories of South Ossetia and Abkhazia are in dispute. Georgia considers them illegally occupied by the Russian Federation, and the Russian Federation, claiming that the territories have proclaimed their independence from Georgia, recognizes their sovereignty. Disputes over land are common in these areas, as some land may rightfully belong to IDPs forced to leave Abkhazia in the early 1990s, and may have improperly been placed on the market by the authorities in Abkhazia. The GOG considers sale of property in Abkhazia illegal, indicating that property may be reclaimed by the original owners at a future date (EU 2009; USDOS 2008).

Pasture use is often a source of dispute in Georgia. Traditionally, pasture access and use were organized by the community to accommodate various users. State leases for pastureland tend to exclude some users from access to pastureland, which has triggered conflict (USAID 2005).

KEY LAND ISSUES AND GOVERNMENT INTERVENTIONS

In 1991, nearly all of Georgia’s agricultural land (3 million hectares) was held by about 1300 collective and state farms. The country began a two-pronged land reform program following independence. The first prong focused on the free transfer of land parcels of up to 1.25 hectares from the state to rural families. The second prong focused on leasing the remaining state lands in larger allotments to physical and legal entities. Following these distribution programs, the state began working on improving procedures for registering rights to the privatized land parcels. By 1999, there was a small class of private owners of agricultural land. However, the leasing portion of the project was reportedly corrupt. Influential government officials received the most fertile parcels, even though they had neither experience nor interest in farming. The original intent of the dual agricultural system – privately owned subsistence farms and large commercial farms on state-owned property – was unsuccessful. The system of granting leases has been biased and, in some cases, corrupt. Large farms are not utilized efficiently or profitably, while subsistence farms may in some cases be too small to be financially self-sufficient given the lack of support for intensive small farm production (USAID 2005; Ebanoidze 2002).

In 2005, the GOG began the third stage of land reform – the large-scale privatization of state-owned land. Under the Law on State Property (2010), current leaseholders were granted a window of time (through May 2011) in which to purchase the land that they held. After that time, the state will have the right to sell the leased lands if leaseholders have not expressed interest in buying them. At the beginning of 2010, over 200,000 hectares of agricultural land, including leased and unused state-owned farmlands, were privatized (APLR 2010).

Through the National Agency of Public Registry (NAPR), the GOG is developing the cadastre and registration system, working on maintenance of registration offices, introducing new registration information technologies and software, and training staff with support and participation of donor-funded projects (NAPR 2009).

In 2007, the GOG launched the 100 Agricultural Enterprises initiative. The initiative seeks to privatize large plots of land (over 50 hectares) and sell them to investors. Investment proposals are evaluated on a competitive basis. Priority is given to investors offering employment, production and export opportunities. The program is open to both domestic and foreign investors (APLR 2010).

Following the 2008 Russia-Georgia conflict, the GOG launched the My House program to record the ownership rights of IDPs from Abkhazia and South Ossetia. Databases for the properties, including land, abandoned by IDPs have been created for Abkhazia and are expected to be created for South Ossetia. The GOG intends to issue special certificates proving IDP’s ownership of the properties. In a separate initiative, the GOG (with support from USAID) granted IDPs ownership of residential and arable land parcels. The average size of residential parcels was to 0.3 ha, while arable land parcels averaged 0.4 ha (APLR 2010).

DONOR INTERVENTIONS

USAID began supporting land privatization in Georgia in 1997. Assistance included providing an assessment of the situation and drafting key legal documents, laws, and procedures for early registration of the newly allocated parcels of both agricultural and non-agricultural land. The US $5.6 million USAID-funded Land Market Development Project (LMDP) began in 2001 and formed a partnership with the State Department of Land Management. Program objectives included: (1) registration of an additional 1.4 million parcels (for a total of 2.4 million total through July 1999); (2) issuance of registration certificates to landowners to ensure secure title; (3) support for land transactions leading to development of a land market; (4) public education and support to landowners; (5) support for additional land privatization; (6) assistance on legal reform; and (7) strengthening capacity of the Association for the Protection of Landowners’ Rights (APLR), among other activities (USAID 2005).

USAID’s US $3.6 million Land Market Development Project II, in partnership with the Association for the Protection of Landowners’ Rights (APLR), extends to 2010 and is intended to complete the agricultural land privatization process, develop a properly functioning land market, and establish a clear, transparent and user-friendly property registration system (USAID 2008).

