Overview

There is little current and definitive information available on property rights and resource governance in Libya, a country that was ruled by Col. Muammar Qadhafi for 42 years prior to the February 2011 revolution. Though many major donors currently have teams on the ground in the country, it is unclear whether property rights reform is a priority intervention area at the time of this writing, since most of these donors have yet to make information on their current projects publicly available. It must be noted that Libya is in a relatively unique position among developing nations, as the country has resources to finance its own development and is not expected to be reliant on donor funding over the long-term, instead requiring mostly technical assistance.

Property rights were highly insecure under the Qadhafi regime, and the regime’s approach to property governance was defined by its inconsistency. The Libyan government regularly confiscated private land, some of which was redistributed to the landless or to political favorites. A series of successive redistribution efforts culminated in the abolition of private property ownership in 1986, leaving Libyans with only transferable use-rights to land. This led to a rise in social tension and a lack of investor confidence.

Libya is currently in transition. The country’s first elected government was sworn in on November 14, 2012 and one of its primary tasks will be determining the procedures for the drafting of Libya’s new constitution, which will provide the foundation for Libya’s new property rights and resource governance regime. Preliminary steps have already been taken: the post-revolution government has indicated its support of private property rights; the 2011 Constitutional Declaration confirms the inviolability of private property rights in post-Qadhafi Libya; and in March 2013 the Ministry of Justice published a draft law intended to resolve disputes arising from earlier state seizures of property. As Libya seeks to dampen social conflicts and to attract foreign investment, reforms to clarify and strengthen private property rights will become increasingly necessary.

Key Issues and Intervention Constraints

There is substantial donor interest in post-Qadhafi Libya, although at this time publicly available information on intended or ongoing interventions is limited. Libya’s history of insecure and uncertain property rights during Col. Muammar Qadhafi’s 42-year rule has created a need for interventions to clarify, adjust, and strengthen land tenure and property rights. The following interventions are recommended:

Libya’s new government will need to create an entirely new framework for property rights in the country, as the previous government’s approach to law, policy, and enforcement was extremely inconsistent. Donors could support the preparation of new policy in the areas of housing, commercial and industrial property, farm land, forest land, and real property generally that recognize, protect and enable the free exercise of private property rights. Donors could also support the drafting of laws, and assist in the establishment of land administration agencies, to implement these policies.

In the wake of Qadhafi’s ouster, and as a result of government expropriations during the Qadhafi regime, property rights in Libya are extremely unclear. Donors could support conflict-mediation efforts during the transition and the development of legislation and programs to provide an appropriate property restitution scheme. There is some interest in learning how other post-conflict, post-socialist regimes have dealt with the restitution of property to former owners and compensation of current occupants.

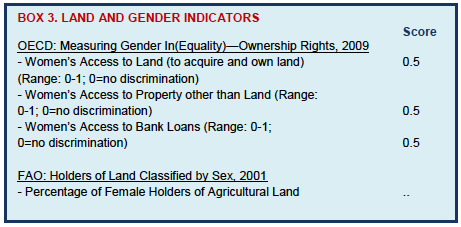

While Qadhafi-era laws protected women’s property rights on paper, reports indicate that in practice women’s rights were dependent upon their relationships with their male family members. In the case of inheritance, while many Libyans purport to follow shari’a-based inheritance rules, which guarantee women some inheritance rights, in some cases these rules are not implemented. It is also unclear whether women’s legal protections will be as strong in Libya’s upcoming constitution. Donors could work with the newly elected government and the Constitutional Committee to ensure that women’s rights are protected under the Libyan constitution and laws, as well as support projects to reinforce women’s rights.

Summary

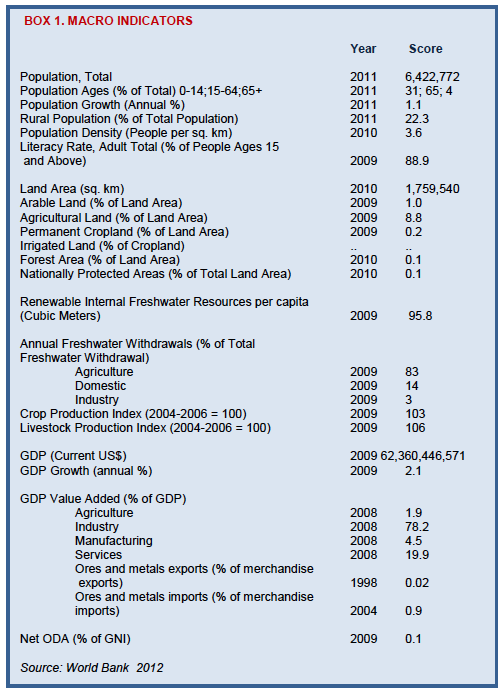

Libya is located on the northern coast of Africa. Though the country is one of the largest on the continent, it has a relatively small population. The country is mainly desert, and the vast majority of the population lives in the coastal regions. Agriculture is limited as a result of climatic conditions, and nearly all agriculture in the country is irrigation-reliant. Most agricultural activity consists of fruits and vegetables grown for domestic consumption. Less than 1% of the country’s land is forested.

