Violence in Colombia has displaced families towards informal settlements. USAID is helping the government to deliver land titles to these families and respond to their needs.

Before 9 de Agosto was a barrio, it was open land on the edge of Tierralta, a town in Colombia’s Caribbean plains. The more than 40 hectares of land belonged to a local power company, and then one night, on August 9th, it became home to 3,000 desperate people. They arrived and never left.

The invasion occurred in 2010, and Jairo Gómez was there. He was one of a multitude of victims and families displaced by the violence that had engulfed their region and pushed them out of their homes. Gómez pounded in wooden posts, hung a tarp and hammock, and braced himself for the inevitable backlash. In less than a week, the police showed up with teargas and violence to evict the families. Gómez stood his ground.

The invasion occurred in 2010, and Jairo Gómez was there. He was one of a multitude of victims and families displaced by the violence that had engulfed their region and pushed them out of their homes. Gómez pounded in wooden posts, hung a tarp and hammock, and braced himself for the inevitable backlash. In less than a week, the police showed up with teargas and violence to evict the families. Gómez stood his ground.

A City of Cambuches

“It was a city of cambuches,” Gómez says, using the local word for shelters made from plastic sheeting.

Social leaders emerged, and soon they were laying lines to create the lots for dwellings and future roads. By the end of the first year, 5,000 people lived in 9 de Agosto, which anywhere else was known as the barrio de los desplazados, or displaced people.

Social leaders emerged, and soon they were laying lines to create the lots for dwellings and future roads. By the end of the first year, 5,000 people lived in 9 de Agosto, which anywhere else was known as the barrio de los desplazados, or displaced people.

That’s how a neighborhood is born in the 21st century Colombia, as shanty towns built with plastic coverings and scrap wood and carved out of open lands along major roads or near towns. The county has grown this way over the last 20 years due to the conflict that has made Colombia home to a population of more than 6 million internally displaced people (IDP)—second only to Syria—and made Colombia the country with the highest number of IDPs and the least number of refugee camps.

In 2017, the local power company traded the land to the municipality, and local leaders set up services like electricity for some of the more than 4,000 parcels. Today, many shacks and tarps have been replaced by cinder blocks and bricks. Those who can afford it, have added zinc sheets to their roofs to protect them from the heavy tropical rains. Others remain the same as they were in 2010, plastic sheeting, wooden planks, and dirt floors, simple cambuches.

Titling the Properties

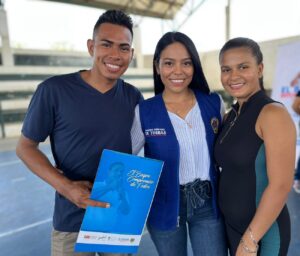

This year, with USAID support Tierralta made a giant step towards incorporating the neighborhood into the town’s masterplan by titling more than 260 parcels. The event featured Mayor Daniel Montero delivering property titles to a packed auditorium, and was significant on several levels. First, as a clear example of the government providing families with a tangible asset that will inevitably lead to improvements in their neighborhood; second, the event represents the single largest delivery of land titles made by a municipal administration in the history of Colombia. “The wait times for government services are slow and you can never get everything done, but today we have fought for something beautiful,” Montero said to the crowd. “A land title will bring you new opportunities and hopefully bring peace, happiness, and hope to your homes.”

This year, with USAID support Tierralta made a giant step towards incorporating the neighborhood into the town’s masterplan by titling more than 260 parcels. The event featured Mayor Daniel Montero delivering property titles to a packed auditorium, and was significant on several levels. First, as a clear example of the government providing families with a tangible asset that will inevitably lead to improvements in their neighborhood; second, the event represents the single largest delivery of land titles made by a municipal administration in the history of Colombia. “The wait times for government services are slow and you can never get everything done, but today we have fought for something beautiful,” Montero said to the crowd. “A land title will bring you new opportunities and hopefully bring peace, happiness, and hope to your homes.”