USAID also supported a three-year legislative initiative to provide restitution to people who lost property in the South Ossetian conflict. The results included a completed database of 4,890 abandoned properties along with property claims, as well as an outreach and consultation program for affected parties (APLR 2009a).

In 2009, USAID announced the Georgia Agricultural Risk Reduction Program (GARRP), a multi-phase program that was implemented as part of the US Government’s immediate humanitarian response to the August 2008 conflict. GARRP has addressed the needs of around 40,000 farm families from conflict-ridden areas by providing livelihood assistance to local farmers and resettled IDPs who have been issued agricultural land (USAID 2009a; CNFA 2009).

The Land Registration Component of the World Bank’s Agricultural Development Project established land registration offices in two districts close to the capital, registered around 170,000 land parcels, and issued 155,000 land titles. The project refurbished and computerized 11 regional and 37 district registries countrywide. The project also supported the transition of registration responsibilities from the State Department of Land Management to the National Agency for Public Registry (NAPR 2009).

Other donor support for land registration included a project funded by Kreditanstalt fur Wiederaufbau (KfW) for mapping, cadastral surveys, and the establishment of six registration centers. The United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and the European Union (EU) funded cadastral surveying and registration in one district, as well as software development and the refurbishment of 11 district offices. The Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (SIDA) funded capacity-building by establishing a training center for government employees working on land registration, land information systems, cadastral surveys, valuation, credit marketing, and office management (Ebanoidze 2002).

The German Agency for Technical Cooperation (GTZ) implemented a six-year Land Management in Georgia project with the Ministry of Justice. Focusing on registration of urban land and apartments, the project completed cadastres for several cities, and the project focused on the development of urban zoning plans (GTZ 2009).

The Association for the Protection of Landowners’ Rights (APLR), a Georgian NGO, contracts with USAID on the Land Market Development Project II and, since 1996, has engaged on many levels in land privatization. As part of the project Endowment for Community Mobilization Initiative in Western Georgia, the APLR assisted villages in forming community-based organizations (CBOs) to manage pasturelands. Part of the International Land Coalition’s Community Empowerment Facility (CEF), the project targeted five villages in one region, each of which formed CBOs with members from village communities (APLR 2009b; Bokeria 2004).

Freshwater (Lakes, Rivers, Groundwater)

RESOURCE QUANTITY, QUALITY, USE AND DISTRIBUTION

Georgia has the richest water resources in the South Caucasus. There are two main river basins: the Black Sea basin in the west and the Caspian Sea basin in the east. There are 43 dams, most in the east and used primarily for irrigation of fruit trees and grapes, pasture and fodder crops, vegetables, potatoes, wheat, maize and sunflowers and hydropower rather than for potable water supply (FAO 2008a).

In 2005, 66% of Georgia’s water sources were from surface water and 34% were from groundwater. Irrigation and livestock generated the most withdrawals at 65%, whereas 22% went to municipal use and 13% to industry. Ninety-three percent of the irrigation systems are surface irrigation and 7% are localized irrigation, in which water is distributed via a network of pipes (FAO 2008a).

Water distribution is uneven throughout the country due to the range of precipitation in the humid west and semi-arid east. In the eastern region, droughts are common and irrigation is necessary. The water sector suffers from contamination as a result of the deterioration of the sewage system and agricultural wastes, a deficit of clean drinking water, and low sanitary and technical standards of the water supply system. Sixty percent of existing water pipelines have deteriorated, and sanitary and technical conditions are unsatisfactory. Due to network damage, large quantities of water are lost: in 1999, 40% of the household water supply was lost. Water supply in the east also suffers from severe to moderate saline contamination due to a dilapidated irrigation system. Only 16% of the rural population had access to safe drinking water in 2009 (FAO 2008a; UNECE 2003; UNDP 2009).

LEGAL FRAMEWORK

Although Georgia has no comprehensive national water policy, over a dozen laws relate to the management and protection of Georgia’s water resources and related environmental issues; the most important of these is the 1997 Law on Water (as amended 2000). The Law on Water governs pollution control, protection of drinking water, licensing of water use and discharge, categorization of and protection of resources, and flood control, among other topics. The Law on Water states that water protection is a major element of environmental protection for Georgian citizens; drinking-water has the highest priority; both groundwater and surface water are under state control; management of water varies depending on its hydrologic importance; and pollution is restricted. Multiple legislative orders, decrees, and regulations supplement this law (FAO 2008a; UNECE 2003).

