Published / Updated: July 2017

We are not actively updating this country profile. If you are seeking more updated country information, please visit the country profiles provided by Land Portal and FAO.

Overview

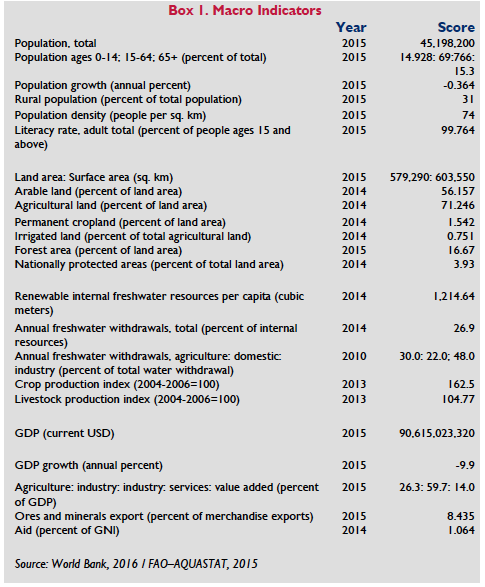

Ukraine is richly endowed with resources for agriculture, particularly fertile arable lands, placing it among the world’s largest grain and vegetable oil exporters. The country is classified as a lower-middle income economy. Over the last 20 years, the Ukrainian Republic (Ukraine) has privatized ownership of both rural and urban land, drawing upon significant amounts of technical assistance from donors, including USAID. Initial transfers of farmland from 9,350 collective and 4,659 state farms in 1992 enabled households to acquire up to 1.25 hectares of land to produce food for their own consumption. Nearly one third of Ukraine‘s 45.2 million people now live in rural areas and have ownership of some land, although not all rural households are full-time farming households. In 2007, the average family farm size was about 3.2 hectares.

Some observers note that poor environmental management, in general, is the result of weak enforcement and protection of property rights and low tenure security. A new realignment of rural property rights may be needed to realize greater agricultural productivity and income growth. Privatization of non-agricultural land has been less problematic. It is more readily registered, marketed, and transferred.

Disputes over property rights mark the Government of Ukraine‘s relationships with Russian Federation on the territories of Crimea (occupied by the Russian Federation in 2014) and certain districts of Eastern Ukraine Donetzk and Lughansk Regions (ORDLO) (also occupied by the Russian Federation in 2014) (together hereinafter the “Temporarily Occupied Territory”). With 1.785 million persons internally displaced as a result of the Russian aggression, property right issues of the Temporarily Occupied Territory are likely to remain on the agenda for some years to come.

Unsustainable farming techniques and a growing demand for fuelwood and commercial timber have decimated Côte d’Ivoire’s natural forests, which have declined from approximately 13 million hectares when the country became independent in 1960 to only 2.5 million hectares in the 1990s. Coastal wetlands are also rapidly disappearing. Soil degradation, water pollution, and loss of biodiversity pose significant threats to future productivity and the wellbeing of rural communities.

Key Issues and Intervention Constraints

While agriculture contributes relatively little to Ukraine‘s GDP – only 14 per cent (World Bank 2015), more than one third of the population continues to live in rural areas often under conditions of extreme poverty. The small size of landholdings and private farm enterprises may constrain some abilities to increase productivity. Procedures for leasing state land do not result in expected levels of marketed production. The Government of Ukraine (GOU) could improve rural land reform by phasing in the opening of the land market; testing new approaches to leasing; privatizing land still held by the state; and complementing these reforms with additional investments to make the new owners more competitive agricultural producers. GOU needs technical support for survey and title registration to ensure that reforms are administered fairly and rapidly.

Ukraine lacks efficient controls over water use. Such supervision should cover legal title to water reservoirs, compliance with key environmental and sanitation requirements and introduction of sustainable management practices. Stock-take of the water resources and their tenants is long overdue.

The water sector of Ukraine further suffers from problems related to contamination as a result of the deterioration of the sewage system and agricultural wastes, as well as low sanitary and technical standards of the water supply system. About 60 percent of existing water pipelines has deteriorated past an acceptable state. Their sanitary and technical condition is unsatisfactory.

In the forestry sector of Ukraine, fractured management and policies created a system plagued with insufficient legal enforcement, legislative gaps, and poor financing and taxation system. These problems lead to illegal logging, uncontrolled export of round timber wood and illegal amber mining which, in turn, ultimately contribute to environmental damage (e.g. soil degradation and erosion and floods in the Ukrainian Carpathians), low productivity, loss of jobs, and depopulation of certain rural areas. The Government of Ukraine could increase the effectiveness of sustainable natural resource management including (i) updating sanitary and technical standards and renovation of the water supply system and (ii) development of complex forestry protection policy. GOU needs technical support to its institutions responsible for renewable energy sources implementation in Ukraine.

Both the central and local authorities are constantly struggling with the regulation of real estate development. Existing legislation does not ensure effective oversight of either residential or non-residential construction. Excessively restrictive rules gave rise to widespread corruption which undermines control over land allocation, obtainment of construction permits, compliance with building codes and commissioning of completed construction.

Utility providers (electricity, gas, water supply and waste water management) and building maintenance services are in need of overhaul. In absence of effective state regulation of their activities, they became one of the major obstacles to construction projects. Far from providing easy access to the mains, they instead increase the overall construction budget often by up to 30 percent.

In the rural areas, the widespread challenge is location of animal farms. Both brownfield and greenfield projects are often located in close proximity to residential areas in violation of applicable sanitation/protection zones. Development of transparent procedures for the reduction of the protection zones, depending on the air and waste water treatment infrastructure, is long overdue.

Summary

Ukraine, a former Soviet republic, is a largely landscaped, lower-middle income country in which 24 percent of the population lives in poverty (2010) while a further nine percent lives in extreme poverty. Poverty is concentrated in rural areas where 30-35 percent of the population resides. Historically, agriculture has been one of Ukraine’s most important sectors, due to the country’s diverse climate and relatively good soils. Ukraine is the third largest world exporter of grain after the US and the EU. In 2014, it produced 64 million tons of grains, 2.4 percent more than in 2013 even excluding the occupied Crimea (MAPF, 2015). It has a comparative advantage in grain production due to high soil fertility, low production costs, and a strategic location. Its annual potential is estimated at 100 million tons (Hervé, 2013). Ukraine is also the largest producer and exporter of sunflower, the third largest exporter of maize, the fourth of barley, the sixth of soybean, and the seventh of poultry (MAPF, 2015).

Wheat, barley and maize represent 60 percent of the crop area. Crop production has doubled over the last decade and the production of some livestock products has also significantly increased in recent years. While agriculture has fallen from 25.6 percent to 9.3 percent as a share of gross domestic product (GDP) and from 19.8 percent to 17.2 percent as a share of employment between 1990 and 2012 (World Bank, 2015a), it was the only economic sector that displayed positive economic growth in 2014, i.e. 7 percent against -10 percent for industry and for services (EIU, 2015b). Agricultural exports remain a key engine of the Ukrainian economy, representing almost 20 percent of the value of exports. By lowering trade barriers, the recent conclusion of several bilateral trade agreements offers additional opportunities for export growth.

Wheat, barley and maize represent 60 percent of the crop area. Crop production has doubled over the last decade and the production of some livestock products has also significantly increased in recent years. While agriculture has fallen from 25.6 percent to 9.3 percent as a share of gross domestic product (GDP) and from 19.8 percent to 17.2 percent as a share of employment between 1990 and 2012 (World Bank, 2015a), it was the only economic sector that displayed positive economic growth in 2014, i.e. 7 percent against -10 percent for industry and for services (EIU, 2015b). Agricultural exports remain a key engine of the Ukrainian economy, representing almost 20 percent of the value of exports. By lowering trade barriers, the recent conclusion of several bilateral trade agreements offers additional opportunities for export growth.

