Overview

Around 97% of Papua New Guinea’s (PNG’s) land area is under legally recognized customary tenure. Both colonial and post-independence governments have adopted approaches to work with these systems, including the establishment of a legal process permitting customary groups to register titles to their land in their own name. Customary groups may also grant agricultural and business leases to the government for portions of their land. In some cases, the government has entered into agreements to acquire land rights from customary owners, compensated the owners, and then transferred the rights to private companies for mining or logging concessions.

In and around urban areas, migration and a growing volume of informal land transactions is threatening the rights of traditional customary groups. Increasing shortages of urban public land have also placed intense pressure on the government to issue new leases to private developers and evict residents of informal settlements, who account for a quarter of the population.

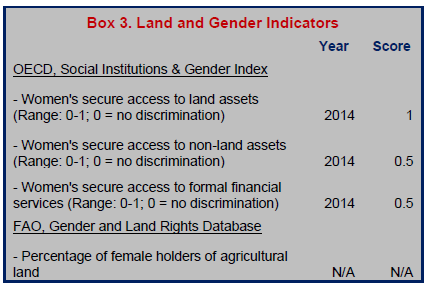

Women in rural communities have traditionally had access rights to customary land for subsistence purposes. However, such rights do not extend to decision-making powers over customary land. Women are typically deprived of an equal share of income from cash crops and of rental or compensation payments when customary land is leased out. They are also excluded from negotiations of lease arrangements.

Water is both a public asset and a public good in PNG, but the existence of customary rights over the resource is also recognized. Customary landowners exercise their rights to conduct traditional activities involving water, but this cannot be done to the exclusion of others. This applies to freshwater resources as well as coastal waters within three nautical miles of the coastline. The co-existence of public and customary rights has led to disagreements regarding the form and extent of compensation that developers (or other outsiders) should pay to customary rights holders when water resources are damaged or polluted.

Forestry-related provisions of the PNG legal and policy framework call for the informed consent of all landowners and provision of other benefits when the government acquires timber harvesting rights on customary land. However, the existence of customary rights has not guaranteed the protection of landowner interests. The large area of land required for a sustainable log export concession has made it difficult to secure the informed consent of all customary landowners associated with any given operation, often resulting in conflicts both before and after a Forest Management Agreement has been signed. Furthermore, the risk that some groups will lose most of their customary rights, including to land used for subsistence purposes, is even greater in areas under forest conversion concessions, some of which have been granted 99-year agricultural or business leases.

Legal and policy reforms in the mineral and hydrocarbon sectors have been hindered by ongoing debate over the PNG government’s legal claim to ownership of subsurface resources. Among the main reasons for the national government’s reluctance to acknowledge customary rights to subsurface resources is uncertainty surrounding the identification of customary landowners in areas covered by exploration and development licenses and disputes that have erupted between different groups of claimants. This issue is particularly problematic in the hydrocarbon sector where questions of who does or does not qualify as a customary landowner, compounded by claims by those with customary rights in adjacent areas and demands of migrant groups attracted by economic opportunities, have led to protracted disputes. In some cases, the national government has refused to distribute royalties and other benefits to customary owners.

Key Issues and Intervention Opportunities/Constraints

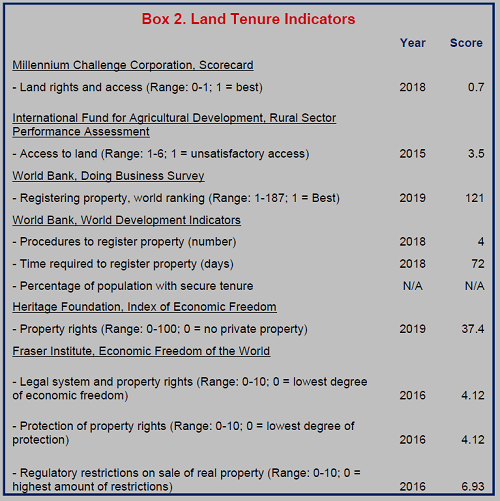

Recent legislative amendments and attempts to reform the institutions responsible for land administration and the settlement of land disputes have achieved little progress. Government plans to raise the proportion of land that is legally available in the “formal market” for “productive use,” from less than 5 percent in 2016 to 20 percent in 2022, have not advanced. Similarly, attempts to reduce the proportion of urban residents living in informal settlements to less than 15 percent by 2030 through the development of low-cost housing schemes have also stalled. In 2019, a National Land Summit called for a review of several elements of the National Land Development Program. Given the political sensitivity of land issues in PNG, the national government has been reluctant to seek donor assistance for advancing legal or policy reform. It has, however, been open to receiving technical assistance for planning, monitoring and evaluating specific programs.

The national government has a long-term plan to boost the proportion of rural households with access to electricity, and dams are expected to contribute more than 50 percent of future power supplies. A new water, sanitation and hygiene policy has also introduced a framework for financing the maintenance, rehabilitation and expansion of clean drinking water and sanitation service delivery, with a focus on rural villages and peri-urban settlements. Both of these initiatives will confront the tension between the legal definition of water as a public good and the legal recognition of customary use rights. Donors could provide technical support to government agencies and/or civil society organizations responsible for reconciling this apparent dichotomy.

While the National Forest Board stopped granting large-scale logging concessions some years ago, it has continued to grant forest conversion concessions to the developers of large-scale agricultural projects. The decision-making process for granting concessions has been far from transparent, and there is widespread public concern about the feasibility of the project proposals and the level of environmental damage resulting from the logging of native forests. Continued deforestation is also inconsistent with the government’s climate change policy framework. The government has shown some reluctance to accept donor support for a new round of policy reforms meant to clarify the relationship between concessions for forest clearance, forest conservation, and selective logging. Nonetheless, there are opportunities to provide technical assistance to relevant government agencies, including the PNG Forest Authority, to place more information about the decision-making process for concessions in the public domain.

Despite, and perhaps because of, a long history of donor support for protected areas, the national government has been reluctant to invest scarce financial resources from its own budget to establish a meaningful and sustainable network of protected areas. Following the completion of the current program funded by the Global Environment Facility, support will be needed to establish or maintain viable local organizations and institutions dedicated to the management of protected areas.

The national government is struggling to reform the laws and policies that apply to the extractive industry sectors and to comply with elements of the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative related to the distribution of benefits streams to local communities and subnational levels of government. Technical assistance directed to the negotiation and implementation of more equitable and sustainable benefit-sharing agreements is needed.

Summary

The area of land used (or disturbed) by humans in PNG is approximately 31 percent of the total surface area. Agriculture alone accounts for 25 percent, nearly all of which involves indigenous farming systems. Studies during the early 1990s found that the total area of land used for agriculture had expanded by less than 1 percent over 20 years, but the land in use was being cultivated more intensively. This often meant that the length of the fallow period was being reduced, especially in areas of high population density, since the area occupied by cash crops or tree plantations has remained fairly constant since 1975. The expansion of oil palm plantations (now half of all plantation land) has been offset by a reduction in the area planted with crops such as coconuts. With 97 percent of PNG’s land area under customary tenure, most rural people have access to land through their landowning clan membership though it is uncertain whether poor urban settlers have been able to maintain their rights. The shortage of land for subsistence agriculture has become a problem in regions with high population densities, or where customary land has been partially alienated for large-scale development projects. Even so, customary tenure systems generally provide all members of rural communities with land.

The total annual volume of renewable freshwater resources is estimated to be 170,000 cubic meters for each person in PNG. More than half the country’s rural households are thought to engage in some form of freshwater fishing activity; however, the total volume of annual production from inland fisheries has recently been estimated at only 20,000 tons. Groundwater resources have remained largely undeveloped, and very little irrigation is practiced. PNG has the lowest water access indicators in the Pacific Island region. In rural areas, less than one-third of the population has access to safe or improved drinking water. People are mainly reliant on natural surface-water sources. In urban areas, about 90 percent of people have access to treated and reticulated water, but only 60 percent of these get water piped directly into their homes. Pressure is greatest on the few water catchments directly feeding the major urban centers. These are subject to deterioration in water quality as unregulated human activities encroach on headwaters and upstream riverbanks. Urban freshwater sources are also at risk from pollution runoff or damage from industrial and resource-development projects.