A 2006 draft concept paper on a national water policy identifies the government’s primary goal as ensuring effective water management within the next 25 years. In addition, the paper identifies the following priorities: maintaining ecological value and functions of water resources; maintaining quality and quantity; ensuring access to safe drinking water; and maintaining the hydrological regime and undertaking flood and drought-prevention activities (GOG 2006a).

TENURE ISSUES

Water is the property of the state and under the control of the national government (GOG 2006a; FAO 2008a).

The Law on Water provides for the licensing of water use and discharge of pollutants. Licenses for municipal water systems and irrigation are for 25 years, and those for wastewater discharge are for 3 to 5 years. As an exception to this, facilities in place before 1999 operate under a system of allowable limits. Under both systems, users pay a fee to withdraw clean water and to discharge wastewater. If discharge is above allowable limits, users pay a proportionally higher fine. Self-reporting is used with minimal government oversight. Requirements for permits for water withdrawal have recently been suspended (UNECE 2003; UNDP 2009).

As of 2003, no municipal wastewater treatment plants were operating under a license. The 27 industrial facilities under license represented only 5% of the total wastewater generated by industry (UNECE 2003).

GOVERNMENT ADMINISTRATION AND INSTITUTIONS

Soviet-era institutional arrangements for water supply and sanitation remain unchanged. Water utilities are state agencies and the majority of funding comes from state budgets (EUWI 2005).

The Ministry of Environment and Natural Resources Protection is responsible for implementing the Law on Water, although other ministries play roles in specific areas. In conjunction with the Centre for Monitoring and Prognostication, the Ministry is responsible for assessing the quantity and quality of surface water and groundwater (FAO 2008a).

The Ministry of Economic and Sustainable Development is tasked with developing a water sector policy, setting water service standards, and mobilizing financing for the sector. The National Energy and Water Supply Regulatory Commission has been responsible for approving water tariffs (ADB 2008).

The Ministry of Labor, Health, and Social Affairs sets standards for drinking water, recreational use, and wastewater used for irrigation (UNECE 2003).

The Ministry of Food and Agriculture, with the Department of Melioration and Water Resources, is responsible for planning, monitoring, and promoting irrigated agriculture (FAO 2008a).

The Ministry of Finance sets water use and emission rates that are incorporated into licenses issued by the Ministry of Environment and Natural Resources Protection (UNECE 2003).

The effectiveness of these institutions is constrained due to their lack of basic tools to monitor compliance. Additionally, government has no authority to conduct on-site inspections unless by court order (UNECE 2003).

GOVERNMENT REFORMS, INTERVENTIONS AND INVESTMENTS

With support of the EU, the GOG is creating a single comprehensive legislative framework governing water resources. The government is also developing guidelines for water and wastewater tariffs that will promote economic use of resources and meet financial obligations, including full cost-recovery and profitability (ECBSea 2009; ADB 2008).

DONOR INTERVENTIONS AND INVESTMENTS

The Asian Development Bank (ADB) has authorized a US $30 million loan for a Municipal Services Development Project, scheduled through 2013; the project is intended to increase the effectiveness of municipal governments in identifying, planning, delivering, and recovering costs of municipal infrastructure and services, including water. The total cost of the proposed project is US $41.5 million, which includes central and municipal government support (ADB 2008; ADB 2009a).

The ADB is also providing technical assistance under the US $863,000 project, Urban Water Supply and Sanitation Sector Strategy and Regulatory Framework, intended to support development of a water and wastewater policy framework (ADB 2009b).

As part of Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC)’s support through 2011, the Regional Infrastructure Development Activity rehabilitated the water supply network of the major port city of Poti; related works by partner donors are ongoing. Rehabilitation of the water supply systems also is underway in two other areas (MCC 2009; EBRD 2006).

Between 2000 and 2002, USAID implemented the South Caucasus Water Management Project to strengthen cooperation among water agencies at the local, national, and regional levels, and demonstrate integrated water resources management (FAO 2008a).

