The Challenge

Rural Kwale County lies in Kenya’s southern corner along the Tanzanian border and just below the coastal city of Mombasa. Coastal regions, including Kwale, have different ethnic, religious and cultural heritages from inland areas in Kenya.1 The county has a poverty rate of 75 percent and has historically received relatively little attention from the national government in services and infrastructure.2 Land governance is one aspect where this lack of attention is apparent. Today, less than a quarter of the land in Kwale County has a documented title deed, and only 10 percent of title-holders are women.3

Rural Kwale County lies in Kenya’s southern corner along the Tanzanian border and just below the coastal city of Mombasa. Coastal regions, including Kwale, have different ethnic, religious and cultural heritages from inland areas in Kenya.1 The county has a poverty rate of 75 percent and has historically received relatively little attention from the national government in services and infrastructure.2 Land governance is one aspect where this lack of attention is apparent. Today, less than a quarter of the land in Kwale County has a documented title deed, and only 10 percent of title-holders are women.3

Colonial-era land policies allowed white settlers and local elites to acquire large parcels of land in coastal regions. This displaced indigenous peoples who did not have the same access to the land titling process and created grievances. Much of the land is now held by absentee landlords whose rights to land are often contested. Land with government documentation is more likely to be found in areas adjacent to and within towns, cities and settlements, rather than in rural areas. This adds to tensions between long-settled groups and people who have more recently moved into the area.

To address the land titling issue, the county government has set a target to provide titles to 30 percent of local residents, and an additional 30 percent to outsiders who come to acquire land near the county’s beautiful beaches or for investment. However, it is easier for outsiders to navigate the tilting process due to greater resource access and requirements that are sometimes relaxed. As a result, small-scale farmers and landless individuals often find themselves without documented land rights, which fosters, among other things, insecurity, unsustainable land use practices, and an inability to access credit due to a lack of collateral.

The tensions and historic grievances related to land mean Kwale County is also a site of conflict and violence. This conflict can be exacerbated by private investments if the land rights of local people are not recognized and respected. Family farms face risks of displacement and loss of livelihoods from infrastructure development and large-scale extractive operations. The development of mines is a specific threat to both land and water rights in Kwale County. Prospective investments, whether for mining, agribusiness or tourism, threaten to take more land from local people whose rights are insecure.

When the land rights of rural community members are recognized and respected, it can reduce conflict, promote food security and encourage more diverse livelihoods. This can make communities more prosperous and self-reliant. Under the right conditions, agroforestry—with diverse crop and tree regimes—can provide one such opportunity to transform rural livelihoods. However, trees take years to mature, and insecure land rights may make agroforestry plots vulnerable to seizure by more powerful actors. For farmers to invest in planting and growing trees, they need to believe their land rights are secure. They also need a stable policy environment to ensure their rights to land and trees will be respected over time. Agroforestry firms need the same stable policy environment and secure land rights to be comfortable investing and to be profitable.

1 “Unfinished business: Kenya’s efforts to address displacement and and land issues in Coast Region,” July, 2014, NRC/IDMC/KNCHR, http://www.internal-displacement.org/assets/publications/2014/201407-af-kenya-unfinished-business-en.pdf

2 Kenya County Fact Sheets, World Bank, 2011, http://siteresources.worldbank.org/INTAFRICA/Resources/257994-1335471959878/Kenya_County_Fact_Sheets_Dec2011.pdf.

3 http://www.kwalecountygov.com/index.php?option=com_content&view=featured&Itemid=935https://agriknowledge.org/downloads/08612n57q.

The Innovation

The Moringa Partnership (hereafter Moringa) is a private impact investment firm focused on supporting sustainable agroforestry. The Partnership manages the nearly $100 million Moringa Fund, developed to identify and invest in projects that have the potential to deliver financial returns as well as social and environmental benefits for the local communities at investment sites. Moringa has provided capital and technical assistance to ensure that its investments are profitable and that risks are mitigated over the short and long term.

