Summary

The artisanal and small-scale mining (ASM) sector has increasingly captured the interest of governments, international organizations, and private corporations because of its growing role in national economies and its impacts on society and the environment. The sector provides significant but generally poorly paid employment in difficult working conditions for the most marginalized populations in many developing countries. Numerous types of minerals are extracted in this fashion — gold, cassiterite, wolframite, colored gemstones, diamonds, and

even coal — and each value chain is characterized by particular specificities shaped by demand and geological factors. While a wide range of ASM practices occur throughout the world (Box A), the exploration, extraction, and trade of minerals have become controversial because of its occasional linkages with armed groups and negative impacts on environment and livelihoods at times of rapid expansion spurred by soaring world market prices. The production and commercialization of many of these minerals have fueled conflict in countries like Liberia, Sierra Leone, Angola, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), with property rights struggles often at the core of these conflicts. Fierce and sometimes violent contestation over the control of and access to mining sites has long characterized the resource tenure issues in the ASM sector. Through strengthening tenure security and clarifying property rights, these resource conflicts can be reduced significantly while also providing incentives for mitigating environmental impacts of this extractive sector.

BOX A: ARTISANAL AND SMALL-SCALE MINING

Artisanal and small-scale mining refers to mining by individuals, groups, families, or cooperatives with minimal or no mechanization, often in the informal and illegal sector of the market for minerals. “Artisanal mining” is often purely manual and on a very small scale, whereas “small-scale mining” is more mechanized and on a larger scale. While the terms are used interchangeably, both mining activities have low per capita productivity, require low capital investment, and employ much manual labor (Hentschel et al. 2002).

The first section of this issue brief reviews the largely under-recognized place of the ASM sector in national economies. Next, it describes briefly how ASM has been at the root of many resource conflicts in developing countries — particularly in west and central Africa. This is followed by a discussion of how the clarification of property rights contributes to the reduction of conflicts over mineral resources. By way of illustration, the USAID Property Rights and Artisanal Diamond Development (PRADD) project shows how the clarification of tenure arrangements can encourage greater transparency in the diamond-mining sector and incentivize rehabilitation of landscapes damaged by artisanal mining practices. The issue brief concludes with a short summary of the types of interventions USAID might consider for strengthening tenure and property rights regimes in the ASM sector.

The Place of Artisanal and Small-Scale Mining in the National Mining Sector

The International Labor Organization (ILO) and the World Bank Group estimate artisanal and small-scale miners number 20 to 25 million, including 6 million in sub-Saharan Africa (CICID 2005). Women and children figure prominently in artisanal mining: an estimated 650,000 women in 12 of the world’s poorest countries are engaged in the sector as well as 1 to 1.5 million children (World Bank 2008). The participation of women in artisanal mining in some countries can be significant, ranging from 10 percent of the workforce in Indonesia and 20 percent in the DRC to 50 percent in Ghana, Malawi, Nepal, and Lao PDR (Lahiri-Dutt 2007; World Bank 2012).

The ASM sector in many developing countries contributes an important stream of revenue for national economies. The place of ASM in a country’s gross domestic product (GDP) is difficult to estimate due to the largely informal and often illicit status of the sector. That said, gold production from the Tanzanian ASM sector in 1992 comprised an estimated 76 percent of all mineral export earnings from that country (Tesha 2000). Of the 582,000 carats of diamonds officially exported from Sierra Leone in 2006, 84 percent originated with artisanal and small-scale miners (Government of Sierra Leone 2011). Artisanal miners in the DRC produce an estimated 60–90 percent of that country’s minerals (Feeney 2010). In the Central African Republic (CAR), artisanal diamonds account for 40–50 percent of all export earnings, this despite the loss of revenue due to smuggling (USGS 2010; Hinton and Levin 2010). Artisanal mining also accounts for a large portion of national economies outside of Africa. In Mongolia, where mining accounted for 30 percent of GDP in 2007, ASM workers (approximately 65,000) outnumbered those in the formal mining sector, and the ASM sub-sector produced 10 percent of the mining sector’s total output (UNDP 2009). In addition, ASM provides a desperately needed source of income for people living in the poorest and most isolated areas, magnifying impact on local economies through its associated activities. Spinoff economic activities make four times more people reliant on ASM than the actual number of miners worldwide (World Bank 2008). The ratio is even more impressive in countries such as the CAR, where 68 percent of the population benefits from ASM while only 10 percent are directly involved in the sector (Hinton and Levin 2010).