Trees and Forests

RESOURCE QUANTITY, QUALITY, USE AND DISTRIBUTION

Forests are of vital importance to Georgia’s economy and citizenry. Forests cover the Greater Caucasus Mountains and the Lesser Caucasus. Forty percent of Georgia’s land area is forested, with 87% of forests located on slopes. Over 80% of the forests are broadleaves (almost 50% beech), and 20% are conifers. In terms of biodiversity, Georgia’s forests contain more than 4100 of the estimated 6350 species in the entire Caucasus region, including 395 species of woody plants (FAO 2008b; Torchinava 2005).

Since independence, forests have been under severe pressure from illegal and unsustainable logging, poor management practice, and overgrazing. The primary causes for forest degradation are rural poverty and lack of affordable alternatives to wood as heating fuel, as well as the high demand for forest products, regardless of whether the produces were obtained in an illegal manner. Maintaining sustainable commercial exploitation while conserving forest resources and checking illegal logging is a key environmental challenge. There is no reliable source on the specific volume of illegally harvested wood, but experts’ estimates vary between 2.5 and 8 million cubic meters per year. An estimated 60% of the annual forest harvest goes unrecorded. Soil degradation and erosion are also serious problems. The main reasons for these problems are the topography, heavy rainfall, and overgrazing by livestock (FAO 2005a; GOG 2006b; Torchinava 2005; FAO 2008b).

Before independence, most of the wood used for construction and pulp production was imported from Russia. With the dissolution of the Soviet Union, this trade became uneconomical; it was phased out, and Georgia’s processing enterprises practically stopped operating (FAO 2008b).

Reliable economic data on the forestry sector is scarce. One report estimates that the sector accounted for 4% to 5% of GDP during the Soviet period. While the size of the sector has decreased, there is substantial room for growth, provided forests are managed sustainably. Georgia’s forests also produce a range of non-wood products such as fruit, berries, nuts, bark, mushrooms, medicinal plants, honey, and decorative plants. In addition to its wood and environmental functions, Georgia’s tourism industry is primarily in forested areas (FAO 2008b).

LEGAL FRAMEWORK

There is no national forest policy in Georgia. The 1999 Forest Code establishes the legal basis for forest protection, use, and restoration of the country’s forest resources. The Code’s primary objectives include the protection and sustainable development and management of forests, as well as a shift in forest management from central planning to market-based management. The World Bank indicated that the Code has been improved, but it needs further amendments to improve its application and transparency (Torchinava 2005; World Bank 2002; CEE BankWatch 2007).

Forest regulations require the state to prepare forest inventories and management plans every ten years. However, in 2002 only 17% of the forest estate had updated forest management plans (World Bank 2002).

TENURE ISSUES

The Forest Code allows for multiple forms of forest ownership including state, municipal/community, church, and private ownership. The code also allows for the long-term lease of state forests. Licenses to use-rights for state forests are auctioned. The only exception to the license requirement is use by households for fuelwood. Most commercial forest loggers are private and do not have long-term rights to the forested land. As a result, commercial loggers tend to be focused on short-term monetary gain rather than medium-term sustainability of their forest operations (World Bank 2002; GOG 2006b).

GOVERNMENT ADMINISTRATION AND INSTITUTIONS

Several state agencies are responsible for forest policy and management. The Ministry of Environmental Protection and Natural Resources is responsible for environmental protection and regulation of natural resources. The Ministry reviews sectoral plans, approves forest management plans, and monitors forest operations to ensure compliance with permit conditions, among other duties. Within the Ministry, the Department of Biodiversity Protection oversees biodiversity conservation. The Ministry also issues licenses for forestry exploitation (FAO 2005b; FAO 2007).

The State Forestry Department (SFD) and its local offices are responsible for developing forest policies and strategies and managing forest resources. The SFD reports directly to the President of Georgia and holds ministerial status. The SFD is comprised of forest enterprises, some of which undertake forest inventory and management plans (FAO 2005b; FAO 2007; World Bank 2009c).

GOVERNMENT REFORMS, INTERVENTIONS AND INVESTMENTS

In 2008, the GOG suspended issuance of logging licenses. In March 2009, the government announced that it would inventory the country’s forests and that the Ministry of Economic Development would begin issuing 10- to 20-year logging licenses (Georgian Business Week 2009).

In 2007, the GOG launched a large-scale reform of the forestry sector intended to transfer responsibility for forest management and maintenance using long-term leases (up to 50 years). Few reforms were implemented, however, though the Forestry Department was restructured and reorganized and 12 long-term leases were auctioned (Macharashvili 2009).

