Overview

Poor resource governance has been both the cause and result of conflict, instability, and poverty in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) for more than a century. Improving the governance of the country’s significant natural resource base is critical to achieving greater prosperity, sustaining it, and ensuring that it benefits the nearly 65 million people living there. But better resource governance is an enormous challenge, demanding: vision and leadership from government leaders at all levels, even as conflicts continue in the country’s eastern regions and corrupt practices persist; major investments in physical and institutional infrastructure, supported by appropriate laws and regulations; and the application of substantial technical expertise in mining, forestry, agriculture, and the maintenance of ecosystem services in the world’s second-largest tropical forest.

An initial possible area of focus for better governance is the mining sector, where the DRC has huge potential for export expansion and wealth generation that could benefit the nation as a whole in the relatively short term. To date, however, the sector has been marked by corruption, political interference in parastatal mining companies, lack of institutional capacity, and policies that have constrained investment not only in mining but in value-addition in DRC. Small-scale and artisanal miners produce most of the country’s gold, tin, and tungsten and were responsible for 70% of the country’s diamond production in 2009. Artisanal miners work under difficult conditions with little capital and are subject to periodic violence and conflict as militias seek to tap the sector for funding.

With growing recognition of the role that the Congo Basin will play in global efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions through reducing emissions from deforestation and forest degradation (REDD) and REDD+ (enhancing existing forests and increasing forest cover through conservation and sustainable management of forests), it is likely that greater attention to environmental governance will also come quickly to the fore. Many donors are already supporting the Congo Basin Forest Partnership (CBFP), providing a solid starting point for further efforts to enable forest-dependent populations (perhaps as many as 40 % of rural Congolese) to better manage the resource, but more needs to be done by the DRC government to sort out its timber concession agreements and monitor the exploitation of this globally critical resource.

Greater production in agriculture, currently the leading sector of the economy in terms of contributions to GDP, also depends upon improvements in resource governance and property rights. Waves of population displacements due to conflict and violence have affected the highly productive zones in eastern Congo, and many people have moved into more fragile ecosystems. The years of conflict have also degraded the national road infrastructure and reduced access to markets, driving farm families back to a subsistence standard of living. Nearly a quarter of the population lives in urban and peri-urban areas, where ongoing projects are creating and rehabilitating the infrastructure needed to supply safe water, sanitation, and electricity. The population supports a thriving, intensive agricultural sector, but reliance on untreated urban wastewater for irrigation threatens food safety. More significantly, 80% of disease in the DRC and one-third of all fatalities are related to contaminated water.

Donors have increased their support for development in the DRC in recent years, and the upward trend is likely to continue, driven by the poverty and human needs of the country, the huge business opportunities, and the high international priority attached to conservation of the Congo Basin ecosystem. Continued poor governance of the country’s natural resource base, however, will limit the impact of this support and may perpetuate the cycles of exploitation, violence, and conflict that have thus far prevented the population from sharing in the nation’s wealth and promise. Donors, including USAID, will need to work together to reverse the patterns of the past.

Key Issues and Intervention Constraints

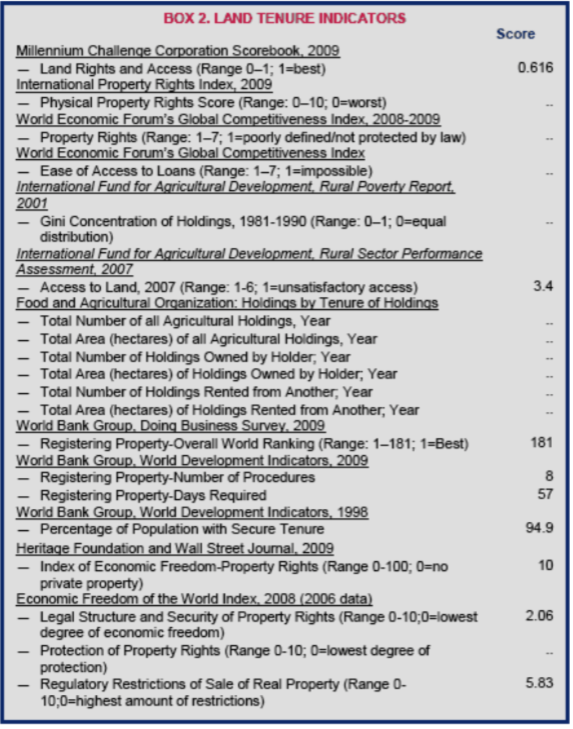

The DRC is a candidate for a new or substantially revised legal framework for land, especially land used for agriculture. The current system provides little security to landholders and does not foster productive and sustainable use of the land. As road infrastructure is built for purposes of mineral and timber exploitation in the coming decade, new lands may be opened (or re-opened) for commercial agriculture, and tenure issues may become acute. Addressing land tenure issues may also prove essential for stabilizing populations suffering from violence and displacement; customary law is fragmented and very localized and appears to be inadequate to deal with the current complex situation. Donors supporting agricultural development, including USAID, could undertake focused assessments in priority regions and use expertise gained from working in other post-conflict African countries to identify areas where, in the short term, donors might help the government implement appropriate existing law. A longer term effort could assist the government to design a legal framework that provides for secure access to productive land (with special attention to access for women and marginalized populations), and establishes an effective framework for land administration. Expertise developing effective legal frameworks in pluralistic legal environments with strong customary interests will be especially useful.

Numerous parties have been engaged in helping the DRC with forest resource issues over the last several years. Working groups have identified the need for implementation of national policies that advance the livelihoods of forest-dependent communities, help secure their rights to the land and resources, develop mechanisms for participatory community involvement, map community forest resources, and develop forest management plans. USAID is working with the government to design and implement pilot projects that focus on the development of effective community involvement in forest governance. Based on the emerging experience in the DRC and other Basin countries, USAID and other donors can help develop model techniques and tools for community resource mapping, community-based forest management plans, and recognition of the rights of women and minority populations to use of forest resources. The pilot program experience and developed models and tools will be valuable to forest policy and implementation efforts at both national and Basin level.

Both the formal and customary systems of land-dispute resolution in the DRC are facing significant challenges to their effectiveness, especially in protecting the rights of populations who now live in forest and agricultural areas subject to REDD/REDD+ considerations and of those populations that have been displaced through conflict and continuing violence. Donors could conduct an assessment of the existing formal and customary institutional structures and assist the government in evaluating options for structuring a more effective and accessible dispute resolution system for land issues that harnesses the capacity and social legitimacy of customary structures, to the extent appropriate, but recognizes the new demands for these resources that will have to be taken into account. USAID’s diversity of projects throughout the country provides access to local information that could assist in designing and implementing pilot projects to test land- dispute resolution systems and, ultimately, help inform the development of countrywide systems.

Expansion of industrial mining operations over the next ten years is widely seen as desirable for providing an important boost to the DRC economy. Artisanal mining is also likely to continue, and perhaps expand, as recovery from the global recession that dampened demand in 2009 takes hold. Many recommendations have already been made with regard to improving the governance and supervision of both industrial and artisanal operations to reduce corruption and violence, increase transparency, and ensure that benefits are widely shared among the population. However, expansion of mining will have significant impacts outside of the mining areas as well: pollution of water resources used for processing ore, construction of new roads to facilitate evacuation of ore, and movements of populations to provide labor for the operations (implying also expanding land-use for food production in adjacent areas). Experience to date indicates that these factors are likely to have serious effects on both human and environmental health. Donors should assist the DRC to ensure that governance, supervision, regulation and monitoring of mining operations are sufficiently broadened to include attention to these areas. Donors may be able to support government efforts by helping other civil society organizations develop or strengthen their capacity help to ensure that government oversight is effective.

Summary

The Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), also known as Congo (Kinshasa), is still emerging from a decade of violent conflict. From the time that foreign-based rebel forces ended President Mobutu’s 32-year rule in 1997 to Joseph Kabila’s election as President and establishment of the National Assembly in 2006, the war in the DRC involved no fewer than nine foreign powers and caused the deaths of 3.5 million people (many due to malnutrition and illness) and displacement of another 2.4 million. Much of the country’s transport infrastructure was destroyed or lost to disrepair. A culture of violence and conflict, corruption, and mismanagement permeated government. The new government is in the process of establishing itself, rebuilding administrative systems, regaining control of areas governed by warlords and militia groups, and is committed to setting standards of good governance.