The total annual volume of renewable freshwater resources is estimated to be 170,000 cubic meters for each person in PNG. More than half the country’s rural households are thought to engage in some form of freshwater fishing activity; however, the total volume of annual production from inland fisheries has recently been estimated at only 20,000 tons. Groundwater resources have remained largely undeveloped, and very little irrigation is practiced. PNG has the lowest water access indicators in the Pacific Island region. In rural areas, less than one-third of the population has access to safe or improved drinking water. People are mainly reliant on natural surface-water sources. In urban areas, about 90 percent of people have access to treated and reticulated water, but only 60 percent of these get water piped directly into their homes. Pressure is greatest on the few water catchments directly feeding the major urban centers. These are subject to deterioration in water quality as unregulated human activities encroach on headwaters and upstream riverbanks. Urban freshwater sources are also at risk from pollution runoff or damage from industrial and resource-development projects.

PNG has extensive native forest cover. However, by 2014 about 12 percent of the designated total forest area had been degraded by large-scale logging operations that started in 1975. The annual volume of raw log exports has mostly varied from 2 to 3 million cubic meters since the early 1990s, an estimate that was officially regarded as a sustainable level of harvest. The volume has recently reached a peak of nearly 4 million cubic meters. seemingly facilitated by a steady increase in the number of forest conversion concessions granted for large-scale agricultural projects over the past decade. The export of processed wood products is much smaller than that of raw logs, generally accounting for around 1 percent of the value of raw log exports. Fuelwood consumption averages around 1.8 cubic meters per person per annum (i.e., 15 million cubic meters for the entire population) and is mostly derived from the clearance of secondary forest fallows by local farmers.

Most of PNG’s landmass is covered by mining exploration or petroleum prospecting licenses. However, the development of these resources has mainly consisted of a few large-scale operations. The combined value of exports from the mining and petroleum sectors was worth around 78 percent of PNG’s average annual export earnings between 2000 and 2013. Crude oil accounted for 15 percent of total export earnings in 2013, gold reached 40 percent, copper 11 percent, and nickel plus cobalt 4 percent. By 2017, conditions had changed dramatically, with gas and condensate from the recently commissioned PNG Liquid Natural Gas Project accounting for 39 percent of total export earnings. The share of crude oil fell to 4 percent, gold to 24 percent, and copper to 6 percent; nickel plus cobalt rose to 6 percent. Declining production from existing oil fields is likely to be offset by the exploitation of new gas fields and a possible offshore oil project. One large-scale copper mine is expected to close within the next decade, but one or two new copper mines are expected to open. There are also plans for a coal mine and a deep-sea copper mine, despite questions about economic feasibility and strong opposition from environmentalists.

Land

LAND USE

The starting point for any assessment of land use in PNG is a dataset assembled by staff of the Australian Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation during the late colonial period. They undertook a variety of field surveys over a 20-year period (1953–1972) and inspected two sets of aerial photographs with national coverage. While their surveys covered most aspects of the physical environment, the main purpose of their work was to assess the potential for raising the productivity of the farming systems that sustained the majority of the indigenous population. In most of the publications associated with this dataset, 1975 is treated as the baseline year for the analysis of changes in the national landscape because this was the year in which PNG gained its independence from Australia. (Löffler 1977; Bleeker 1983; Bellamy and McAlpine 1995; Bleeker 1975; Hackett 1988; Trangmar et al. 1995)

The scientists involved in this exercise made a broad distinction between “used” and “unused” land, and then assigned the areas in use to seven different classes of “land use intensity” according to the extent of human disturbance that was evident in 1975. The total area of land in use (including urban areas) was 14.2 million hectares—about 31 percent of the total surface area—while the area used for some form of agriculture (excluding urban areas, grasslands and sago swamps) was 11.8 million hectares. Within the total area of cultivated land, less than 300,000 hectares was occupied by cash crops or tree plantations. That left 11.5 million hectares—about 25 percent of the total surface area—as the area used by indigenous farming systems. At any one time, most of this land was covered by secondary forest fallows created by the practice of shifting cultivation in forested areas. (Saunders 1993a; Allen and Bourke 2009)

Indigenous farming systems were subject to a further round of field surveys by another group of Australian scientists in the early 1990s. The main purpose of their work was to assess the capacity of these systems to sustain a rapidly growing rural population. They found that the total area of land used for cultivation had expanded by less than 1 percent over a period of 20 years, but the land in use was being cultivated more intensively, which sometimes meant that the length of the fallow period was being reduced, especially in areas of high population density.

Nevertheless, more than half of the land being cleared by indigenous farmers in 1996 was still ‘tall secondary forest’ fallows that had been regenerating for more than 15 years. The relationship between land use intensity and population density was also complicated by a number of environmental and economic factors that could have affected local variations in the incidence of land degradation. (Allen et al. 1995; Allen 2001; Allen et al. 2001; Hanson et al. 2001; Allen and Bourke 2009)

The area occupied by cash crops or tree plantations has remained fairly constant since 1975, mainly because the expansion of oil palm plantations, which now account for roughly half of all plantation land, has been offset by a contraction in the area planted to other cash crops, especially copra. Satellite imagery has not yet been used to measure the expansion of urban areas, but if the urban population is taken as a proxy for the urban land area, it would be reasonable to assume that the total area of urban settlement has grown from around 200,000 hectares to at least 800,000 hectares since 1975. (GPNG 2007a)

LAND DISTRIBUTION

It is commonly reported that 97 percent of PNG’s land area consists of customary land, while the remaining 3 percent is alienated (public or freehold) land. However, these proportions are derived from a government inquiry conducted in 1973, which found that land alienated during the colonial period covered 2.8 percent of the total land area. By 1988, the Department of Lands was only able to count about 600,000 hectares of alienated land in its filing system, which would suggest that the proportion of alienated land had fallen to 1.3 percent. (GPNG 2007b; AusAID 2008; Filer 2014)

It is also commonly asserted that all indigenous citizens have access to customary land by virtue of their membership in landowning clans. However, it is uncertain whether urban residents, especially poor people living in squatter settlements, have retained their rights to customary land in the rural areas where they were born. (GPNG 2008; ADB 2002)

It is also commonly asserted that all indigenous citizens have access to customary land by virtue of their membership in landowning clans. However, it is uncertain whether urban residents, especially poor people living in squatter settlements, have retained their rights to customary land in the rural areas where they were born. (GPNG 2008; ADB 2002)

There are no published statistics on the distribution of customary land rights between groups of people living in rural areas, but it is generally assumed that systems of customary tenure provide all members of rural communities with access to enough land to feed themselves. However, the shortage of land for subsistence agriculture has become a problem in areas with very high population densities or in areas where customary land has been partially alienated for large-scale development projects. (Filer et al. 2017; Hanson et al. 2001; Kalinoe and Kiris 2010; Mousseau 2013; Global Witness 2014; Gabriel et al. 2017)

LEGAL FRAMEWORK

There is one body of law that applies exclusively to alienated land, a second that applies to customary land, and a third that applies to the movement of land between these two general categories. The first body of law was largely inherited from the Australian colonial administration, and therefore resembles the current Australian legal framework. The second body of law was largely created around the time of Independence but has been modified in various ways since then. The third body of law contains a mixture of colonial and post-colonial provisions. (James 1985)

Although the current version of the Land Act dates to 1996, most of its provisions are part of PNG’s colonial legacy and apply to land that was alienated during the colonial period. The Land Registration Act of 1981 is also rooted in PNG’s colonial legacy and provides for the registration of titles to alienated land. It should not be confused with the National Land Registration Act of 1977, which was intended to compensate customary landowners (or their descendants) for previous acts of alienation that were deemed to have been unreasonable or unfair.