Local Land Administration

The Colombian government has struggled to facilitate land planning in areas affected by the conflict or to provide residents with services to legalize the properties of informal settlements like 9 de Agosto.

The Colombian government has struggled to facilitate land planning in areas affected by the conflict or to provide residents with services to legalize the properties of informal settlements like 9 de Agosto.

In 2021, USAID helped Tierralta reactivate its Municipal Land Office, which employs a team of land experts and surveyors who live in the municipality and work under the municipal Secretary of Planning. Under Colombian land law, municipalities have the power to process the titling of urban properties, including public properties like schools and health centers.

With USAID’s support, Tierralta’s Municipal Land Office has improved its capacity to title urban property and reduced processing times from multiple years to just a few months. Key to the process is the improvement in communication and work flow between land agencies, or in this case with Colombia’s property registry authority, the Superintendence of Notaries and Registers (SNR). By working directly with the regional SNR office, Tierralta’s Land Office can title dozens of properties at a time.

With USAID’s support, Tierralta’s Municipal Land Office has improved its capacity to title urban property and reduced processing times from multiple years to just a few months. Key to the process is the improvement in communication and work flow between land agencies, or in this case with Colombia’s property registry authority, the Superintendence of Notaries and Registers (SNR). By working directly with the regional SNR office, Tierralta’s Land Office can title dozens of properties at a time.

For every single property, the SNR requires a physical verification of the property as well as the property’s history. Municipal Land Offices are fulfilling these tasks.

“In municipalities with land offices supported by USAID, we see that we are delivering more titles, and our goals are achieved in a more agile and comprehensive manner.It is really important that there are professionals working in these municipalities, because this work will not be done from Bogotá. Municipal Land Offices are facilitating the cooperation between our offices,” says María José Muñoz, who works in the SNR as a Delegate for Land Protection, Restitution and Formalization.

Since 2020, 42 USAID-supported Municipal and Regional Land Offices delivered over 6,800 land titles to families living in the urban areas of rural municipalities. In addition, the land offices have formalized more than 1,600 public properties and provided land and property services to more than 16,000 citizens.

Since 2020, 42 USAID-supported Municipal and Regional Land Offices delivered over 6,800 land titles to families living in the urban areas of rural municipalities. In addition, the land offices have formalized more than 1,600 public properties and provided land and property services to more than 16,000 citizens.

Cross-posted from USAID Exposure

Theirs is one of 30 land titles delivered at an event earlier this year by Chaparral’s Municipal Land Office (MLO), which was created with support from the Land for Prosperity. The Land Office operates under the Municipality’s Secretary of Planning and is something of a one-stop shop for local land administration. It facilitates rural development initiatives and allows the local leaders to deliver on state-led land titling strategies that take the onus off land owners.

Theirs is one of 30 land titles delivered at an event earlier this year by Chaparral’s Municipal Land Office (MLO), which was created with support from the Land for Prosperity. The Land Office operates under the Municipality’s Secretary of Planning and is something of a one-stop shop for local land administration. It facilitates rural development initiatives and allows the local leaders to deliver on state-led land titling strategies that take the onus off land owners. For now, the Municipal Land Office is operating thanks to Natalia Quinoñes. As the MLO’s legal expert, she reviews hundreds of urban properties and provides citizens with information to begin to understand the complexity of Colombia’s land laws and the process of property formalization. Quiñones graduated in law last year and is relatively new to the land administration. In her job, learning is a continuous process, and she studies how land laws are evolving in today’s Colombia.

For now, the Municipal Land Office is operating thanks to Natalia Quinoñes. As the MLO’s legal expert, she reviews hundreds of urban properties and provides citizens with information to begin to understand the complexity of Colombia’s land laws and the process of property formalization. Quiñones graduated in law last year and is relatively new to the land administration. In her job, learning is a continuous process, and she studies how land laws are evolving in today’s Colombia. LFP helped to delineate the city’s urban perimeter, verified the geodesic network, and divided the municipality into workable intervention units. The parcel visit phase has begun and rural families in Chaparral are participating in the process. The POSPR is surveying an area of more than 88,000 hectares and approximately 8,600 parcels. More than 2,600 parcels are expected to be titled by the National Land Agency.

