Introduction

It makes sense to think that the lack of an adequate document validating property rights in land is a barrier to credit access and that programs that provide people with title to their land will, therefore, lead to an expansion of credit access. This is especially true for those who have experience in a developed country like the United States, where larger loans are typically based on the use of real estate as collateral, and where banks require properly recorded records of real property ownership (whether deed or registered title) in order to complete a loan transaction. Even in such settings, however, other significant factors (such as income level, availability of credit in the market, and viability of the borrower’s business plan) determine whether or not one obtains a loan and what the terms of that loan are. Yet a simplistic belief that having a land title will make credit available to farmers and other poor entrepreneurs, helping them move out of poverty, has shaped expectations of programming to improve land rights.

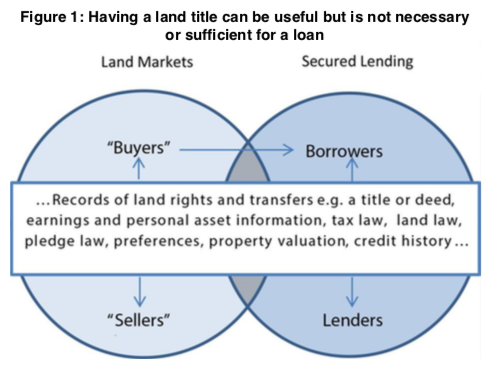

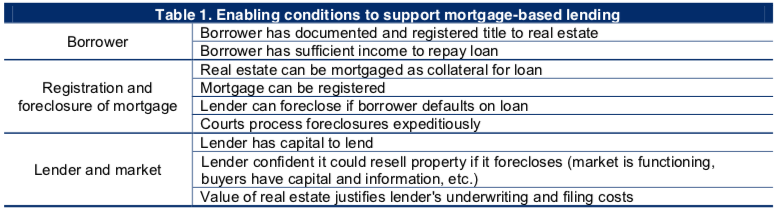

While a high proportion of land in developing nations lack formal documentation of rights and many land users have insecure rights to land, Figure 1 and Table 1, shown on the following page, show the many elements considered in decisions around land and credit markets and the use of land as collateral for a loan. Reliance on titling alone to promote greater access to credit creates a hope that will largely be unmet.

One of the main surprises, and some would say disappointment, of many existing impact assessments of land property rights reforms to date has been the failure to find much significant credit supply response (The Economist 2006) as advertised by some of the key proponents of property rights reforms including Hernando de Soto and others (de Soto 2000). (Conning and Deb, 2000, p. 36)

Some authors even suggest that promotion of land titling programs based on this expectation contributed to investment in unsustainable institutions for improved land records (Ali, Deininger and Goldstein 2011).

Land Titles: One Tool within a Property Rights System

A land title is only one type of record of property rights to land. Land rights can be validated in simple receipts, in deeds, in leases, and even through oral testimony. Land records are only one piece of the property rights system. Additionally, there are policies, laws, institutions, and practices that together define, assign, and enforce land rights and govern the use and transfer of rights in land. These can be statutory and/or customary, and both have validity.

Some also wonder whether it is even important to care about making reforms that would allow credit access to expand with land titling. In other words, should the conversation be focused on secured lending, in the context of poverty reduction? For many poor farmers whose income level is so low that they seem trapped in a vicious cycle of poverty and vulnerability, the loss of land and meager assets is too huge in terms of survival to invite credit risk by pledging collateral to a formal lender. On the other side of the equation, the assets that these households have are too small in value and might face cultural barriers to resale making the costs to a lender in doing business with such clients unjustified. Perhaps that is why for the poor and even many of the not-so-poor throughout the world, financial capital tends to be obtained through informal borrowing, gifting, and bequeathing within families or communities; through microfinance loan products that rely on group lending as a way to manage lender risk; pledging of movable assets, such as a cow; supply-chain lending for farmers and small entrepreneurs; or other loan products that do not require the pledge of land or real estate. While that is the reality in many Lesser Developed Countries (LDCs), at some point, these types of finance can become limiting in terms of the amount of capital and are not optimal in relation to the terms of credit (duration and interest rate, for example, or individual versus group borrowing). Therefore, in the longer view of growth and poverty reduction, it is important to consider secured lending as part of a continuum of financial services that meets the changing needs of households and businesses.