The complex role played by ASM in national economies demonstrates the need for a nuanced perspective on the relationship between natural resources and development. Scholars and international organizations have increasingly recognized the positive role of artisanal mining in poverty reduction (Lahiri-Dutt 2006; Tshakert 2009). Some governments, such as Ghana and the CAR, rank support to this sector high in their current Poverty Reduction Strategic Statements. A more positive view of the role of diamond mining in national economies has emerged as part of the Kimberley Process Certification Scheme (KPCS), a voluntary international structure sanctioned by the United Nations aimed at regulating and monitoring the diamond value chain and thereby combating diamonds used to finance wars. In the KPCS Washington Declaration of November 2012, 75 country, civil society and industry representatives recognized that “economic security, formal regulation and sustainable development of ASM actors are necessary tools to bring rough diamonds into legitimate chains of custody” (Kimberley Process 2012). Instead of viewing ASM through the limited lens of conflict mitigation, the Washington Declaration urges governments to take steps toward artisanal mining development to improve livelihoods and legitimize the diamond economy, such as improving property rights policies and increasing access to mining inputs and finance.

Nevertheless, artisanal mining is accompanied by a host of social and environmental issues. The sector is typically characterized by low mechanization, inefficient production, intensive physical labor, minimal occupational health and safety standards, low salaries and incomes, and few environmental safeguards (Priester and Trappeniers 2010; Smilie 2010). Child labor is often used in places where there are few public health and educational services. Artisanal and small-scale miners are highly mobile in their search for employment within a country and across borders. Often this migratory labor force settles in far-flung places where governments fail to monitor mining and employment conditions.

The Artisanal Mining Sector and Resource Conflicts

The ASM sector is often cited as a factor that starts, escalates, and sustains conflict, with minerals sales having long been an important source of revenue for purchasing arms by governments, militias, and warlords. The African civil wars of the 1990s and early 2000s were largely fueled by insurgent forces who manipulated the artisanal mining sector to pay for arms and ammunition (Human Rights Watch 2009; Prunier 2011). Artisanal diamond, gold, coltan, and tungsten mining has contributed to the financing of conflicts in countries like Liberia, Sierra Leone, Angola, and the DRC. ASM can yield violence even without a civil war, as the abuses in the Marange diamond fields of Zimbabwe demonstrate.

Perhaps the most well-known of international responses to the illicit trade of minerals is the Kimberley Process Certification Scheme. The unprecedented mobilization of civil society groups, the UN Security Council, and the diamond industry in the late 1990s led to the creation of KPCS in 2003 as a strategy to curb the flow of “conflict diamonds.” A decade later, advocacy linked to appalling human rights reports from Eastern DRC led to the addition of Section 1502 to the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act in 2010, whereby US-listed companies that source tantalum, tungsten, tin, and/or gold from the DRC and neighboring countries must submit an annual third-party audited report to the Security and Exchange Commission proving their due diligence in ascertaining if their minerals are “conflict-free.” The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development also enacted voluntary guidelines in 2011 to ensure conflict-free supply chains for the same four critical minerals. However, the law does not provide the means needed to address governance failure in fragile states where mining, land, and other resource-based conflicts have exacerbated the rural-based violence and the migration of internally displaced persons.

BOX B: THE INTERFACE BETWEEN CUSTOMARY AND STATUTORY TENURE IN ALLUVIAL DIAMOND-MINING AREAS OF LIBERIA

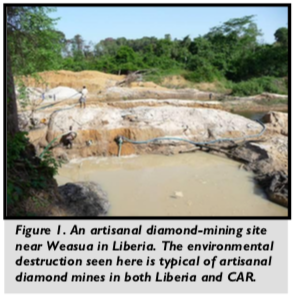

In the diamond-mining areas of Liberia, the Ministry of Lands, Mines, and Energy sells annual Class C mining licenses to any citizen willing to engage in mining activities using simple tools (excluding the use of bulldozers) for excavation and diamond extraction. Even though mining law requires rehabilitation of mined-out sites, the law is not enforced. Mining pits are simply abandoned.

In these mining communities, traditional authorities use customary tenure norms to govern access to land, trees, and water. One of these rules is that “stranger” diamond miners are prohibited from planting trees in the community. In Liberia, tree planting implies possession of long-term tenure rights and for this reason it is formally banned by residents. This principle is a disincentive to environmental rehabilitation in and around diamond-mining sites. In the end, diamond pits are abandoned while ownership remains unclear.