The Moringa Partnership (hereafter Moringa) is a private impact investment firm focused on supporting sustainable agroforestry. The Partnership manages the nearly $100 million Moringa Fund, developed to identify and invest in projects that have the potential to deliver financial returns as well as social and environmental benefits for the local communities at investment sites. Moringa has provided capital and technical assistance to ensure that its investments are profitable and that risks are mitigated over the short and long term.

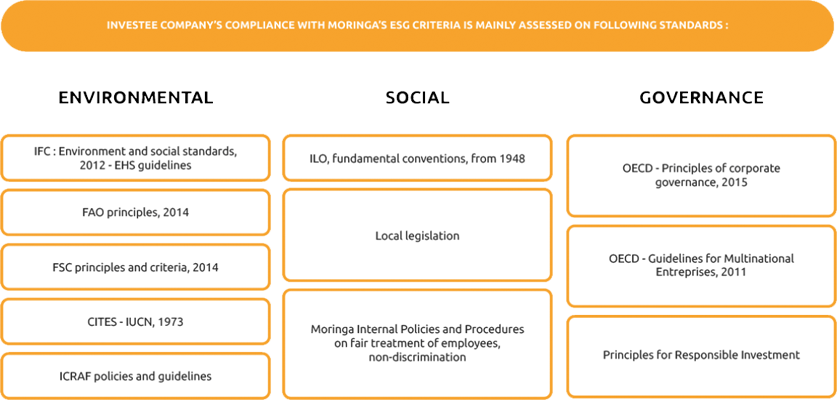

Moringa uses strict Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) policies and standards (see the chart below) to select its investees, although these firms vary in their levels of compliance with these standards. Moringa works with investees to strengthen their weaker areas of ESG compliance.

In 2017, Moringa made a minority investment in the Kenya firm Asante Capital (hereafter Asante), a timber and veneer processing company that is also testing the production of moringa powder and ginger oil to determine whether these are viable markets. As a minority shareholder with a significant degree of influence, Moringa is entitled to understand if this investment is aligned with ESG standards and to determine the potential social impact of Asante’s activities and operations.

In particular, Moringa sought to learn:

In particular, Moringa sought to learn:

- How Asante acquired its land;

- What consultations took place with local land holders;

- What the implications of timber, moringa and ginger production on local food and water security were; and

- How Asante planned to address conflicts related to land use or acquisition.

Moringa partnered with USAID to seek the answers to these questions via the adoption and field testing of the Analytical Framework for the Asante investment. Asante has a small-scale processing facility and several timber holdings in Kwale County, including tree plantations, land planted with ginger and an export-processing zone for wood veneer and other goods. The company is hoping to acquire more land to expand its timber holdings and grow its business.

Together with a group of local researchers and experts from Kenya and other countries, USAID Implementing Partner, Indufor North America, was able to dive into the history of the land holdings for both Asante and the growers. Indufor then crafted a nuanced picture of the relationship between land and environmental concerns that might be important for Moringa’s investment into Asante.

“We structured an approach where we very closely aligned ourselves with the Analytical Framework and its five sections. The investment we were looking at had multiple land holdings and a geographic area that was quite extensive. Land was held by growers and contracted to the processor, land was held by the company we were assessing, and land was under consideration for acquisition, so there was a lot of diversity in types of land holdings, the legal structures underpinning them and then the actual users of the land. So unpacking the Analytical Framework for application and testing allowed us to figure out which questions were more important, which were easy to answer quickly, which needed documentation or which required in-the-field interviews with local stakeholders.”

Jeffrey Hatcher, Managing Director, Indufor, North America

With this broader understanding of the on-the-ground realities, Moringa will be better placed to work with Asante to improve its operations and land acquisition policies and practices. This will also enable Moringa to provide targeted technical assistance to the farmers and growers that contribute to Asante’s supply chain and should lead to a more sustainable investment that meets Moringa’s goal: to achieve a triple bottom line.