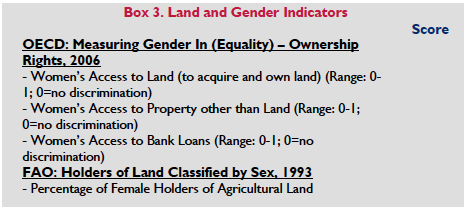

The national legislation can be mostly described as gender-neutral, while international assessments classify Ukraine with a low level of gender discrimination in social institutions (World Bank, 2016). The Constitution guarantees equal rights for men and women, including, in the inheritance of property.

According to data of the World Economic Forum, Ukraine ranks 67 out of 145 countries on Gender Gap Index 2015 with score 0.702 on equality (0=inequality; 1,00=equality).

A three year-long unresolved conflict in (i) the Crimea and (ii) certain districts of Eastern Ukraine Donetzk and Lughansk Regions (commonly, referred to by the Ukrainian abbreviation of “ORDLO”, which is translated into English as the Special Districts of Donetsk and Luhansk Regions (Oblasts)), both occupied by the Russian Federation in 2014, continues to jeopardize the population‘s ability to maintain livelihoods. Disputes over land and property are common in these areas they arise at private, state and international level. At least 1.785 million people have been internally displaced in Ukraine due to the conflict including 1 million women and 700 thousand men (Ministry of Social Policy of Ukraine http://www.msp.gov.ua/)

Since the end of communist rule in 1991, Ukraine has been struggling with land privatization. In Ukraine, transfer of land plots to private ownership started as early as the 1990s, shortly after the collapse of the USSR. However, most of the land plots formally designated for agricultural production were privatized only after 2001, when the special legislation on the division of the former Soviet collective farms and their transfer to private ownership was introduced (the “Privatization Law”). According to the Privatization Law, the farm lands used by the collective farms were to be split between the former workers of such farms, as well as the other villagers who were not members of collective farms and received household plots.

Privatization was carried out in the following two stages:

- Distribution of Land Shares. During the first stage, all the eligible individuals (usually inhabitants of a certain village) were granted special land share certificates which confirmed their right to receive a land plot of a certain size expressed in notional hectares (the “Land Share”) as private owners. The average area of each such notional land plot was calculated using statistical data for the total agricultural land bank and the number of eligible individuals in the particular region; and

- Conversion of Land Shares to Land Plots. At the next stage, licensed land surveyors prepared documentation for the parcellation of the agricultural lands ascribed to each village council. On the basis of these documents, individuals were able to exchange their Land Shares for the properly demarcated and registered land plots bearing unique cadastral numbers. As a result, agricultural land was effectively transferred into private ownership of individuals, who are predominantly villagers or their direct descendants.

While 70 percent of land has been transferred to private ownership, the new owners are not allowed under Ukrainian law to dispose of the majority of agricultural land. This prohibition (also referred to as the “Moratorium”) has been quite damaging to the development of agriculture. Unable to purchase land, agribusiness companies have been reluctant to invest in capital-intensive long-term projects. Consequently, the major focus shifted to high-margin crops, e.g. sunflower, corn and rapeseed.

The moratorium conserved the split of land banks2 into minor allotments initially transferred to the private ownership and made any land aggregation impossible. With the ever-growing demand for arable land, many agribusinesses find it increasingly difficult to secure leases for contiguous land masses. Many fields now represent a patchwork of land plots leased out to rivaling farming operations. This complicates farming and often gives rise to land disputes among the land users. It is widely accepted that any meaningful development of the land market, as well as any further land reform, is not possible without lifting the moratorium.

Cancellation of the moratorium is repeatedly debated both in the Ukrainian parliament and in the negotiations between Ukraine and its donors. This move is strongly opposed though, for different reasons, by the majority of both private landowners and agribusinesses. Private landowners, predominantly impoverished peasants, are afraid of the mass purchase of land below its market value and subsequent displacement of peasants from the rural areas. One of the common concerns is the fire sale of Ukrainian land to foreigners which has been held out by many, including some political parties. The most recent Draft Law no. 5535 “On Circulation of Agricultural Land” of 13 December 2016 proposed a gradual opening of the market land moratorium and its abolition on 1 July 2017. This provided precautions and restrictions limiting the minimum price and maximum number of hectares owned by individuals and legal entities. Also, it is important to note that, according to the Draft Law, by 2030 foreigners and stateless persons will not be able to purchase Ukrainian agricultural land.

Agribusinesses, in turn, are more concerned with the absence of inexpensive bank lending which will make it difficult for them to purchase the currently leased land. They fear that landowners willing to sell their land plots will turn to the highest bidder. Ukrainian law protects land tenants and secures their use of the leased land plots until expiration of the lease. Ukrainian law further grants tenants the right of first refusal in the case of sale of the leased land. Nonetheless, it is feared by the agribusinesses that landowners might try to seek early termination of land leases every time the tenant is not willing to buy or is not able to offer the highest price. In view of the number of landowners with whom even medium-sized agribusinesses have to interact (thousands to tens of thousands of individuals), sale offers from even 10 percent of the community, if unmatched, might pose a material legal and practical threat to the stability of business operations.

Both domestic and foreign investment in agriculture has increased over the last decade, although agricultural investment as a share of total investment remains low. European countries represent the main source of foreign direct investment, with large European and American agribusiness companies planning to significantly increase their investments in the coming years, despite political uncertainty. Investors from China and the Gulf countries are also starting to invest heavily in the sector. While Ukraine has rapidly improved its position in business climate rankings, it could improve further in some areas, such as state regulation. The recently developed ‘Strategy for Agriculture and Rural Development 2015-20’ should help Ukraine leverage its potential, including by furthering its integration with the EU.

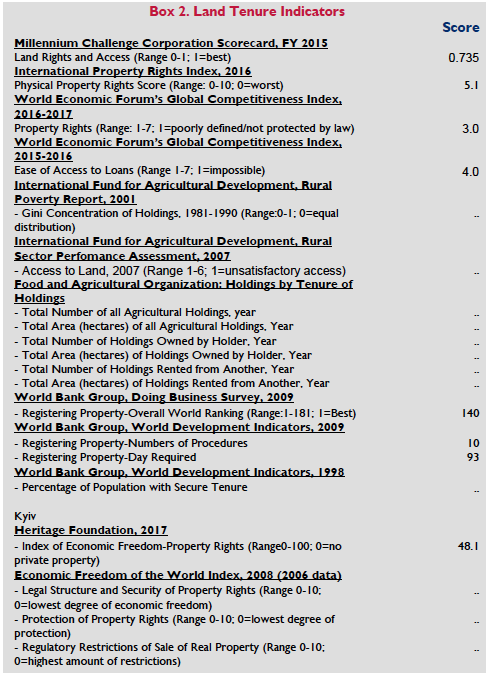

Many procedures, that provided fertile ground for corruption, are being streamlined following the adoption of the Law of Ukraine “On Amending Some Legal Acts of Ukraine to Streamline Conditions For Doing Business (Deregulation) No. 191-VIII in early 2015. Ongoing institutional arrangements for investment policy may also help address the above-mentioned challenges. At the same time, land governance in Ukraine has been criticized for its slow pace of reforms, limiting constitutional rights of land owners, corruption and inefficiency (as summarized in the WB LGAF Report, 2013). Pilot results of Land Governance Monitoring implemented in 2015 by the World Bank-funded Project “Capacity Development for Evidence-Based Land & Agricultural Policy Making in Ukraine” jointly with the Ministry of Agrarian Policy and Food of Ukraine and several other government authorities, portray the current state of land governance at the local (district/city) level and establish infrastructure for tracking progress with land reform (“Vox Ukraine” on 7 October, 2016).

Although Ukraine has rich water resources, the water sector suffers from ineffective management and low sanitary standards of the water supply system. Sixty percent of the existing water pipelines have deteriorated, and sanitary and technical conditions are unsatisfactory. In addition, water distribution is uneven. Annual droughts are common in the southern and south-eastern region. In many of those areas, irrigation is necessary for agricultural production.