In a 2006 concept paper, the Ministry of Environmental Protection and Natural Resources articulated the government’s position on the reform of the management and use of state forests. Principles cited included: sustainable management; the setting aside of protected forested areas; use of comprehensive management plans; use of long-term leases; and harmonization of forestry legislation with the country’s commitments in international agreements (GOG 2006c).

DONOR INTERVENTIONS AND INVESTMENTS

USAID works with the GOG to promote the tourism sector through the conservation of biodiversity in natural and managed ecosystems. USAID supports the establishment of new national parks, building the institutional capacity of the national government to manage protected ecosystems, and enhancing regional collaboration on protected areas. Among other things, USAID assisted with the designation of the new 25,000-hectare Tbilisi National Park and the incorporation of best practices in park management (USAID 2009b).

From 2002 to 2008, the World Bank assisted the GOG in establishing a forest management system that maximizes contribution of Georgia’s forests to economic development and rural poverty reduction on an environmentally sustainable basis. Activities included a forest inventory, community forest pilots, a nursery, and reforestation and afforestation activities. The project and the government’s actions were heavily criticized by the NGO community for moving forward without a National Forest Policy, among other reasons. Although the project was scheduled through 2009, the GOG announced a new forest policy that was counter to the sustainable principles of the project and decided to suspend work on project activities in 2007. The GOG subsequently began auctioning long-term leases that did not conform to sustainable forest management principles. The Bank outlined elements for forest leasing and related regulations, which were minimal requirements for continued Bank engagement. The GOG was unable to meet these requirements, and the Bank cancelled the project in 2008 (World Bank 2008b; CEE BankWatch 2007; World Bank 2009c).

From 2001 through 2008, the World Bank provided US $9.5 million to conserve biodiversity through the creation of three ecologically sustainable protected areas in forest ecosystems in eastern Georgia, and to build capacity for mainstreaming biodiversity conservation into production landscapes. The Bank reported that the project made progress in creating and improving the management of national protected areas (World Bank 2008b).

Minerals

RESOURCE QUANTITY, QUALITY, USE AND DISTRIBUTION

Georgia possesses more than 300 explored mineral deposits, about half of which have been brought into production. Georgia has 11 oilfields with a reported 28 metric tons (28,000 kilograms) of oil resources. Larger oilfields are thought to exist. Georgia also has more than 400 metric tons (400,000 kilograms) of coal resources and the Black Sea Coast is believed to have large gas fields ranging from 8.5 billion to 125 billion cubic meters of resources. A number of major international companies are assessing the region’s production potential (Levine and Wallace 2005).

During the Soviet period, Georgia was a source for arsenic, barite, bentonite, coal, copper, diatomite, lead, manganese, zeolite, and zinc, among other minerals. Most minerals continue to be produced, but in smaller quantities. Following the dissolution of the Soviet Union, Georgia’s mineral production fell sharply due to increased political instability and a decline in regional trade. Nearly 150 mining and quarrying enterprises operate in Georgia, of which seven are state-owned. State-owned enterprises contribute about one-third of the sector’s production. The remaining two-thirds are produced by private enterprise, which contributed 10% of the country’s 2005 industrial production. Although production began to increase in 2005, Georgia does not produce globally significant quantities of these minerals (Levine and Wallace 2005).

Georgia’s primary role in the mineral sector is as a transport route for oil and gas shipments out of the Caspian region to world markets. There is no domestic gas production, and Georgia imports oil and gas for domestic consumption (Levine and Wallace 2005; Kipiani et al. 2008a).

Three major oil and gas export pipelines pass through Georgia – the Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan (BTC) Oil Pipeline, the South Caucasus (SCP) Gas Pipeline, and the Baku-Supsa Pipeline – and are expected to provide a significant source of revenue for the country. The BTC Pipeline runs through Azerbaijan, Georgia and Turkey and is managed by an international consortium headed by British Petroleum (BP) and called the BTC Company. The South Caucasus Gas (SCP) Pipeline (also called the Baku-Tbilisi-Erzurum Pipeline or the Shah-Deniz Pipeline) also runs through Azerbaijan, Georgia and Turkey. The SCP Pipeline is owned by the SCP partners, headed by BP. The Baku-Supsa Pipeline, operated by BP, transports Azerbaijan oil from Baku to Supsa, a Georgian port on the Black Sea. It serves as a backup to the BTC (CEE Bank Watch 2006; Kipiani et al. 2008a; EBRD 2002; US- EIA 2009).