“We are an impact investment firm. We want to support family farmers by giving them technologies, plans to get technical advice, different kinds of support. Because we are working on agroforestry— tree plantations with crops— there are many issues around tree planting. Sometimes the farmers do not have proper titles. Sometimes they rent to others and there are questions around what they can and cannot plant on this land. We want to give them the right support but need to understand how land tenure impacts the potential for production.”

Clement Chenost,

Director, The Moringa Partnership

Part of Asante’s supply chain consists of farmers who grow moringa trees and ginger on their own parcels of land. Ginger oil and moringa powder production are secondary activities for Asante, who is testing their viability in Kwale County. Asante is working with 22 growers to supply seedlings, extension services and, in some cases, credit for irrigation equipment to local farmers. These farmers, who hold small plots, need consistent and secure land rights to make investments that would allow them to cultivate moringa and ginger and generate a return on these infrastructure improvements. This is particularly important in the case of ginger, a water-dependent crop, that must use irrigation technologies that can be costly to install. Farmers are only likely to make these investments when their land claims are secure.

Project activities focused on:

- Conducting a thorough land tenure risk assessment of Asante’s land holdings and the land tenure environment in areas where Asante growers are located;

- Consulting communities to develop strategies to manage any identified land tenure risks;

- Mapping the location of growers’ farms to better understand where timber supply to Asante originates; and

- Incorporating an environmental impact assessment of the investment with particular emphasis on water use, access and sustainability.

These activities were designed to help Moringa and Asante identify and mitigate any existing or prospective land-related risks. These risks can take the form of legacy land challenges, intergenerational land transfers and related exposure to risks associated with water access and availability.

The Champions

Esther Mutuma

As CEO, Esther Mutuma has been the public face of Asante and has an important role to maintain relationships between community members, particularly Asante’s local employees, and the organization. This role has made her well-versed in the challenges that growers and other producers face in the areas where Asante works. One of her goals is to identify how different stakeholders might work together in a collaborative way to address mutual concerns such as water resource risks.

Over the next two years, Esther expects Asante to operationalize new processes and procedures around water access and availability. This will allow Asante to incorporate their new knowledge of location-specific water usage and demands. It will also help the company to utilize best practices for site selection and ensure sustainable operations and community water supplies alike. The project has helped to clarify the need for diverse water resource interventions based on Asante’s crops and community needs. Esther and Asante colleagues hope that farmers will be empowered to make decisions and take the lead to propose new solutions. Eventually, Asante would like to establish a permanent source to fund water infrastructure and interventions as part of its corporate social responsibility initiatives. Local knowledge and community buy-in around investor solutions for water and natural resource management can help Investors to increase efficiency and improve the site selection process. It can also help investors to mitigate risks to their operations and ensure equitable natural resource access and use for communities.

Jackson Museye

As local cooperative SCOFOA’s organizing secretary, Jackson educates community members on the benefits of tree planting. He cultivates a number of tree species on his own property. He demonstrates good environmental management through conservation of the natural forest on his land. Jackson also patrols the community to prevent deforestation by other members and replants trees when degradation occurs.

Jackson is the holder of a large parcel of titled land where he has employed technologies, such as solar irrigation. Even though Jackson has a title, he still faces tenure challenges. He is concerned about people coming onto his land to cut down his trees. And while he formally owns his land, others have contested his claim and elevated their case to a Kenyan high court.

Despite this, Jackson has used these challenges as an opportunity to educate others on the purpose and benefits of being part of the cooperative and a supplier to Asante. He has encouraged his neighbors to join the group and has de-escalated some of the tensions in his community regarding land rights as a result.

Investor support for community-owned organizations and cooperatives like SCOFOA can help to mitigate the risk of conflict and encourage proactive, peer-to-peer conflict resolution. Additional benefits of the SCOFOA-Asante partnership that Jackson has communicated to members include improved market access, a sense of hope around future outcomes, enhanced community inclusion and motivation to plant and conserve trees.