The DRC is distinguished by the diversity and scale of its natural resources, including 2.2 million square kilometers of land, an area roughly equivalent to the territory of western Europe. More than half of the country’s land is forest, constituting the second-largest contiguous area of tropical forest in the world and the habitat for animals and plants found nowhere else. If harnessed for hydroelectricity, the DRC’s water resources could supply the energy needs of southern Africa. The country also has abundant mineral deposits, including cobalt, copper, diamonds, and gold.

In spite of these rich natural resources, the people of the DRC have realized few of the benefits. Corrupt leaders have siphoned off the wealth for personal gain. Rebelling militias have claimed resources to buy arms and fuel the conflicts for control of territory. The years of war degraded and destroyed market infrastructure, and agriculture was reduced to subsistence farming. Agriculture still contributes more than 40% of the nation’s GDP, but 73% of the population is malnourished. An estimated 80% percent of the population of 64 million people currently lives on less than US $1 per day.

In spite of these rich natural resources, the people of the DRC have realized few of the benefits. Corrupt leaders have siphoned off the wealth for personal gain. Rebelling militias have claimed resources to buy arms and fuel the conflicts for control of territory. The years of war degraded and destroyed market infrastructure, and agriculture was reduced to subsistence farming. Agriculture still contributes more than 40% of the nation’s GDP, but 73% of the population is malnourished. An estimated 80% percent of the population of 64 million people currently lives on less than US $1 per day.

Under the formal law, the state owns all the DRC’s natural resources (land, water, forests, and minerals); people can obtain various types of use and exploitation rights under an evolving set of laws and regulations. In practice, customary law endures, and natural resource rights are subject to parallel, incomplete, and often contradictory systems of formal and customary law. Land rights are often ambiguous, usually undocumented, and tenuous. Agricultural land is subject to seizure and land-grabbing. Formal and customary institutions are often ill-equipped to resolve land disputes. A large share of the rural population relies on the forests for their livelihoods, but the encroachment of displaced populations into protected areas, harvesting of bushmeat and firewood, and widespread illegal logging have contributed to the degradation of the forest resources on which they depend.

Corruption, an inadequate legal framework, and lack of institutional capacity have prevented the DRC’s population from benefiting from the country’s substantial mineral wealth. An effort to bring mining concessions made during the years of war into legal compliance has had little, if any, impact. Some observers nonetheless predict that renewed investment in the mining sector is likely to be the DRC’s best opportunity for increasing revenues within the next decade. The global recession of 2008-2009 caused a slowdown in many investments, but global demand for the copper, cobalt, and other minerals held in the country’s territory is expected to return and drive the sector forward again. The challenge for the government will be to provide better governance and oversight for these important national resources and ensure that the benefits are transparent and widely shared.

Land

LAND USE

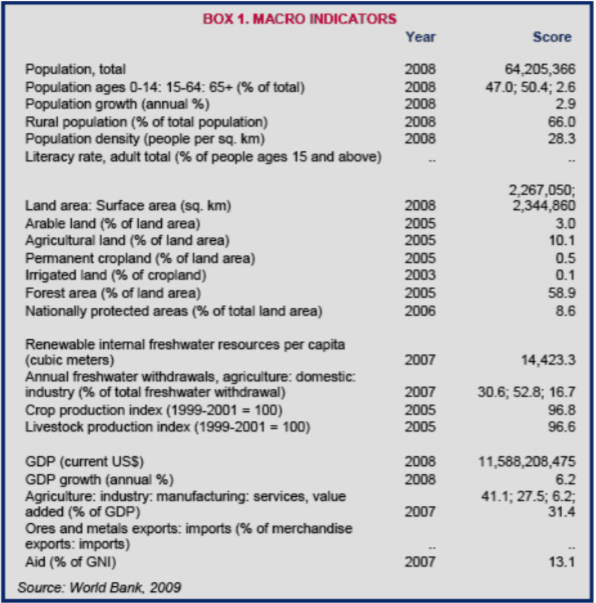

The DRC is the third-largest country in Africa (after Sudan and Algeria) and has a total land area of 2,267,000 square kilometers. The estimated 2008 population of 64 million included representatives of over 250 ethnic groups, most of which are of Bantu origin. Approximately 66% of the population is rural and 34% urban. Total GDP in 2008 was US $11.5 billion, with 41% attributed to agriculture, 28% to industry, and 31% to services. Since 2002, a recovery in the mining sector and higher investment in copper, cobalt, and zinc mining have driven GDP growth (World Bank 2009a; World Bank 2008b; GODRC 2007). Livelihoods in the DRC have been adversely impacted by the years of violent conflict, collapse of the economy, mismanagement of natural and financial resources, and corruption. Life expectancy is 46 years for men and 51 years for women. Only 56% of women are literate, and maternal mortality is the highest in the world. Eighty percent of the population lives on less than US $1 per day. One-third of the population only eats once a day and 73% suffers from malnutrition. In 2001, only 4% of the population was employed in the formal sector (USAID 2005; ICG 2006; FAO 2005).

Ten percent of the DRC’s total land area is classified as agricultural land; 3% is arable, and only 0.1% of cropped land is irrigated. Much of the most fertile agricultural land is found in the plateaus in the Katanga region in the southeastern section of the country. Sixty-one percent of the population is engaged in agriculture, which, due to the destruction and deterioration of market infrastructure during the war years, has become primarily focused on smallholder subsistence farming. Agricultural production does not meet the country’s food needs, and 11% of cereals are imported (World Bank 2009a; FAO 2005; Counsell 2006). The DRC’s major crops vary by region, but maize and manioc (cassava) are staples in most of the country, and most areas support livestock production. Wheat, beans, potatoes and cash crops of coffee, tea, and quinine are grown in eastern regions (now Ituri and North Kivu provinces). Rice and groundnuts are grown in Maniema Province. Shifting cultivation is practiced in northern provinces (formerly Equateur Province), and, in addition to maize and manioc, subsistence farmers grow groundnuts and squash. In the north-central forest-savannah region (formerly Province Orientale, now Tshopo, Bas-Uele, and Haut-Uele) farmers grow rice, bananas, and groundnuts. Prior to the war, the province also had commercial coffee, cocoa, and rubber farms. The southwestern provinces (Kinshasa, Kongo Central, and Kwango), which serve Kinshasa markets, produce fruits, vegetables, and beef (WCS 2003).

Fifty-nine percent of the DRC’s total land area is forested, and 8.6% of total land area is designated as nationally protected areas. More than half of the larger Congo Basin forest area is located in the DRC. As the second-largest expanse of tropical forest in the world (after the Amazon Basin), the Congo Basin is a global as well as national resource. The estimated annual rate of deforestation is 0.2-0.3%, with 400,000-500,000 hectares of closed forest lost per year. The years of violent conflict have resulted in an unprecedented degradation of natural resources, displacement of people into fragile ecosystems, and the breakdown of local institutions governing customary access to natural resources, leading to overuse and looting. People escaping violence have migrated into remote territories, resulting in degradation of some of the world’s most biodiverse areas (World Bank 2009a; FAO 2005; CIFOR et al. 2007; Counsell 2006; Global Witness 2007).

Fifty-nine percent of the DRC’s total land area is forested, and 8.6% of total land area is designated as nationally protected areas. More than half of the larger Congo Basin forest area is located in the DRC. As the second-largest expanse of tropical forest in the world (after the Amazon Basin), the Congo Basin is a global as well as national resource. The estimated annual rate of deforestation is 0.2-0.3%, with 400,000-500,000 hectares of closed forest lost per year. The years of violent conflict have resulted in an unprecedented degradation of natural resources, displacement of people into fragile ecosystems, and the breakdown of local institutions governing customary access to natural resources, leading to overuse and looting. People escaping violence have migrated into remote territories, resulting in degradation of some of the world’s most biodiverse areas (World Bank 2009a; FAO 2005; CIFOR et al. 2007; Counsell 2006; Global Witness 2007).

