How a land surveyor in Meta’s Regional Land Office has overcome challenges to find herself in a career dominated by men.

Leany Alba, 28, grew up in Bogota and dreamed of being a professional photographer, but her parents never warmed up to the idea. She always loves maps and followed a career path towards becoming a cartographer. On that path, she found a burgeoning job market for her current profession: land surveyor.

Leany Alba, 28, grew up in Bogota and dreamed of being a professional photographer, but her parents never warmed up to the idea. She always loves maps and followed a career path towards becoming a cartographer. On that path, she found a burgeoning job market for her current profession: land surveyor.

For years, geographers, cartographers, and topographers were considered occupations for “strong, young men.” Alba bucked the trend when she took her first job with Colombia’s Land Restitution Unit as a topographer, surveying properties that were being returned to displaced families in Meta. Though her parents had once worried about their daughter, imagining her measuring buildings on urban construction sites, they supported her decision to work in rural Colombia.

“These jobs were once dominated by men, because it was much more physical. But this is nonsense. A woman can endure the high temperatures and carry equipment just like a man,” says Leany.

Leany Alba works in some of Meta´s most isolated municipalities, in partnership with the regional and municipal governments, surveying urban properties to make land rights a reality for thousands of Colombians.

In 2022, she accepted a job with the Meta Regional Land Office, as the only woman topographer on a team of land formalization experts who regularly travel to rural municipalities to assist small-town mayors with the titling of urban parcels.

“With today’s technology, there is no excuse. Any woman can work as a land surveyor.” says Leanny.

“With today’s technology, there is no excuse. Any woman can work as a land surveyor.” says Leanny.

Meta’s Regional Land Office supports municipalities like Mesetas, La Uribe and La Macarena, focusing on titling properties in the towns’ urban areas. Underfunded municipalities like Mesetas cannot afford to maintain its own land office, so the regional strategy allows it to share the costs of land titling, like labor and equipment, with a group of municipalities.

The innovative concept was first supported by USAID in the Department of Meta, and has found success in other departments like Cauca, Sucre, and Bolívar. The regional land office strategy has planted seeds for regional-level leadership in land administration and created a conduit of support for secure land rights.

“So one of the challenges is communication with people. Women often have better communications skills, and it is necessary to have a certain tact in dealing with rural people, since almost nobody understands land” explains Leany Alba.

“So one of the challenges is communication with people. Women often have better communications skills, and it is necessary to have a certain tact in dealing with rural people, since almost nobody understands land” explains Leany Alba.

In a little over a year, Meta’s Regional Land Office has delivered nearly 700 urban land titles, which include 34 public properties with schools, health clinics, and municipal services like parks and recreation. The Regional Land Office has titled properties in Mesetas, La Macarena, Uribe, Vista Hermosa, San Juan de Arama, and Puerto Rico.

“We as coffee growers work for the common good. More than coffee, it is us, a part of the countryside who are taking care of the environment,”

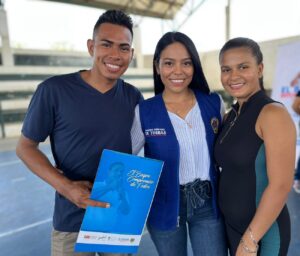

“We as coffee growers work for the common good. More than coffee, it is us, a part of the countryside who are taking care of the environment,”  Fanllany Mendez and the 10 associations participated in coffee cupping, exposition of production machinery, and business meetings with buyers from Taiwan, South Korea, Mexico, Peru, China and Colombia. The coffee growers, who a decade ago had no market channels available, came to the fair to prove that in the municipalities of Northern Cauca are also producing specialty coffee with added value.

Fanllany Mendez and the 10 associations participated in coffee cupping, exposition of production machinery, and business meetings with buyers from Taiwan, South Korea, Mexico, Peru, China and Colombia. The coffee growers, who a decade ago had no market channels available, came to the fair to prove that in the municipalities of Northern Cauca are also producing specialty coffee with added value.

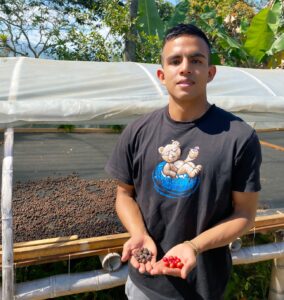

Santiago Samboní is a 21-year-old who has always grown coffee with his mother and grandmother on their farm located in the rural area of Santander de Quilichao. For Santiago, being a successful coffee grower is more than just production, it’s about training and acquiring knowledge that can improve the process. Today he is studying to become a food engineer.

Santiago Samboní is a 21-year-old who has always grown coffee with his mother and grandmother on their farm located in the rural area of Santander de Quilichao. For Santiago, being a successful coffee grower is more than just production, it’s about training and acquiring knowledge that can improve the process. Today he is studying to become a food engineer.

Tell us about yourself.

Tell us about yourself.

Eleven ethnic Pijao communities in the municipality of Chaparral, Tolima, took part in Free, Prior, and Informed Consent (FPIC) sessions and agreed to participate in the implementation of Rural Property and Land Administration Plan (POSPR) being carried out by USAID Land for Prosperity with support from the Colombian government.

Eleven ethnic Pijao communities in the municipality of Chaparral, Tolima, took part in Free, Prior, and Informed Consent (FPIC) sessions and agreed to participate in the implementation of Rural Property and Land Administration Plan (POSPR) being carried out by USAID Land for Prosperity with support from the Colombian government. “This is a great opportunity for indigenous communities to advance the process of establishing collective landholdings, strengthen our family bonds, and ensure the persistence of the Pijao culture,” says Maria Ximena Figueroa, Pijao social leader from the Matora de Maito Pijao community.