Ukraine’s forests are of vital importance to the country’s economy and environmental well-being. At the same time forestry sector is contributing a very small portion to GDP of Ukraine– only 0.5 percent (FEAO, October 2016). Major differences in forest conditions– as well as social and economic conditions – have led to overlap and duplication of effort and responsibilities between the Ministry of Ecology and Natural Resources of Ukraine, the Ministry of Agrarian Policy and Food of Ukraine and State Forest Agency when it comes to daily management. At the moment, the State Forest Resources Agency, coordinated by the Ministry of Agrarian Policy and Food, is responsible for 68 percent of Ukrainian forests. The Ministry itself is responsible for another 17 percent. Recently established municipal agrarian forest enterprises are responsible for managing forests on state land. Over time, fractured management and policies created a system plagued with insufficient legal enforcement, legislative gaps, and a poor financing and taxation system. This has led to illegal logging, uncontrolled export of round timber wood and illegal amber mining – which, in turn, ultimately leads to environmental damage (soil degradation and erosion and floods in the Ukrainian Carpathians), low productivity, loss of jobs, and depopulation of certain rural areas. The forestry sector could more than double its contribution to the national economy while also better ensuring sustainable provision of public goods, such as watershed management, control of erosion and flooding, conservation of landscape and biodiversity, and the opportunity for recreation and tourism (World Bank, 2006).

Before 2014, Ukraine was among the world’s leading producers of a number of minerals. It was one of the world’s top four producers of gallium, the 4th-ranked producer of rutile (which accounted for 2.2 percent of world output), the 5th-ranked producer of titanium sponge (3.0 percent), the 6th-ranked producer of iron ore (2.6 percent), the 9th-ranked producer of steel (2.0 percent), the 10th-ranked producer of manganese ore (1.8 percent), and the 11th-ranked producer of ilmenite (2.2 percent) (Mineral Yearbook, 2012). The country has significant coal resources; however, they do not meet all of its needs. Following the start of the war with the Russian Federation and the temporary occupation of ORDLO, Ukraine has lost its position as a leading producer of minerals. Also, Ukraine has lost, albeit temporarily, a significant part of its coal deposits, in particular, those used for the power generation. While some of the coal mined in ORDLO does find its way to the Ukrainian market, is not sufficient to meet the regular demands of the Ukrainian power sector. The recent blockade of the trade with ORDLO, spearheaded by the war veterans and a number of public organizations, brought supply of this coal to a halt. As a result, Ukraine has become more dependent for its fossil fuel power generation on imported coal.

Ukraine has considerable deposits of both oil and natural gas. However, the current extraction is not sufficient to cover all the needs of the country. Furthermore, of the five oil refineries situated on the territory of Ukraine, only one is operational. Thus, Ukraine depends on imported petroleum and natural gas to meet domestic demands (Bedinger, 2015a, b; Corathers, 2015; Fenton, 2015; Jaskula, 2015; Tuck, 2015). The country has historically played an essential role as a transport route for oil and gas out of the Russian Federation and the Central Asia to world markets. Under the Soviet Union, major oil and gas pipelines were built through the territory of Ukraine. Following several major trade disputes and the war, the Russian Federation has been developing alternative transportation routes around Ukraine. Despite those efforts, for the next five to ten years Ukraine will remain one of the major transit countries for pipeline transportation of both Russian oil and gas to the European market.

Land

LAND USE

The agricultural sector plays a major role in the Ukrainian economy. Ukraine has a total land area of 60,355,000 hectares and a 2015 population of 45.2 million people. Thirty one percent of the total population is rural (FAO, 2015). Agricultural land makes up 68 percent of total land area. Irrigated lands comprise 0.75 percent of the total area of agricultural land. About 57 percent of land area is arable, 2.7 percent is permanent cropland, and an additional 11 per cent is utilized as permanent pasture land. Around 16.6 percent of the total land area is forested (Andre Schmitz and William H. Meyers, CAB International, 2015).

Ukraine’s 2015 GDP of USD 90.615 billion consisted of 13.3 per cent agriculture, 24.4 per cent industry, and 62.7 per cent services (World Bank 2016, Index Mundi, CIA World Factbook 2016). About 54 per cent of employed Ukrainians work in the agricultural sector. Ukraine is a lower middle income, food deficient country. Historically, agriculture has been one of Ukraine’s most important sectors due to the country’s diverse climate and relatively good soils. Following the dissolution of the Soviet Union (USSR), Ukraine’s agricultural output declined dramatically due to political instability and the severance of trade ties with other former Soviet republics. As a result, Ukraine became a net importer of agricultural products. Ethnic Ukrainians, constituting 77.8 percent of the population, live throughout the country. The remaining 22.2 percent are ethnic minorities consisting of Russians (17.3 percent), Belarusians (0.6 percent), Moldovans (0.5 percent), Crimean Tatars (0.5 percent), Bulgarians (0.4 percent), Jews (0.2 percent), Armenians (0.2 percent), and Greeks (0.2 percent) (Michel Moser, Stuttgart, Germany 2014). In Ukraine, a state with a food surplus, product availability was not considered a problem until the conflict in ORDLO began in 2014. At least 1.785 million people have been internally displaced in Ukraine due to the conflict including 1 million women and 700,000 men (Ministry of Social Policy of Ukraine http://www.msp.gov.ua/).

LAND DISTRIBUTION

Pre-Privatization Period. During the Soviet regime, Ukrainian agriculture was organized in two centrally controlled sectors of large scale farming through collective farms (so-called “Kolkhozes” and “Sovkhozes”). Kolkhozes were collective farms in which output and all assets were jointly owned by the members. Sovkhozes were state farms in which output and all assets were owned by the state. In addition to these centrally organized sectors, an important part of agricultural production originated in individual subsidiary farms, such as household plots of individual kolkhoz/sovkhoz members and garden plots assigned to city workers. The reorganization of the kolkhoz/sovkhoz sector began in 1992. Most of the farms have gone through some reorganization and at least changed their ownership titles during the last years.

Actual land reform in Ukraine started with the Resolution of the Verkhovna Rada (Ukrainian Parliament) “On Land Reform” of 18 December 1990, which declared all land in Ukraine subject to land reform beginning on 15 March 1991. According to the preamble of the Resolution, land reform is understood as a part of the large-scale economic reform in Ukraine, related to the shift towards a market economy (Katja Dells, Pieter Steffens and others, State Land Management of Agricultural Land in Ukraine, Berlin 2006). The task of land reform is described as the redistribution of land with simultaneous transfer of land into collective and private ownership as well as for the use of enterprises and organizations with the purpose of creating conditions for equal development of all economic activities using land, and securing the rational use and protection of the land. Historically the land reform in Ukraine can be divided into the following periods:

- 1990-1992. In this, the principal legal basis for land reform was created with the Land Code of 1990. The creation of private farms was permitted in 1990. The GOU initiated a program to establish private farms3. Laws passed at this stage initiated the land reform process. However, they soon became outdated and subject to revision and amendment.

- 1992-1994. In this period, an inventory of land was carried out, and the so-called Reserve Fund was created using the agricultural land formerly used by collective and state farms. Land from this Reserve Fund was meant to be distributed to Ukrainian citizens (i.e. those living and working in rural areas) for purposes of gardening, housing, personal peasant farms, etc. This was also referred to as the distribution of household plots to households.

- 1995-1999. Under Decree of the President of Ukraine “On Immediate Measures for Speeding up Land Reform in the Sphere of Agricultural Production” dated 10 November 1994 the conversion of collective farms into so-called collective agricultural enterprises and the introduction of collective ownership with a mass transfer of state owned land into the collective ownership of such collective farms. Under Decree of President of Ukraine “On the Procedure for the Sharing of Land Transferred into Collective Ownership of Agricultural Enterprises and Organizations” dated 8 August 1995 the distribution of land shares started in 1996 and had mostly been completed by 1998. As a result, members of collective agricultural enterprises were given so-called land certificates confirming the right of allocation of a land plot of a certain size.