LAND DISTRIBUTION

During colonial times, only Europeans were permitted to own land on a private basis; all other land was governed by traditional rulers as communal land subject to customary law. The vast majority of Congolese lived in rural areas and received land allocations from traditional authorities. Over time, land allocations became increasingly individualized, and informal land transactions became common in some areas. During President Mobutu’s post-Independence reign (1965–1997), all land in the DRC was officially nationalized, but the system of customary land tenure continued to operate parallel to the formal system. In urban areas, some plots are held under formal, long-term concessions granted by the state, but others (particularly plots in informal settlements) are obtained by squatting or through informal market transactions. In rural areas, large commercial operations are usually concessions granted by the state under formal law, but small holdings and village and communal lands tend to be governed by customary law (Leisz 1998; Adams and Palmer 2007; Vlassenroot and Huggins 2005).

At present, land tenure information is unavailable for much of the country. In the eastern provinces that have been the subject of some limited studies (largely because they have been the center of much of the country’s violence) rural land rights are characterized as insecure. The Congo has a 200-year history of significant migration, with people moving for employment, to take advantage of natural resources, and to escape outbreaks of violence. In many cases, the migrant groups never integrated into the new communities and never obtained secure rights to land, while their ties to their ancestral land grew more tenuous in their absence. In other cases, such as in the Kivu provinces, immigrants with ethnic ties to the region and cash to invest in land supplanted resident communities, who were forced to seek new land. The civil war exacerbated the amount of migration and land tenure insecurity. As of January 2010, the country had an estimated 2.1 million internally displaced people (IDPs), 186,000 refugees from neighboring countries living in the DRC, and 455,000 Congolese refugees in neighboring countries. IDPs returning to land in eastern provinces often find their land occupied, and land conflicts are common. As of mid-2010, the majority of IDPs remain in camps (UNHCR 2010; IDMC 2010).

In Kinshasa’s urban and peri-urban areas, an estimated 77% percent of residents reportedly own their own plots, but only about 30% have rights recognized under formal law (which are most likely perpetual or long-term concessions). Peri-urban areas are large; Kinshasa covers almost 10,000 square kilometers, but only 600 square kilometers area within the urban perimeter. Sixty percent of Kinshasa residents share their plot with at least two households; 19% of residents share a plot with between 4 and 14 households (Mayeko n.d.; UN-Habitat 2008).

Residents of urban areas in the DRC have an established practice of urban agriculture. Poor households use their residential plots to grow maize and vegetables, primarily for household consumption. Residents also cultivate public thoroughfares, hilly areas, and basins within the urban perimeter. Peri-urban areas are often devoted to farming. Kinshasa has 40,000 market gardeners who use their land to grow cash crops such as manioc and groundnuts. Many urban market gardeners form cooperatives and sell their production in informal urban markets. They often rely on untreated wastewater for irrigation, which exposes them and their customers to health risks (Mayeko n.d.).

LEGAL FRAMEWORK

The 2005 DRC Constitution provides that the country’s natural resources are for the enjoyment of all Congolese people, and that the state is responsible for ensuring that these resources are distributed equally. The government has the authority to grant concessions to land and other resources as authorized by law (GODRC 2005; GODRC 2007).

The 1973 General Property Law (Law No. 73-021), as amended, provides for state ownership of all land, subject to rights of use granted under state concessions. The law permits customary law to govern use-rights to unallocated land in rural areas (Vlassenroot and Huggins 2005; Reynolds and Flores 2008; Leisz 1998; GODRC 2007).

Despite the nationalization of all land and the introduction of formal legislation governing land use rights, as a practical matter, a significant percentage of the land in the DRC (some estimate as much as 97%) remains subject to customary law. Traditional authorities such as chiefs continue to administer land on behalf of local communities in many areas, often in alliance with government officials. As rights have evolved and populations shifted over time, multiple layers of rights over specific areas of land and forest are common. Bantu agricultural communities recognize customary access rights to fixed territories that extend 5-10 kilometers from villages. Rights of access to other natural resources, such as game and fish, may extend further (Counsell 2006; Leisz 1998; Zongwe et al. 2009).

TENURE TYPES

Under formal law, the state owns all the land in the DRC; people and entities desiring use-rights to land can apply for concessions in perpetuity or standard concessions. Concessions in perpetuity (concessions perpétuelles) are available only to Congolese nationals and are transferable and inheritable by Congolese nationals. The state can terminate concessions in perpetuity through expropriation. The state can grant standard concessions (concessions ordinaires) to any natural person or legal entity, whether of Congolese or foreign nationality. Standard concessions are granted for specific time periods, usually up to 25 years with the possibility of renewal. Renewal is usually guaranteed so long as the land is developed and used in accordance with the terms of the concession (Musafiri 2008).

Although the formal law applies to all land in the DRC, as a practical matter, application of the DRC’s formal law relating to concessions tends to be restricted to urban areas and large holdings of productive land in rural areas. In most rural areas, customary law governs. Under customary law, groups and clans hold land collectively, and traditional leaders allocate use-rights to parcels. Rural land used for agricultural and residential purposes has become highly individualized in some areas over the years. Community members have the authority to loan, lease for cash, or sharecrop their individualized plots of communal land, but in most areas they cannot sell or permanently alienate the communal land to people outside the community. As areas have become commercialized, the prohibition against the sale of land to outsiders has relaxed (GODRC Constitution 2005; Musafiri 2008; Leisz 1998; Vlassenroot and Huggins 2005).

SECURING LAND RIGHTS

In the colonial period, the DRC followed a Torrens system in which land held by Europeans was surveyed, titled, and titles registered in centrally maintained land books. At Independence in 1960, all holders of registered land were required to re-register their land and prove that the land was put to appropriate and productive use. The percentage of land that was originally registered or re-registered is unknown, as is the extent of concessions granted by the government under the 1973 General Property Law. Concessions can be granted in the name of an individual or group of individuals. The frequency of married couples registering concessions in the names of both spouses is unknown (Leisz 1998; Coutsoukis 1993).

Most Congolese obtain land-rights through inheritance, customary land-allocations from chiefs, or concessions from government officials. Concessions are most common in urban and peri-urban areas and agricultural areas with large commercial landholdings. Customary tenure systems dominate in rural areas and in informal settlements in urban and peri-urban areas. In some areas, particularly areas affected by conflict and those where natural resources are extracted, the state government has posted local representatives who impose taxes on locals and business interests. Traditional authorities in many areas have retained their authority by forming alliances with local government officials; both chiefs and government administrators allocate land, often in exchange for political loyalty and without reference to requirements of the formal law. Particularly in regions where there are inadequate numbers of government officials, chiefs may serve as local representatives, blurring the distinction between formal and customary authority. In some areas, chiefs granting land-rights are issuing a type of concession document but there are no established forms and no procedures for recording the documents (Leisz 1998; Coutsoukis 1993; Vlassenroot and Romkema 2007; Vlassenroot and Huggins 2005).

Since Independence successive governments have both granted and denied foreigners the right to be treated as nationals for purposes of obtaining land-rights. Most recently, in an effort to address tensions over land claims asserted by immigrants from Rwanda who have ties to the land in the eastern provinces, the government defined Congolese nationals as those descending from a tribe that can trace its roots to the DRC to a time period before 1885. With support of the chiefs, government administrators in some areas (especially the eastern provinces) evicted occupants of communal land and plantations and sold the land to a growing class of rural elite, including large numbers of immigrants from Rwanda. The formal law does not recognize private land-ownership, (only perpetual or standard concessions), and the legal status of the rights obtained through these land transfers is ambiguous (Vlassenroot and Huggins 2005; Reynolds and Flores 2008; Leisz 1998).

Chiefs continue to grant rights to forestland for hunting and gathering in many areas, and community members may obtain rights to forest through clearing the land for agriculture. By some reports, in some areas where communities are structured on a principle of reciprocity and the exchange of social capital as opposed to ethnicity or lineage, newcomers may be able to integrate into communities and obtain individualized land-allocations available to community members; those who do not integrate into a community can often rent land from community members for cash. However, in other areas chiefs and other traditional authorities may preserve homogeneity in their control over land and deny people access to land based on their ethnicity, lineage, or gender (Leisz 1998; Musafiri 2008; Vlassenroot and Huggins 2005; WCS 2003).