There is little definitive information available on land and natural resource management in Libya. During Colonel Muammar Qadhafi’s 42-year rule there was no consistent land and property policy. Forced expropriations by the government were common during the Qadhafi era, and several redistribution programs were attempted during the 1970’s and 1980’s. A series of successive property laws culminated in the legal abolishment of all private property rights in 1986. The post-Qadhafi government has yet to address land and property rights issues, although a draft law to address disputes arising from Qadhafi-era seizures was put forward by the Ministry of Justice in March 2013.

There is little definitive information available on land and natural resource management in Libya. During Colonel Muammar Qadhafi’s 42-year rule there was no consistent land and property policy. Forced expropriations by the government were common during the Qadhafi era, and several redistribution programs were attempted during the 1970’s and 1980’s. A series of successive property laws culminated in the legal abolishment of all private property rights in 1986. The post-Qadhafi government has yet to address land and property rights issues, although a draft law to address disputes arising from Qadhafi-era seizures was put forward by the Ministry of Justice in March 2013.

Though under Qadhafi-era laws women had equal legal rights to property, in practice, women’s economic activity was limited and most women were dependent on their husbands or male relatives for financial support.

The commercial land market in Libya has been severely distorted by the changing law and policies regarding property, as well as the imposition and subsequent lifting of international sanctions. United Nations sanctions imposed on the country in 1992 in response to Libya’s refusal to extradite two men indicted for the 1988 bombing of a Pan Am flight over Lockerbie, Scotland, were lifted in 2003, while many US economic sanctions, in place since the 1980’s, were lifted in 2004. The subsequent opening of Libya’s markets to the world led to a rapid increase in rental prices. Analysts expect significant growth in the property sector in the coming years, provided the current uncertainties can be resolved satisfactorily.

The Qadhafi regime frequently engaged in the compulsory acquisition of private property rights, which it then transferred to landless Libyans, and in many cases to supporters of the regime. Tens of thousands of Libyans whose land was confiscated in the 1970’s and 1980’s are now demanding the return of their property, with some turning to threats and violence to forcibly evict the current occupants, many of whom have lived on the property for decades.

Libya is located mainly in the Sahara Desert and experiences very little rainfall. The country’s main water source is the fossil water extracted from the Nubian Sandstone Aquifer System. Since 1984, the government has been working on construction of the Great Manmade River Project, a series of pipes that transfer fossil water located mainly in the southern regions of the country to the more populated areas to the north. The General Water Authority was established in 1972 and is responsible for management of Libya’s water resources. The Great Manmade River Water Utilization Agency manages water transported through the Great Manmade River Project.

Forestland comprises 0.12% of Libya’s total land area. The country has more planted forest than natural forest as a result of several afforestation programs dating back to 1957.

Libya has the seventh-largest proven oil reserves in the world, and the largest in Africa. Libya has the fourth-largest proven reserves of natural gas in Africa.

Land

LAND USE

Libya is a large country (approx. 1.76 million square kilometers) located on the northern coast of Africa. It is bordered by Egypt and Sudan to the east, Tunisia and Algeria to the west and Chad and Niger to the south, with the Mediterranean Sea acting as the country’s northern border. Libya has a relatively small population of 6.4 million, which is currently growing at a rate of 1.1% annually, down from 2.2% in 2007. Libya’s population is mainly urban, with 22.3% living in rural areas. Less than 3% of Libya’s labor force worked in agriculture in 2011, down from 7.2% in 1996. Women increasingly dominate the agricultural labor force, comprising 73.1% of agricultural workers. The GDP was approximately US $62.4 billion in 2009, with agriculture comprising less than 2%. Libya is one of the least-diversified oil-producing economies in the world; in 2011, oil represented 80% of government revenues and 65% of GDP (FAO 2012a; CIA 2012).

Approximately 1% of Libya’s land is arable, while 95% is desert. Libya is experiencing serious land degradation and desertification as a result of a combination of factors, including the country’s geographic position, global climate change, high rates of urbanization, and overexploitation of water resources and natural vegetation. As a result of the unfavorable conditions, less than 9% of land in Libya is used for agricultural purposes. Nearly 80% of Libya’s agriculture production consists of fruit and vegetables grown for domestic consumption; climatic conditions limit grain production to barley and wheat. Due to the extremely low precipitation rate, most agriculture (over 80%) is heavily reliant on irrigation. Approximately 75% of Libya’s food is imported, and agricultural activity is almost entirely for domestic consumption. Slightly more than one-tenth of one percent of Libya’s land is forested; forestland consists mainly of shrub land in the northern regions (Encyclopedia of Nations n.d.; Saad et al. 2011; USDA 2004; FAO 2006; USDOS 2012).