- 1999-present. Under the Presidential Decree “On Immediate Measures for Speeding up Reforming of the Agricultural Sector of the Economy” dated 3 December 1999, collective agricultural enterprises were restructured into agricultural enterprises of a new type, built upon private ownership of assets and land. By the end of 2000, practically all collectively owned land had become privately owned through the issuing of land certificates. Most private owners leased back their land shares to collective agricultural enterprises from which they received their shares (Katja Dells, Pieter Steffens and others, State Land Management of Agricultural Land in Ukraine, Berlin 2006). The Land Code of Ukraine dated 25 October 2001 was adopted introducing the Moratorium to dispose of the majority of agricultural land,

Over the past fifteen years, the overwhelming majority of the reorganized collective and state-owned farms have either been liquidated or are at various stages of bankruptcy proceedings. Their number slumped from 14 thousand to less than 1 thousand. They have been supplemented by either individual farmers (small-time individual or family farming operations working usually on 10 to 1,000 ha of land) or medium-scale to large private agribusinesses. Remaining farms are also close to be privatized. The largest agricultural concerns presently farm around 10 percent of all the agricultural land in Ukraine and continue to grow.

Over the past fifteen years, the overwhelming majority of the reorganized collective and state-owned farms have either been liquidated or are at various stages of bankruptcy proceedings. Their number slumped from 14 thousand to less than 1 thousand. They have been supplemented by either individual farmers (small-time individual or family farming operations working usually on 10 to 1,000 ha of land) or medium-scale to large private agribusinesses. Remaining farms are also close to be privatized. The largest agricultural concerns presently farm around 10 percent of all the agricultural land in Ukraine and continue to grow.

According to official statistics, approximately 90 percent of the agricultural land was thus privatized (Ukrstat, 2013a).

The average area of a privately held agricultural land plot is 4.2 hectares. However, cultivation of a land plot of that size is often not economically justified. To benefit from economies of scale, , up to 80 percent of the agricultural land plots are now leased to agricultural producers, predominantly agricultural corporations most of which cultivate at least 1,000 hectares of agricultural land.

LEGAL FRAMEWORK

The Constitution recognizes the right to property and prohibits restrictions on the right to acquire, alienate, and inherit property, with a few exceptions. The key statutes governing ownership of land and land use rights include the following:

- the Land Code of Ukraine dated 25 October 2001 (last amended 2017, hereinafter – the “Land Code”);

The Land Code is the main statute governing the ownership and use of land in Ukraine. Inter alia, the Land Code divides all the land by its formal designated use: e.g., agricultural, residential, forest, commercial, etc. Furthermore, it contains provisions regulating the classification of land ownership rights, the right to use land, limitations on the right to land, the disposal of land plots, and the resolution of land disputes. The Land Code recognizes private, municipal and state ownership on land. Under Article 84 (1) of the Land Code all land, except land in municipal and private ownership is state-owned. Municipal land is land within the boundaries of settled areas, except for privately or state-owned land. According to Article 80 of the Land Code the ownership rights of the state are exercised by relevant bodies of state power, while those regarding municipal land are exercised through local self-government bodies. The Land Code foresees four ways of dealing with state owned agricultural land: lease, permanent use and sale as well as gratuitous privatization within the scope of land reform as explained above. In addition, under the Land Code every citizen of Ukraine has the right to receive into ownership land parcels of up to 2 hectares for personal agricultural production, 0.12 hectare for gardening, 0.25 hectare for construction of private house, 0.1 hectare for cottage construction, and 0.01 hectare for garage construction.

- the Law of Ukraine “On Land Lease” dated 06 October 1998 (last amended in 2016, hereinafter – the “Land Lease Law”);

The Land Lease Law is the main statute for commodity agriculture. It regulates lease of land in all categories including agriculture land under the Moratorium. It defines the rights and duties of both landlords and tenants and regulates their interaction. Provisions of the Land Lease Law are fully applicable to the lease of state owned agricultural land. According to Article 19 of the Land Lease Law, the lease term shall not exceed 50 years. Also under Article 21 (2) of the Land Lease Law the land lease rate is defined by the agreement of the parties. In the case of lease of either state or municipal land, the lease rate shall not be lower than the land tax or higher than 12 percent of the normative monetary valuation of the land plot.

- the Law of Ukraine “On State Registration of Property Rights to Immovable Property and Its Encumbrances” dated 01July 2004 (last amended 2016, hereinafter – the “Real Estate Registration Law”);

The Real Estate Registration Law is the key law related to securing land title and lease rights. It provides that land title should be recorded in the State Register of Property Rights to Real Estate. The Register contains information on both land plots and any real estate situated on it. Its primary purpose is to make public any legal rights in respect of the real estate. These primarily include ownership and any encumbrances, including any right of use and mortgage.

- the Law of Ukraine “On State Land Cadastre” dated 07 July 2011 (last amended 2017) (hereinafter – the “Land Cadaster Law”)

The Land Cadaster Law is vitally important for identification of every particular land plot using its unique cadastral number. It provides information which is specific to each such land plot. Records on each land plot must be submitted to the State Land Cadaster. The Land Cadaster Law governs operation of the State Land Cadaster.

TENURE TYPES

In Ukraine land tenure types, may be classified into corporate farms, peasant farms (both using leased land massive), and household plots (may use privately owned land plots).

Corporate farms include large holdings that mainly operate on leased land and are commercially oriented. They include joint-stock or limited liability companies and private enterprises managed by an entrepreneur with privately owned assets. They number around 17,500 and account for approximately 60 percent of agricultural land – down from nearly 95 percent prior to 1990 – and 40 percent of gross agricultural output.

Approximately 43,000 peasant farms account for 8 per cent of agricultural land and 5-10 percent of gross agricultural output.

Around 5.3 million household plots that are generally small and largely subsistence-oriented account for 30 percent of agricultural land and almost 50 percent of agricultural output. In recent years, large-scale investments led to land consolidation: by mid-2011, 79 large holdings operated on 5.1 million hectares, i.e. about 12 percent of agricultural land, with some covering up to 500,000 hectares (Lissitsa, 2010; Visser and Mamonova, 2011; EU, 2012).

SECURING LAND RIGHTS

The Constitution of Ukraine (1996; last amended in 2016, hereinafter – the “Constitution”) protects private ownership, which includes, in particular, free disposition and use of the privately-held property by its legal owner. Land ownership is registered in two publicly accessible state registers – (i) the State Register of Property Rights to Real Estate (hereinafter – the “Real Estate Register”) and (ii) the State Land Cadaster (hereinafter – the “Land Cadaster”). The two registers differ in their focus but are interconnected. The Real Estate Register provides information on both land plots and any real estate situated on it. Its primary purpose is to make public any legal rights in respect of the real estate. These primarily include ownership and any encumbrances, including any right of use and mortgage. The Land Cadaster focuses only on the land plots. Its main function is to identify each land plot using its unique cadastral number and provide information which is specific to each such land plot. This information will include, inter alia, location of the land plot, its area, type of ownership, identity of the owner and quality of the soil. In most cases, the information collected for plots which have been registering since 2013 is accurate and dependable. But for records made before 2013 significant work must be done to provide reliable and unified information.

The system of state registration of title to land has been undergoing constant modernization and improvement. A significant boost came from introduction of the revised Real Estate Register combining information on the owners of land plots and real estate situated on them. Until 2013, this information was split between the Real Estate Register (for buildings) and the Land Cadaster (for land plots), both of which were not publicly accessible. The next significant step was opening of the two state registers to the public, including the launch of an interactive public cadastral map (see at http://map.land.gov.ua/kadastrova-karta), in 2014 – 2016. This was an outcome of the Revolution of Dignity4 and came as a response to its demand for combating corruption and overregulation.

Following the above changes in the registration of title, Ukraine has improved its ratings in registering property in the World Bank Ease of Doing Business from # 158 in 2013 to # 98 in 2014 (Ukraine Investment and Business Guide, 2015). Also, such changes are leading to a more vibrant real estate market.

Presently, registration of the property rights to real estate, including land plot, can be done through a special state registrar or a public or private notary. It takes less than one hour. The cost of title registration is under UAH 1,000 (Ukrainian hryvnyas), which is equal to approximately USD 40 at the current UAH/USD exchange rate. In the case of a land plot not registered in the Land Cadaster (these are the land plots registered prior to the introduction of the cadastral numbers in 2010), title registration will require prior entry of information on the land plot in the State Land Cadaster. This involves preparation of a special set of documents describing the land plot. The cost of such registration in the Land Cadaster, depending on the form and area of the land plot, will vary from UAH 2,000 to UAH 8,000, which is equal to around USD 77 to USD 307 at the current exchange rate.