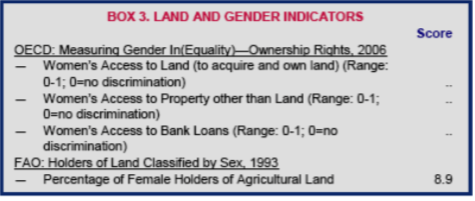

INTRA-HOUSEHOLD RIGHTS TO LAND AND GENDER DIFFERENCES

The DRC’s Constitution provides for equality of women and prohibits discrimination on the basis of sex. However, many of the country’s formal laws continue to discriminate against women. A married woman must obtain her husband’s permission to purchase or lease land, to open a bank account, and to accept a job. Husbands have a right to their wives’ property, even if the couple enters into a contract to the contrary. Women and girls have low literacy rates (55%, compared to 76% men) and sexual violence against women and girls is high. Women’s access to justice is limited by their lack of education, financial resources, information, and assistance (UN-CEDAW 2006; Zongwe et al. 2009; USDOS 2009b; FAO 1995).

The DRC’s Constitution provides for equality of women and prohibits discrimination on the basis of sex. However, many of the country’s formal laws continue to discriminate against women. A married woman must obtain her husband’s permission to purchase or lease land, to open a bank account, and to accept a job. Husbands have a right to their wives’ property, even if the couple enters into a contract to the contrary. Women and girls have low literacy rates (55%, compared to 76% men) and sexual violence against women and girls is high. Women’s access to justice is limited by their lack of education, financial resources, information, and assistance (UN-CEDAW 2006; Zongwe et al. 2009; USDOS 2009b; FAO 1995).

Ninety-five percent of rural women work in agriculture and dominate agricultural production in the DRC. Women represent 60% of agricultural laborers and 73% of farmers, and produce 80% of food crops for household consumption. Roughly 25% of all land in the DRC is considered to be held by women, with the majority of those landholders being single, widowed and divorced (FAO 2005; Phuna n.d.).

Although matrilineal systems dominate in some parts of the country, in general the majority of women in the DRC only have use-rights to land and access land through their husbands or a chief. Upon marriage a presumption exists that husbands will provide wives with sufficient land for cultivation for the family’s consumption. Women often have decision-making authority over the cultivation of the land allotted to them and the right to the harvest from the land, but they are not considered owners of the land. In most areas, ultimate authority over the land remains with male family members (FAO 1995; Leisz 1998).

Many women farmers in the DRC are organized into groups and are increasingly vocal about issues of personal security and food security. In 2009, 28 women’s groups from North Kivu Province brought their concerns to the Minister of Agriculture, asking for support against militias preventing the women’s access to farmland, help with inputs, and access to agricultural extension services (AA-DRC 2009).

LAND ADMINISTRATION AND INSTITUTIONS

The Ministry of Land Affairs has overall responsibility for the country’s urban and rural land and land administration. Within the ministry, various departments are assigned to handle registration, surveys, management of state land concessions (including allocation of concessions), and provide a land-dispute service. The extent to which the Ministry of Land Affairs and its various departments are functioning is unknown (Vlassenroot and Huggins 2005; Zongwe et al. 2009; Leisz 1998).

The Ministry of Agriculture is responsible for the functioning of the agricultural sector and provision of agricultural services. The ministry’s priorities are to: revitalize the sector through strengthening of capacity within the ministry and sector; rehabilitate basic infrastructure; support commercialization and productive investment; protect environmental resources; and promote development and strengthening of rural organizations (GODRC 2003).

LAND MARKETS AND INVESTMENTS

Despite the DRC’s large land mass and relatively low population density, accessible agricultural land and land in areas near urban markets is increasingly scarce. The formal law provides extensive procedures for obtaining concessions, beginning with an application to the provincial governor. The governor authorizes the district commissioner to arrange for a land survey that involves visual inspection, local interviews, and a determination of existing uses. When the survey is complete, the application is sent to the governor who forwards it to the Minister. Final approval is granted by officials at district, provincial, or central levels based on the amount of land involved. It is unknown how often the process is followed and the extent to which concessions are freely transferable (Leisz 1998; Vlassenroot and Huggins 2005).

- Under customary law applicable in most parts of the DRC, land may be leased to third parties for cash or a share of the production, but sales of land are generally prohibited. In some areas, however, especially rural areas in eastern provinces and urban areas, an informal land sale market exists. Traditional authorities have sold rights to communal land to rural elites and commercial interests, and rights to urban plots are sold informally. Banyarwanda immigrants from Rwanda who were denied land by tribal authorities purchased land from local government administrators (UN-Habitat 2008; Vlassenroot and Higgins 2005; Leisz 199819981998).

COMPULSORY ACQUISITION OF PRIVATE PROPERTY RIGHTS BY GOVERNMENT

Under the Constitution and the DRC’s 1977 Expropriation Law (Law No. 77-001), the state owns all land in the DRC and can expropriate land under concession and held by local communities as it deems necessary for public use or in the public interest, subject to payment of compensation. The expropriation process begins with a survey and valuation, followed by issuance of an order signed by the Minister of Land Affairs or a presidential decree (for expropriation of entire zones) identifying the land for expropriation and notifying the concession-holder. Concession-holders have one month to submit any objections and make a specific request for payment of compensation. If the parties do not agree on the amount of compensation, the law provides that the court will make the determination (GODRC Constitution 2005; Vlassenroot and Huggins 2005; Musafiri 2008).

The state has used its power of expropriation to evict indigenous communities from forestland, such as in the case of the removal of 3,000-6,000 Batwa families from the Kahuzi-Biega forest in the 1970s. The expropriation took place without notice and without payment of compensation to the families who lost their land. The current frequency and nature of government land expropriations, and the extent to which the government abides by the legislated procedures, is unknown (Musafiri 2008).

LAND DISPUTES AND CONFLICTS

Control over the DRC’s land and natural resources has been a cause of and a means to perpetuate violent conflict. With the support of the Multi-Country Demobilization and Reintegration Program (MDRP) for the Great Lakes Region of Africa and the UN Peacekeeping Mission in the DRC, the DRC’s Disarmament, Demobilization, Repatriation, Reintegration and Resettlement (DDRRR) program disarmed and demobilized thousands of ex-combatants since 2002. Armed clashes between groups continue however, especially in the eastern region; some observers suggest that the government and donors have lacked the coordinated policy, strategy and institutional arrangements necessary to attack the presence of armed combatants comprehensively and effectively for any meaningful period of time. Rebel groups have used natural resources and land access to fund conflict and have seized and distributed land to members. Smallholders and marginalized groups fleeing violence encroach on land used by others. Residents who return often find their land occupied. Disputes erupt as a result of widespread displacement during years of conflict, lack of known, enforceable principles governing land tenure, lack of land records, land-grabbing, and corruption in the exercise of land-allocation by local officials and traditional leaders (Huggins 2004; Adams and Palmer 2007; GODRC 2007; UNHCR 2010; IDMC 2010; IRIN 2010; Romkema 2007).

The DRC’s formal court system has jurisdiction over land issues, but the system is in disarray. The courts lack financial resources, suffer interference from political and military leaders, and lack basic skills and training. Allegations of corruption and mismanagement are common. One reported cause of a violent conflict between the Hema and the Lendu ethnic groups in Ituri Province in northeastern DRC was alleged bribery of the judges adjudicating a land dispute. Lack of confidence in the formal judicial system leads many to take claims to the police, military, or traditional dispute resolution systems. The authority of the customary system of dispute resolution has weakened in some areas where communities view traditional rulers as biased and self-interested. In addition, traditional forums are often unable to address the complexity of land issues in the post-conflict environment (Global Witness 2007; Vlassenroot and Huggins 2004; Vlassenroot and Huggins 2005; HRW 2004).

KEY LAND ISSUES AND GOVERNMENT INTERVENTIONS

The DRC established a 5-year (2007-2012) National Development Plan for reconstruction and development of the country, consistent with its 2006 Poverty Reduction Strategy Paper (PRSP). The Programme includes support for modernization of cropping methods and restoration of diversified cash crops, revitalization of the livestock sector, and support for producers through the distribution of inputs, dissemination of applied research, creation of cooperatives, and the development and organization of agricultural markets (USDOS 2009a; USDOS 2009b; World Bank 2010a).