The vast majority of Libya’s population is urban. It is estimated that 90% of Libya’s 6.4 million people live on just 10% of the land, mainly along the northern Mediterranean coast. In 2003, as much as 86% of Libya’s population lived in urban areas and was concentrated in just four cities -Tripoli, Benghazi, Misrata and Zawya (USDOS 2012).

LAND DISTRIBUTION

In the early decades of the Qadhafi regime, the government regularly confiscated and redistributed land and other properties. Shortly after the 1969 revolution that brought Qadhafi to power, all Italian-owned farms were confiscated and redistributed in smaller plots to Libyans, although some land was retained for state farming enterprises. Uncultivated land was declared state property under Law No. 142 of 1970, while Law No. 37 of 1977 cancelled most property rights, limiting each Libyan family’s property ownership to: (1) the residential property on which they resided; (2) commercial property housing a business which was the owner’s primary source of income, provided he or she personally worked on the property; and (3) an amount of agricultural land to be determined by the Minister of Agriculture. Law No. 4 of 1978, which allowed expropriations for the public good and explicitly limited private ownership to one dwelling for each family, is frequently cited as providing the legal basis for the expropriations of the late 1970’s and 1980’s. All other property was to revert to the state for redistribution to the landless, although it is unclear to what extent land was in fact seized or redistributed. Reports from Libya indicate that some of the confiscated land was transferred to Qadhafi loyalists rather than to landless Libyans (ECA 2010; GoL Law No. 142 1970; GoL Law No. 38 1977; GoL Law No. 4 1978; Worth 2012).

Libya’s total agricultural population, defined as those dependent on agriculture, fishing, hunting or forestry for their livelihoods, is estimated to be 193,000, which includes 50,000 women and 21,000 men considered to be economically active in agriculture. Agriculture in Libya consists mainly of smallholder farms and larger state-owned commercial farming enterprises that are run by state employees. Seventy-three percent of farm landholdings are less than 10 hectares, while large state holdings of over 100 hectares account for less 0.5% of total holdings (FAO 2012a; Laytimi 2006).

LEGAL FRAMEWORK

The Interim National Transitional Council ruled Libya in the immediate aftermath of the revolution until August 2012, having been recognized as the legitimate governing authority of Libya by members of the international community beginning in March 2011. The 2011 Constitutional Declaration, a transitional document put forward by the National Transitional Council, declares property rights inviolable and guarantees property owners the ability to dispose of their property without interference, within the limits of the law. The Constitutional Declaration serves as the basis of rule in Libya until ratification of a full constitution. Libya’s first post-revolution government was sworn in on November 14, 2012. One of its primary tasks will be determining the composition of the constitutional drafting committee (BBC News 2011; GoL Constitutional Declaration of Libya 2011; Max Planck 2012).

Law No. 47 of 2012, which replaced Law No. 36 of 2012, deals with the sequestration and administration of assets and properties belonging to specific individuals associated with Qadhafi. The law names 234 individuals, as well as six businesses, to which it applies. Many of the individuals listed are family members of the former ruler. Those named in the law do not appear to have any right to appeal the freezing of their assets (Libya Herald 2012b).

Law No. 47 of 2012, which replaced Law No. 36 of 2012, deals with the sequestration and administration of assets and properties belonging to specific individuals associated with Qadhafi. The law names 234 individuals, as well as six businesses, to which it applies. Many of the individuals listed are family members of the former ruler. Those named in the law do not appear to have any right to appeal the freezing of their assets (Libya Herald 2012b).

A draft law amending Law No. 4 of 1978 was put forward by the Ministry of Justice in March 2013. The draft addresses compensation and restitution issues arising from the implementation of Law No. 4 and subsequent laws which allowed the state to seize private property, and has been published on the website of the Ministry of Justice for comment (GoL 2013a; GoL 2013b).

Although Article 34 of the Constitutional Declaration repeals all prior constitutional documents and laws, Article 35 of the Declaration confirms the effectiveness of all provisions in existing laws which are not inconsistent with the provisions of the Declaration itself. Many of the property laws described below are incompatible with the Constitutional Declaration’s provision on the inviolability of private property rights and may thus fall under the general repeal of laws outlined in Article 34 (GoL Constitutional Declaration of Libya 2011; UNHCR 2012).

Libya’s Constitutional Declaration of 1969, which repealed the 1951 Constitution, declared public property the basis of development in society, although private property rights were protected to some extent provided they were deemed non-exploitative; no definition of the term “non-exploitative” is provided in the text of the Declaration. Though the Declaration was intended as a transitional document that would eventually be replaced by a permanent constitution, it remained in effect for the entirety of Qadhafi’s 42-year rule (GoL Constitutional Declaration 1969; CEIP n.d.).

Law No. 142 of 1970, on tribal lands, declared all unregistered or unused land to be state property. The law served to limit the influence of customary tribal leaders in the Jabal al Akhdar region who had previously exercised control over communal land claimed by the tribe (GoL Law No. 142 1970; UNHCR 2012; ECA 2010).