Since 2000, Ukraine has developed the legislative and administrative basis for a mortgage market. Adoption of the Laws “On Withholding Land Shares in Kind” (2002) and “On Mortgage” (2003) was particularly important. At the same time, the number of registered mortgage agreements in 2013-2015 on land is quite low (about 90 agreements for 53 hectares in total) (Monitoring of Land relations in Ukraine 2014-2015. Statistic Yearbook, World Bank project). Thus, this type of market has not yet developed.

The Law of Ukraine “On Securing the Rights and Freedoms of Citizens and the Legal Regime on the Temporarily Occupied Territory of Ukraine” of 15 April 2014 (as amended in May 2014) defines the status of the territory of Ukraine temporarily occupied as a result of the Russian Federation’s armed aggression (hereinafter – the “Law on Temporarily Occupied Territory”). The Law on Temporarily Occupied Territory establishes a special legal regime for this territory, defines the special aspects of operation of state bodies, local self-governance bodies, enterprises, institutions, and organizations under this regime, adherence to and protection of human and citizen rights and freedoms, as well as of rights, freedoms, and lawful interests of legal entities. Acquisition and termination of property rights over real property on the Temporarily Occupied Territory is effected in accordance with the laws of Ukraine. Any legal agreement on the Temporarily Occupied Territory that concerns real property, including land plots, which does not comply with the applicable requirements of the Law on Temporarily Occupied Territory or other laws of Ukraine, is null and void from the moment of its conclusion.

The ownership of all natural resources and all other property that are located within the Temporarily Occupied Territory and/or ORDLO, must be considered as the property of Ukraine; all of that may not be transferred to other states, legal or natural person in a manner different of what is envisaged by the law of Ukraine (GOU/Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Ukraine 2017).

INTRA-HOUSEHOLD RIGHTS TO LAND AND GENDER DIFFERENCES

According to the data of the World Economic Forum, Ukraine ranks 67 out of 145 countries on Gender Gap Index 2015 with the score of 0.702 on equality (0=inequality; 1,00=equality)5. The national legislation can be mostly described as gender-neutral, while international assessments assign Ukraine a low level of gender discrimination in social institutions (World Bank, 2016). The Constitution guarantees equal rights for men and women, including the inheritance of property. Under the Civil Code of Ukraine (2003), women enjoy rights to conclude agreements on their own behalf, and to own, manage, and dispose of property.

The Land Code and the Civil Code also guarantee equal rights for men and women in respect of land and other assets. The Civil Code provides that spouses enjoy equal rights to property and personal items, and share household responsibilities within a marriage. Property acquired during the marriage is common property, unless otherwise agreed in a prenuptial agreement. The sale of marital property requires the consent of both spouses. Spouses may also have separate property, such as property acquired by any spouse before the marriage, property acquired as a gift during marriage, and personal items acquired during the marriage. Upon divorce, spouses are entitled to an equal distribution of the marital property, unless otherwise agreed. A court may deviate from this principle in the best interests of the children or one of the spouses. The surviving spouse, children, and parents inherit on an equal basis. Despite the relatively favorable legal framework governing women‘s access and rights to land, women in Ukraine (particularly elderly rural women) lack information about their rights. In Ukraine, there are no customary norms that make it difficult for women to exercise their legal rights on land or other property.

The Land Code and the Civil Code also guarantee equal rights for men and women in respect of land and other assets. The Civil Code provides that spouses enjoy equal rights to property and personal items, and share household responsibilities within a marriage. Property acquired during the marriage is common property, unless otherwise agreed in a prenuptial agreement. The sale of marital property requires the consent of both spouses. Spouses may also have separate property, such as property acquired by any spouse before the marriage, property acquired as a gift during marriage, and personal items acquired during the marriage. Upon divorce, spouses are entitled to an equal distribution of the marital property, unless otherwise agreed. A court may deviate from this principle in the best interests of the children or one of the spouses. The surviving spouse, children, and parents inherit on an equal basis. Despite the relatively favorable legal framework governing women‘s access and rights to land, women in Ukraine (particularly elderly rural women) lack information about their rights. In Ukraine, there are no customary norms that make it difficult for women to exercise their legal rights on land or other property.

LAND ADMINISTRATION AND INSTITUTIONS

The system land administrative institutions are formed by:

- The State Service of Ukraine for Geodesy, Cartography and Cadastre (the “State Geo Cadaster”) is the central executive body that is coordinated by the Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine via the Vice-Prime-Minister of Ukraine – the Minister of Regional Development, Construction and Housing of Ukraine.

The State Geo Cadastre is responsible for implementation of the state policy concerning topography, geodesy, cartography, land relations and the State Land Cadaster. The key functions of the State Geo Cadastre are the administration of the State Land Cadastre, providing the state registration of land parcels as pieces of real estate, management of the state-owned agricultural land, exercise of the state control over topography, geodesy and cartography, administration of the State Register of Land Surveyors and launch and administration of the National Register of Geographic Names.

- The Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine adopts decision on the disposal and/or use of state-owned land or land transfer under certain circumstance, e.g. land with high-value soil or acquisition of land plots by foreign legal entities outside of settlements.

- Region (oblast) councils which manage and dispose of municipal land in co-ownership of area communities, lands in reserve.

- Municipal councils (including city, town and village) which manage and dispose of the municipal land within the boundaries of each settlement. Due to the progress of decentralization in Ukraine this issue becomes more and more important. According to the Land Governance Monitoring (implemented in 2015 by the World Bank) demarcation of boundaries of towns, villages and other settlements in Ukraine is incomplete. Only 50 settlements out of 29,772 have formally registered boundaries by the end of 2015, which undermines the legitimacy of any decisions regarding land allocation made by local councils. It is also a source of land conflicts in several regions. The current consolidation of the local communities for the purpose of their self-government, which leads to the significant decrease in the number of local councils, as well as the enlargement of the areas governed by the remaining local councils, adds complexity to the demarcation issue.

- the Ministry of Agrarian Policy and Food of Ukraine which manages and disposes of the lands used by the National Academy of Science of Ukraine (hereinafter – NAAS), as well as indirectly controls the land used by a number of state-owned agricultural companies, the majority of which are at various stages of bankruptcy or liquidation. NAAS uses about 400,000 hectares of state owned land on the basis of permanent use6. NAAS has been criticized for lack of clear opportunities to monitor their management on the land and corruption due to transferring land missives into sub-lease to private companies and farms.

LAND MARKETS AND INVESTMENTS

Land markets in Ukraine, although not fully functioning, are continuing to develop and have become more active in some areas. Ukrainian law recognizes the protection of private property and freedom of disposal of private property by its owners. At the same time, there is a special prohibition of the sale of the main types of privately owned agricultural land – as a result of the Moratorium. For more than 15 years, transfer of ownership to the major part of Ukrainian farm lands has not been allowed; these lands are available for lease only. In particular, the Moratorium prohibits both sale and/or change of formal designated use of (i) any commodity (commercial) agricultural land plots; or (ii) land plots allotted for individual agriculture privatized in exchange for the Land Shares. The Moratorium also prohibits sale of the Land Shares which for any reason are not converted into the private ownership of a land plot. Approximately 75 percent of the agricultural land plots in Ukraine fall under the Moratorium (OMP, 2012).

The main argument for introduction of the Moratorium back in the middle of the 2000s was to protect land owners from possible underpriced sales of agricultural lands. In 2001, the Moratorium was introduced as a temporary measure. It was scheduled to expire in 2005. However, the expiry date was shifted several times. The latest provisions of the Land Code on the Moratorium provide for its lifting when and if the Ukrainian parliament (Verkhovna Rada) adopts the special Law of Ukraine “On Land Market” (the “Land Market Law”) but not earlier than 1 January 2018. This limitation may be changed by a simple majority vote in the Parliament of Ukraine. However, there is currently not widespread political consensus on the regulation of markets for agricultural land.