The government’s 8-year rehabilitation and recovery project, which ended in 2010, exceeded its goals in the agricultural sector, providing about 2.1 million households with improved seeds and other inputs and repairing 2000 kilometers of feeder roads. In March 2010, the DRC initiated its follow-on Agriculture Rehabilitation and Recovery Support Project, which is supported with a 5-year (2010-2015) US $130 million International Development Assistance (IDA) grant. The project aims to increase agricultural productivity and improve marketing of crops and animal products by smallholder farmers in targeted areas, specifically 105,000 farming households in northwestern and north-central provinces. The project includes components dedicated to improvement of agricultural and animal production, marketing infrastructure improvement, development of farming associations, and capacity-building support to the Ministry of Agriculture, the Ministry of Rural Development, and project management. In June 2010, the DRC joined Burundi, Uganda, Malawi, Rwanda, Swaziland, and Ethiopia in the launch of the Comprehensive Africa Agricultural Development Program (CAADP), with the goal of restoring its agricultural sector. The government is in the process of creating the strategies and programs to achieve the desired 6% agricultural sector growth (World Bank 2009e; World Bank 2010b).

DONOR INTERVENTIONS

USAID’s work in the DRC is primarily designed to assist the government in transitioning to a sound democracy with a healthier population benefiting from improved livelihoods. USAID is seeking US $36.6 million in funding for its FY11 economic growth program focused on developing agricultural production and marketing, with an emphasis on food crops and particular emphasis on private firms and farmers. USAID and the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) are assisting the Ministry of Agriculture through technical support to the CAADP process, analytical support in the design of an agricultural strategy, including an agricultural growth analysis, research on key strategic issues such as investment priorities, and facilitation of policy dialogue and communication with stakeholders. These programs do not appear to have components related to land access or tenure security. USAID is also supporting the government in developing its judiciary, strengthening the rule of law, and providing vulnerable populations with access to justice. Further, USAID plans to make a $4.7 million grant to UN-Habitat in the near future to support mediation of land disputes and a process to reform land tenure laws, according to a representative from USAID/DRC in September, 2010 (USDOS 2009a; USAID 2010; USDOS 2010).

In 2009, the International Development Research Centre (IDRC) initiated a 3-year project helping the government to develop participatory mechanisms for good governance of natural resources, with a focus on encouraging the emergence and reinforcement of female leadership and promoting the rights of women and displaced households to access and use of natural resources. The international NGO Citizen’s Network for Justice and Democracy (Réseau des Citoyens pour la Justice et la Démocratie (RCN)) has supported training for the judiciary on the land laws (IDRC 2009; Adams and Palmer 2007).

USAID funded the 2-year, US $5 million Congo Livelihood Improvement and Food Security (CLIFS) Project from 2004 to 2006. The project was implemented by 14 different NGOs and was designed to improve livelihoods and food security by improving the functioning of agricultural markets, increasing the level and sustainability of agricultural production and fisheries, and strengthening rural credit. The project reported that income in two areas tripled during the project term (IRM 2006; USAID 2005).

Freshwater (Lakes, Rivers, Groundwater)

RESOURCE QUANTITY, QUALITY, USE AND DISTRIBUTION

The DRC is the wettest country on the African continent and home to one-quarter of Africa’s freshwater resources. Internal annual renewable water resources average 900 cubic kilometers. The Congo River is 4670 kilometers long and supports five major tributaries that create a dense water system with more than 20,000 kilometers of riverbank and shoreline and a catchment area of 3.7 million square kilometers. Lake Tanganyika, the second deepest lake in the world, stretches 700 kilometers along the country’s southeastern border and has a surface area of 32,893 square kilometers. Other major lakes include Lake Kivu, Lake Edward, and Lake Albert. Fifty-three percent of water withdrawn in the DRC is used for domestic purposes, 30% for agriculture, and 17% for industry (FAO 2005; World Bank 2009a; WCS 2003).

The DRC’s extensive water resources are largely untapped. The Inga Dam on the Congo River in western DRC has between 40,000-45,000 megawatts of hydropower potential (compared to 14,000 megawatts produced by the highest-ranked hydroelectric plant at the Itaipu Dam in Paraguay/Brazil). The Inga Dam is operating at only a fraction of its capacity (1750 megawatts) because of lack of investment and functioning infrastructure. An estimated 90 to 95% of households do not have electricity (World Bank 2009d).

Only 40% of the urban population and 9% of the rural population have access to sanitation facilities. The DRC’s water suffers from pollution from cities, industrial activity, and the oil industry along the Atlantic coast. Twenty-two percent of the country’s population has access to safe drinking water (compared to an average of roughly 60% in sub-Saharan Africa). Eighty percent of disease in the DRC (cholera, typhoid fever, hepatitis A and bacterial and protozoan diarrhea) and one-third of deaths are related to contaminated water (FAO 2005; Boinet and Mondain 2009).

LEGAL FRAMEWORK

The Constitution provides that the state owns all of the natural resources, including water. The government has been working on a comprehensive water law for several years (GODRC Constitution 2005; FAO 2005; WWF 2009).

TENURE ISSUES

The DRC does not have a formal water law. Various draft water laws have included objectives to conserve common resources, reconcile different uses, prevent pollution and harmful effects from floods, treat water as an economic resource, and prevent overexploitation. The 2002 Mining Code (Law No. 007/2202 of 11 July) gives holders of mineral exploitation permits the right to use subsurface water resources within the extent of land or perimeter granted (FAO 2005; WWF 2009; GODRC Mining Code 2002).

Under customary law, land rights include use-rights to surface and groundwater (FAO 2005; WWF 2009).

GOVERNMENT ADMINISTRATION AND INSTITUTIONS

Responsibility for water resources and water management in the DRC is fragmented among at least seven different ministries, coordinated by the National Action Committee on Water and Sanitation (Comité National d’Action de l’Eau et de l’Assainissement (CNAEA)). The primary ministries exercising authority over water resources are the Ministry of Energy, Ministry of Agriculture, Ministry of Rural Development, and Ministry of the Environment, Nature Conservation, and Tourism (Regideso 2008; FAO 2005; World Bank 2009b).

The Ministry of Energy oversees Régie de distribution d’eau (Regideso), the DRC’s autonomous public water utility, which is charged with responsibility for the production and distribution of water to primarily urban residential, commercial, and industrial customers. The utility’s operational performance and financial situation worsened over the years of conflict as distribution networks and production systems were destroyed or became obsolete. The state has not paid its water bills and the revenue Regideso collects from declining numbers of customers does not cover its operating costs. The Ministry of Agriculture and Ministry of Rural Development manage the rural water supply, and the Ministry of the Environment, Nature Conservation and Tourism has responsibility for managing water ecosystems. The jurisdictions of the ministries often overlap and ambiguity over areas of responsibility is common. The ministries also lack financial resources, equipment and technical tools, and technical capacity (Regideso 2008; WWF 2009; FAO 2005; World Bank 2009b).

GOVERNMENT REFORMS, INTERVENTIONS AND INVESTMENTS

The government recognizes that inadequacies within the legal and institutional framework are an obstacle to reform of the water sector. Lack of coordination and competition among different organizations has led to three different draft water laws, gaps in sector activity areas, and overlapping competencies. With the support of the German Agency for Technical Cooperation (GTZ), the government is developing a plan for water-sector reform, including creating a water policy and a plan for restructuring the relevant institutions (GTZ 2009c).

With the support of the World Bank, the Congolese government launched its Urban Water Supply Project (Project d’Alimentation en Eau Potable en Milieu Urbain (PEMU)), which is designed to provide safe drinking water to the country’s urban areas. The project plans to reestablish Regideso’s financial viability, reforming oversight of the sector and turning it into a commercial enterprise, enlisting the services of a specialized professional operator for five years, and repairing and modernizing facilities (World Bank 2009b).

The DRC, Cameroon, Republic of the Congo, and Central African Republic ratified an accord in 2003 to establish the International Commission of the Congo-Oubangui-Sangha Basin (CICOS). The Commission is the first step in an effort to coordinate use and protection of the shared water basin resources and strengthen cooperation in the areas of shipping and water pollution control (GTZ 2009b).