This brief will walk through the geneses of the simple belief that land titling will cause credit access to increase and look at the empirical literature examining the actual impacts of land titling in a variety of contexts. Based on a summary review of the literature, this brief shows why it is unlikely for land titling alone to increase credit access in the vast majority of places where USAID is engaged in development efforts. This brief also highlights some contexts where it is more reasonable to expect that getting the property rights piece of the finance equation right will increase access to credit.

“Giving you and so many Afro-Colombian communities title to this land is part of ending this nation’s long conflict. It gives you a new stake in a new Colombia.”

President Obama, April 15,2012, Plaza San Pedro, Cartagena, Colombia

In contextualizing the empirical relationship between title and credit, and appreciating the reality that land titling might not bring about better access to credit, it is important not to lose sight of the significant other reasons to continue to invest in improving the security of land rights and the efficiency of land transactions through improving laws, institutions, and practices. There is both quantitative and qualitative evidence from around the globe that supports the view that improving land rights will have positive impacts for economic growth (e.g., through motivating greater investment and production and increasing the value of land in markets), for socio-economic development (e.g., through empowering women and improving household well-being), peace and stability (e.g., by recognizing that disputes over land rights and grievances about inappropriate takings of right are often kindling for widespread conflict and civil war), and environmental sustainability (e.g., through incentives for longer- term investment in forests and soils and through improved approaches to climate change management).

From Theory to Practice: How Perspectives on the Link Between Land Titling and Credit Access Evolved

Many have heard of Hernando de Soto and his book, The Mystery of Capital. Fewer are familiar with the work, put forward prior to de Soto’s book, of Gershon Feder and colleagues on the impact of land titling in rural areas of Thailand. After this work, academics and land tenure experts began to believe that land titling contributed to an expansion in access to credit for the rural poor and began emphasizing this outcome as justification for land titling programs. Yet they did so without paying attention to some of the contextual details noted by these authors that affect the conclusions and how relevant they are to other places.

For example while showing that titling significantly improved farmer access to credit, they also point out that evidence from three provinces in Thailand demonstrates that large-scale farmers with higher land values and/or more capital are more likely to use land collateral, as compared with small-scale farmers, and this would mean that targeting land titling to the rural poor is much less likely to yield more access to credit than it would for the more well-off farmers.

In 2000, de Soto’s The Mystery of Capital argued in relatively simple and popular text that a key to economic citizenship is a paper record of property rights to land, and stressed the turning of “dead capital” into live capital, largely mediated by the access to credit that would flow upon titling.

[The poor] hold these resources in defective forms: houses built on land whose ownership rights are not adequately recorded, unincorporated businesses with undefined liability, industries located where financiers and investors cannot see them. Because the rights to these possessions are not adequately documented, these assets cannot readily be turned into capital, cannot be traded outside of narrow local circles where people know and trust each other, cannot be used as collateral for a loan, and cannot be used as a share against an investment (de Soto 2000, 5-6).

It is property documentation that fixes the economic characteristics of assets so that they can be used to secure commercial and financial transactions and ultimately to provide the justification against which central banks issue money. To create credit and generate investment, what people encumber are not the physical assets themselves, but their property representations—the recorded titles or shares—governed by rules that can be enforced nationwide (de Soto 2000, 63-4).

Extralegal asset owners are thus denied access to the credit that would allow them to expand their operations—an essential step toward starting or growing a business in advanced countries. In the United States, for example, up to 70 percent of the credit new businesses receive comes from using formal titles as collateral for mortgages (de Soto 2000, 84).

The success of the book, de Soto’s popularity, and his access to high-level officials around the globe helped foment a widespread belief among leaders (both within developing nations and within international development agencies and organizations) that land titling is a kind of silver bullet to open access to credit. In embracing this idea, such leaders ignored some of the points de Soto raised about broader law and institutional reforms that contribute to the formality of property rights.

In a more academic arena, Boucher, Barham, and Carter (2005, p. 210–211), explain the assumed causal relationships implicitly linking title to credit as follows:

- Formal lenders with limited information require collateral to limit risks around default.