Local property rights systems largely affect the extent to which minerals can become a conflict nexus. When communities possess well established statutory and/or customary land rights, the presence of mineral resources does not necessarily undermine social harmony. In fact, case studies of artisanal mining in west and central Africa illustrate how well indigenous communities can extract rent from the newcomers or demand other forms of compensation for the use of the land (Mogba and Freudenberger 1998). Places where customary authorities are strong are particularly resilient to conflict. Some villages of northern Côte d’Ivoire resumed gold extraction and trade through traditional means in 2011 as soon as military commanders left the area to participate in the new government as if the decade of violence and ethnic strife had never existed. Once the military left mining areas, lands were clearly separated between agricultural and mining use, the rent to professional miners has become more transparent, and village monitoring teams now come regularly to arbitrate between the state and the miners (Elbow and Pennes 2012).

Other communities do not have the same longstanding traditions. In the southwestern provinces of CAR where the USAID PRADD project unfolded, many artisanal mining communities were founded in the 1960s and 1970s by diamond companies, which subsequently left or went bankrupt. The miners, who formed an ethnic patchwork without historical roots to the land, remained and grew in number. In this case, artisanal mining does create conflicts over site boundaries, land uses, inheritance rights, or market access among competing small traders. Even though few conflicts of this sort degenerate into violence, they can significantly affect social bonds and neighborly relations and negatively impact investment decisions. By having mining claims validated publicly based on geo-referenced site mapping, PRADD and the government introduced alternative dispute resolution practices that helped disputants come to mutually beneficial arrangements, and this reduced the risk of conflict. In a single year, the success of this “soft” method of conflict resolution linked to claims registration led to a decrease of diamond-related conflicts from 142 to 4 in one province in southwestern CAR (USAID 2011).

In another case, the two Kivu provinces of Eastern DRC are infamously known for decades of land and ethnic conflicts that have never been resolved. Problems linked to property rights existed well before the Rwandan genocide in 1994 and the rebellion starting in 1996 that led to the end of the Mobutu regime and the current era of chronic conflict. The civil war escalated local competition for control of mineral resources, undermining the tenure security and social resilience of several mineral-rich, rural communities (Autesserre 2006 and 2010). Mineral resources are now largely controlled by militant groups and rogue government forces. To prevent the emergence of violent conflict over surface and sub-surface resources, property rights need to be clarified. In this way, the social contract that binds local communities together can serve to mitigate the risk of conflict.

Resource Tenure in the Artisanal Mining Sector

Throughout the world, the long history of mining is characterized by struggles for access and control of mineral resources. Even a cursory review of the gold and diamond rushes of 19th century North America, Australia, and Africa illustrates how contentious property rights issues were at the heart of disputes pitting mining interests seeking access to subsurface resources against those holding multiple and overlapping rights to surface resources. This rich literature describes how mining interests have fought against those of indigenous peoples, cattlemen, and others with long-standing surface rights. Whether in the gold fields of 19th century California or in the oil-rich delta of present day Nigeria, these struggles are about who has rights of access to subsurface resources and the distribution of benefits found therein (Ali 2010; Collier 2007; Feinstein 2005; Mann 2011; Stewart 2009; Zinn 2003).

Reconciling Customary with Statutory Rights

ASM often occurs in alluvial deposits in and along rivers through the use of open pit digging and simple stream dredging techniques. Artisanal miners lack the technical means to mine deposits deep underground, and for this reason, they are forced to remove large amounts of overburden to attain the level of the mineral deposits. As a result of the mining operation, the land is severely altered (see Figure 1). This land is also often exploited by many other resource users like farmers, herders, and fishermen. These resource users possess a “bundle of rights” to the land: complex and overlapping rights to land, trees, and water resources often derived from long-held historical claims. These rights may clash with those holding sub-surface property rights.

While laws and regulations structure access to subsurface minerals in many developing countries, customary tenure arrangements are often more prevalent and dominant in determining sub-surface rights. “Statutory tenure” refers to those state institutions, laws, and regulations that govern access, use, and transfer of rights to both surface and subsurface resources. “Customary tenure” (sometimes known as “informal,” “indigenous,” or “traditional law”) often coexists with statutory tenure and property rights. Customary tenure governs seasonal access to resources and sets up nuanced agreements to deal with competing resource user groups such as gatherers, cultivators, and herders. Customary tenure arrangements are well defined for surface resources but rarely for sub-surface mineral resources. Tensions arise between land rights holders and artisanal miners, especially when the miners are migrants (the galampseys of Ghana, the ninjas of Mongolia, the garimpeiros of Brazil and Angola). Furthermore, customary tenure arrangements for sub-surface mineral resources are rarely equitable. Sometimes local communities impose heavy taxes on mining migrants; in other cases, miners backed up by powerful interests disregard customary rights and establish control over the mineral-rich land, such as in many areas of Eastern DRC (ACAC 2010; Autesserre 2010). Eastern DRC also offers multiple cases of sub-surface rights appropriation by the local elite to the detriment of community groups. Finally, not only are such local arrangements inequitable, they are often economically unproductive as well. In the absence of legitimate and informed third-party arbitrage, rights are distributed in ways that do not necessarily maximize everyone’s interest. A fair allocation of rights should balance historical practices with the principle of efficient use of land resources. The role of the government is necessary to shape local economic development without sidelining real and rooted practices on the ground. The process of reconciling customary with statutory rights requires a careful balancing act between preserving traditional social bonds while introducing new pathways to economic development.