DONOR INTERVENTIONS AND INVESTMENTS

The World Bank is supporting the GODRC’s 6-year (2008-2014) US $190 million project to provide safe drinking water in three of its largest urban areas: Kinshasa, Matadi, and Lubumbashi. As of late 2009, the project had restored 84 water points, built a new water treatment plant, and provided about 3 million Kinshasa residents with access to safe water. The African Development Bank is financing a US $100 million government project to provide safe water to small towns, targeting socially disadvantaged populations (Boinet and Mondain 2009; World Bank 2009e).

The World Bank has provided US $1 million in funding through the Southern African Power Market Project (SAPMP) and the Regional and Domestic Power Markets Development Project (PMEDE) to help the government improve the two existing power plants in the Inga Dam complex. Several members of the Southern African Development Community (SADC), including South Africa, Namibia, Angola, and Botswana, have formed the Westcor Power Project to support the construction of a third power plant that would provide electricity to all five countries. Civil society members have criticized the project as focused on the sale of energy to other countries and the mining and industrial sectors of the country as opposed to the population of the DRC (World Bank 2009d; Geni 2009).

GTZ is funding a 9-year (2006-2013) project supporting transborder water management in the Congo Basin. The goal of the project is to ensure that coordination of river-basin management among countries of the Congo River Basin takes places according to coordinated principles and strategies (GTZ 2009b).

Trees and Forests

RESOURCE QUANTITY, QUALITY, USE AND DISTRIBUTION

The DRC’s primeval forest is the largest uninterrupted tropical forest area in Africa and is the second-largest tropical rainforest in the world (after the Amazon). The forest covers 222 million square kilometers, about half of which are closed high rainforests and half are woody savanna and open forest. The DRC’s forests are one of the world’s most biodiverse areas, home to an estimated 10,000 species of plants, 409 species of mammals, 1117 bird species, and 400 species of fish. The DRC’s forests are critical to the livelihoods of at least 40 million people, providing game, food and medicinal plants, and fuelwood that supplies 80% of the country’s energy needs (FAO 2005; Counsell 2006; Atyi and Bayol 2008; CBFP 2006).

The DRC’s forests are under pressure from exploitation for fuelwood and timber, slash-and-burn cultivation techniques, development of palm oil plantations, and the expansion of urban areas. In the timber industry, corruption has been commonplace: companies and individuals have made cash or in-kind payments to government and military officials in exchange for illegal logging permits and assistance facilitating smuggling and illegal exports. People living in and near forests often encroach on protected areas in order to grow food and obtain fuelwood and game to sustain their families. In the late 1990’s, the government began updating the legal framework and particularly in the period since 2007 has been adopting new initiatives and establishing governance bodies to address past weaknesses in enforcement and administration (FAO 2009a; Global Witness 2007; Atyi and Bayol 2008; CBFP 2006).

In addition to other forest users, an estimated 400,000 to 600,000 indigenous communities of Bacwa, Bambuti, and Batwa hunter-gatherers, known as pygmies, live in the DRC and are considered the country’s earliest occupants. Other ethnic groups, including the Bantu, Nilotes, and Sudanese, followed by colonialists, migrated into the region, often displacing the pygmies. The pygmies have territories where access rights are based on family lineage and social groupings and may be shared among lineages and community groups. Areas for gathering and hunting tend to be extensive and overlap with other uses and users. Pygmies may shift base camps 4-6 times a year, and rights of access shift with the changes in location. There is often little physical evidence of pygmy forest areas, and officials and others may intentionally or unintentionally grant concessions to others for the land, or clear it for cultivation without consulting or compensating the pygmies (Musafiri 2008; Counsell 2006).

The DRC’s forests have been described as the earth’s “second lung” because of their ability to store carbon. The DRC’s rate of deforestation is relatively low (between 0.2-0.3% per year in 2008), but because of the size and diversity of its forests, even a relatively small rate of annual deforestation places the DRC in the top ten sites of tropical forest deforestation in the world. The DRC is a participant in the United Nations Collaborative Programme on Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation in Developing Countries (UN-REDD Programme) and has developed a national REDD/REDD+ Readiness Plan under the World Bank Forest Carbon Partnership Facility, with the objectives to maintain the forest carbon pool and reduce future deforestation rates (GODRC 2010; UN-REDD 2009; UN-REDD 2010; Atyi and Bayol 2008).

LEGAL FRAMEWORK

The DRC enacted a new Forest Code in 2002, replacing the Forest Law of 11 April 1949. Consistent with the 1973 General Property Law, the Code provides that the state owns all forestland and is responsible for managing the forest resources. The Code creates categories of forestland for exploitation, conservation, and community use and allows for concessions for timber harvesting. The Code includes a list of forest management objectives, including industrial timber production, nature conservation, and community use. An estimated 42 decrees and regulations were identified as necessary to ensure implementation of the Forest Code. While progress toward enacting the necessary legislation was initially slow, as of December 2009, at least 31 decrees or regulations (arêtes) had been adopted and the remaining regulations were in process. The Ministry of Environment, Nature Conservation and Tourism (MECNT) has also drafted operational guidelines establishing technical standards for forest management work, such as inventories and mapping. The government supported its progress on implementing the Forest Code with support for independent monitoring and restoration of basic enforcement capacity in the field and establishment of a national steering committee (Comité National de Pilotage du Zonage Forestier) to oversee the zoning of its forests (Sidle 2010; Atyi and Bayol 2008).

The DRC’s national forest management policy, as expressed in the 1990 Tropical Forests Management Plan, articulates objectives of promoting forest harvesting on a sustainable basis and supporting forest industries to enhance the forest sector’s contribution to the DRC’s socioeconomic development. The policy includes establishment of fuelwood plantations, the development of ecotourism, and involvement of local people in conservation and management of protected areas (FAO 2009a).

TENURE TYPES AND SECURITY

The 2002 Forest Code recognizes three categories of forest: (1) classified forests, which are generally those forests designated for environmental protection and have restrictions on use and exploitation (e.g., nature reserves, national parks); (2) protected forests, which are subject to less stringent restrictions than classified forests (e.g., community forests, limited concessions); and (3) permanent production forests, which include forests that are already used for timber production and under long term concessions. Local people may use protected forests for subsistence needs and may clear the forest for crops; a permit is required to clear a forest area larger than two hectares (Atyi and Bayol 2008).

The DRC’s 2002 Forest Code allows for two types of forest harvesting concessions: simple felling permits for small-scale logging with cross-cut saws, and large-scale industrial logging permits. Permits are subject to allowable annual cut limits, which are imposed by species and by area. Permits are required for harvesting non-timber or minor forest products. The maximum concession size is 400,000 hectares. A logging company must provide a harvesting inventory before applying for felling permits. Felling permits are issued for areas up to 1000 hectares, and logging companies can obtain as many permits as the state deems consistent with forest capacity. Permit holders must submit quarterly reports of volumes felled and must comply with the DRC’s Guide to Forest Exploitation. A three-year moratorium on the allocation of new logging concessions was announced in October 2008 (FAO 2009a; Counsell 2006; Atyi and Bayol 2008).

The DRC’s oversight of concessions and Forest Code requirements has been poor, and the significant amount of corruption in the sector led members of civil society to call for review of all concessions. Responding to pressure from international donors, in 2004 the DRC placed a moratorium on the issuance of new logging concessions and sought an independent review of the process of reviewing the legality of the 156 existing concessions. The process resulted in the cancellation of 91 concessions, and an inter-ministerial commission declared 65 concessions were convertible under the standards imposed by the 2002 Forest Code. The process, which independent observers attested was in full compliance with applicable law, reduced the amount of forest under concession from an estimated 22 million hectares to about 10 million hectares. The DRC annually exports 500,000 cubic meters of timber; FAO estimates that at least twice that amount is unofficially exported (FAO 2009a; Illegal Logging 2010; Counsell 2006; Greenpeace 2010; Forest Monitor 2007; Methot and Thompson 2009).

