Background

Community involvement in natural resource management in Zambia dates to the 1990s, when CBNRM was adopted as a model for co-managing the country’s protected areas with communities through CRBs. GMAs that border national parks cover over 20 percent of Zambia’s surface and are found in almost 30 percent of Zambia’s chiefdoms. While large portions of GMAs are not suitable for wildlife due to decades of agricultural expansion, they are still home to extensive forest habitat, and many have areas of

abundant wildlife. In the 1990s, donor-funded programs, including NORAD-funded Luangwa Integrated Rural Development Program (LIRDP) in Lupande GMA, aligned with DNPW (Department of National Parks and Wildlife Service (DNPWS) at the time) and subsequently Zambia Wildlife Authority (ZAWA) efforts to empower communities with hunting revenue and combat the poaching that had decimated Zambia’s national parks and GMAs in the 1980s. This model of CBNRM was exclusively focused on wildlife resources in GMAs, with limited oversight of other resources such as forestry, leading to progressive degradation of customary managed forests, particularly those with limited wildlife populations and areas on the edge of agricultural communities.

While community awareness and resource security has improved in the wildlife sector since the 1990s, forest resources largely remained vulnerable as essentially open access resources without any incentive for local forest protection or management. Zambia’s forest reserves cover approximately eight percent of the country, but forests are abundant across much of the remainder of the country. While the FD has management authority over these non-gazetted forests (but not the customary land that they sit on), they lack the human resources and financial capacity to actively manage forests outside of reserves. Therefore, involving local people in forest management has become increasingly necessary. In response to this growing need, the Zambian government introduced a CFM model to foster collective management of forest resources. Community involvement in forest management on customary land was first identified in the National Forestry Action Plan of 1997 as an approach to address the continuous deterioration of customary and gazetted forests. Since the 2015 Forests Act and subsequent Community Forest Management Regulations of 2018 were passed, over 200 communities have formed CFMGs and applied for forest management rights. In just five years, CFMGs now cover more than five million hectares. Importantly, CFM provides perhaps the only approach for self-defined communities to assert their community tenure over specific areas customary land and register these rights with government.

The 2015 Forests Act and the CFM Regulations of 2018 call for synergies between forest and wildlife management. This is further seen in the 2023 Community Based Natural Resource Management Policy, which was developed under the Ministry of Tourism. While the language identifies the need for management coordination, the practice to date has been lacking. The success of forest and wildlife management moving forward will largely depend on the interactions between the critical government agencies charged with separate legal responsibilities for managing forest and wildlife resources, and their approaches to supporting devolution of rights. The overlaps and gaps between wildlife and forest management are well understood in each department, as well as at the district level. The overlapping resources and local communities dictate constant engagement among field officials and there is natural coordination that occurs at the district level, albeit with little direction from the national level. However, a lack of institutional consensus on CFMG/CRB relationships regarding resource protection, revenue management, and community project support and development mechanisms using carbon and animal funds can spark antagonistic relationships between departments. This subsequently impacts their interactions with communities. There is furthermore a risk that devolution will be perceived as providing communities with responsibilities over management that they do not have the financial or technical capacity to implement. This underscores the importance of cross-department coordination.