While laws and regulations structure access to subsurface minerals in many developing countries, customary tenure arrangements are often more prevalent and dominant in determining sub-surface rights. “Statutory tenure” refers to those state institutions, laws, and regulations that govern access, use, and transfer of rights to both surface and subsurface resources. “Customary tenure” (sometimes known as “informal,” “indigenous,” or “traditional law”) often coexists with statutory tenure and property rights. Customary tenure governs seasonal access to resources and sets up nuanced agreements to deal with competing resource user groups such as gatherers, cultivators, and herders. Customary tenure arrangements are well defined for surface resources but rarely for sub-surface mineral resources. Tensions arise between land rights holders and artisanal miners, especially when the miners are migrants (the galampseys of Ghana, the ninjas of Mongolia, the garimpeiros of Brazil and Angola). Furthermore, customary tenure arrangements for sub-surface mineral resources are rarely equitable. Sometimes local communities impose heavy taxes on mining migrants; in other cases, miners backed up by powerful interests disregard customary rights and establish control over the mineral-rich land, such as in many areas of Eastern DRC (ACAC 2010; Autesserre 2010). Eastern DRC also offers multiple cases of sub-surface rights appropriation by the local elite to the detriment of community groups. Finally, not only are such local arrangements inequitable, they are often economically unproductive as well. In the absence of legitimate and informed third-party arbitrage, rights are distributed in ways that do not necessarily maximize everyone’s interest. A fair allocation of rights should balance historical practices with the principle of efficient use of land resources. The role of the government is necessary to shape local economic development without sidelining real and rooted practices on the ground. The process of reconciling customary with statutory rights requires a careful balancing act between preserving traditional social bonds while introducing new pathways to economic development.

Customary Rights and Large-Scale Mining Concessions

Clashes over state allocation of mining rights between large-scale mining interests and artisanal miners are numerous and sometimes violent. Governments in most developing countries reserve and allocate rights to all subsurface minerals. Historically, the state has claimed rights to minerals as part of a “social compact” with its citizens. The government allocates mineral rights, or mining concessions, to individuals and companies equipped with the means to extract the resource. The state taxes these mining operations and often claims publicly to allocate these royalties for social services and public infrastructures. Unfortunately, clashes are inevitable. People forfeiting rights of access to sub-surface resources always question whether tax revenues indeed return to the local community. The root causes of civil wars, such as those of west and central Africa, can be attributed to the failure of the state to distribute fairly royalties from mineral extraction (Collier 2007; Snyder and Bhavnani 2005).

Mining laws and regulations in most developing countries usually require compensation for people deprived of their surface rights. In theory, large-scale mining operations can be forced by governments to pay compensation to rural communities deprived of their surface rights. Yet in practice, adequate compensation is rarely paid, is of insufficient value, and often not distributed fairly. Poor valuation procedures are often cited as the leading factor in disputes over compensation. These disputes over compensation hide a deeper confrontation. Indigenous communities are not only displaced by large-scale mining ventures, but also by non-resident artisanal and small-scale miners invading the traditional territories of resident populations. Not surprisingly, affected communities often resent both large- and small-scale mining. In some cases, these communities never see the economic benefits of the mining but instead lose access to precious land and resources that are integral to their survival.