The 2002 Forest Code recognizes indigenous use-rights to forests but does not delineate use rights or processes for certifying and managing community forests. As of December 2009, several regulations addressing community forest rights were under development. In 2007, a group of indigenous peoples organizations submitted a formal report to the international Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination, alleging: (1) violation of Indigenous Peoples’ rights to lands, territories, and resources; (2) violation of the principle of free prior and informed consent; and (3) threats to the integrity and security of pygmies resulting from the lack of enforcement of the 2002 moratorium on logging concessions. The government developed a Consultation Protocol to ensure recognition of the rights of local communities and indigenous peoples in its review of logging concessions and imposed new social obligations on the reformed concessions. The DRC’s REDD+ strategy proposal submitted to UN-REDD and the Forest Carbon Partnership Facility (FCPF) include substantial attention to the meaningful participation of local forest-dependent communities and indigenous peoples in the design, development, and implementation of REDD+ projects (Musafiri 2008; Counsell 2006; UN-REDD 2009; Methot and Thompson; GODRC 2010; IDA 2007).

GOVERNMENT ADMINISTRATION AND INSTITUTIONS

The Ministry of the Environment, Nature Conservation, and Tourism (MECNT) is responsible for the forest sector, including environmental protection, the conservation of nature, and forest harvesting. The Directorate of Forest Management and Game has authority over forest harvesting and hunting. The Directorate of Permanent Forest Inventory Management (Direction Permanent d’Inventaire de d’Amenagement Forestiers (DPIAF)) handles forest management plans, forest inventories, and research and development. The Directorate of Natural Resource Management is responsible for the normative aspects of forest management and resource allocation, and the Congolese Institute for Nature Conservation (ICCN) is responsible for managing protected areas and environmental conservation. The DRC’s National Reforestation Department (SNR) is in charge of reforestation work. The National Centre for Environmental Information (CNIE) is responsible for environmental data collection, and the Permanent Secretariat of the Inter-Ministerial Committee on the Environment is responsible for coordination with environmentally linked work in other ministries (FAO 2009a; Musafiri 2008).

The DRC has recognized that governance of the forest sector has suffered from lack of capacity, mismanagement, turnover in high-level personnel, and corruption. Many of the progressive components of the 2002 Forest Code, including community forest management, lacked implementing regulations in the years following enactment of the Code. However, with the help of donors, the DRC has begun to address weaknesses in forest administration, including undertaking capacity building within the MECNT (IDA 2007; Sidle 2010; CIFOR et al. 2007; ARD 2003; Counsell 2006).

GOVERNMENT REFORMS, INTERVENTIONS AND INVESTMENTS

The DRC has been devoting attention to the forestry sector in recent years, strengthening the legal framework with implementing regulations and decrees and forming new governance bodies to address gaps in information and past mismanagement of resources. The DRC successfully cancelled illegal logging concessions, reformed others to meet more stringent requirements, and imposed a new moratorium on new concessions. With support from USAID/CARPE and the US Forest Service, the DRC created an inter-ministerial commission for land use planning, drafted a forest land use planning guide, and is actively working to create a process to allocate forest use according to the forest code and participatory principals of local authorities and communities (Methot and Thompson 2009; Sidle 2010; IDA 2007).

Supported by the UN-REDD and with an initial grant from the Forest Carbon Partnership Facility, the DRC began implementing its national REDD readiness program in 2008. Civil society members, including representatives from Forestry Working Group (Groupe de Travail Forestier), LINAPYCO (the National League of the Indigenous Pygmy Organization in the Congo), Dynamic Indigenous People (Dynamique Peuple Autochtone), and Natural Resources Network (Réseau Ressources Naturelles), established a Climate-REDD working group that is collaborating with the government, donors, and international donors. The DRC submitted its Readiness Plan for REDD (2010–2012) in July 2010. The Plan focuses on: (1) building the government’s capacity to guide and control the country’s transformation toward REDD, including establishing institutions and a credible governance system; (2) decentralizing the national REDD strategy by providing tools and guidance, and monitoring the strategic planning efforts at the provincial level; (3) making those players most likely to develop and control forest lands more aware of their responsibilities for emissions reductions; (4) building diplomatic capacities; (5) mobilizing international funders to support an ambitious program by securing credibility, effectiveness, and good governance conditions; and (6) involving the country in a deep transformation toward a global system where all stakeholders are engaged in forest preservation. An example of a carbon forestry project is the Ibi Bateke Carbon Sink Plantation project, which will promote the afforestation of 4220 hectares on the Bateke Plateau, contributing to the supply of fuelwood to Kinshasa while also creating a carbon sink capable of sequestering an estimated 2.4 million of tons of CO2 over 30 years. The project is scheduled to begin in 2010 and will be implemented by NOVACEL (Nouvelle Société d’Agriculture, Culture et Élevage), a private local company (UN-REDD 2010; UN-REDD 2009; World Bank 2009f; GODRC 2009).

The DRC is a member of the Central African Forest Commission (COMIFAC), which is made up of the forestry ministers of participating Central African countries and is the primary authority for decision-making and coordination of sub-regional actions and initiatives focused on conservation and sustainable management of the Congo Basin forests. COMIFAC is governed by the Yaounde Declaration, which recognizes the protection of the Congo Basin’s ecosystems as an integral component of the development process and reaffirms the signatories’ commitments to work cooperatively to promote the sustainable use of the Congo ecosystem in accordance with their social, economic, and environmental agendas. COMIFAC meets regularly to discuss its agenda and develop an official Convergence Plan (Plan de Convergence), an action plan that identifies COMIFAC priorities. COMIFAC’s Plan de Convergence (2003-2010) identifies major themes as: harmonization of forest policy and taxation; inventory of flora and fauna; ecosystem management; conservation of biodiversity; sustainable use of natural resources; capacity-building and community participation; research; and innovative financing mechanisms (COMIFAC 2010).

DONOR INTERVENTIONS AND INVESTMENTS

The DRC is a member of the Congo Basin Forest Partnership (CBFP), an international effort by some 45 international partners to conserve the forests and biodiversity of the Central Africa region. The Central African Regional Program for the Environment (CARPE) is the USAID-funded initiative and the principal USG mechanism to support the CBFP. CARPE aims to promote sustainable natural resource management in the Congo Basin. CARPE, a separate USAID Central Africa operating unit based in the USAID DRC Mission, funds projects designed to reduce deforestation and loss of biodiversity in ten central African countries by supporting development of local, national, and regional capacity in 12 critical landscapes. Six of those landscapes are in the DRC: (1) Lac Tele-Lac Tumba, which is a transboundary area on the western border with the Republic of Congo (Brazzaville); (2) Maringa-Lopori-Wamba (north-central region); (3) Salonga-Lukenie-Sankuru (central region); (4) Ituri-Epulu-Aru in the northeast; (5) Maiku-Tayna-Kahuzi-Biega in the northeast, including the Tayna Gorilla Reserve; and (6) Virunga, a transboundary area on the eastern border with Rwanda. CARPE is currently in the second of a planned three-phase, 20-year effort to support international and national partners to manage natural resources sustainably, strengthen natural resource governance, and institutionalize natural resource monitoring (IUCN and CARPE n.d.; CARPE 2010).

The World Bank, FAO, and the World Wildlife Fund have been working with the government to provide technical assistance on forest policy and the development and implementation of the Forest Code. The FAO has been funding dozens of diverse projects relating to the forests in the DRC, including projects focused on sustainable forest use, fisheries, food security, and technical assistance for forest management plans and strategies. The World Bank is funding a 5-year (2010-2015) US $70 million Forest and Nature Conservation Project designed to increase the capacity of the Ministry of Environment, Nature Conservation and Tourism (MECNT) and the Congolese Nature Conservation Institute (ICCN), and increase collaboration among government institutions, civil society, and other stakeholders in order to manage forests sustainably and equitably for multiple uses in pilot provinces. The project includes components to improve the institutional capacity of MECNT’s provincial offices, increase local community and civil society participation in forest management, and provide support for management of protected areas to help rehabilitate the Maiko National Park. The World Bank is also supporting the implementation of a Multi Donor Trust Fund for Forest Governance, financed by Belgium, the European Union, France, Germany, Luxembourg and the Netherlands, and a Global Environmental Facility (GEF) project for capacity-building of the ICCN and the rehabilitation of the Garamba and Virunga National Parks (Counsell 2006; FAO 2009b; World Bank 2009c; World Bank 2009e; World Bank 2009g).

GTZ is funding a 9-year (2005-2013) biodiversity and forest management project, implemented by MECNT. The project provides the central government with scientific and organizational advisory services focused on enhancing the institutional ability to preserve the forest and its biodiversity (GTZ 2009a).