Law No. 38 of 1977 cancelled most property rights, limiting each Libyan family to: (1) the residential property on which they resided; (2) the commercial property housing a business which was the owner’s primary source of income, provided he or she personally worked on the property; and (3) an amount of agricultural land to be determined by the Minister of Agriculture. All other property was to revert to the state for redistribution to persons lacking housing, cultivable land or commercial space (GoL Law No. 38 1977; ECA 2010).

Law No. 4 of 1978, also known as the Real Estate Law, declared housing a right of every Libyan, abolished tenancy, and allowed expropriations for the public good. It also explicitly limited private ownership to one dwelling per family, although the law was amended in 2004 to allow ownership of multiple properties. Tenants were transformed into owners, with no compensation paid to the former owners. The property that reverted to the state was intended for redistribution to those in need (GoL Law No. 4 1978; USDOS 2011; UNHCR 2012).

Law No. 7 of 1986 abolished all land ownership, allowing Libyans only use rights to land. The practical effects of this law are unclear, as tenancy had already been abolished under the 1978 law. A reading of the law in the context of the earlier legislation suggests that the change had a mainly legal effect, officially converting landowners into land users, and likely changed little in practice (GoL Law No. 7 1986).

Customary governance systems and practices were restricted by law, if not in reality. Law No. 142 limited the ability of tribal leaders to control what had traditionally been considered tribal land, while the Real Estate Law emphasized use as the basis of land ownership, further limiting the power of customary authorities. Despite these legal limitations, some reports indicate that customary systems for land management continued in much of Libya, though information on customary practices could not be located (UNHCR 2012; ECA 2010).

Customary governance systems and practices were restricted by law, if not in reality. Law No. 142 limited the ability of tribal leaders to control what had traditionally been considered tribal land, while the Real Estate Law emphasized use as the basis of land ownership, further limiting the power of customary authorities. Despite these legal limitations, some reports indicate that customary systems for land management continued in much of Libya, though information on customary practices could not be located (UNHCR 2012; ECA 2010).

TENURE TYPES

Under Qadhafi, all land was, as a general principle, publically owned by law, with Libyans having only transferable use-rights to the land they occupied. Details on the nature of these use-rights were not available at the time of this writing (GoL Law No. 7 1986; Smith and Hartman 2012).

SECURING LAND RIGHTS

As a result of the successive redistribution laws and programs, which culminated in the legal abolishment of private property ownership in 1986, property rights in Libya during the Qadhafi-era were very insecure. Libyan citizens retained transferable use-rights to land. The country operated on a standard civil registration system in which private parties would agree to the terms of transfer and register transfer documentation with local registration offices. These offices maintained paper records of land transactions within their jurisdiction and issued certificates for such rights as existed. No information is available on the extent to which Libyans registered land transactions in fact (GoL Law No. 7 1986; Smith and Hartman 2012).

There is currently a moratorium on land registrations. As of July 2012, Libya’s land registry remained closed, making it difficult to verify registered rights. Even if a registry is reopened, property rights will be difficult to adjudicate, as many records will conflict with prior claims to the property. Qadhafi-era expropriation laws have yet to be repealed, leaving current occupants with valid documentation showing them to be the legal owners of property despite the claims of those from whom the property was confiscated. A new legal framework must be established to adjudicate conflicting claims to property (Libya Business News 2012a; Smith and Hartman 2012).

INTRA-HOUSEHOLD RIGHTS TO LAND AND GENDER DIFFERENCES

Under the law, Libyan women have equal rights to men in almost all areas. The main exception is Libya’s shari’a-based family law, which codifies several practices that can be economically disadvantageous to women, including unequal inheritance rights and the practice of polygamy by men. Under Islamic law, women are generally entitled to an inheritance share half the size of that reserved for their male counterparts. For example, if a father was survived by only his two daughters and one son, and owned one plot of land at the time of his death, the son would be entitled to half the plot while the daughters would each inherit one-fourth of the plot. While this may appear to disadvantage the daughters, it is in fact a larger inheritance than women would likely receive in the absence of the Islamic rule. In reality, Libyan social norms place limits on women’s economic activity, and most Libyan women are financially dependent on their husbands and male relatives. Reports indicate that even shari’a-based protections are not always strictly followed, and women often surrender inheritances of land to male relatives in exchange for cash or other valuable items (Pargeter 2010; Smith and Hartman 2012).

LAND ADMINISTRATION AND INSTITUTIONS

There is no sole ministry within the Libyan government responsible for land management. Agricultural land is overseen by the Ministry of Agriculture, while land containing oil reserves falls under the control the Ministry of Oil. The Ministry of Justice is nominally responsible for the registration of private land rights, while the Ministry of Housing and Utilities is responsible for the Public Property Registry. There are estimated to be 45 to 50 regional land registries in the country, which maintain paper records of many land rights registered during the Qadhafi era (Smith and Hartman 2012).