Over the years, there have been numerous drafts of the law on land markets. All of these drafts sought to address the following key issues: restrictions on the size of agricultural land bank which may be privately (whether by an individual or a legal entity) held, restrictions on the purchase of agricultural land by legal entities or non-Ukrainian nationals and residents, minimum purchase price of one hectare of agricultural land, and persons with the right of first refusal in respect of agricultural land (neighbors, state, local community, relatives, tenants, etc.). The most recent Draft Law no. 5535 “On Circulation of Agricultural Land” of 13 December 2016 proposed a gradual opening of the market land moratorium and its abolition on 1 July 2017. This provided precautions and restrictions limiting the minimum price and maximum number of hectares owned by individuals and legal entities. It is important to note that, according to the Draft Law, by 2030 foreigners and stateless persons will not be able to purchase Ukrainian agricultural land.

The compliance of the Moratorium with the Constitution has never been tested by the Constitutional Court of Ukraine (the “Constitutional Court”), the special judicial body authorized to decide on constitutionality of Ukrainian laws. In February 2017, fifty-five members of the Ukrainian parliament (Verkhovna Rada) addressed the Constitutional Court on revising the Moratorium7. In accordance with the rules of the Constitutional Court, the decision in this case is to be adopted within six months from the date of application. In accordance with Ukrainian law, the Moratorium must be lifted.

COMPULSORY ACQUISITION OF PRIVATE PROPERTY RIGHTS BY GOVERNMENT

The Constitution protects private ownership, which includes free disposition and use of privately held property by its legal owner. Any involuntary seizure or confiscation of assets is prohibited unless specifically allowed by the main law, as is the case, for example, with taxation or land acquisitions for public purposes.

The procedure for compulsory acquisition of a land plot from a private owner is regulated by the Civil Code and the Land Code. In accordance with these statutes, the state may take privately held land in order to fulfill a social need. To be valid and lawful, such expropriation must comply with the applicable statutory requirement and appropriate compensation must be paid. Settlement for the nationalized land plot must be based on a market valuation conducted by an independent certified appraiser. The law provides a mechanism for payment of compensation and for court review of the valuation at the request of any party. Compensation may be in the form of property of equal value, as well as money (Article 351 of the Civil Code). Compensation must be paid promptly and must include both the value of the expropriated property and the loss suffered as a result of expropriation. Pressing social needs include the construction of a road or highway, installation of railway tracks, installation of electrical or other utility lines, and other similar projects and activities. The expropriator, who has been awarded the right of expropriation, must agree in advance upon the amount and timing of the compensation to be paid to the owner of the expropriated property (Article 351 of the Civil Code).

LAND DISPUTES AND CONFLICTS

Under Article 158 of the Land Code, local municipal councils are authorized to resolve land disputes within the boundaries of settlements concerning the land which is owned and used by citizens and disputes over demarcation of boundaries of districts in cities. Also, State Geo Cadastre is authorized to resolve land disputes concerning the land outside the settlements, the location restrictions in land use and land easements (servitudes). Decisions of these bodies may be appealed to Ukrainian courts.

Land disputes have undermined confidence in the impartiality of the Ukrainian judicial system and rule of law. There are many concerns about the competence, independence, and impartiality of Ukrainian courts. In some cases, lower courts ordered transfer of control of property, or of entire enterprises, on questionable legal grounds or on the basis of forged documents. Higher courts have reversed some, but not all, of these decisions.

The territories of the Crimea and certain districts of Eastern Ukraine Donetzk and Lughansk Regions (ORDLO) are also experiencing major land disputes. Ukraine considers these areas are illegally occupied by the Russian Federation, and the Russian Federation claims that the territories have proclaimed their independence from Ukraine. These disputes will need to be resolved through political negotiation on an international level.

KEY LAND ISSUES AND GOVERNMENT INTERVENTIONS

Land governance in Ukraine has been criticized for slow pace of reforms, limiting constitutional rights of land owners (the Moratorium), corruption and inefficiency (as summarized in WB LGAF Report, 2013). While agriculture contributes relatively little to Ukraine‘s GDP, more than one third of the population continues to live in rural areas, often under conditions of extreme poverty. The small size of landholdings and private farm enterprises may constrain the ability of some to increase productivity. The Moratorium conserved the split of land banks into minor allotments initially transferred to the private ownership and made any effective land aggregation impossible. With the ever-growing demand for arable land, many agribusinesses find it increasingly difficult to secure leases of contiguous land masses. Many fields now represent a patchwork of land plots leased out to rival farming operations. This complicates the farming and often gives rise to land disputes among competing land users. It is widely accepted that any meaningful development of land market, as well as any further land reform, is not possible without lifting the Moratorium.

Procedures for leasing state land have not resulted in expected levels of marketed production. Thus, the GOU needs assistance to develop another wave of rural land reform, including phased opening of the land market; implement improved land market monitoring system to track land policy implementation; develop a private sector land mortgage market; the testing of new approaches to leasing the state land; and complementing these reforms with additional investments to make the new owners more competitive agricultural producers.

Evaluation of land is another area of concern. Valuation of urban and rural land in Ukraine is complicated. There is lack of data about sale prices for land. A so-called normative monetary evaluation of land is used as a base for land taxes and land lease payments. The system of normative monetary evaluation of land is based on numerous normative documents rather than on market data. Such system should be re-considered before the lifting the Moratorium.

For effective management of state and municipal land the following steps may be required:

- acceleration of demarcation and proper registration of the land plots in state and municipal ownership;

- provision of clear and accurate access to information on state and municipal land available for rent/use and on the conditions for its acquisition and use (i.e. consider expanding the functionality of e-services through the State Land Cadaster portal, including information on land availability throughout the whole country, down to the region and district levels);

- revision of applicable laws and regulatory acts in relation to the valuation of property subject to expropriation for public needs or necessity in order to ensure a balance between private and social interests concerning land and other natural resources.

Of separate concern is the issue of soil preservation and proper land use. While Ukraine has abandoned the Soviet tradition of control over crop rotation, it is yet to develop new effective controls aimed at monitoring the chemical composition of the soil and preventing soil depletion through incorrect or destructive farming practices.

DONOR INTERVENTIONS

Since 1992, USAID has contributed approximately USD 1.9 billion to Ukraine’s economic and social development. Land titling and cadastral development have been a major focus of international donors. Assistance has included providing an assessment of the land tenure situation and drafting key legal documents, laws, and procedures for early registration of the newly allocated parcels of both agricultural and non-agricultural land. For example, the recently completed USAID-funded AgroInvest Project was a five-year (2011-2016) program designed to provide technical assistance to accelerate and broaden economic recovery in Ukraine and increase the country’s contribution to global food security efforts. Ukraine required assistance to tap its vast potential in agriculture, thereby diversifying its pathways of prosperity, leading to broader economic recovery and contributing to a more food secure world. The project consisted of three components, implemented in parallel: Component 1: Support a Stable, Market-Oriented Policy Environment; Component 2: Stimulate Access to Finance; and Component 3: Facilitate Market Infrastructure for Small and Medium Producers. Under the AgroInvest project USAID worked with local stakeholders to reform agriculture policy to lift the moratorium and to increase agricultural productivity and investment. The project also has conducted analysis for the Ministry of Agrarian Policy and Food and the State Land Agency on proposed legislation related to land use planning and registration of lands, and supported creation of a Land Rights Resource Center with the Land Union of Ukraine. To support transparent and accessible information to land rights, the project developed and regularly updated the “Manual on Forming Land Plots and Registering Rights to Them” for distribution among all individuals who have a stake in land registration. AgroInvest worked closely with the Ministry of Justice to train state land registrars and public notaries throughout the country on the use of the new online land cadastral system.

Currently, USAID implements the Agriculture and Rural Development Support Project (ARDS project) in Ukraine. The ARDS project will support broad-based, resilient economic growth through a more inclusive, competitive, and better governed agriculture sector that provides attractive livelihoods to rural Ukrainians. It will create a better enabling environment for agricultural small and medium enterprises by strengthening the capacity of the Ministry of Agriculture and Food to implement sector reforms, by developing a transparent legal framework for agricultural land markets, and by implementing reforms that attract irrigation system modernization investments. ARDS will improve agriculture sector competitiveness by supporting agricultural small and medium enterprises to introduce international quality and safety standards. ARDS will also support rural development by expanding employment and income opportunities and supporting target rural communities to develop viable economic strategies that stimulate economic growth.