Greenpeace has been an active investigator of logging practices and advocator for transparency in procedures and development of new (REDD/REDD+) mechanisms to protect biodiversity and support local communities. Local civil society groups engaged in advocacy, awareness-building, and forest management and conservation projects include the Network of Partners for the Congo Environment (Reseau des Partenaires pour l’Environnement au Congo), the Forestry Working Group (Groupe de Travail Forets), and the Natural Resources Network (Reseau Ressources Naturelles). In 2009, the NGO Forest Monitor began an 18-month project in Bas-Congo, Ituri, and Equateur to investigate local land and forest resource use to help the government design its community forestry program (CIFOR et al. 2007; Greenpeace 2008; Forest Monitor 2009).

Minerals

RESOURCE QUANTITY, QUALITY, USE AND DISTRIBUTION

The DRC has substantial mineral reserves, including what are believed to be the world’s largest reserves of cobalt and copper. Mining accounted for an estimated 13% of GDP in 2008, and the country was responsible for 45% of the world’s cobalt production, 30% of the world’s production of industrial diamonds, a 6% share of gem-quality diamond production, and 2% of the world’s copper production. The country also has significant deposits of tungsten, zinc, silver, gold, and petroleum. While the actual extent of cobalt and copper reserves is unknown, output of the two minerals is expected to increase substantially in the coming years. A new aluminum smelter is planned for Bas-Congo Province, assuming the development of the proposed Inga 3 hydroelectric power station (Yager 2010; Andre-Dumont and Cabonez 2009).

The DRC’s mineral exports were estimated at about US $6.6 billion in 2008. Cobalt accounted for 38% of total mineral exports (valued at US $2.4 billion), followed by copper (35%, US $2.3 billion), crude petroleum (12%, US $760 million), and diamonds (11%, US $540 million). Other mineral exports included gold, niobium, tantalum, tin, tourmaline, and tungsten. Copper production increased from 16,000 tons in 2003 to 335,000 tons in 2008. Cobalt production increased from 8,000 tons in 2003 to 42,000 tons in 2008. In contrast, artisanal diamond production fell from about 27 million carats in 2003 to 21 million carats in 2008. The decline is attributed to the worldwide economic crisis that led many traders to shut down operations, lack of access to capital and mining skills, the absence of cooperatives, and poor working conditions (IMF 2010; Yager 2010).

Large state and privately owned companies produce most of the country’s cobalt and copper. Small-scale and artisanal miners produce most of the country’s gold, tin, and tungsten and play a role in cobalt production. Artisanal miners were responsible for 70% of the country’s diamond production in 2009. An estimated 10 million Congolese are directly or indirectly dependent on small-scale and artisanal mining for their livelihoods. No uniform national standards and safeguards governing health and safety and good environmental practices are applied to small-scale and artisanal operations, and the miners are vulnerable to exploitation by government officials and military forces (Yager 2010;World Bank 2008a; Global Witness 2007; Pact 2009; RWI 2009; Business Monitor 2010).

The mining sector was the engine of the DRC’s economy for years, but revenues and other benefit streams were often poorly managed or diverted by elites and military and rebel forces. During the period of civil war and conflict, industrial mining declined, and informal and artisanal mining expanded and became controlled by militias and the formal military in some areas. For example, the Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda (Forces Democratiques pour la Liberation de Rwanda (FDLR)) obtained about 75% of its revenue from artisanal gold mining, and the 85th Brigade, which was not integrated into the Congolese military forces, controlled the Bisie cassiterite mines in North Kivu Province and obtained an estimated 95% of its revenue from illegal taxation and trade in minerals (World Bank 2008a; EITI 2010; Yager 2010). The majority of the DRC’s mining operations have been in the central and southeastern region (formerly Katanga and Kasai provinces), and the environment surrounding the mines has high levels of water and soil pollution. Hazardous waste has been discharged into rivers and lakes, and high levels of mercury and uranium radiation have been found in factory tailings. The levels of lead, cadmium, zinc, and copper in soil and water samples taken in Katanga Province in 2003 were two to ten times higher than internationally accepted norms (WCS 2003).

LEGAL FRAMEWORK

The 2002 Mining Code (Law No. 007/2202 of 11 July) and Mining Regulations, enacted by Decree No. 038/2003 of 26 March 2003, provide that all mineral substances, including artificial deposits, are the exclusive property of the state. The Mining Code and Regulations govern the prospecting, exploration, exploitation, processing, transportation, and sale of mineral substances, and extend to the artisanal exploitation and sale of minerals. The sections of the Mining Code and Regulations that provide for the establishment of artisanal mining zones have yet to be implemented, and the potential for conflict between artisans operating in concession areas that industrial companies wish to develop (and for which they hold the mineral rights) is high (GODRC 2002; World Bank 2008a; Global Witness 2007; Pact 2009).

The DRC is a signatory of the 2003 Kimberly Process, which established a certification system for diamonds that is designed to reduce the trade in conflict diamonds. The Kimberly Process applies to both rough and cut diamonds, and requires participating governments to ensure that each shipment of rough diamonds be exported/imported in a secure container, accompanied by a uniquely numbered, government-validated certificate stating that the diamonds are from sources free of conflict. In general, the DRC’s compliance with the Kimberly Process has been low: most of the artisanal miners and small traders in diamonds are unregistered and unregulated, and recordkeeping is poor to nonexistent. Diamonds pass from miners to mine-site buyers to larger buyers in town without government knowledge or oversight; the government has inadequate information to monitor diamond exports (Global Witness and PAC2008; Kimberly Process 2002; Yager 2008).

TENURE TYPES AND SECURITY

Under the Mining Code, rights to mineral deposits are separate and distinct from rights to land, and holders of surface rights cannot claim ownership of mineral deposits. Holders of mining or quarry exploitation rights acquire the ownership of the products for sale (GODRC 2002; Andre-Dumont and Cabonez 2009).

The Mining Code and Regulations allow those persons or entities with mining and quarry rights issued in accordance with the Code to engage in exploration and exploitation of mineral substances. Rights are granted for established perimeters, which are demarcated surface areas with indefinite depth, composed of quadrangles or squares that are registered in the chronological order of their filing. Holders of mineral exploitation rights obtain the right to occupy the land necessary for mining activities, to use the underground water, dig canals and channels, and establish means of communication on the land. Licenses for exploration are granted for four years (precious stones) and five years (other minerals); exploration licenses are generally renewable for two additional terms. Exploration licenses are granted by perimeter, an extent of land mapped by the Ministry that cannot exceed 400 square kilometers. Companies cannot hold more than 50 exploration licenses and are limited to rights over a total of 20,000 square kilometers within the DRC. Exploitation licenses are available for mining operations for 30-year periods, with multiple 15-year renewals available. Exploitation licenses are granted for specific minerals by perimeter, with no company entitled to hold more than 50 exploitation licenses (GODRC 2002; Andre-Dumont and Cabonez 2009).

Artisanal exploitation of mineral substances is limited to those of Congolese nationality with annual artisanal miners’ cards issued by the Ministry of Mines. Artisanal mining is permitted in areas where technical and economic factors make industrial or semi-industrial exploitation of the minerals impossible but allow for artisanal mining. Artisanal mining areas are created by ministerial order, and the terms of licenses are set by the Provincial Division of Mines. Artisan miners can only sell their mining products to traders, exchange markets, trading houses, or government-approved entities. Small-scale mining is permitted where deposits of mineral substances do not allow for economically viable large-scale mining operations. Small-scale exploitation licenses are available for up to ten years, including renewals, and are granted by perimeter. The Mining Code permits a holder of an exploitation license to mortgage the right, with advance approval of the Minister (GODRC 2002).

Holders of mining and quarry rights must exercise them within six months of receipt of the right, or risk forfeiture. Exploitation permits are subject to the prior approval of an environmental impact study and an environmental management plan (EMP). Exploration operations must have an approved mitigation and rehabilitation plan backed by a financial guarantee. Small-scale exploitation permits are only subject to codes of conduct. Mining and quarry rights can be lost for failure to abide by the requirements of the Mining Code and terms of the license granted, failure to pay the surface rights fee, and failure to provide required reports (GODRC 2002; Andre-Dumont and Cabonez 2009).

GOVERNMENT ADMINISTRATION AND INSTITUTIONS