LEGAL FRAMEWORK

The Law on the Subsurface governs the licensing and usage of minerals, the rights and duties of the producer/investor, and the main regulatory bodies. The 1996 Law on Environmental Permits provides the basic principles for issuing environmental permits. The Law on License and Permit Fees establishes fees for certain permits and licenses. The Law on Safety of Hazardous Industrial Objects establishes the status and safety requirements for hazardous industrial objects. The 1996 Law on the System of Protected Areas provides some restrictions on the exploration and use of natural resources in national parks and other protected areas (Kipiani et al. 2007; Kipiani et al. 2008b).

The 1999 Law on Oil and Gas governs the exploration, storage, and transportation of natural gas and oil. It also mandates safety and environmental requirements. The 2002 Order of the Head of the State agency for Regulation of Oil and Gas Resources (9 January) provides detailed rules for carrying out oil and gas activities. The 2002 Order of the Head of the State Agency for Regulation of Oil and Gas Resources establishes rules for determining the price for oil and gas operations. The 2004 Law on Fees for Usage of Natural Resources establishes the royalty rate. The 1997 Law on Electricity and Gas establishes rules for the licensing of gas supply, transportation, and distribution (Kipiani et al. 2008a; Kipiani et al. 2007).

TENURE ISSUES

The state owns all subsurface minerals. Ownership of the land does not confer rights to subsurface minerals (Kipiani et al. 2008b).

The Law on the Subsurface divides non-hydrocarbon mineral reserves into two groups: (1) minerals of state significance; and (2) minerals of local significance. Minerals of state significance include mineral deposits whose development are of special economic importance to the state and directly linked with maintenance and development of certain social infrastructures. The Ministries of Economic Development and of Environmental Protection and Mineral Resources establish the lists of minerals of state and local significance (Kipiani et al. 2008b).

The state may grant parties the right to research minerals, conduct mining activities, explore and produce minerals, and recycle and use mining waste products. Such rights are granted via licenses available by auction (Kipiani et al. 2008b).

For oil and gas, the government will enter into a variety of agreements granting an investor the right to prospect and exploit oil and gas resources. A risk service agreement grants the investor the right to conduct oil prospecting in a certain area for a specified period. Under a production-sharing agreement, the GOG grants an investor the exclusive right to conduct oil operations in a defined area for a determined period. A service agreement governs other related oil or gas operations, e.g., refining. Within one month of execution of these agreements, the state grants the investor a license for use of oil resources. The length of an agreement and license is typically 25 years, renewable for up to five years (Kipiani et al. 2007; Kipiani et al. 2008a).

GOVERNMENT ADMINISTRATION AND INSTITUTIONS

For the energy sector (including oil and gas), the Ministry of Energy sets overall government policy and programs. The Ministry of Economic Development is responsible for issuing licenses for minerals exploration. The Service of Environmental Protection at the Ministry of Environmental Protection and Natural Resources regulates the environmental, health, and safety standards applicable to the mining industry (Kipiani et al. 2007; Kipiani et al. 2008b).

The State Agency for Regulation of Oil and Gas Resources of Georgia regulates oil and gas operations, including refining and transport. The Agency is responsible for the negotiation and award of agreements and licenses for oil and gas operations. The National Commission on Energy and Water Supply is an independent regulatory body responsible for licensing natural gas transporters and distributers (Kipiani et al. 2007; Kipiani et al. 2008a).

GOVERNMENT REFORMS, INTERVENTIONS AND INVESTMENTS

The GOG has been responsible for negotiating the agreements necessary to support the oil and gas pipelines, as well as for negotiations for domestic energy supply from the pipelines. The GOG has also participated in multilateral trade initiatives regarding the pipelines, such as the Baku Initiative, which was launched in 2004 to support energy development and trade between Black Sea and Caspian Littoral States and their neighbors on one hand and the EU on the other (Patsuria 2008; EC 2006; EC 2009).

Seven state-owned enterprises contribute approximately one-third of the mining sector’s total production (Levine and Wallace 2005).

DONOR INTERVENTIONS AND INVESTMENTS

The World Bank recently completed a US $12.32 million project to help enhance the government’s capacity to negotiate and implement oil and gas transit agreements to maximize economic benefits, and minimize social and environmental costs (World Bank 2008b).