In 2016, the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) and Ukraine signed the Country Programming Framework for Ukraine – an agreement which covers the period from 2016 to 2019. This agreement was prepared in consultation with the Ministry of Agrarian Policy and Food, representatives of other Ministries, professional business associations, science and civil society. It complements and supports Ukraine’s “Strategy for Agriculture and Rural Development 2015-2020.” The agreements is focused on four priorities: 1: business climate and setting up a stable legal framework – encompasses a broad range of activities, including market integration and access to markets but also support to the seed sector and capacity development for transboundary animal diseases; there will be an important focus on developing the legislative framework for organic food production and certification; 2: land reform and food security – FAO will support Ukraine’s land consolidation initiative, following the CFS’s Voluntary Guidelines on the Responsible Governance of Tenure of Land, Fisheries and Forests in the Context of National Food Security (VGGT); one objective is to support smallholders in acquiring farms with fewer parcels that are larger and better shaped to increase their competitiveness; 3: agri-food production chain development and access to international markets; and 4: environment and the management of natural resources. Land, water, forestry, fisheries, genetic resources and biodiversity are covered here. FAO is expected to contribute both technical and policy advice, with strong emphasis on climate change, forestry and land management (FAO, 2016).

In 2014, the World Bank started the “Capacity Development for Evidence-Based Land & Agricultural Policy Making” project. A part of this work includes Land Governance Monitoring in Ukraine. This is an innovative instrument for a comprehensive analysis of land market development as well as for making policy decisions in this field. Land Governance Monitoring is a system for collecting, storing and publishing the data and indicators on the state of land governance. The system supports analysis of the current state of land governance, drawing on more than 140 indicators. This set of indicators corresponds to the practice of other countries and recommendations by the World Bank (LGAF, 2013). It also includes indicators describing the progress of land reform in Ukraine. Implementation of the monitoring system is consistent with the principles recommended in the VGGT. These indicators cover all core functional areas of land governance, namely the coverage by registration in the State Land Cadastre and Registry of Rights to Immovable Property, the number and characteristics of transactions with land, land tax, disputes, privatization and expropriation, and equality of rights of different categories of landowners and land users. Also in 2015 World Bank started Rural Land Titling and Cadastre Development Project in Ukraine.

Several agribusiness firms from the EU and the US have also developed important investment projects in recent years. US-based companies ADM, Bunge, and Cargill (excluding Dreyfus) have invested billions of dollars in Ukraine recently, including in storage facilities and the sales of agricultural inputs. As industrial land for processing, storage, and transportation is not constrained by the same laws as farmland, foreign agribusinesses have invested heavily in these types of infrastructure.

The OECD project “Sector Competitiveness Strategy for Ukraine” was launched in 2009. During the initial phase, the project prioritized and defined sector-specific sources of competitiveness and policy barriers for improved investment promotion, particularly in the key sectors of agribusiness, machinery and transport equipment manufacturing, renewables and energy efficiency. The second phase of the project aimed to address specific policy barriers to focus on short-term results through practical and effective measures. The project is currently in Phase III, which aims to put in place the mechanisms for a sustainable reform process and support the Government of Ukraine in implementing them effectively. It does so by sharing OECD expertise and methodologies, identifying remaining policy challenges to private sector competitiveness in the target sectors, consulting closely with the private sector, and organizing capacity building events to strengthen government institutions. The project’s Phase III will conclude in December 2015, and is co-financed by the European Union and the Government of Sweden.

Freshwater (Lakes, Rivers, Groundwater)

RESOURCE QUANTITY, QUALITY, USE AND DISTRIBUTION

Ukraine has the richest water resources in Eastern Europe. The country can be divided into seven major river basins8, all of them discharging into the Black Sea, with the sole exception of the Western Bug which flows towards the Baltic Sea. Such basins include 1:the Dnipro basin, covering about 65 percent of the country, its main tributaries in Ukraine are the Desna river and the Pripyat river; 2: the Dniester basin, covering 12 percent of the country; 3:the Danube basin, covering 7 percent of the country.; 4: the Western Bug (Zakhidnyi Buh in Ukrainian) and San basins, covering 2 percent of the country.; 5: the Southern Bug (Pivdennyi Buh in Ukrainian) basin, covering 3 percent of the country, it is an internal river basin; 6: the Donets basin, covering 4 percent of the country; and 6: he coastal basin, covering 7 percent of the country, it groups all the small rivers that flow directly into the Sea of Azov and the Black Sea, including all the Crimean rivers.

The longest rivers within Ukraine are the Dnipro (1,121 km), Dniester (925 km), Southern Bug (806 km), Donets (700 km), Horyn (577 km), Desna (575 km), Inhulets (549 km), Psel (520 km), Sluch (451 km), Styr (424 km), Western Bug (401 km) and Orel (346 km) (Ukrstat, 2015a).

There are 12 big dams in the country, most in the east and south east. They are used primarily for irrigation and hydropower (FAO–AQUASTAT, 2015). There are also large man-made canals including the North Crimean Canal (400.4 km), Dnipro-Donbas Canal (550 km), Siversky Donets – Donbass Canal (131.6 km), and large irrigation systems (Kakhovska, Inguletska, etc). Ukraine has over 1,100 reservoirs with the total capacity of 55,500 million cubic meters (Guseva, 2012). Up to 43,700 million cubic meters are accumulated in the cascade of the Dnipro water reservoirs: the Kremenchug, the Kakhovka, the Kyiv, the Dnipro, the Kaniv and the Dniprodzerzhynsk. Other important dams are the Dniester dam in the Dniester river, the Krasno-Oskol dam in the Oskol river and the Simferopol dam in the Samir river. These dams are used for hydropower production, for supplying electricity to the main cities and industrial centers, for flood protection and for irrigation and fishery purposes.

From the dams the water is further redistributed by large canals, transporting water both within the same basin and from one basin to the other:

- The North Crimean Canal, built in 1961-1971, starts from the Kakhovka Reservoir near Nova Kakhovka and stretches for 400 km across the Northern Crimea and the Kerch Peninsula. The canal is designed to carry 380 m³/s of water. It provides irrigation to the area of more than 350,000 hectares;

- The Dnipro – Donbas Canal, built in 1969-1981, starts from the Dniprodzerzhynsk Reservoir and runs along the floodplains of the Orel and Orelka rivers to the Krasnopavlivka Reservoir, further to the Donets river near Izium. It brings water from the Dnipro river to the Donbas Region and the city of Kharkiv. In addition to municipal and industrial water supply, the canal provides water for irrigation. In 1979, it provided for the irrigation of 165,000 hectares;

- The Donets – Donbas Canal, commissioned in 1958, was designed to supply 25 m³/s of water;

- The Main Kakhovka Magistral Canal, constructed in 1980. It has a length of 130 km. It was constructed for irrigation and it’s also used for water supply to populated places;

- The Dnipro – Kryvyi Rih Canal, built in 1957-1961 and reconstructed in 1975-79, provides water for the industrial region of Kryvyi Rih. Water for the canal is collected at the Kakhovka reservoir and raised by a set of three pumping stations in order to reach the Pivdenne reservoir (the capacity of 57.3 million m³). The canal is used primarily for municipal and industrial water supply and also for irrigation on 26,000 hectares; and

- The Dnipro – Inhulets Canal runs from the Kremenchug reservoir to the Inhulets river. It has a length of 40 km and is used for irrigation and water supply

(FAO – AQUASTAT, 2015). Following the occupation of the Crimea by Russia, Ukraine stopped the fresh water supply of the peninsula through the North Crimea Canal.

There are approximately 3,000 natural lakes in Ukraine, with a total area of 2,000 km². The largest freshwater lakes are located in the central and southern parts of the country. In addition to these lakes, there are about 12,000 km² of swamps (peat soils) in the north. The lakes with the largest surface areas in the country are Yalpuh (149 km²), Kagul (90 km²), Kugurluy (82 km²), Sasyk (75 km²) and Katlabug (68 km²) (Ukrstat, 2015a).