LAND MARKETS AND INVESTMENTS

Libya’s land market has been based on the transfer of use rights, as private ownership rights were abolished. Transfers of use rights required agreement by the parties, review of relevant documentation by a notary, and submission of documents to the local land registry. The abolishment of private property ownership for investment purposes created a significant price gap between the private land market and the public land market (Ali 2004; Smith and Hartman 2012).

Libya’s commercial land market has been severely distorted as a result of Qadhafi-era practices and policies (or the lack thereof) regarding property, as well as by a lack of basic infrastructure in many areas, and the imposition and later lifting of international sanctions on the country. UN sanctions imposed on Libya in 1992, in response to Qadhafi’s refusal to extradite two men indicted for the 1988 bombing of a Pan Am flight, were lifted in 2003. Many US economic sanctions, in place since the 1980’s, were lifted in 2004. The subsequent opening of Libya’s markets to the world has had an impact on property prices. Foreign individuals and entities have been able to lease property from individual Libyans since 2004, which led to a construction boom as well as to rapidly increasing rental rates for residential properties (Ali 2004; BBC News 2004; USDOS 2011).

Analysts expect to see significant growth in Libya’s property market in the coming years. Libya’s location on the Mediterranean Sea has attracted tourism-related projects, including several by Gulf investors who are currently negotiating a number of proposals. Grade A commercial property space is expected to grow more than nine-fold by 2015. It is believed that growing foreign investment in Libya will provide additional impetus for property-rights reform that clarifies and strengthens rights (Ali 2004; USDOS 2011; Libya Business News 2012a; Smith and Hartman 2012).

COMPULSORY ACQUISITION OF PRIVATE PROPERTY RIGHTS BY GOVERNMENT

Compulsory acquisition and redistribution of land and other property was the hallmark of Qadhafi’s property policy. The Constitutional Declaration of 1969 declared public property the basis of development in society, providing the foundation for several rounds of government expropriations in the following decades (GoL Constitutional Declaration 1969).

One of the Qadhafi regime’s first acts upon coming to power was the confiscation and redistribution of all Italian-owned farms in 1969. In 1970, uncultivated land was declared to be state property. Most other property rights were cancelled in 1977, when Law No. 37 limited land ownership to one residential property and one commercial property per family, as well as an unspecified amount of agricultural land. All other property was to revert to the state for redistribution to the landless, although it is unclear to what extent land was seized or redistributed. Reports indicate that at least some of the land was transferred to Qadhafi loyalists rather than to landless Libyans. Those who received land paid “reduced rate mortgages” to the Libyan government, although exemptions were made based on family income (GoL Law No. 38 1977; Worth 2012; USDOS 2011).

The National Transitional Council’s Constitutional Declaration of 2011 declares private property rights inviolable, suggesting that property rights will be better protected from compulsory acquisition in the post-Qadhafi era. In February 2012, a representative of the Land Ownership Committee announced plans to put forward a law that would return expropriated land and buildings to their former owners. The first phase of the process would return unused property to the original owners, while the second phase would involve relocating families currently occupying expropriated property before ultimately returning that property to the original owners. The Ministry of Justice put forward a draft law addressing compensation and restitution for seized properties in March 2013 (Williams 2012; GoL 2013a; GoL 2013b).

LAND DISPUTES AND CONFLICTS

Restitution and monetary compensation programs meant to remedy the effects of earlier property expropriations by the Libyan government were reportedly underway at the time of the 2011 revolution. Following Qadhafi’s overthrow, tens of thousands of Libyans whose land had been expropriated in the 1970’s and 1980’s began calling for its return. However, many of the current occupants have lived on the property for decades and have paid “mortgages” to the government during that time, while others legitimately purchased the properties from sellers who had gained use rights to the land from the Libyan government (Worth 2012).

Despite the transitional government’s urgings for patience, some former owners have turned to threats and violence to forcibly evict the current occupants of the land they lost in the Qadhafi-era expropriations. Reports indicate that these types of evictions occurred most frequently in the immediate aftermath of the revolution and have lessened significantly in recent months. Plans for a law on restitution were announced in February 2012, and a draft law was made publically available by the Ministry of Justice in March 2013. In addition to the forced evictions described above, several individuals have taken control of land to which they have no rights, disputed or otherwise, and set up businesses. In the absence of effective local government, individual property rights are poorly protected (Worth 2012; UNHCR 2012; Gol 2013a; GoL 2013b; Libya Herald 2012a).

As of June 2012 there remained an estimated 70,000 internally displaced persons (IDPs) in Libya, many of whom are members of communities targeted for mass displacement and dispossession in large part due to suspicions that they are or were Qadhafi loyalists. Virtually all of the residents of the town of Tawergha, which was used as a launching site by Qadhafi forces for their attacks on Misrata during the 2011 revolution, were forced to flee during a two-day assault on the town in August 2011. Although some communities have succeeded in negotiating for their own return, many others, including the former residents of Tawergha, have been unable to return in the face of open hostility from neighboring communities. The National Transitional Council failed to adopt any policy on internal displacement prior to the July 2012 elections (UNHCR 2012; Dagher 2011).