LFP helped to delineate the city’s urban perimeter, verified the geodesic network, and divided the municipality into workable intervention units. The parcel visit phase has begun and rural families in Chaparral are participating in the process. The POSPR is surveying an area of more than 88,000 hectares and approximately 8,600 parcels. More than 2,600 parcels are expected to be titled by the National Land Agency.

Through our analysis, we understand that deforestation in Chiribiquete is closely linked to land access and property issues and land grabbing. We see five big deforestation hotspots inside Chiribiquete that correspond to two areas in San Vicente del Caguán, two sections going towards San José del Guaviare, and one area which is the northern border of the Yaguará II indigenous reservation. Then we have zones such as San Miguel that, although they are not very large, already show evidence of deforestation.

Through our analysis, we understand that deforestation in Chiribiquete is closely linked to land access and property issues and land grabbing. We see five big deforestation hotspots inside Chiribiquete that correspond to two areas in San Vicente del Caguán, two sections going towards San José del Guaviare, and one area which is the northern border of the Yaguará II indigenous reservation. Then we have zones such as San Miguel that, although they are not very large, already show evidence of deforestation. I think that in the case of the areas around the national park, in theory it can contribute. We have the designations, such as the parks and forest reserves, but I think forest reserves have lost their validity, despite being a mechanism to ensure that the forests can be preserved and exploited in a sustainable way. With Colombia’s issues in terms of land access for rural communities, deforestation is a result not only of people colonizing the forests, but in many cases, it’s a result of government policies. In the case of the Amazon Forest Reserve, the government directed and promoted new colonies and occupation, and they did it with counterproductive policies that people still have ingrained in their heads in terms of what is required for someone to consider themselves the owner of a piece of land. So today, people who do not have grass or cows, do not feel they are owners. So, regulations and land use planning exist, but in the end, what transforms the land are the people who do not have the right tools or knowledge and receive no support from the government.

I think that in the case of the areas around the national park, in theory it can contribute. We have the designations, such as the parks and forest reserves, but I think forest reserves have lost their validity, despite being a mechanism to ensure that the forests can be preserved and exploited in a sustainable way. With Colombia’s issues in terms of land access for rural communities, deforestation is a result not only of people colonizing the forests, but in many cases, it’s a result of government policies. In the case of the Amazon Forest Reserve, the government directed and promoted new colonies and occupation, and they did it with counterproductive policies that people still have ingrained in their heads in terms of what is required for someone to consider themselves the owner of a piece of land. So today, people who do not have grass or cows, do not feel they are owners. So, regulations and land use planning exist, but in the end, what transforms the land are the people who do not have the right tools or knowledge and receive no support from the government. I think they are on multiple fronts, for example, in terms of prevention, patrolling, and control, and the application of environmental law. USAID has a number of actions and programs that are strengthening government entities, and they are carrying out projects and providing tools to the communities that allow them to make better use of their land. USAID has initiatives around communication and awareness raising that I think are vital, and that helps to bring that knowledge and that work closer to the communities.

I think they are on multiple fronts, for example, in terms of prevention, patrolling, and control, and the application of environmental law. USAID has a number of actions and programs that are strengthening government entities, and they are carrying out projects and providing tools to the communities that allow them to make better use of their land. USAID has initiatives around communication and awareness raising that I think are vital, and that helps to bring that knowledge and that work closer to the communities. If we don’t coordinate efforts and work with the communities in the northern part, Chiribiquete does not have a high rate of survival in the medium term. The process of deforestation moves fast, and every day there is more transformation. If we don’t make the indigenous communities who are protecting the southern parts of the park our natural partners, it is very likely that a time will come when there will also be deforestation in that region. So, our first challenge is to work with the communities, to make them our natural partners for conservation. Without discriminating between indigenous and farmer communities but including everyone.