Internal renewable groundwater resources are estimated at 22,000 million m³/year. Artesian wells are found at an average depth of 100-150 meters in the north of the country and at 500-600 meters in the south (FAO–AQUASTAT, 2015).

In 2016, 70 percent of Ukraine‘s water sources were from surface water and 30 percent were from groundwater. Industry generated the most withdrawals at 48 percent, whereas 30 percent went to irrigation and livestock and 22 percent to municipal use (Ukrstat, 2011).

Overall, 98.2 percent of the population in Ukraine use an improved source of drinking water – 98.6 percent in urban areas and 97.1 percent in rural areas. An improved sanitation facility is defined as the one that hygienically separates human excreta from human contact. Improved sanitation facilities for excreta disposal include flush or pour flush to a piped sewer system, septic tank, or pit latrine; ventilated improved pit latrine, pit latrine with slab, and use of a composting toilet. Almost the entire population of Ukraine (98 per cent) lives in households that have improved sanitation facilities (UNICEF, 2014). At the same time the water sector suffers from contamination as a result of the deterioration of the sewage system and agricultural wastes, and low sanitary and technical standards of the water supply system. 60 percent of existing water pipelines have been deteriorated and sanitary and technical conditions are unsatisfactory. The water supply infrastructure in the settlements mainly constructed in 1960s – 1970 needs systematic and large-scale renovation and reconstruction.

One key venue of opportunity for Ukrainian agriculture is better irrigation. Where mechanized irrigation equipment once stood in many Ukrainian fields, today, only irrigation infrastructure remains. During the Soviet era, irrigation was widely used throughout the country, not limited to the south as it is today. There were about 30 million hectares of arable land, 2.2 million hectares of which were irrigated. This irrigation infrastructure grew by approximately 100,000 hectares per year. Today, many elements of this irrigation infrastructure are still in place and functional with proper maintenance. While the irrigation machines from this era are now obsolete, much of the surviving infrastructure could theoretically be paired with new irrigation center pivots or linear (lateral move) machines and used once more (Aaron Schapper, 2015).

LEGAL FRAMEWORK

Although Ukraine has no comprehensive national water policy, there are over fifty laws and regulations related to the management and protection of Ukraine’s water resources and environmental issues. The most important of these is the Water Code of Ukraine dated 6 June 1995 (with the latest amendments in 2016; the “Water Code”), the Law of Ukraine “On Potable Water and Potable Water Supply” dated 10 January 2002 (the “Water Law”) and the Code of Ukraine on Subsoil dated 27 July 1994 (the “Subsoil Code”) regulating the use of subsoil water.

The Water Code declares that all water (water bodies) in the territory of Ukraine is the national endowment of Ukrainian people, and provides a natural basis for their economic development and social welfare. Ukrainian law restricts ownership of water bodies. In accordance with Article 51 of the Water Code, only the water bodies with a surface area of 3 hectares or less may be privately owned. All other water reservoirs are either state-owned or municipal. Private entities are entitled to lease them through public auctions. Ukrainian law is unclear whether lease of a water reservoir also requires parallel lease of the land plot underneath it. The practices vary region by region with some local authorities requiring mandatory execution of the land lease and payment of a land rent.

The Water Code provides for two types of water use – (i) general water use and (ii) special water use. General water use is reserved to the public for meeting their day-to-day needs, in particular, water supply without the use of specialized equipment, recreation, and fishing. It is free of charge and does not require receipt of any special permit. Special water is water intake from water bodies using specialized structures/facilities or equipment, in particular, use of water wells for extraction of subsoil water in public water supply, healthcare and agriculture. Both individuals and legal entities may engage in special water use subject to prior receipt of a permit.

The Water Law regulates water contamination, protection of drinking water, licensing of water use and water discharge, protection of water species and flood control. This Law recognizes water protection as a major element of environmental protection. It provides for the highest priority of preservation of drinking water, establishing state control over both groundwater and surface water. Management of water bodies varies depending on their hydrological parameters. The Water Law also restricts water contamination by defining protection and sanitary zones for potable water sources and imitating some economic activities within such sanitary and protection zones.

Multiple legislative orders, decrees, and regulations supplement the Water Code and the Water Law. The government’s primary goal is to implement the Water Framework Directive of the European Union (2000/60/EC). The scope of further works shall be focused on maintaining environmental value and functions of water resources; maintaining quality and quantity of water; ensuring access to safe potable water; and flood and drought-prevention activities.

TENURE ISSUES

All water bodies are the national endowment of the Ukrainian people. Thus, they are owned and controlled by the state. As mentioned above, private entities may have up to 3 hectares in ownership and lease water bodies from the appropriate state agencies.

Water use on the industrial scale will generally require receipt of a permit for the special water use from Region (Oblast) state administrations. Such permits set limits of water intake and disposal. Permit holders are to pay a special fee for both withdrawal of clean water and discharge of wastewater. Currently, the fee is UAH 15 (approximately, USD 0.57) per m3. Breach of the limits indicated in the permit is punishable with a fine calculated subject to overused m3 of water multiplied on defined rates. Water intake in excess of 300 cubic meters per 24 hours requires receipt of an additional permit for subsoil use. State control over the special use is largely based on the reports submitted by the permit holders and selectively checked by State Ecology Inspection which creates opportunities for corruption Permit holders are obliged to set automatic on-line connected counter equipment on water use. As a practical matter, this obligation is not widely fulfilled by permit holders, due to high cost of such equipment and political issues on the State Ecology Inspection. Since October 2016the Ministry of Ecology and Natural Resources of Ukraine (the “MENRU”) constantly declares the necessity to liquidate the State Ecology Inspection because of wide area for corruption. With support of USAID the MENRU plans to create a new Service of Environment Control instead of the State Ecology Inspection (MENRU, 26 October 2016).

In addition to the permits for the special water use, a special license is necessary for provision of the services of water supply and waste water removal. The issuance of this license is governed by the Law on Licensing dated 02 March 2015. The State Commission of State Regulation of Utility Services is in charge of issuing such licenses. Such licenses are issued for an indefinite period of time, with the sole exception of licenses for the water supply under a non-regulated rate. As a practical matter, licenses for water supply and waste water management are mainly issued to municipal companies which have the necessary costly infrastructure. Private companies are active only in the bottling and distribution of potable water which is less capital and labor intensive.

GOVERNMENT ADMINISTRATION AND INSITUTIONS

The most important authorizing bodies in the field of water resources management, use, protection and restoration are:

- The MENRU. The Ministry is responsible for environmental protection, restoration, protection and efficient use of water resources. The MENRU ensures legal and regulatory oversight of water management and land reclamation;

- The State Agency of Water Resources, supervised by the MENRU. The Agency is in charge of the implementation of government policies on water management and responsible for the management and use of surface water resources and for the off-farm irrigation and drainage systems;

- The State Committee for Water Management. The Committee was set up in 1998 as a specially empowered central executive body in the field of water management and implementation of the state policy on land-reclamation;

- Basin administrations are in charge of water resources management in the basin, design of political principles and plans for usage of water resources in the basin, and resolution of conflicts between users of water; and

- The State Hydro-meteorological Service is the agency responsible for weather forecasts, agrometeorological works and supervision, processing and distribution of hydro-meteorological information. It operates under the auspices of the State Emergency Service of Ukraine.

Other public agencies connected to water use are: The Ministry of Energy and Coal Mining Industry, the Ukrainian State Service of Sea and River Transportation, Ministry of Infrastructure, the State Ecology Inspection, the State Agency of Fishing Management, the Ministry of Health, the Ministry of Industry Policy, the Ministry of Agrarian Policy and Food and the Ministry of Regional Development, Construction and Housing. The effectiveness of these institutions is constrained due to their lack of basic tools to monitor compliance.

The system of state water management is based on the following registers:

- state register of water bodies;

- state register of subsoil water resources;

- state register of special water use holders;

- state register of issued permits on subsoil use.

GOVERNMENT REFORMS, INTERVENTIONS, AND INVESTMENTS