The Land (Tenure Conversion) Act of 1963 is all that remains of the colonial government’s various efforts to mobilize customary land for development purposes without buying it from the customary owners. This law enables customary groups, or clans, to transform their land into a collection of registered freehold titles and distribute these amongst their individual members. Hardly any use has ever been made of it and the National Land Development Taskforce recommended that it be repealed. This recommendation has not been implemented. (GPNG 2007b)

The colonial government’s other attempts to create registered titles over customary land were firmly rejected by a commission of inquiry established at the time of self-government in 1973. Indigenous politicians preferred a legal mechanism that would enable customary groups, once they acquired legal personality, to decide on the development of their land without enabling them to permanently alienate their collective customary rights. This was the rationale for the Land Groups Incorporation Act of 1974. (Sack 1974; Ward 1983; Fingleton 1982; Power 2008)

The commission of inquiry recommended the adoption of an additional legal mechanism that would enable incorporated land groups to register their collective titles and thus be able to lease (but not sell) their land to their own clan members or to third parties. This was largely achieved through amendments to the Land Act that enable incorporated land groups to lease portions of land to the government on condition that these portions are then leased back to the groups themselves or else to landowner companies with which they are associated. This “lease-leaseback” scheme was a roundabout way of creating registered titles over what was still recognized as customary land. (Filer 2014)

In 2009, amendments to the Land Groups Incorporation Act and the Land Registration Act finally made provision for incorporated land groups to register titles to their own land, with a number of provisions designed to improve the level of transparency and accountability in the process of incorporation. These amendments came into effect in 2012. Thousands of incorporated land groups already established under the original legislation were given five years in which to reincorporate themselves under the amended legislation, regardless of if they were seeking to register titles to their land. The grace period has since been extended for another five years. The new legislation appeared to remove the rationale for the lease-leaseback scheme, but the clauses of the Land Act providing for these leasing arrangements have not yet been repealed.

TENURE TYPES

Freehold titles are said to cover 230,000 hectares of land in PNG, but that assumes that 3 percent of the total land area has been alienated. Most of these titles were established under the German administration of Papua New Guinea, before the First World War, and then preserved by the Australian administration that succeeded it. The National Constitution of 1975 says that freehold titles can only be sold to citizens of the independent state, and the Land (Ownership of Freeholds) Act of 1976 takes this to mean that they can only be sold to government agencies, incorporated land groups or customary business groups, and not to private companies. The result has been a steady decline in the extent of freehold titles, as some of the holders (especially churches) have surrendered them to the government. (AusAID 2008)

The Australian colonial administration preferred to keep all alienated land in public ownership and grant leases to individuals or companies for specific purposes and periods. This preference has been retained since Independence. However, there is a widespread belief that alienated land reverts to customary ownership when such leases expire. Although this belief does not accord with the law, it may help to explain why the total area of alienated land appears to have been shrinking. (Filer 2014)

Like leases provided on public land, the special agricultural and business leases (SABLs) granted under the lease-leaseback scheme have mostly been for the maximum allowable period of 99 years. By 2011, more than 5 million hectares of customary land (11 percent of the total land area) had been covered by such leases, and the national government responded to public pressure by setting up a commission of inquiry to assess the extent to which the customary owners had freely consented to the reduction of their customary rights. The findings of this inquiry persuaded the government to impose a moratorium on the grant of such leases, and several of the larger ones have since been cancelled or revoked (Filer 2017; Filer and Numapo 2017).

The government also grants other types of lease or license over customary land for specific types of resource development, such as mining or logging concessions, by means of sector-specific agreements with the customary owners or their representatives. These agreements normally last for periods of between 10 and 50 years and provide for various forms of compensation to be paid in return for the rights that are acquired by the government and then transferred to private companies. The area covered by agreements of this kind is currently in excess of 7 million hectares (15 percent of the total land area).

Official notices published in the National Gazette indicate that incorporated land groups had managed to register titles for approximately 233,000 hectares of land by the end of 2018, taking advantage of the opportunity provided by amendments to the Land Groups Incorporation Act and the Land Registration Act. This is much lower than the level anticipated by the architects of the legislation.

SECURING LAND RIGHTS

The national government has been consistently opposed to the systematic registration of customary land rights, partly as a matter of principle and partly because it lacks the resources to undertake such an exercise. Although it has now made provision for the voluntary sporadic registration of group titles, this innovation has been opposed by people who believe that it creates new opportunities for theft or fraud, and hence for some customary landowners to be deprived of their customary rights. Their views were confirmed by the commission of inquiry into special agricultural and business leases, which found that land group executives and landowner company directors could not be trusted to represent the interests of the larger population that they claimed to represent. The same finding had been made by an earlier commission of inquiry into corruption in the forestry sector. (Anderson and Lee 2010; Mirou 2013; Numapo 2013; Barnett 1992)

Supporters of the legislation allowing for registration of group titles argue that the potential for fraud should be solved by reforming the institutions that oversee land administration. Their concern has been to tackle the insecurity that arises from the growing volume of informal land transactions, especially in urban and peri-urban areas, between customary landowners and settlers from other parts of the country. On one hand, the informal sale of customary land to these migrant households does not provide them with any legal protection against subsequent eviction. On the other hand, when such transactions are undertaken by individual members of customary groups without the consent of other members, there is the potential for the group’s customary rights to be extinguished if migrant settlements become extensive. Anecdotal evidence from the national newspapers and other sources suggests that this second outcome is now quite widespread in Port Moresby, the national capital, where the migrant population is especially large. (GPNG 2007b; Koczberski et al. 2009; Yala et al. 2010; Numbasa and Koczberski 2012)

Migrants living in settlements located on what had previously been vacant public land now account for as much as a quarter of the urban population. Some have sought to secure their rights PAPUA of occupation by making informal payments to people claiming customary rights over that land. In the meantime, the growing shortage of public land in major urban areas, especially in the national capital and the secondary city of Lae, has created a situation in which the government is under intense pressure to issue new leases to private developers. An alliance between migrant settlers and customary landowners does not guarantee that the former will not be evicted sooner or later. (Chand and Yala 2008; Rooney 2017)

INTRA-HOUSEHOLD RIGHTS TO LAND AND GENDER DIFFERENCES

Women are not subject to any legal disadvantage or discrimination in the ownership or transmission of rights to alienated land. Gender equity or equality is far more problematic in the distribution of rights to customary land.

A distinction is commonly drawn between patrilineal, matrilineal, and cognatic kinship systems, depending on whether membership of the customary landowning group is inherited through the paternal line, the maternal line, or some combination of the two. Matrilineal kinship systems are mostly confined to the islands east of the mainland. (Filer et al. 2017)

A distinction is commonly drawn between patrilineal, matrilineal, and cognatic kinship systems, depending on whether membership of the customary landowning group is inherited through the paternal line, the maternal line, or some combination of the two. Matrilineal kinship systems are mostly confined to the islands east of the mainland. (Filer et al. 2017)

Regardless of the kinship system, women in all rural communities have traditionally had access to some portions of customary land for subsistence purposes. However, such use rights do not provide women with decision-making powers over the disposition of a group’s land. When customary land is planted to cash crops, men generally control the distribution of the income, even though women contribute more than 50 percent of the labor required for their cultivation.

Likewise, when customary land is leased to private companies for some form of large-scale resource development, men generally control the negotiation of the lease arrangements, as well as the distribution of rental or compensation payments (Andrew 2013; GPNG 2007a; World Bank 2012).