- In the case of Latin America, the liberal view perceives the critical problem to be a lack of titling which prevents the full collateralization of the main asset of the poor.

- Thus, “granting and registering freehold titles,” based on the perspective “that titling should activate credit markets via both supply and demand effect.”

- The supply side is affected by farmer’s ability to provide collateral, while increased tenure security and the farmers’ willingness to invest increases credit demand.

- In theory, therefore, the linkage spurs efficiency and equity.

As a reaction to this type of thinking, some authors began disputing the likely impact of land titling per se and pointing rather to a more sophisticated understanding of finance and to the non-simplistic but vital role that effective property rights plays in financial market development (Arruñada 2010; de la Peña et al. 2004; Fort 2007). Fleisig and de la Peña (2003a and 2003b), for example, argue that land titling will do little to expand credit, and provide a good review of what comprises an enabling environment for real property to successfully leverage credit. Sanjak (2003) points out that land titling addresses only a piece of the broader reforms to property rights necessary to create a good environment for credit. Other authors also point to the need to look at other failures in credit markets beyond the lack of formal land titles, including Skees (2003); Boucher, Barham, and Carter (2005); and Payne et al. (2008).

However, we also need a legal framework for secured transactions to use those assets as collateral for loans. That opens another large field of law, which is paved with problems in developing countries. These papers discuss problems in the legal framework dealing with property rights, including secured transactions, and how they limit access to credit. The Ukraine papers and draft law further explore options for laws on real estate collateral modeled to the more advanced framework for secured transactions in movable property (de la Peña, et al. 2004).

In summary, land tenure reform in many contexts will not improve access to credit because gaps exist in the readiness of financial markets. For example, the people and businesses targeted to receive land titles are not bankable (their income is too low or their business plan is not financially viable), no supply of capital or loan products are available to the market segment, or the real estate market or social issues limit pledging or enforcement of pledges upon default. The following section reviews studies that investigate the linkage in practice between land titling and credit, and from these we will see how such gaps lead to partial or segmented credit responses, and also that other contextual factors also matter, such as the level of local conflict.

What the Empirical Evidence Shows About the Relationship Between Titling and Credit

Against the backdrop of reasoned enthusiasm and a passionate interest among the international development donor community in expanding land titling, a larger body of literature emerged that examines empirically the link between land title and credit. This literature shows the limitations of theory as applied in practice in a world where markets for land and for capital are not competitive and not well developed (there are problems at multiple touch points shown in Figure 1). In fact, in some places these markets are still nascent and of limited scope, at least outside of customary or informal transactions.

Some studies show positive results, but most of these also clearly point to particular contextual factors that affect if and for whom a credit market response emerges:

- Carter and Olinto (2003, Paraguay) and Mushinski (1999, Guatemala) identify credit impact only for medium and large farms.

- Byamuguisha (1999) affirms the linkage between title and access to credit in Thailand, albeit only in the long run.

- McLaughlin and Palmer (1996, urban Peru) and Field and Torero (2008) find an impact only in lending from the state bank.

- Dower and Potamites (2005, Indonesia) show that a title does not in and of itself unleash access to credit, but rather provide one signal among many regarding the borrower’s creditworthiness.

- Goyal and Deininger (2010, India) show that computerizing the land registry (not titling) had an effect on borrowing in urban areas, but not in rural areas.

- Karen Macours (2009, Guatemala) illustrates how the effect of land titles on plot use and credit access varies with the prevalence of conflicts and different types of conflict resolution mechanisms.

Even in Feder’s early work studying the impact of titling in Thailand, the conditional nature of the impacts were noticed. In all three provinces studied, squatters have significantly lower borrowing from institutional sources than farmers with secured land rights. However, in one of the provinces with a well-developed informal credit market with ample credit supplied by traders “who base their lending decisions on their personal familiarity with farmers rather than requiring collateral… differences in credit availability between tilted and untitled farmers are not substantial… and differences in capital formation are less significant” (Feder and Onchan 1987, p. 318–319).

A more nuanced view of the impact of titling is highlighted in his more recent work (Feder and Nishio, 1998), which concludes that titling is likely to be most effective where there exist robust formal financial markets, incentives for investment in land (such as proximity to markets and good quality land), demand for land transactions, and an enabling regulatory framework for land registration.