In countries where mineral resources and the mining sector contribute significantly to national economic output or provide an important source of revenue to the government, the state may strongly assert and exercise its claim to subsurface rights, bringing it into conflict with a dispersed, impoverished, and poorly organized class of artisanal and small-scale miners. Governments usually prefer to lease rights of exploration and mining to large-scale parastatal and private firms with sufficient financial and technical means to mine minerals located deep in the ground. Leases and concessions to mining areas in these cases are usually well specified. However, shallow deposits, such as those found in alluvial zones, are a source of much conflict. Large-scale mining ventures may obtain concessions to mine these deposits with heavy equipment. Yet artisanal and small-scale miners may already be extracting mineral resources in these areas. Equipped with little more than rudimentary tools and a drive for money, miners compete directly for access to the subsurface claims. The history of ASM is replete with cases of clashes between well-financed corporate interests armed with legally recognized permits and the large numbers of individual miners holding no legal documentation to their claims. In fact, the most contentious issue the KPCS ever faced since its creation dealt precisely with a massive crackdown and shooting of artisanal miners in the Marange field, a concession previously allocated to the Zimbabwe Mining Development Corporation, in November 2008. Building complementary relations between the large-scale and artisanal mining sector will be a long process of negotiation (International Council on Mining and Metals [ICMM] 2010).

Tenure and Artisanal Mining in Fragile States

When the state is unable to assert its authority as exclusive arbiter of land and mining rights, has failed to fulfill its obligations to citizens in sharing benefits from mining, or is not recognized as a legitimate claimant to land and mineral resources, other forms of tenure may dictate how mineral resources are discovered, extracted, and traded. In weak and fragile states, customary tenure often governs access, use, and transfer of sub-surface rights. Traditional authorities sometimes set up rules and mechanisms to govern how mineral resources are to be extracted in a particular locality. Warlords and rebel groups take over these functions in other cases. As well documented in the CAR, the customary tenure authorities can be remarkably effective in enforcing rules of access to artisanal mining areas (Mogba and Freudenberger 1998). In the situations where neither government nor traditional authorities are able to design and enforce rules governing access to sub-surface resources, the mining areas can turn into de facto open access situations. Since no authority enforces access and use of either surface or sub-surface resources, a free-for-all ensues whereby the most powerful, and usually well-armed, dominate. The losers are often those holding bundles of rights to the immediate surface lands but downstream people are also affected by water pollution, siltation, and other impacts of mining operations. Extractive resource mining — be it oil extraction in the Niger Delta of Nigeria or alluvial diamond mining in the CAR — present numerous legal and practical complexities for policymakers seeking to balance statutory with customary tenure.

Approaches to Clarifying Property Rights in the Artisanal Mining Sector: Pradd Car and Liberia

The Clean Diamond Trade Act authorized the U.S. Department of State to work closely with USAID to finance projects to improve compliance with the KPCS. From 2007 to 2013, the PRADD project worked to clarify and strengthen the property claims of artisanal miners in diamond-mining areas and brought them into full compliance with the law. The objective of the project was to increase the number of diamonds entering the formal chain of custody while also improving the livelihoods of artisanal diamond-mining communities.

The PRADD project has implemented activities in the CAR, Liberia, and Guinea, as well as Cote d’Ivoire at the policy level.1 The project worked with local communities and government to establish clearly defined property rights for artisanal diamond miners. Clarification of rights is intended to assist miners to defend mining claims vis-à-vis the state and other interests. Project evaluations showed that miners who received “certificates of customary rights” were investing their labor to rehabilitate degraded land within their claims and put it to other productive uses, such as small-scale fish production and gardens (USAID 2012).

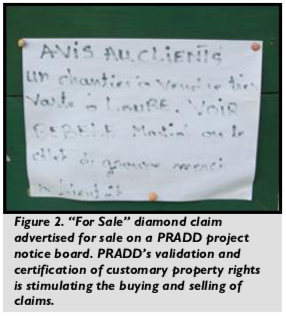

They were also more capable to resolve local conflicts: in one province of intervention, the mining police recorded that the number of diamond-related conflicts plummeted from 142 to 4 in only one year. With the help of PRADD, the mining ministry issued 2,849 certificates in the pilot sites. The focus on strengthening land rights of artisanal and small-scale miners also led to important environmental benefits. By December 2012, 654 artisanal mining sites were rehabilitated with the technical assistance of the PRADD project. The project provided technical and organizational training in ways to regenerate the land through gardening, tree planting, and fish pond construction. Experience with implementing the project suggests that clarification and recognition of the tenure situation in mining communities can indeed generate many benefits for ASM. Finally, there appeared to be a land market developing due to the PRADD process and the issuance of certificates of customary rights signed by the CAR government (See Figure 2).