The recently amended version of the Land Groups Incorporation Act requires that there be at least two women elected as members of a group’s management committee before the group can be registered. This provision is indicative of a tendency to exclude women from such roles in the absence of directives from the government and is unlikely to prevent male clan leaders from exerting their dominance over decisions about customary land (GPNG 2008; World Bank 2012).

LAND ADMINISTRATION AND INSTITUTIONS

The regulation of dealings in alienated land is vested in the Department of Lands and Physical Planning, which administers the Land Act, the Land Registration Act, and the Physical Planning Act. The Land Act provides for the establishment of a National Land Board that advises the minister on the grant of leases on state land. The Physical Planning Act provides for the establishment of a National Physical Planning Board that is meant to provide related advice on the most appropriate uses of state land. The functions of both boards may be delegated to their provincial counterparts, but only some of PNG’s 22 provinces have established such bodies. The land boards are frequently accused of corruption or incompetence in their management of the leasing process, while the planning boards have generally been unable to produce development plans that can serve as a check on the activities of individual politicians and their business partners. The perceived failures of development planning in the larger urban centers, especially the national capital, led to the establishment of a separate Office of Urbanization in 2004. However, this body was subsequently abolished. (Alaluku 2010)

A separate branch of the Lands Department is responsible for administration of the Land Groups Incorporation Act, and hence for managing the process by which land groups apply for incorporation. This branch has never had the resources that would be required to prevent the registration of what are commonly known as “bogus” land groups. Recent amendments to the Land Groups Incorporation Act and the Land Registration Act have substantially added to the workload of this branch. However, inconsistencies between notices published in the National Gazette, which are now meant to record the different stages in the process by which group titles are eventually registered, suggest that the branch still lacks the resources needed for the task. (Antonio et al. 2010)

There have been several attempts to digitize the records held by the Lands Department, but none have produced the desired result. Documents relating to land titles have been stored in filing cabinets, files have frequently disappeared, land survey maps have not been properly updated, and information has not been shared between the different branches of the department. The loss of official records may partly explain the apparent shrinkage in the total area of alienated land since 1975. It also helps to explain how some pieces of land can end up being covered by more than one title. (GPNG 2007b)

Administration of the Land (Tenure Conversion) Act is vested in the Land Titles Commission, which is a quasi-judicial body established under the Land Titles Commission Act of 1962 and located in the Department of Justice, not the Department of Lands. This body was originally established in 1962 with a mandate to survey customary land boundaries and settle disputes between the customary groups claiming ownership of it. It was largely deprived of these functions in 1975 and has since lacked the institutional capacity to process applications for tenure conversion. (GPNG 2007b)

LAND MARKETS AND INVESTMENTS

The formal or legal land market is constrained by the small volume of land that is covered by transferrable titles. This is reflected in the very high rents paid for land or housing in urban areas, which has made it very difficult for most citizens to afford the cost of buying their own home on a portion of alienated land. This problem is compounded by the unwillingness of the banks to provide mortgages for periods longer than a few years because of what they consider to be the high risk of default. The registration of customary group titles under the recently amended version of the Land Registration Act has not solved this problem because the law does not allow the underlying title to be alienated from the group. Instead, customary groups seeking financing to develop their land must enter into a partnership with a company that is willing and able to finance development of the land. The same constraint has been faced by land groups or landowner companies that obtained “special agricultural and business leases” under the lease-leaseback scheme. Such leases have only been marketable assets in the sense that their holders could sub-lease the land to a developer, often on terms that provide very little benefit to the customary owners. (GPNG 2010a; Rooney 2017; Mirou 2013; Numapo 2013)

From the point of view of investors or developers, PNG’s land market has been distorted in three different ways. First, the perceived corruption and incompetence of the Lands Department and the land boards poses a risk to the security of any lease granted by the minister, especially when several investors are competing for access to the same portion of land. Secondly, even when an investor has secured a title over a portion of alienated land, access to the land may be held up by the presence of informal settlers who demand to be compensated for their eviction. Finally, the descendants of the customary owners may well make their own demands for compensation, even if they are not occupying the land, on the grounds that it was not properly alienated in the first place. All of these eventualities are liable to trigger court proceedings, sometimes with encouragement from local politicians. (Filer 2014)

COMPULSORY ACQUISITION OF PRIVATE PROPERTY RIGHTS BY GOVERNMENT

Although the Land Act of 1996 and the Lands Acquisition (Development Purposes) Act of 1974 both make provision for compulsory acquisition of customary land for public purposes, the government has mostly steered away from exercising these powers. Provisions for compensation are contained in the Valuation Act of 1967, and the benchmark for compensation is a “price schedule” published by the Office of the Valuer-General in the Lands Department, but landowners are rarely inclined to accept these prices. Their resistance, and the government’s reluctance, are both justified by a clause in the National Constitution that guarantees “protection from unjust deprivation of property.” (Manning and Hughes 2008; GPNG 1975a at art. 53)

The threat of protracted litigation has made the government generally reluctant to exercise its power of compulsory acquisition over the remaining freehold titles, or even to revoke leases granted over public land if the holders fail to develop it.

LAND DISPUTES AND CONFLICT

While court records show that disputes over alienated land are focused mainly on the legality of the titles issued by the Lands Department, there is no systematic evidence relating to the prevalence and causes of disputes over customary land. This is because most of the institutions responsible for resolution of disputes on customary land do not keep written records. Anecdotal evidence suggests that such disputes are mainly due to: the growing scarcity of arable land in rural areas with high population densities, the transfer of use rights to private developers without the prior consent of all the customary owners, and the prospect of compensation or benefits to be derived from some form of large-scale resource development.

Disputes over customary land are meant to be resolved by a set of institutions established by the Land Disputes Settlement Act of 1975. The first of these institutions is a process of mediation undertaken by a government-appointed “land mediator” who is responsible for dealing with such disputes in a small number of villages or local council wards. If mediation fails, the case may be taken to a Local Land Court where it will be adjudicated by a land court magistrate and a number of land mediators from the same district. A decision of the Local Land Court may be appealed to a Provincial Land Court, or even to other parts of the judicial system.

The national government has referred a number of intractable land disputes associated with the development of major resource projects to the Land Titles Commission, which is the body that was responsible for settling disputes over customary land before the passage of the Land Disputes Settlement Act, and has since been given the narrower task of deciding whether a piece of land is customary or not. Judgments made by this body can be appealed to the National Court or the Supreme Court, which are the bodies responsible for settling disputes about the ownership and use of alienated land. As a result, some disputes about the ownership of customary land have been circulating between different parts of the judicial system for many years without being finally settled. (Kalinoe 2010)

The National Land Commission is a separate body that is also housed in the Department of Justice. It was established by the National Land Registration Act of 1977 and is part of the post-colonial institutional architecture. The commission is responsible for settling disputes about whether customary landowners were fairly compensated for the alienation of customary land during the colonial period. This body has been frequently criticized and sometimes suspended because of the generous awards made to some of the claimants. (Kalinoe 2004; Power and Tolopa 2009)

The land courts and the two land commissions have not had the resources to deal with the constant increase in the volume of disputes over customary land. In some parts of the country, land mediators have ceased to perform any role in dispute settlement, either because the work is too dangerous or because they have not been paid for their services. Recommendations have been made for the land courts and the two land commissions to be merged into a single body by means of amendments to the relevant legislation, but these have yet to be implemented. (Oliver and Fingleton 2008; Allen and Monson 2014; GPNG 2007b; Duncan 2018)

GOVERNMENT REFORMS, INTERVENTIONS AND INVESTMENTS

The most recent wave of government reforms was initiated by a National Land Summit convened in 2005. This led to the formation of a National Land Development Taskforce that made numerous recommendations under three broad headings. The first group of recommendations led to the amendments subsequently made to the Land Groups Incorporation Act and the Land Registration Act. These were intended to create a legal avenue for the establishment of formal group titles to large areas of customary land, and thus to diminish what one government policy document has described as a “mountain of dead capital.” However, it was recognized that this goal would not be achieved without additional action to reform the institutions responsible for land administration and the settlement of land disputes. This recognition prompted the design of a National Land Development Program whose first phase was to be implemented over a five-year period from 2011 to 2015. Although some innovations were made during that period, many of the recommendations of the taskforce have fallen by the wayside, and there is no evidence that the program has entered a second phase. A second National Land Summit was convened in 2019 in order to reinvigorate the reform process (Yala 2010; GPNG 2007b; GPNG 2008; GPNG 2014a at xvi; GPNG 2010b; Duncan 2018; GPNG 2019a).