There are also many studies, however, that fail to detect any actual impact of titling on credit. Some of the more known papers include Boucher, Barham, and Carter (2005, rural Honduras); Zegarra and Aldana (2008, rural Peru); Payne, Durand-Lasserve, and Rakodi (2008); Markussen (2008); Roth et al. (1994, Uganda); Deininger and Feder (2009); Torero and Field (2005, rural Peru); Brasselle, Gaspart, and Jean-Philippe Platteau (1997, rural Burkina Faso); Deininger and Chamorro (2004, rural Nicaragua); and Galiani and Schargrodsky (2006, peri-urban Argentina). Some of these authors also refer to the state of credit markets, similar to studies mentioned in the previous section, in explaining the lack of a credit impact from land titling. For example, in the research of Brasselle, Gaspart, and Jean-Philippe Platteau (1997), the authors find that, “Since formal credit and land sale markets do not exist in the survey area, one of the three presumed effects of individualized tenure on investment incentives— namely the collateralization effect—is prevented from operating” (2002, p. 400). The authors likewise mention research in Andhra Pradesh, India by Pender and Kerr, which found that land right (as measured by its transferability) had scant effect on credit, “presumably because of the scarcity of formal credit sources in the survey areas” (p. 400-401). Additionally, a range of qualitative papers suggest the same lack of a connection between titling and credit.

Both observations of the conditions and limitations to credit impacts and the studies which did not detect such an impact led to the critique now accepted widely among academics and practitioners that titling is not sufficient to gain access to collateral-based credit. Most will say that land titling is not a panacea and that we need to be very cautious in expecting title to produce an impact on credit access, especially for the rural poor. In this context, many of the Economic Rate of Return (ERR) used by the Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC) to determine economic viability of land right projects (which can be seen at www.mcc.gov) do not include a projected credit impact. The notable exceptions are Lesotho and Mongolia urban property regularization activities, both contexts where assessments showed that important facets of the development of credit markets were already emerging (i.e., these are contexts where it is reasonable to expect such interventions to have an impact on credit access).

Even with this strong view as to the limitations of titling on credit access, it should be remembered that a well-functioning system of property rights–including but not limited to records such as a land title–is necessary for a well-functioning system of secured lending to emerge based on pledge of real immovable property such as land and housing. Basically, the existence of legal clarity about land tenure, formal record of property rights, effective contract enforcement and dispute resolution mechanisms, and efficient administrative systems in place for recording interests in property allow lenders to assess and price risk, reduce transaction costs in doing a loan deal, and enforce their rights in the event of loan default.

Conclusion

In sum, there is fairly universal agreement among experts that while formal documentation of land rights does matter in the broad scheme of financial sector development, it is not sufficient to bring about more immediate access to credit, especially for the rural poor. There are many other pieces (both in terms of land rights and in terms of financial market development) that need to be in place. Unfortunately, while many or even most land tenure and property rights (LTPR) practitioners have long left aside the simple expectation that issuing land titles will bring credit access, this expectation is still all too often heard among policy and programming decision makers, leading to continued unrealistic expectations and insufficient grasp of the multiple ways in which enhanced tenure security and property rights systems can affect development outcomes–economic, social, and environmental.

There are also arguably some locations where the economic, demographic, and social dynamics are creating a space where strengthening the integration of land and financial capital could be a worthwhile development intervention. These include areas of expansion of irrigated agriculture, areas of improved urban infrastructure, peri-urban agriculture and non-agricultural modernization, and expansion of tourism. However, it should now be clear that in the vast majority of places where USAID programs operate, there should be no expectation that land titling will produce greater access to credit. Moreover, in those locations where a focus on development of lending based on use of land as collateral is a good idea, it is still important to keep in mind that effective land rights are only one piece of what needs to be done and establishing effective land rights often requires more than or different interventions than land titling.

The main idea presented in this brief has two components. First, when considering if land titling is a good investment in relation to expanding access to finance, one should ask “for whom, where, and what other requisites need to be in place?” Second, improving land rights and access to land will have important economic, social, and environmental benefits apart from credit access and that these benefits need to be fostered through appropriate interventions, as described in the opening of this brief.