KEY LAND ISSUES AND GOVERNMENT REFORMS, INTERVENTIONS, AND INVESTMENTS

Resolving the conflicts between former owners and current occupiers of confiscated land appears to be a high priority for the newly elected government. A draft law has been made publically available by the Ministry of Justice (Smith and Hartman 2012; GoL 2013a; GoL 2013b).

The Libyan government is in a transitional phase in all areas, including property rights and resource governance. There is recognition of the need for reform in order to create a clear and consistent system which is enforced equally and fairly; however, an overhaul of the country’s property rights laws and systems does not appear to be among the top priorities of the Libyan government at this time. While the reduction of conflict and social tensions provides incentives for property rights reform in the short term, as Libya attracts growing foreign investment it seems likely that the government will reform and strengthen property rights in response to demands for certainty in the property market by foreign investors (Smith and Hartman 2012).

DONOR INTERVENTIONS

USAID’s Libya Transition Initiative (LTI) was launched in June 2011 to support Libyan efforts to build an inclusive and democratic government. The LTI’s work includes support for reconciliation and transitional justice efforts, including in the area of property, as well as constitutional development. The National Democratic Institute has been working with the General National Congress since the 2012 elections to support improved governance through information sessions for GNC members and a series of roundtable discussions between GNC members and their constituents. (USAID 2012; NDI n.d).

DRL’s Transitional Justice Initiative for Libya was launched in October of 2011. The goal of this project, implemented by No Peace Without Justice (NPWJ), is to incorporate transitional justice, accountability and reconciliation within the decision-making processes on post-conflict reconstruction in Libya. The specific objective is to build civil society knowledge in Libya on transitional justice and civil society capacity to work on transitional justice, including as an effective advocate with and resource for policy- and decision-makers on these issues.

DRL is also funding a 12-month Conflict Sensitive Reporting project administered by IREX. This project is supporting journalists in gaining the professional skills needed to contribute to more peaceful democratic development and greater awareness of the threat from conflict rooted in tribal, regional and political rivalry.

DRL is currently launching a JSSR initiative for $1.1M administered by IREX and PILPG which will engage Civil Society, Government and Media for Justice Sector Reform. This project will work to build the capacity of civil society organizations (CSOs) and local leaders to advocate for an inclusive and fair justice reform process, of the government to proactively engage with civil society, and of the media to disseminate advocacy platforms. The project will provide targeted and customized technical assistance to CSOs and media, with a special focus on issues affecting women and minorities.

The Libyan government signed an agreement with the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) in May 2012, with the goal of developing the country’s agricultural sector and improving food security (FAO 2012b).

The International Office of Migration (IOM) has deployed a team in Libya to research land-related issues, as has the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). The University of Leiden is engaged in a research project on land (Smith and Hartman 2012).

Freshwater (Lakes, Rivers, Groundwater)

RESOURCE QUANTITY, QUALITY, USE AND DISTRIBUTION

Water is an extremely scarce resource in Libya, a country that lies almost entirely in the Sahara Desert. The country is heavily dependent on fossil water extracted from the Nubian Sandstone Aquifer System, the world’s largest fossil water aquifer system. In 1984, to combat water scarcity, the government began work on the “Great Manmade River Project” (GMRP). The GMRP is a series of pipelines moving fossil water from the aquifers in the southern parts of the country to the heavily populated coastal regions. Though the project had only completed its first two phases, the GMRP was reportedly supplying up to 70% of Libya’s population with water at the time of the revolution (World Bank 2006; Russeau 2011).

Annual rainfall is extremely low in Libya, where 93% of the land surface receives less than 100 millimeters of rain per year. Rainfall occurs primarily in the winter, although there is variation both annually and between regions. In the coastal region rainfall is generally limited to the winter months, while the Jabal Nafusah and Jabal Akhdar highlands receive enough rainfall to sustain some rain fed agriculture. Rainfall diminishes progressively as one moves southward, eventually reaching zero. Libya’s total renewable groundwater resources are estimated at 500 million cubic meters per year (FAO 2006).

Libya’s total annual water extraction is estimated at 4200 million cubic meters per year, an unsustainable level in a country deemed the fourth most water-stressed country in the arid Middle East and North Africa region. More than 80% of Libya’s total water withdrawal is used for agricultural purposes. Fourteen percent of water withdrawals are directed towards municipal use, with nearly one-third of Libya’s municipal water demand supplied by the GMRP. Industrial use, mainly on the part of the oil industry, accounts for 3% of the country’s total annual water withdrawals (FAO 2006; Maplecroft 2012).

LEGAL FRAMEWORK

The Libyan Water Law, Law No. 3 of 1982, is Libya’s main piece of legislation concerning water management and use. The law declares water a publically owned good which can only be exploited after procurement of a license, defining the amount and duration of use rights, from the Water Authority. The law sets the order of priority for water exploitation as: (1) human and animal use; (2) agricultural use, preferably cultivation of food crops; and (3) industrial and mining uses. The law also details several other aspects of water regulation in Libya, including ownership, management responsibilities, licensing, resource preservation through pollution control, and penalties for violation (Salem 1998).