The most recent of the national government’s medium-term (five-year) development plans is still calling for a “legal unlocking of land for productive use,” and aims to raise the proportion of bankable land in the formal market from less than 5 percent in 2016 to 20 percent in 2022. The category of bankable land appears to refer to the combination of: (1) land alienated during the colonial period; (2) the area covered by special agricultural and business leases that had not been revoked by the courts or cancelled by executive orders; and (3) the titles formally registered as the properties of incorporated land groups by 2016. Given that a moratorium was effectively placed on the grant of new SABLs under the lease-leaseback scheme in 2011, when the commission of inquiry was established, and the government’s reluctance to exercise the power of compulsory acquisition, it is hard to imagine how the target can possibly be reached. The area covered by registered group titles does not appear to be growing by more than 50,000 hectares a year. (GPNG 2018 at 25-26)

The national government’s long-term (20-year) plan aims to reduce the proportion of the urban population living in informal settlements from 28 percent in 2008 to less than 15 percent in 2030 (GPNG 2010a: 85). In pursuit of this goal, the government has issued many urban development leases over public land for the construction of low-cost housing schemes, especially in the national capital. However, these have been subject to numerous public complaints and even the prosecution of a former member of parliament and some senior government officials for fraudulent dealings in the land titles. (GPNG 2010a; Wani 2019)

DONOR INTERVENTIONS

The Australian aid program provided financial support for the National Land Summit held in 2005, and for the subsequent work of the National Land Development Taskforce. However, donor-funded consultants did not participate in these activities because national stakeholders wanted to ensure that the outcomes could not be represented as a foreign attack on customary land rights, as had happened with earlier attempts at land reform in the 1990s. (Levantis and Yala 2008)

The Australian aid program funded a team of consultants to design the first phase of the National Land Development Program, and then provided financial support to the National Research Institute, a government think-tank, to monitor and evaluate its implementation. In 2018, the lands minister announced that the Australian aid program would also fund a technical adviser to conduct an audit of the Lands Department and recommend measures for its modernization. This kind of technical assistance has been provided at regular intervals since Independence, but the results have been disappointing (GPNG 2010b; Duncan 2018; Anon 2018).

Freshwater (Lakes, Rivers, Groundwater)

RESOURCE QUANTITY, QUALITY, USE AND DISTRIBUTION

The climate in PNG is generally humid and rainy, with alternating wet and dry (or less wet) seasons in most parts of the country. On the mainland, the mean annual rainfall ranges from less than 2,000 mm along the coast, to more than 8,000 mm in some mountain areas, while the islands to the north and east of the mainland receive an average of between 3,000 and 7,000 mm. The coastal zone around the national capital is the driest part of the country, with less than 1,000 mm. The whole country is subject to periodic droughts associated with the El Niño Southern Oscillation, the last of which occurred in 2015. Climate change is expected to result in small increases in average annual rainfall across the country by 2030 and may contribute to the frequency or intensity of the droughts. (McAlpine and Keig 1983; Allen and Bourke 2009; Bourke et al. 2016; Bourke 2018)

The presence of high mountain ranges and abundant rainfall leads to substantial runoff over most of the country. The total annual volume of renewable freshwater resources is estimated to be approximately 800 billion liters, or 170,000 cubic meters for each human resident. Inland water bodies cover about 1 million hectares, or 2 percent of the country’s total surface area. These include 5,383 freshwater lakes and 14 major rivers. Five of the major rivers (all on the mainland) have catchments exceeding 1 million hectares, and these are the only rivers that are navigable for any considerable distance from the coast. Only 22 of the lakes have a surface area of more than 1,000 hectares. (World Bank 2019a; GPNG 2014a; CIA 2019; FAO 2011)

The larger river systems on the mainland provide most of the inland fisheries harvest. Indigenous fish species have generally low levels of productivity, and are now much less common, since several exotic species have been introduced to supplement the availability of protein for the human population. More than half of the country’s rural households are thought to engage in some form of freshwater fishing activity, even in the central highlands, where fish stocks are poor. However, this is mostly a part-time subsistence activity using fairly rudimentary technologies. The total volume of annual production from inland fisheries has recently been estimated at 20,000 tonnes, but the commercial catch of wild fish does not amount to more than 10 tonnes, while fish farms account for roughly 150 tonnes. (Werry 1998; FAO 2017; Gillett 2016)

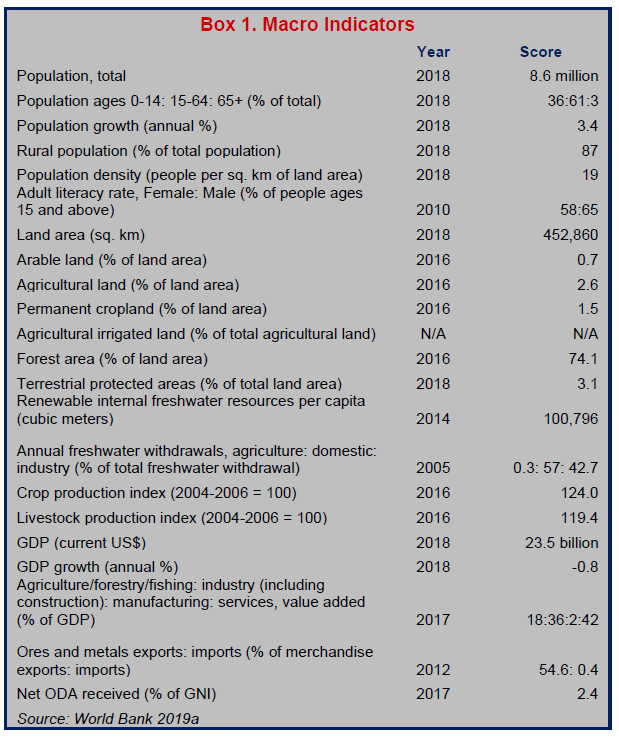

Although smallholder agriculture is the most common and widespread economic activity in PNG, there is very little irrigation, techniques are rudimentary, and irrigated gardens areas are generally small. Domestic and industrial consumption, therefore, account for almost all freshwater withdrawals (Box 1). As the country has abundant surface water assets and there are few large-scale consumers, groundwater resources have largely remained undeveloped, though they do provide an important source of reliable high-quality water for many villages and several major towns. (Water PNG 2018)

PNG has the lowest water access indicators in the Pacific Island region. In rural areas, less than one-third of the population has access to a safe or improved drinking water source, whether public standpipes, boreholes, protected wells, or springs. Most rural people are reliant on surface water from streams, rivers, lakes, ponds, reservoirs, estuaries, and swamps. In urban areas, about 90 percent of people have access to treated and piped water, but only 60 percent of these get water piped directly into their homes. Demand for water has grown rapidly in major urban centers, putting pressure on the few water catchments directly accessible to them. Meanwhile, the expansion of urban informal settlements in sensitive locations, such as headwaters and upstream riverbanks together with unregulated agricultural and waste disposal practices are contributing to deteriorating water quality. (SOPAC 2007; GPNG 2014a; CIA 2019; UTS 2011; Water PNG 2016; WHO and UNICEF 2017)

Hydropower plants supply electricity to Port Moresby and some of PNG’s other major towns. The plant that supplies the national capital was commissioned during the colonial period and its reservoir also provides most of the city’s current water supply. However, the plant is no longer capable of meeting the needs of a rapidly growing population. A somewhat larger hydropower plant was commissioned in 1991 and currently supplies electricity to the second largest city (Lae) and several other towns in the central part of the mainland. Hydropower now accounts for roughly 40 percent of electricity supply from all sources. (OBG 2017)

LEGAL FRAMEWORK

The legal protection of PNG’s freshwater resources is primarily contained in provisions of the Environment Act of 2000. This is the legislation under which “environment permits” are granted for various forms of natural resource extraction or industrial development. Where these permits allow for the pollution of rivers, lakes or other water bodies, the holders are required to minimize such damage and to provide water quality data to the government to demonstrate their compliance with the conditions attached to the permits.