They were also more capable to resolve local conflicts: in one province of intervention, the mining police recorded that the number of diamond-related conflicts plummeted from 142 to 4 in only one year. With the help of PRADD, the mining ministry issued 2,849 certificates in the pilot sites. The focus on strengthening land rights of artisanal and small-scale miners also led to important environmental benefits. By December 2012, 654 artisanal mining sites were rehabilitated with the technical assistance of the PRADD project. The project provided technical and organizational training in ways to regenerate the land through gardening, tree planting, and fish pond construction. Experience with implementing the project suggests that clarification and recognition of the tenure situation in mining communities can indeed generate many benefits for ASM. Finally, there appeared to be a land market developing due to the PRADD process and the issuance of certificates of customary rights signed by the CAR government (See Figure 2).

Benefits of Clarifying Property Rights in the Artisanal Mining Sector

National policy reforms on land tenure should promote the clarification of statutory and customary sub-soil rights in parallel with similar initiatives around overlapping surface rights. While many models of rights clarifications in the artisanal mining sector are being tried throughout Africa, Asia, and Latin America, these reforms need to consider the interface between complex bundles of rights to surface resources and those below the ground. These new approaches seek to confront the complex challenge of integrating statutory with customary tenure. An interesting case is that of Ghana. The Minerals and Mining Act of 2006 provides strong incentives for mining companies to negotiate with all customary landowners and pay fair compensation. Since customary rights to land are recognized by the land laws of Ghana, mining companies are required to negotiate with all owners whether the interests are registered or not. The government and mining companies are required to map all the untitled but verifiable land rights claims. The legal principle is based on the precept that the mining company is the intruder into the territory of the local community. Fair compensation must be paid to registered customary owners of land at market value (Antwi 2011; Hilson and Banchirigah 2009). Even in the civil law countries of west and central francophone Africa, fair compensation must in principle be paid to occupiers of the land.

While the process of rights clarification can be complex, benefits are starting to become apparent in a few cases, like that of the PRADD project sites in the CAR. That said, benefits from rights clarification will not occur until policy measures, legislation, and public education are put in place to determine who controls and manages surface and subsurface rights. Indeed, the policy challenge is to marry statutory and customary tenure suited to the cultural and economic conditions of particular countries.

Rights to Land Strengthens Chain of Custody

The recording of mining claims in registries and other databases is an essential component of the process of strengthening the chain of custody for mining operations. As is now required by the KPCS and suggested by new legislation (such as Dodd-Frank), the monitoring of the flow of minerals from the point of extraction to the point of export into the international economy implies knowing the origins of the mineral. Linking production statistics with certification of possession of claims often goes hand-in-hand. Legal exports originating in the PRADD provinces of intervention in the CAR increased by 450 percent between 2010 and 2012. National exports increased by 21 percent during the same period. As is now apparent through the PRADD project, miners holding claims certificates are more likely to record their production statistics because they are certain to hold on to their valuable claims. This makes it more feasible for the government to monitor and certify the flow of diamonds from the remote point of extraction to the point of export, to date one of the weak points in the Kimberley Process system.

BOX C: STRENGTHENING ASM CAN IMPROVE LIVELIHOOD OPPORTUNITIES AND FOSTER SUSTAINABLE LAND-USE PRACTICES

In the Central African Republic, Ms. Berthe Yadjo struggled to feed her children using the money she earned from artisanal mining of three claims she inherited from her deceased husband. In February 2010, Ms. Yadjo converted two of her three pits into fishponds and in August reaped her first harvest of fish. In December, the US Embassy invited Ms. Yadjo to a women’s entrepreneurship workshop in Bangui. There she gained invaluable knowledge and stature in her community and began to provide investment training to assist other women to build their own fishponds. Early in 2011, Ms. Yadjo bought an exhausted mining site and rehabilitated it into her third fishpond.

Through its approach of validating customary property rights and diversifying mining community income, PRADD is helping repair the environmental damage caused by artisanal mining by using income-generating schemes.

Clear Tenure Encourages Investment

Clear tenure lowers the risk of investment for local brokers and miners while improving the legal status of artisanal miners. This clarification in turn increases profits and legal sales and is a precondition for attracting investors. Likewise, local communities and corporations can establish creative arrangements that allow mining operations and establish compensation packages ranging from cash payments to legitimate owners to the provision of social services and infrastructure development. Admittedly, this negotiation is difficult even if all the correct laws and precedents are in place. Legal training by civil society organizations can play a role in strengthening the capacity of artisanal mining communities to negotiate contracts (Hentschel et al. 2002). In addition, if all parties live up to their commitments, the investment climate will improve greatly, since investors will perceive less risk of resistance and sabotage of their mining operations.