“This is a great opportunity for indigenous communities to advance the process of establishing collective landholdings, strengthen our family bonds, and ensure the persistence of the Pijao culture,” says Maria Ximena Figueroa, Pijao social leader from the Matora de Maito Pijao community. “There is confusion in the community around land formalization, ranging from ideas that the government is coming to take our land to ideas that the government is finally making reparations,” says Luis Fernando Guerrero, the current governor of Matora de Maito.

“There is confusion in the community around land formalization, ranging from ideas that the government is coming to take our land to ideas that the government is finally making reparations,” says Luis Fernando Guerrero, the current governor of Matora de Maito. In 2010, Matora de Maito purchased a three-hectare parcel to build their maloca, or community meeting center, near the urban center of Chaparral. “The problem is that we still don’t own a larger piece of collective land where we can work together and use the land the way we always have,” explains the group’s governor, Luis Fernando Guerrero.

In 2010, Matora de Maito purchased a three-hectare parcel to build their maloca, or community meeting center, near the urban center of Chaparral. “The problem is that we still don’t own a larger piece of collective land where we can work together and use the land the way we always have,” explains the group’s governor, Luis Fernando Guerrero. “We all want a collective territory where we can record our own history and leave a legacy for our children. Our communities need assistance with the application for a resguardo.” says José Walter Cano, Governor of the Pijaos en Evolución, a group of 26 Pijao families.

“We all want a collective territory where we can record our own history and leave a legacy for our children. Our communities need assistance with the application for a resguardo.” says José Walter Cano, Governor of the Pijaos en Evolución, a group of 26 Pijao families.

El Bagre is synonymous with gold mining. In fact, before El Bagre was a municipality, it formed part of neighboring Zaragoza and was a place where people had been mining gold for hundreds of years. For the last several decades, Colombian mining firm Mineros has carried out alluvial mining across large swathes of the gold-rich land. According to experts, El Bagre is one of Antioquia’s highest gold producing municipalities and depends on gold for 80-90% of its revenue.

El Bagre is synonymous with gold mining. In fact, before El Bagre was a municipality, it formed part of neighboring Zaragoza and was a place where people had been mining gold for hundreds of years. For the last several decades, Colombian mining firm Mineros has carried out alluvial mining across large swathes of the gold-rich land. According to experts, El Bagre is one of Antioquia’s highest gold producing municipalities and depends on gold for 80-90% of its revenue. In May, El Bagre’s Land Office delivered 90 property titles to residents, bringing the total number of land titles delivered to more than 500 since the office was created.

In May, El Bagre’s Land Office delivered 90 property titles to residents, bringing the total number of land titles delivered to more than 500 since the office was created. “Nobody believed the Municipal Land Office would help them with land titling services for free. But once we delivered more than 150 land titles at our first event in 2021, people gained confidence in what the administration is trying to do,” Gomez says.

“Nobody believed the Municipal Land Office would help them with land titling services for free. But once we delivered more than 150 land titles at our first event in 2021, people gained confidence in what the administration is trying to do,” Gomez says. El Bagre’s Municipal Land Office is also facilitating housing subsidies for new homeowners with a registered land title who qualify for the program. In 2023, the MLO helped 66 homeowners access government subsidies offered by Antioquia’s departmental government, permitting low-income residents to improve their flooring, bathrooms, and kitchen.

El Bagre’s Municipal Land Office is also facilitating housing subsidies for new homeowners with a registered land title who qualify for the program. In 2023, the MLO helped 66 homeowners access government subsidies offered by Antioquia’s departmental government, permitting low-income residents to improve their flooring, bathrooms, and kitchen.

Since 2016, Colombia’s property registry authority, the Superintendence of Notaries and Registers (SNR) has worked with Municipal Land Offices (MLOs) to register and deliver thousands of land titles to owners all over the country. In this interview with

Since 2016, Colombia’s property registry authority, the Superintendence of Notaries and Registers (SNR) has worked with Municipal Land Offices (MLOs) to register and deliver thousands of land titles to owners all over the country. In this interview with  What objectives and challenges do you have in the SNR?

What objectives and challenges do you have in the SNR? How do Municipal Land Offices facilitate the work of the SNR?

How do Municipal Land Offices facilitate the work of the SNR?

In the Montes de María, a sub-region of the Colombian Caribbean region characterized by the abundance of its tropical dry forest, great stories of resilience have been consolidated thanks to the art of beekeeping.

In the Montes de María, a sub-region of the Colombian Caribbean region characterized by the abundance of its tropical dry forest, great stories of resilience have been consolidated thanks to the art of beekeeping. Everybody who has tasted it, says Tomasa’s honey is unparalleled. Tomasa Calonge partners with only the

Everybody who has tasted it, says Tomasa’s honey is unparalleled. Tomasa Calonge partners with only the  A public private partnership (PPP) in the honey value chain facilitated by Land for Prosperity will give Tomasa and over 680 beekeepers in the Montes de María region the chance to offer quality honey products to people across Colombia. The PPP, valued at more than US $1.1 M, is netting investments from a wide range of public institutions and supports 22 beekeeper associations.

A public private partnership (PPP) in the honey value chain facilitated by Land for Prosperity will give Tomasa and over 680 beekeepers in the Montes de María region the chance to offer quality honey products to people across Colombia. The PPP, valued at more than US $1.1 M, is netting investments from a wide range of public institutions and supports 22 beekeeper associations.