The national government’s own responsibilities for the protection of drinking water quality are set out in the Public Health Act of 1973.

The Fisheries Management Act of 1998 includes provisions for the regulation of inland as well as coastal fisheries, and for the development of specific management plans that are formulated as separate regulations under the Act. The only freshwater fishery that has so far been subject to such a regulation is the Barramundi fishery in Western Province. (GPNG 2004)

TENURE ISSUES

While the Environment Act treats water as a public good that is owned by the state, it also recognizes the existence of customary rights to the use of rivers, lakes and other sources of freshwater, in line with the provisions of the National Constitution of 1975 and the earlier Customs Recognition Act of 1963. This means, in effect, that customary landowners can exercise their own rights to conduct traditional activities that involve the use of water, such as navigation or fishing, but not to exclude other users. This co-existence of public and customary rights is generally understood to extend to coastal waters within three nautical miles of a coastline and is recognized in the management plans formulated under the terms of the Fisheries Management Act.

People’s conception of their customary rights to water resources are sometimes at odds with the government’s conception of the public interest. The main bone of legal contention has been the form and extent of the compensation that developers or other outsiders should pay to the holders of customary rights when water resources are polluted. (Hyndman 1993; Shug 1994; Asafu-Adjaye 2000; Kalinoe 1999; Filer and Kalim 2003)

GOVERNMENT ADMINISTRATION AND INSTITUTIONS

The Conservation and Environment Protection Authority (CEPA) is responsible for administration of the Environment Act. Environmental permits for activities that involve a significant risk of water pollution are issued by the minister based on the environmental impact assessments provided by the applicants. CEPA has the power to investigate subsequent public complaints about pollution, but the cost of the investigation is typically borne by the permit holder, which can be seen to compromise the results. (Filer and Kalim 2003; SOPAC 2007)

The Geological Survey Division of the Mineral Resources Authority provides separate advice to mining companies on groundwater exploration, assessment, management, and protection.

There are two state-owned enterprises responsible for water delivery to industrial and domestic consumers. Eda Ranu, which supplies the national capital, was established under the terms of the National Capital District Water Supply and Sanitation Act of 1996. Water PNG, which supplies the rest of the country, operates under the terms of the National Water Supply and Sanitation Act of 2016, which replaced the National Water Supply and Sewerage Act of 1986. Responsibility for the development and management of rural water supplies is shared between Water PNG and the Department of Health. The Department of Health is also responsible for ensuring the quality of drinking water in urban areas according to the terms of the Public Health Act. (Water PNG 2018)

The Fisheries Management Act is administered by the National Fisheries Authority (NFA), whose board includes representatives from the fishing industry and civil society. The Act does not allow for provincial or other local government entities to play a regulatory role except at the discretion of the minister. The NFA is largely concerned with the regulation of coastal and deep ocean fisheries. The Barramundi fishery is the only inland fishery that is actively regulated. (FAO 2017; Smith 2007)

Management of the country’s electricity supply, including hydropower plants, is vested in another state-owned enterprise, PNG Power Ltd.

GOVERNMENT REFORMS, INTERVENTIONS AND INVESTMENTS

Water pollution is flagged as a major environmental concern in the national government’s long-term (20-year) development plan, with a national pollution market offered as a possible solution to the problem. This idea may have been inspired by talk of a forest carbon market. No further steps have been taken to develop a water pollution market. (GPNG 2010a at 117)

The government’s current goal is to increase the proportion of households with access to clean drinking water from 33 percent in 2016 to 50 percent in 2022, 70 percent in 2030, and 100 percent in 2050. A new water, sanitation and hygiene policy introduced a framework for financing the maintenance, rehabilitation and expansion of water and sanitation service delivery, with a primary focus on rural areas and peri-urban settlements. Concerns about the lack of government coordination and commitment in the water sector have led to a current proposal to merge Eda Ranu and Water PNG into a new statutory body to be called the Water, Sanitation and Hygiene Authority. (GPNG 2009a; GPNG 2010a; GPNG 2015b; GPNG 2018).

The government has identified the development of inland aquaculture as a strategic priority, and the NFA has identified a number of measures that could be taken to achieve this goal. (GPNG 2009a; GPNG 2014b; FAO 2017)

The government’s long-term development plan aimed to increase the proportion of rural households with electricity from less than 4 percent in 2010, to more than 60 percent in 2030. It also expected that dams would contribute 52 percent of PNG’s electricity supply by 2030, which would be more than twice the volume generated from other renewable resources. However, it was acknowledged that big dams would require massive private investment, while a stated preference for mini-hydro schemes might not be sufficient to meet the target. Four major hydropower projects have been under active consideration by the government during the past decade. Two of these would create additional electricity supply to the national capital, while a third would complement the existing plant that supplies the central part of the mainland. (GPNG 2010a)

DONOR INTERVENTIONS AND INVESTMENTS

The European Commission financed a rural water supply and sanitation program that was completed in 2012. This program sought to establish community ownership and responsibility for the maintenance of new facilities in all rural areas. Implementation was facilitated by several business enterprises and a variety of civil society and community-based organizations. Nevertheless, in 2013 water and sanitation access rates were expected to decline over the period of 2010 to 2030. The World Bank has supported improvements in the planning and implementation capacity of national water sector institutions and increased access to water supplies in selected urban centers and rural districts through its US$70 million water supply and sanitation development project, which was approved in 2017. Other donors, including the World Health Organization, UNICEF, the Asian Development Bank, and the Australian government, have contributed to the improvement of water supplies in specific parts of the country. Much of this additional support has been channeled through non-governmental organizations (NGOs) such as World Vision, Plan International, Oxfam Australia and WaterAid PNG. (World Bank 2014; World Bank 2015a; World Bank 2017a)

The Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research has been providing technical support for the NFA’s Inland Aquaculture Research Project since 2015. This project has sought to evaluate the socio-economic impacts of fish farming, improve fish husbandry technologies, and develop low-cost feeding and fertilizer strategies.