If we don’t coordinate efforts and work with the communities in the northern part, Chiribiquete does not have a high rate of survival in the medium term. The process of deforestation moves fast, and every day there is more transformation. If we don’t make the indigenous communities who are protecting the southern parts of the park our natural partners, it is very likely that a time will come when there will also be deforestation in that region. So, our first challenge is to work with the communities, to make them our natural partners for conservation. Without discriminating between indigenous and farmer communities but including everyone.

Leany Alba, 28, grew up in Bogota and dreamed of being a professional photographer, but her parents never warmed up to the idea. She always loves maps and followed a career path towards becoming a cartographer. On that path, she found a burgeoning job market for her current profession: land surveyor.

Leany Alba, 28, grew up in Bogota and dreamed of being a professional photographer, but her parents never warmed up to the idea. She always loves maps and followed a career path towards becoming a cartographer. On that path, she found a burgeoning job market for her current profession: land surveyor.

“With today’s technology, there is no excuse. Any woman can work as a land surveyor.” says Leanny.

“With today’s technology, there is no excuse. Any woman can work as a land surveyor.” says Leanny. “So one of the challenges is communication with people. Women often have better communications skills, and it is necessary to have a certain tact in dealing with rural people, since almost nobody understands land” explains Leany Alba.

“So one of the challenges is communication with people. Women often have better communications skills, and it is necessary to have a certain tact in dealing with rural people, since almost nobody understands land” explains Leany Alba.

“We as coffee growers work for the common good. More than coffee, it is us, a part of the countryside who are taking care of the environment,”

“We as coffee growers work for the common good. More than coffee, it is us, a part of the countryside who are taking care of the environment,”  Fanllany Mendez and the 10 associations participated in coffee cupping, exposition of production machinery, and business meetings with buyers from Taiwan, South Korea, Mexico, Peru, China and Colombia. The coffee growers, who a decade ago had no market channels available, came to the fair to prove that in the municipalities of Northern Cauca are also producing specialty coffee with added value.

Fanllany Mendez and the 10 associations participated in coffee cupping, exposition of production machinery, and business meetings with buyers from Taiwan, South Korea, Mexico, Peru, China and Colombia. The coffee growers, who a decade ago had no market channels available, came to the fair to prove that in the municipalities of Northern Cauca are also producing specialty coffee with added value.

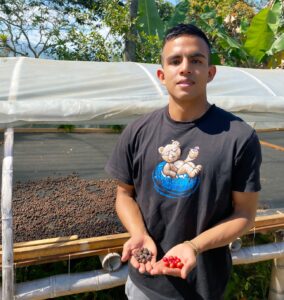

Santiago Samboní is a 21-year-old who has always grown coffee with his mother and grandmother on their farm located in the rural area of Santander de Quilichao. For Santiago, being a successful coffee grower is more than just production, it’s about training and acquiring knowledge that can improve the process. Today he is studying to become a food engineer.

Santiago Samboní is a 21-year-old who has always grown coffee with his mother and grandmother on their farm located in the rural area of Santander de Quilichao. For Santiago, being a successful coffee grower is more than just production, it’s about training and acquiring knowledge that can improve the process. Today he is studying to become a food engineer.

Tell us about yourself.

Tell us about yourself.

Eleven ethnic Pijao communities in the municipality of Chaparral, Tolima, took part in Free, Prior, and Informed Consent (FPIC) sessions and agreed to participate in the implementation of Rural Property and Land Administration Plan (POSPR) being carried out by USAID Land for Prosperity with support from the Colombian government.