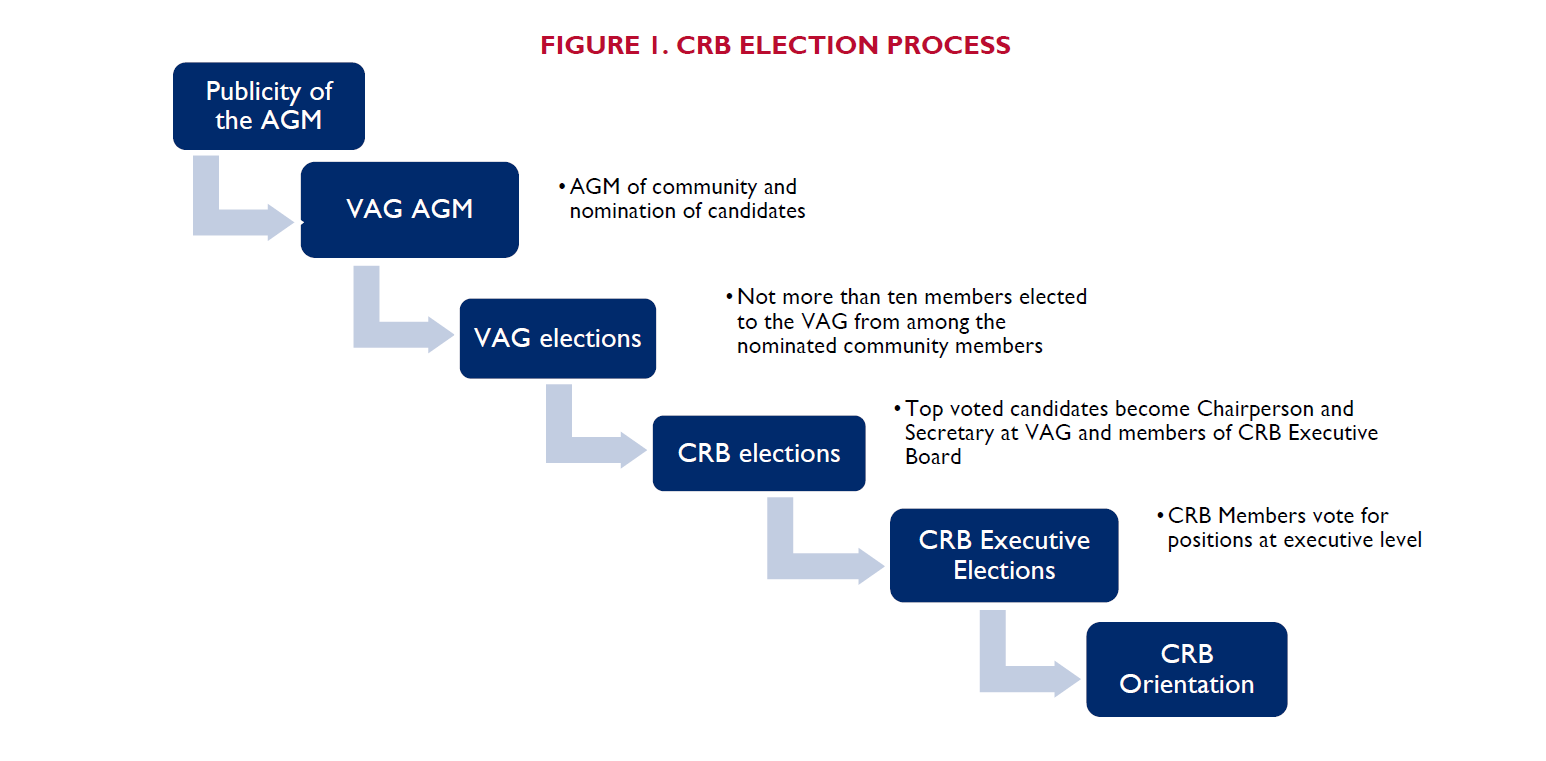

According to the CRB Election Guidelines, the VAG and CRB positions are up for election every five years, though in practice this happens every three years. The election process starts with publicity about the annual general meeting (AGM) a few days prior to the meeting. All community members are eligible to attend the VAG AGM meeting. Publicity is done through megaphones and headpersons informing people of the date of the AGM, the agenda, and the venue. During the AGM, all individuals interested to run in the election are required to file their nominations, receive an animal symbol as their identity for campaigning and receiving votes, and immediately start the campaign to get elected. The campaign is often for a short period of two to three days. Experience from previous elections show that women are often not reached by awareness-raising efforts and lack information about the process and criteria to participate in the election. The short campaign period also disadvantages women, who have limited financial resources and competing household responsibilities.

According to the CRB Election Guidelines, the VAG and CRB positions are up for election every five years, though in practice this happens every three years. The election process starts with publicity about the annual general meeting (AGM) a few days prior to the meeting. All community members are eligible to attend the VAG AGM meeting. Publicity is done through megaphones and headpersons informing people of the date of the AGM, the agenda, and the venue. During the AGM, all individuals interested to run in the election are required to file their nominations, receive an animal symbol as their identity for campaigning and receiving votes, and immediately start the campaign to get elected. The campaign is often for a short period of two to three days. Experience from previous elections show that women are often not reached by awareness-raising efforts and lack information about the process and criteria to participate in the election. The short campaign period also disadvantages women, who have limited financial resources and competing household responsibilities.

The United States Agency for International Development (USAID) and PepsiCo are partnering to promote women’s economic empowerment in the potato supply chain in West Bengal, India. The partnership aims to demonstrate the business case that empowering women makes good social and economic sense, leading to the adoption of sustainable farming practices, improved yields and income for farming families, and increased profitability for companies. The project uses multiple approaches to reach, benefit, and empower women in the potato supply chain, strengthening women’s land tenure security, creating improved livelihood and entrepreneurial opportunities for women, and promoting increased social acceptance of women’s role as farmers. This project is implemented under the Integrated Land and Resource Governance (ILRG) task order, led by Tetra Tech in collaboration with Landesa, with funding from the Women’s Global Development and Prosperity (W-GDP) Fund at USAID. During the 2019 – 2020 potato season, ILRG supported two women’s self-help groups (SHGs) to lease land and produce commercial potatoes as part of PepsiCo’s supply chain in West Bengal, India.

The United States Agency for International Development (USAID) and PepsiCo are partnering to promote women’s economic empowerment in the potato supply chain in West Bengal, India. The partnership aims to demonstrate the business case that empowering women makes good social and economic sense, leading to the adoption of sustainable farming practices, improved yields and income for farming families, and increased profitability for companies. The project uses multiple approaches to reach, benefit, and empower women in the potato supply chain, strengthening women’s land tenure security, creating improved livelihood and entrepreneurial opportunities for women, and promoting increased social acceptance of women’s role as farmers. This project is implemented under the Integrated Land and Resource Governance (ILRG) task order, led by Tetra Tech in collaboration with Landesa, with funding from the Women’s Global Development and Prosperity (W-GDP) Fund at USAID. During the 2019 – 2020 potato season, ILRG supported two women’s self-help groups (SHGs) to lease land and produce commercial potatoes as part of PepsiCo’s supply chain in West Bengal, India. This report details the outcomes and lessons learned from piloting SHG land leasing groups with the two SHGs – Subho Chandimata and Eid Mubarak – selected to participate in group leasing in the first year of the USAID-PepsiCo partnership.

This report details the outcomes and lessons learned from piloting SHG land leasing groups with the two SHGs – Subho Chandimata and Eid Mubarak – selected to participate in group leasing in the first year of the USAID-PepsiCo partnership.