Clear Tenure Encourages Environmental Rehabilitation

Clarifying and recognizing the rights of miners to continue using land from which they have extracted minerals encourages rehabilitation and conversion to other economic uses. The PRADD project in the CAR found that allocation of claims certificates recognizing customary property rights to mining areas served as an incentive to rehabilitate mined-out pits (see Box C). With a claims certificate in hand, artisanal miners are reassured that their investment in converting open pits to other uses like fishponds, gardens, or orchards will indeed bear fruit. Pioneering environmental rehabilitation projects in the diamond-mining areas of Sierra Leone similarly stressed the need to strengthen long-term property rights to guarantee that benefits reach those investing labor in regenerating the land (Baxter 2009).

Allocating Secure Tenure Rights Reduces Likelihood of Conflict

Clarifying and securing property rights is essential for reducing the potential destabilizing effect of ASM by offering a framework to negotiate and optimize the resource needs of ASM miners, governments, and other stakeholders. In addition, at a more local level, the process of clarifying tenure arrangements is in itself a form of dispute resolution or prevention since it can reduce conflicts over resource rights and boundaries.

Clarification of Rights Helps Inform Royalty Payments

Mining companies and artisanal miners alike are often required by law to pay license fees and royalties. By having clear property rights and knowing who is mining where, it becomes clearer where such royalties should be reinvested. Such transparency and legitimacy can allow miners and local authorities to play a watchdog role and thereby ensure that tax revenues linked to mining are actually benefiting their communities. As witnessed in Sierra Leone, making tax payments back to communities for social development contingent on legal behavior is an important driver toward legalization (Hinton and Levin 2010).

Conclusions and Recommendations

International development agencies should consider a range of flexible interventions to strengthen property rights in the artisanal mining sector. Careful consideration of the local cultural, political, and tenurial context in which ASM occurs is essential in designing interventions that unleash the economic potential of the sector. However, an approach suitable in one area with a specific set of stakeholders may not be appropriate for another situation. Despite the need to adapt to local realities, the following general principles and practices are worth highlighting.

Develop an International Policy Framework for ASM

To date, ASM policy frameworks and regulatory mechanisms remain poorly articulated at the international level. Despite the coordination efforts of the Communities and Small-Scale Mining (CASM) initiative — a multi-donor program created in 1995 and supported by the World Bank — no systematic guideline has addressed the scope of the challenges and opportunities of ASM at large. The KPCS Washington Declaration is the most advanced policy endeavor in this domain, but it focuses only on diamond mining. The donor community should foster the development of policy guidelines for an internationally coordinated approach to ASM, bearing in mind the extensive policy positions previously developed around large-scale mining. These include the Safety and Health in Mines Convention of the International Labor Organization (Convention 176 of 1995), the Equator Principles (2006), the Sustainable Development Framework of the International Council on Mining and Metals (completed in 2008), and the Sustainable Development Framework of the International Finance Corporation (completed in 2012).

Clarification of Customary Tenure

International guidelines like the Committee on World Food Security’s Voluntary Guidelines on the Responsible Governance of Tenure of Land, Fisheries and Forests in the Context of National Food Security (Voluntary Guidelines) have developed policy statements on measures to be taken to clarify tenure and property rights throughout the world (http://www.fao.org/docrep/ meeting/025/md708e.pdf). Policy and issue briefs regarding ways to recognize and clarify surface tenure rights (land, forests, pastoralist zones, and customary tenure) are available on the USAID Land Tenure and Property Rights Portal (www.usaidlandtenure.net). This issue brief argues that the recognition of customary tenure for surface resources facilitates the negotiation of subsurface mining rights. Fair compensation for land used for mining and subsequent royalty payments to local communities holding historical rights starts with an understanding of who owns the bundle of surface rights in a particular territory.

Support Government Efforts to Distinguish Different Types of Rights and Rights Holders

Where individuals and groups do not hold land privately, there may be confusion and/or conflict over who holds the rights to land and minerals in the exploration, extraction, and post-mining stages. Particularly in areas where people are interested in the rehabilitation of land, governments (in consultation with traditional authorities) should define and document the responsibilities and long-term use rights to the land from which minerals are extracted. New policies and laws may be needed that clarify tenure of surface and sub-surface resources. Important considerations include whether land reverts to an original “owner,” whether it is retained by the miner, or whether it becomes the property of the state. These considerations affect whether the land is rehabilitated and put to other uses. Donor agencies can provide technical assistance to governments to help them work with stakeholders to clarify rights recognition and provide technical assistance for environmental rehabilitation of ASM sites.