The World Bank has provided technical support to develop policy and planning capacities in the renewable energy sector through an energy sector development project that began in 2013. This project has included support to produce feasibility and impact studies for one of the two new hydropower projects that are meant to create additional power supplies for the national capital. The Asian Development Bank is currently supporting construction of a smaller run-of- river hydropower plant in the Autonomous Region of Bougainville as part of the second stage of a town electrification investment program. (World Bank 2015b; PNG Power 2019)

At the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation meeting held in Port Moresby in 2018, the governments of Australia, Japan, New Zealand and the United States undertook a commitment to provide support for the government’s efforts to achieve its long-term goal of providing electricity to 70 percent of the population by 2030. To this end, the World Bank also has plans to provide further assistance. The construction of additional hydropower facilities is expected to play a significant role in the achievement of this goal. (World Bank 2017b)

Trees and Forests

RESOURCE QUANTITY, QUALITY, USE AND DISTRIBUTION

At the time of Independence, members of an Australian scientific team completed a basic classification and mapping of the different types of native forest found in PNG. More recent assessments have been based on satellite imagery captured in 1996, 2002 and 2014. Debates about the extent of deforestation and forest degradation since 1975, have focused on five issues: (1) the distinction between “primary” and “secondary” native forests; (2) the extent of forest cover in the 1972–75 baseline period; (3) the reliability of satellite imagery as evidence of degradation versus deforestation; (4) the degree to which logging, subsistence farming, or other drivers have been responsible for degradation and deforestation; and (5) the extent to which native forests have been capable of regeneration after these different kinds of disturbances. (Saunders 1993b; Hammermaster and Saunders 1995; Buchanan et al. 2008; Shearman et al. 2008; Filer et al. 2009; Filer 2010; Fox et al. 2011; Hoover et al. 2017; Babon and Gowae 2013)

Some observers define PNG’s forests as areas in which most of the trees have overlapping crowns, thus excluding some areas of woodland that would be counted as forests under common international standards. That is because PNG has extensive native forest cover, even by this narrower definition. The Australian scientists responsible for the creation of the 1975 baseline mapping designated 33.7 million hectares as gross forest area, of which 28 million hectares showed no sign of human disturbance. The remainder consisted of tall secondary forest associated with low intensity shifting cultivation. This definition was meant to establish the outer limits of the area that might be suitable for large-scale selective logging operations. It excluded 4.5 million hectares of shorter, or more recent, secondary forest that was also associated with the practice of shifting cultivation. (Allen and Bourke 2009; Filer et al. 2009)

The 2014 Global Forest Resources Assessment asserts that the gross forest area still covered 33.6 million hectares. This estimate suggests that there has been no significant reduction in the extent of forest cover since 1975. The area covered by coastal mangroves is said to have gone up from 605,000 hectares in 1975, to 650,000 in 2014. According to the latest official figures, the gross forest area had actually grown to 36 million hectares in 2015, but this was simply because the definition of “forest” had been altered in order to comply with the international standards adopted by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. If the definition had not been changed, the forested area would have shrunk. According to this assessment, the area covered by coastal mangroves had been reduced to 282,000 hectares by 2015. (FAO 2014; GPNG 2019b)

Several other studies suggest a slow but steady decline in the extent of both primary and secondary forests since 1975, at a rate of approximately 0.5 percent per annum. Contraction of the formerly unused forest area is largely due to the failure of forests to regenerate after large-scale selective logging operations or to wholesale forest clearance for large-scale agricultural projects, while contraction of the area covered by secondary forest fallows is partly explained by a shortening of the fallow period in local systems of shifting cultivation. The overall rate of forest clearance is likely to have increased since 2014 because of a steady increase in the number of forest conversion concessions granted for large-scale agricultural projects over the past decade. The latest official assessment reports that 250,000 hectares of formerly forested land was cleared between 2000 and 2015, but the rate of deforestation was increasing towards the end of this period. (Shearman et al. 2008; Filer et al. 2009; Bryan and Shearman 2015; Gabriel et al. 2017; GPNG 2019b)

Over the past three decades, the annual volume of raw log exports has varied from 2.5 to 4 million cubic meters. The fluctuation is mostly explained by changing levels of demand in the Asian markets. Most of the logs are currently exported to China, where they are used to make flooring or furniture. The export of processed wood products has generally accounted for only around 1 percent of the value of raw log exports. The total commercial log harvest could exceed the volume of log exports by 2 or 3 million cubic meters per annum, but no specific figures are available for the domestic consumption of timber for buildings or other durable products. (Bryan and Shearman 2015; Global Witness 2018; Bird et al. 2007a)

Fuelwood consumption is thought to average 1.8 cubic meters per person per annum, which would amount to 15 million cubic meters for the population as a whole — six times higher than the average for Asian countries. The disparity is due to the lack of alternative and affordable energy sources for the rural population. Fuelwood is mostly derived from the clearance of secondary forest fallows by indigenous farmers. (Nuberg 2015)

LEGAL FRAMEWORK

The exploitation of PNG’s forest resources is primarily regulated by the Forestry Act of 1991. This was part of a package of policy reforms that came about due to a judicial inquiry into cases of corruption in the granting of logging concessions. The new legislation was accompanied by various guidelines and regulations applied to the commercial logging industry under the rubric of “sustainable forest management.” (Barnett 1992; Filer and Sekhran 1998; Bird et al. 2007b; Holzknecht and Golman 2009; GPNG 1993, GPNG 1995a, GPNG 1995b)

The Forestry Act prescribes a resource acquisition process by which government officials establish the feasibility of a new logging concession and then acquire the timber harvesting rights from the customary landowners by means of a “forest management agreement” (FMA). It then prescribes a resource allocation process by which the rights are transferred to a logging company by means of a project agreement and the grant of a timber permit. This process should only be applied to areas containing at least 100,000 hectares of “commercially manageable forest” that can sustain an annual harvest of 70,000 cubic meters of timber over a 35–40 year period if the logs are going to be exported, or 30,000 cubic meters if they are processed onshore. The FMA itself should last for 50 years, so that the forest has time to regenerate before a new agreement and a second harvest can be considered. A timber permit should not be granted before the project proponent has obtained a permit from the government agency responsible for environmental management. (GPNG 1993)

The Forestry Act allowed for the continuation of permits granted under the old legislation but envisaged that these would not be renewed unless the concession was subject to a new FMA. This did not please the permit holders, who persuaded the government to relax this condition. In 2011, FMAs covered 5 million hectares of forest land, but another 3.5 million hectares were still covered by concessions operating under older permits that had been extended. Meanwhile, some logging companies had found another way to circumvent the provisions of the new legislation. They obtained another type of permit, known as a timber authority, which should have been restricted to small-scale sawmilling operations harvesting less than 5,000 cubic meters a year, and then accumulated multiple such permits in order to develop a large-scale operation. (Bird et al. 2007c; GPNG 2012)

In 2000, the government established an Independent Forestry Review Team, indirectly funded by the Australian aid program, to investigate abuses of the Forestry Act and recommend remedial action. The government’s failure to implement these recommendations has given rise to a protracted debate about the proportion of PNG’s logging operations and log exports that should be regarded as illegal. The government did amend the Forestry Act in 2000 to close the loophole through which timber authorities had secured large-scale logging operations. However, in 2005 and 2007 the government made further amendments that made it easier for these companies to obtain what are known as forest clearing authorities, permitting their holders to clear forests for large scale agricultural projects. Forty-two of these forest conversion concessions are known to have been granted by the end of 2018, with a combined area of almost 2 million hectares. These concessions were the source of more than 30 percent of PNG’s log exports between 2007 and 2018. The process by which these concessions have been granted is far from transparent. It is also unclear how many of the permit holders will use the revenues from their logging operations to fund the large-scale agricultural projects that they have promised to develop. (Forest Trends 2006; Bird et al. 2007b; CELCOR and ACF 2006; Avosa and Rungol 2011; Scheyvens and Lopez-Casero 2013; Mousseau 2015; Mousseau 2018; Global Witness 2017; Global Witness 2018; Winn 2012; Nelson et al. 2014; Gabriel et al. 2017)

The Forestry Act and associated regulations provide for the protection of some areas of forest within the boundaries of selective logging concessions, but their enforcement has been problematic. Outside of logging concessions, most of the forested areas that are officially protected are, “wildlife management areas” (WMAs) established on customary land and gazetted under the terms of the Fauna (Protection and Control) Act of 1966. While official records make a distinction between terrestrial and marine WMAs, they do not distinguish the terrestrial areas according to the type of ecosystem that is subject to protection because the legislation is mainly concerned with faunal species, not types of vegetation or habitat. Terrestrial WMAs cover less than 700,000 hectares, or 1.5 percent of PNG’s surface area. Three of the largest WMAs cover around 500,000 hectares of land. (GPNG 1995a; GPNG 1995b Bird et al. 2007c; Eaton 1997; Filer 2011; GPNG 2014c; King and Hughes 1998)

There is nothing in the Fauna (Protection and Control) Act which obligates customary owners of a WMA to protect it. Nor does the Fauna Act require the government to play any role in the management of such an area once it has been gazetted. A stronger form of protection is available under the Conservation Areas Act of 1978, but it took more than 30 years (until 2009) for the first conservation area, covering 76,000 hectares, to be gazetted under this legislation. A proposal to gazette a second conservation area, covering 185,000 hectares, has been under consideration for some time. Both areas consist primarily of forest ecosystems but have mainly been justified (and funded) in the name of protecting endangered species of tree kangaroos.