The Impact

By clarifying on-the-ground realities, the Responsible Investment Project in Kenya demonstrates the value of enhanced due diligence related to land and environmental risks. A thorough due diligence process provided Moringa with critical information about land and environmental issues that have the potential to impact the supply of timber, ginger and moringa to its investee, Asante Capital. At the same time, this assessment enabled Moringa and Asante to identify where their growers are located and what information and assistance they need to be more productive and self-reliant. It also provided Moringa and Asante with the opportunity to engage in a more targeted manner with stakeholders and suppliers. The project showed that the process for investing responsibly is not easy. It takes the commitment of staff and resources to gather and analyze this sometimes “hard to reach” data.

By clarifying on-the-ground realities, the Responsible Investment Project in Kenya demonstrates the value of enhanced due diligence related to land and environmental risks. A thorough due diligence process provided Moringa with critical information about land and environmental issues that have the potential to impact the supply of timber, ginger and moringa to its investee, Asante Capital. At the same time, this assessment enabled Moringa and Asante to identify where their growers are located and what information and assistance they need to be more productive and self-reliant. It also provided Moringa and Asante with the opportunity to engage in a more targeted manner with stakeholders and suppliers. The project showed that the process for investing responsibly is not easy. It takes the commitment of staff and resources to gather and analyze this sometimes “hard to reach” data.

As a result of the project, Moringa was able to:

- Identify the potential for land risks in Kwale County that might impact Asante Capital and its growers;

- Understand resource concerns and constraints that might impact production over time, particularly access to dependable water supplies for ginger production;

- Clarify legal provisions and regulatory requirements with regard to land acquisition and use in Kwale County;

- Work with Asante Capital to strengthen due diligence processes for future land acquisitions, including developing stakeholder engagement procedures; and

- Define the kinds of technical assistance that growers may need to improve productivity.

For Asante, the project highlighted gaps that need to be addressed, including:

- Improved community engagement and consultation with local land holders during any land acquisition process;

- Development of a formal grievance mechanism to address conflicts with growers and other local stakeholders including neighboring land holders;

- Clarity on county-level permits the company requires, which include permission to grow ginger and to convert agricultural land into processing facilities;

- Clarity on national-level permits the company requires; and

- Greater understanding of where growers are located and prospective sites for future expansion.

In addition, the project generated lessons learned for Asante related to water resource management and the importance of a thorough analysis of water resource availability prior to engaging in land use activities. The project has encouraged Asante to better understand the productive requirements of its fields and plantations to improve future site selection processes. Asante will also consider how to capture water during the wettest times of the year to safeguard their investments in the dry season.

In addition, the project generated lessons learned for Asante related to water resource management and the importance of a thorough analysis of water resource availability prior to engaging in land use activities. The project has encouraged Asante to better understand the productive requirements of its fields and plantations to improve future site selection processes. Asante will also consider how to capture water during the wettest times of the year to safeguard their investments in the dry season.

Local growers and members of SCOFOA seem optimistic about future opportunities to work with Asante Capital. These stakeholders hope to:

- Diversify production towards higher-value timber, moringa and ginger;

- Gain access to extension services and technical assistance to improve water resource management and irrigation technology;

- Increase community-level cooperation around shared water resources; and

- Foster a culture of tree-planting moving forward to help increase resilience to a variety of natural shocks, as planting local tree species in particular can be an important tool in combating inefficient water use.

The Responsible Investment Project in Kenya demonstrates the benefit of an enhanced due diligence process to mitigate land-based risks for companies. Further, by working closely with growers in rural communities, the project was able to improve land and water management and recognize the land rights of family farmers. Taking steps early in an investment process can help avoid or mitigate problems that could contribute to conflict, negatively impact supply chains and operations, and limit the potential for longer-term growth for firms and communities.

Investors can reduce the significant risks associated with unclear ownership to land in developing economies. Guidelines and implementing tools can be the essential building blocks to help the private sector to create sustainable investment projects from the ground up. Partnering with local farmers to strengthen land rights, even in the absence of national government partnership, can be a practical step toward creating long-term and mutually beneficial investments.

Through project activities, USAID and partners are using innovative solutions to make private sector investment more responsible by respecting local land rights and building communities’ self-reliance.