Several other pieces of legislation complement the Water Law. These include: the Environmental Protection Law; the Water Well Drilling Law; the Economic Crimes Law; the Protection of Ranges and Forests Law; the Agricultural Inspection Law; and the Law of Tribal Lands and Wells (Salem 1998).

Over time there have also been several decrees issued by the Secretary of Agriculture and the General People’s Committee related to water. These include: a 1979 decision by the Secretary of Agriculture banning the drilling of water wells in the Gefara Plain; a 1981 declaration by the General People’s Committee adopting measures for the planning and development of Libya’s coastal belt; and a 1983 decision by the Secretary of Agriculture regulating irrigation (Salem 1998; FAO 2006).

TENURE ISSUES

No information is available.

GOVERNMENT ADMINISTRATION AND INSTITUTIONS

The General Water Authority, established in 1972, is responsible for all water resources assessment and monitoring in Libya. Among its many responsibilities, the Authority supervises irrigation and drainage projects, performs studies aimed at improving the irrigation network, and has a central laboratory for the analysis of water and soils. It is composed of the following six general directorates: Planning; Follow-up and Statistics; Water Resources; Dams; Irrigation and Drainage; Soils; and Finance and Administration (FAO 2006).

Responsibility for the development of irrigation for agriculture, as well as the implementation of major water-related projects, rests with the Secretariat of Agriculture and Animal Wealth (FAO 2006).

The Great Manmade River Water Utilization Authority is a special authority established for the management of water transported by the GMRP. The Authority is publicly owned and financed through various taxes, including a special tax imposed on water sales and most imports, as well as taxes collected on some petroleum products and tobacco (World Bank 2006).

GOVERNMENT REFORMS, INTERVENTIONS, AND INVESTMENTS

Decree No. 196 of 1996 created a national water committee comprised of fourteen members representing various water sectors. The committee was tasked with preparing a comprehensive report on Libya’s water resources and developing a long-term water strategy for the country; it is unclear if the report was in fact produced (Salem 1998).

DONOR INTERVENTIONS AND INVESTMENTS

No information is available.

Trees and Forests

RESOURCE QUANTITY, QUALITY, USE AND DISTRIBUTION

Forestland comprises 0.12% of Libya’s total land area, covering approximately 400,000 hectares. Forested land is located along the Northeastern coast, and consists mainly of shrub land and mosaic vegetation. Vegetation is sparse, particularly in the desert areas, although oases support the growth of date palms as well as olive and orange trees (FAO 2012a; FAO 2012c).

As a result of afforestation efforts by the Libyan government dating back to 1957, Libya has more planted forest than natural forest. Several forested areas and nature reserves are classified as nationally protected areas by the Libyan government (FAO 2004).

LEGAL FRAMEWORK

The 2011 Constitutional Declaration does not address forests or environmental management, nor do any laws addressing these issues appear to have been promulgated by the post-Qadhafi governments (GoL Constitutional Declaration of Libya 2011).

Several laws were passed during the Qadhafi era for the protection of forests and the environment in general, including: Law No. 46 of 1972, for the protection of shrub land; Law No. 5 of 1982, for the protection of pastures and forests; Law No. 7 of 1982, for the protection of the environment; Law No. 15 of 1984, for the protection of animals and trees; and Law No. 15 of 1992, for the protection of agricultural lands, pastures and forests (Saad et al. 2011).

TENURE ISSUES

No information is available.

GOVERNMENT ADMINISTRATION AND INSTITUTIONS

No information is available.

GOVERNMENT REFORMS, INTERVENTIONS, AND INVESTMENTS

Prior to 1957, Libya’s only wooded area was the Akhdar Mountains area where there were some regions of scrub brush. Government afforestation programs began in 1957 and were accelerated in the 1970’s. By 1977, 213 million seedlings had been planted, mainly in western Libya. The long-term goals of the afforestation programs included combating desertification and the growing of enough trees to meet the country’s domestic lumber needs, while short-term goals included soil conservation and the creation of windbreaks for crops (FAO 2004; Saad et al. 2011).

Several additional measures have also been taken by the Libyan government to combat desertification, including: curbing sand dunes; the establishment of terraces to combat soil erosion; protection of natural pastures; and the preservation of rainwater on sloping agricultural land (Saad et al. 2011).

DONOR INTERVENTIONS AND INVESTMENTS

No information is available.

Minerals

RESOURCE QUANTITY, QUALITY, USE AND DISTRIBUTION

With 47.1 billion barrels of oil, Libya has the largest proven reserves in Africa and the seventh-largest proven reserves in the world. The vast majority (80%) of the oil reserves are located in the Sirte basin in northeast Libya (USEIA 2012).