TENURE ISSUES

Section 46 of the Forestry Act says, “[t]he rights of the customary owners of a forest resource shall be fully recognized and respected in all transactions affecting the resource.” While other provisions of the national legal and policy framework indicate a certain level of informed consent to FMAs and distribution of benefits to landowners are required in exchange for the government’s acquisition of timber harvesting rights, the existence of customary rights has not guaranteed the protection of landowner interests in the process of resource acquisition and allocation. Landowners who have been party to these agreements have occasionally sued logging companies for damages, but only one successful suit had been recorded as of 2006. Furthermore, there is no evidence yet that land groups incorporated for the purpose of signing FMAs have been reincorporated to comply with the amendments recently made to the Land Groups Incorporation Act. These groups are therefore at risk of being deregistered, and hence of losing their legal entitlement to landowner benefits before the project development agreements expire. (GPNG 1991; Bird et al. 2007b; Bird et al. 2007c)

The sheer size of the area required for a sustainable log export concession under the terms of the Forestry Act has made it harder to secure the informed consent of all the customary landowners in any given area, since they are typically divided among dozens of different land groups across different villages. This has often resulted in conflict between different factions, represented by local politicians or landowner companies, before and after an FMA has been signed. For this reason, several FMAs have either been revoked or abandoned before a timber permit could be granted to a logging company. (Filer and Wood 2012; Filer 2015)

The risk of conflict between different groups of landowners and the risk that some groups will be deprived of most of their customary rights are even greater in forest conversion concessions that are not covered by FMAs. Some of these forest clearing authorities have been granted on the basis of special agricultural and business leases that last for 99 years and have not yet been revoked or cancelled. In these circumstances, there is evidence that some villagers have lost access to most of the land they used for subsistence purposes. (Mousseau 2013; Gabriel et al. 2017).

GOVERNMENT ADMINISTRATION AND INSTITUTIONS

Responsibility for the grant of all types of logging concession is vested in the PNG Forest Authority (PNGFA) under the terms of the Forestry Act. The PNGFA has its own board, which is meant to include representatives from the logging industry and from civil society and is supposed to provide independent advice to the minister. The board’s managing director is the head of the National Forest Service, whose officials are distributed across the national headquarters and several regional and provincial offices.

The sustainability of the forest management (or selective logging) regime is meant to be guaranteed by a National Forest Plan that is updated every five years and prescribes the scale of the harvest permitted in each province. The national plan is meant to be based on provincial plans approved by Provincial Forest Management Committees (PFMCs). The first national plan was published in 1996, but has only been updated once since, and in a draft version only. This is mainly because forestry officials have been unable to maintain the provincial planning process in all the provinces where new concessions have been proposed. (GPNG 1996c; GPNG 2012; Filer and Sekhran 1998; Bird et al. 2007c)

Under the terms of the Forestry Act, the PFMCs were originally given a substantial role in both the resource acquisition process and the resource allocation process, and they were meant to be the institutional vehicles through which landowner representatives could continue to exercise some influence over the allocation of the timber harvesting rights. However, subsequent amendments to the Forestry Act have shifted some of the powers and responsibilities of these provincial bodies to the National Forest Board. (Holzknecht and Golman 2009)

While provincial forestry officials are responsible for monitoring the compliance of logging companies with national standards of good practice and for ensuring that landowners receive the benefits to which they are entitled, the task of monitoring actual log exports has been contracted out to a private company, SGS PNG Ltd, since 1997. This arrangement has been designed to ensure that the logging companies pay the correct amounts of log export tax to the Internal Revenue Commission. (GPNG 1995a, GPNG 1995b)

National responsibility for the management of protected forest areas beyond the jurisdiction of the PNGFA rests with the Conservation and Environment Protection Authority (CEPA). Nearly all of its staff are based in the national capital and play very limited roles in the actual management of protected areas, except for a few small “national parks” that were established on public land during the colonial period. Some responsibilities for the establishment and management of protected areas have been delegated to provincial and local-level governments, but without the budgetary allocations that would enable them to perform effectively. (GPNG 2014c)

GOVERNMENT REFORMS, INTERVENTIONS AND INVESTMENTS

PNG and Costa Rica were the two founding members of the Coalition for Rainforest Nations in 2005. Since then, the PNG Government has positioned itself as a champion of the campaign for rainforest nations to be compensated by the international community for actions taken to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from deforestation and forest degradation (REDD), including reforestation measures (REDD+). The development of a national policy framework for REDD+ began in the wake of the Copenhagen climate change conference (COP 15) in 2009 and culminated in the publication of a National REDD+ Strategy in 2017. Responsibility for implementation of this strategy is vested in the Climate Change and Development Authority, which, like CEPA, is answerable to the environment minister, and was established under the terms of the Climate Change (Management) Act of 2015. (Babon and Gowae 2013; Babon et al. 2014; GPNG 2017)

There has been some confusion about the relationship of this new agency to the PNGFA, given the size of the forest estate under FMAs and the possibility that some FMAs could be redirected to REDD+ projects instead of logging concessions. Consistent with its REDD+ strategy, the government has promised to reduce the volume of raw log exports, or even put an end to them entirely. These promises have been accompanied by plans to increase the rate of reforestation by providing incentives for logging companies to establish forest plantations in areas of native forest that have been degraded. On the other hand, the latest medium-term development plan aspires to raise the value of forest product exports by almost 150 percent between 2016 and 2022, and revenues from REDD+ projects do not appear to be part of this calculation. (Babon and Gowae 2013; Filer 2015; GPNG 2009a; GPNG 2009b; GPNG 2010a; Bird et al. 2007a; GPNG 2018)

The national government has struggled to devise a set of financial incentives or spending plans that are likely to raise the rate of reforestation or the value of processed forest products by more than a small margin. The area of land under forest plantations is said to have increased from 60,000 hectares in 1990, to 90,000 hectares in 2014, but this is still less than the 110,000 hectares they occupied in 1975. Several studies have shown that the export of raw logs is more profitable than the export of processed timber. Furthermore, timber permits that allow for the export of raw logs cannot be unilaterally changed without the risk of court action by the permit holders, and some of the permits will not expire for years. There is one policy that calls for international standards to be applied to the certification of all local forest products, but this has also met with resistance from the log export industry. Finally, the government’s promises do not seem to apply to the new generation of forest conversion concessions, which are contributing to a growing volume of raw log exports in contradiction to the government’s REDD+ strategy. (FAO 2014; Bird et al. 2007a; GPNG 2014a; Filer 2010)

The articulation of the REDD+ strategy with new policies on the establishment and management of protected areas is also problematic. While the government has long recognized the need to revise and consolidate its legislation on protected areas, its latest policy statement on this subject has not yet been translated into legislation, even though a bill was drafted in 2016. The bill proposes to clarify the distribution of powers and responsibilities between different levels of government. However, there is currently no proposal to raise the level of public spending on the protected areas network, so the financial burden is left to the private sector and the donor community. (GPNG 2014c; GPNG 2016b)

DONOR INTERVENTIONS AND INVESTMENTS