Eleven ethnic Pijao communities in the municipality of Chaparral, Tolima, took part in Free, Prior, and Informed Consent (FPIC) sessions and agreed to participate in the implementation of Rural Property and Land Administration Plan (POSPR) being carried out by USAID Land for Prosperity with support from the Colombian government. “This is a great opportunity for indigenous communities to advance the process of establishing collective landholdings, strengthen our family bonds, and ensure the persistence of the Pijao culture,” says Maria Ximena Figueroa, Pijao social leader from the Matora de Maito Pijao community.

“This is a great opportunity for indigenous communities to advance the process of establishing collective landholdings, strengthen our family bonds, and ensure the persistence of the Pijao culture,” says Maria Ximena Figueroa, Pijao social leader from the Matora de Maito Pijao community. “There is confusion in the community around land formalization, ranging from ideas that the government is coming to take our land to ideas that the government is finally making reparations,” says Luis Fernando Guerrero, the current governor of Matora de Maito.

“There is confusion in the community around land formalization, ranging from ideas that the government is coming to take our land to ideas that the government is finally making reparations,” says Luis Fernando Guerrero, the current governor of Matora de Maito. In 2010, Matora de Maito purchased a three-hectare parcel to build their maloca, or community meeting center, near the urban center of Chaparral. “The problem is that we still don’t own a larger piece of collective land where we can work together and use the land the way we always have,” explains the group’s governor, Luis Fernando Guerrero.

In 2010, Matora de Maito purchased a three-hectare parcel to build their maloca, or community meeting center, near the urban center of Chaparral. “The problem is that we still don’t own a larger piece of collective land where we can work together and use the land the way we always have,” explains the group’s governor, Luis Fernando Guerrero. “We all want a collective territory where we can record our own history and leave a legacy for our children. Our communities need assistance with the application for a resguardo.” says José Walter Cano, Governor of the Pijaos en Evolución, a group of 26 Pijao families.

“We all want a collective territory where we can record our own history and leave a legacy for our children. Our communities need assistance with the application for a resguardo.” says José Walter Cano, Governor of the Pijaos en Evolución, a group of 26 Pijao families.

El Bagre is synonymous with gold mining. In fact, before El Bagre was a municipality, it formed part of neighboring Zaragoza and was a place where people had been mining gold for hundreds of years. For the last several decades, Colombian mining firm Mineros has carried out alluvial mining across large swathes of the gold-rich land. According to experts, El Bagre is one of Antioquia’s highest gold producing municipalities and depends on gold for 80-90% of its revenue.

El Bagre is synonymous with gold mining. In fact, before El Bagre was a municipality, it formed part of neighboring Zaragoza and was a place where people had been mining gold for hundreds of years. For the last several decades, Colombian mining firm Mineros has carried out alluvial mining across large swathes of the gold-rich land. According to experts, El Bagre is one of Antioquia’s highest gold producing municipalities and depends on gold for 80-90% of its revenue. In May, El Bagre’s Land Office delivered 90 property titles to residents, bringing the total number of land titles delivered to more than 500 since the office was created.

In May, El Bagre’s Land Office delivered 90 property titles to residents, bringing the total number of land titles delivered to more than 500 since the office was created. “Nobody believed the Municipal Land Office would help them with land titling services for free. But once we delivered more than 150 land titles at our first event in 2021, people gained confidence in what the administration is trying to do,” Gomez says.

“Nobody believed the Municipal Land Office would help them with land titling services for free. But once we delivered more than 150 land titles at our first event in 2021, people gained confidence in what the administration is trying to do,” Gomez says. El Bagre’s Municipal Land Office is also facilitating housing subsidies for new homeowners with a registered land title who qualify for the program. In 2023, the MLO helped 66 homeowners access government subsidies offered by Antioquia’s departmental government, permitting low-income residents to improve their flooring, bathrooms, and kitchen.

El Bagre’s Municipal Land Office is also facilitating housing subsidies for new homeowners with a registered land title who qualify for the program. In 2023, the MLO helped 66 homeowners access government subsidies offered by Antioquia’s departmental government, permitting low-income residents to improve their flooring, bathrooms, and kitchen.