Libya is one of the least-diversified oil-producing economies in the world: oil was responsible for 80% of government revenues and 65% of GDP in 2011. In 2010 the country’s average production level was approximately 1.7 million barrels per day, making Libya the fourth-largest producer of oil in Africa. More than 70% of Libya’s oil is exported to Europe (CIA 2012).

Libya has the fourth-largest proven reserves of natural gas in Africa, after Nigeria, Algeria and Egypt. The country produced 30.6 billion cubic meters of natural gas in 2010 (Taib 2012).

Libya also produces cement, iron, gypsum, lime, methanol, salt, steel and sulfur. In 2010, the Libyan government identified sites of minable minerals throughout the country and identified clays, coal, dimension stone, diatomite, dolomite, gold, gypsum, iron ore, limestone, salt, silica sand and travertine as commodities with economic mining potential. The stated goal of this exercise was diversification of the Libyan economy (Taib 2012).

LEGAL FRAMEWORK

The 2011 Constitutional Declaration does not address minerals or oil. Ownership and management of mineral resources remains unaddressed by the laws put forth by both the National Transitional Council and the General National Congress (GoL Constitutional Declaration of Libya 2011).

Under Qadhafi, Libya’s oil and natural gas sector was governed by Petroleum Law No. 25 of 1955, as well as Petroleum Regulations No. 8 and No. 9. The oil and natural gas sector was also affected by Law No. 443 of 2006, which required all foreign companies to operate as joint ventures with local partners holding a minimum of a 35% share (Taib 2012).

Law No. 2 of 1971 regulated mining and quarrying activities. In 1996 the General People’s Committee issued Decree No. 151, creating the Libyan Mining Company. The Company’s directive included attracting foreign investment in the mining sector and ensuring that domestic production met national demand (Taib 2012).

TENURE ISSUES

Libya has historically been divided into three regions: Tripolitania in the west, Cyrenaica in the east, and Fezzan, the sparsely populated southern region. Prior to Qadhafi’s rule, the regions were administered separately under a federalist system. Post-Qadhafi, Libya has seen the resurgence of a separatist movement in the east calling for a return to a federalist system of governance. These calls have been met with opposition from the national government, in part because 75% percent of Libya’s oil reserves are located in the eastern region, while two-thirds of the country’s population lives in the west (Russia Today 2012; UPI 2012).

GOVERNMENT ADMINISTRATION AND INSTITUTIONS

Under Qadhafi, Libya’s oil sector was run by the state-owned National Oil Corporation (NOC), which was responsible for implementing exploration and production-sharing agreements with international oil companies, as well as its own field activities. In 1974, the Libyan government introduced the Exploration and Production Sharing Agreement (EPSA), which governs the relationship between NOC and international oil companies. There have been several versions of EPSA released, with the most recent, EPSA IV, introduced in January 2005. EPSA IV’s terms have been deemed unfavorable by international oil companies, in part due to a bidding process which awards contracts based mainly on the share of production and signing bonuses offered to NOC. As a result, under EPSA IV, NOC regularly takes 80–90% of oil and gas production, while the oil companies bear the brunt of the costs associated with exploration and development. EPSA V is under development, and its terms are expected to be more favorable to international oil companies (USEIA 2012; Booth and Kordvani 2012; Libya Business News 2012d).

The National Transitional Council reestablished the Ministry of Oil, which Qadhafi had abolished in 2006. The Ministry will be responsible for development of the national oil policy, while the National Oil Corporation remains responsible for management of the commercial end of the oil industry. This measure is expected to improve consistency and transparency in the oil industry (African Economic Outlook 2012).

GOVERNMENT REFORMS, INTERVENTIONS, AND INVESTMENTS

Libya’s oil production was disrupted in February 2011 by the revolution, and production remained minimal and sporadic during the months of fighting. Production resumed in September 2011, and the oil sector recovered at an unexpectedly fast pace. By May 2012, production had reached 1.4 million barrels per day, nearing the country’s pre-revolution production of 1.65 million barrels per day. The new government aims to reach production levels of 3 million barrels per day by the end of 2015. However, efforts to achieve this goal are undermined by the continued security threat posed by local militias, which has made foreign oil workers hesitant to return (USEIA 2012; UPI 2012).

Though the Ministry of Oil and the National Oil Corporation have agreed to respect existing oil contracts, they have also announced that those suspected of corrupt activities in the past will be subject to investigations. A twenty-member panel convened by the National Transitional Council is in the process of reviewing more than 10,000 business contracts signed by the former regime, including oil contracts, searching for evidence of corruption as well as ensuring the fairness of the agreements (African Economic Outlook 2012; Libya Business News 2012b).

In June 2012, the Minister of Oil and Gas announced plans to offer new production-sharing agreements to international oil companies, although a timeline was not established. In December 2012, the Minister stated that Libya may be ready to open bidding for the next round of oil agreements by August 2013. He has also said the next round of agreements, EPSA V, will include more favorable terms for foreign oil companies than EPSA IV (Libya Business News 2012c; Libya Business News 2012d).

DONOR INTERVENTIONS AND INVESTMENTS

No information is available.