Support Formalization of the ASM Sector

Experience from the PRADD project suggests the importance of recognizing and recording customary property rights and physical delineation with modern tools like GPS technology. “Formalization” of ASM activity in the vicinity of industrial scale mining operations can help identify rights so that ASM and industrial operations can coexist without conflict.2 After such rights are assigned, they should be transferable or used as collateral for credit to develop a community asset base. At the policy level, the government can support formalization by recognizing customary tenure, but also by increasing access to licensing offices, introducing mobile licensing teams, decreasing formalization costs, or increasing duration of land and subsurface claims. The Washington Declaration of the Kimberley Process lists other innovative actions that would inspire policy makers.

Design and Implement Seasonally Appropriate Income Diversification and Livelihood Interventions to Complement Property Rights Clarification

Development programming for livelihood diversification and poverty alleviation often focuses on dry season activities like off-season gardening or road rehabilitation. However, dry season investments of labor in development projects often conflicts with labor-intensive ASM activities that occur throughout the dry season — a time when most digging occurs in dry riverbeds and swamps. Livelihood diversification in mining areas should focus on activities that do not compete with ASM. Other livelihood diversification options can focus on women members of mining households, for example, developing skills in ration cooking, fuel retail sales, and other economic activities closely linked to artisanal mining.

Develop Systems for Registering and Tracking Mineral Extraction and Revenues and Allocating Expenditures

Governments can help alleviate poverty in areas dependent upon ASM by investing revenues from ASM taxation back into the producing communities, and supporting activities that promote local economic diversification. Governments should manage mining revenues in a transparent and equitable manner and strike a balance between national and local development needs. Effective systems for monitoring production and tracking the origin of minerals are essential if localities are to receive a proportion of the revenue generated from mineral extraction in their areas. When tax revenues are generated from large mining operations, it may be appropriate to invest these funds in roads and other public infrastructures of regional and national scale. However, the dispersed and small tax revenues collected from artisanal and small-scale miners can be used for development of communities where ASM extraction occurs, to foster accountability of the government and greater trust between local communities and state authorities. Mining development funds build popular support as long as the local communities retain oversight powers. Setting up institutions with sound financial management methods that are transparent and accountable is also essential; in Sierra Leone and the CAR, tax revenues set aside for community development have generally not reached the community level due to weak management of trust funds (Levin and Turay 2008; Maconachie 2009).

Increase Cooperation Between ASM and Industrial Miners and Improve ASM Competitiveness

Greater investment and smart incentives can increase cooperation between ASM miners and industrial mining operations. This can in turn benefit producers as well as the state institutions charged with governing mineral rights (Preister and Trappeniers 2010). Government should accommodate both ASM and industrial miners in its allocation of concessions, enabling a diverse arrangement of use rights that maximizes the potential benefits from the sector (ICCM 2010). Once artisanal and small-scale miners are organized in some institutional structure (e.g., cooperatives, associations, and collaborative work groups) extension services can be more easily provided to facilitate access to credit, markets, and other technical services.

Support and Implement Models for Monitoring and Regulating Activity and Mediating Disputes

Donors should support independent dispute resolution mechanisms that focus on ASM miners and the communities in which their activities occur. Local dispute resolution procedures need to be developed in culturally appropriate ways and be recognized by the state. Dispute resolution practices must respect the law, particularly in the domain of women’s rights. The establishment of local codes of conduct and producers’ groups responsible for self-imposed regulation can utilize social pressure to enforce agreed-upon standards of “good mining practice.” Where foreign concerns engaged in industrial mining are part of the conflict, external monitoring of foreign interests and arbitration through third parties and civil society groups, such as the Mining Ombudsman Project, may help reduce conflicts (Oxfam 2010).

Introduce Land Use Planning in Property Rights Interventions

Land tenure clarification and economic diversification should be accompanied by community involvement in land use planning for present and future uses. Such efforts are a precondition for sustainable use of resources in a given area, especially after mineral resources are depleted. The intervention should include provincial and national government as much as possible to balance the economic interests of all stakeholders.

Address the Complex Problem of ASM Financing through Public-Private Partnerships

Property rights interventions alone will not curb the illicit financing of ASM. Alternative financing schemes can include the provision of capital investment or quality equipment, preferably after miners are organized into cooperatives and/or associations. For instance, USAID already encourages corporate stakeholders to develop strategic development alliances in the industrial mining sector (USAID 2010) and could adapt such models to the ASM sector, such as by developing a supply chain focused on ethically sourced and traceable artisanal minerals.