Overview

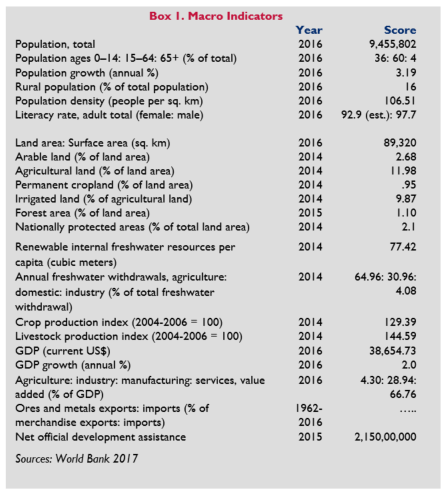

The Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan is located in the heart of the Middle East, northwest of Saudi Arabia, south of Syria, southwest of Iraq, and east of Israel and the Palestinian National Authority. Jordan has access to the Red Sea via the port city of Aqaba, located at the northern end of the Gulf of Aqaba. Amman is the capital and largest city. The country’s population is heavily concentrated in the west, and particularly the northwest, in and around Amman and a sizeable, but smaller population is located in the southwest along the shore of the Gulf of Aqaba. Ethnically, Arabs constitute 98 percent of the population, followed by Circassians and Armenians, at one percent each. Islam is the predominant and official religion, representing 97.2 percent of Jordanians (predominantly Sunni), followed by Christians at 2.2 percent (predominantly Greek Orthodox, but some Greek and Roman Catholics). Jordan’s economy is among the smallest in the Middle East, with limited supplies of water, oil, and other natural resources. Economic challenges for the government include: chronic high rates of poverty, unemployment, and underemployment. Literacy rates within the country are high at 95 percent (World Bank 2017; CIA 2017).

Jordan has sought to be a stable, moderating influence in the Middle East, but events inside the Middle East, including the Syrian conflict, the advance of Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL), ongoing conflict between Israel and Palestine, and the complicated management of Syrian and Palestinian migration flows threaten its borders and security. The repercussions have been significant: export routes to Syria and Iraq have been closed, rising insecurity has hampered tourism; and recent influxes of Palestinian, Syrian, and Iraqi refugees have strained the country’s already fragile resources and development efforts in both rural and urban areas (CIA 2017; Fanuli 2014).

Sixteen percent of the total population lives in rural areas, where poverty is more prevalent than in urban areas and living conditions are extremely difficult. As a chronically arid country with less than five percent of land available for farming and little to no rainfall, prospects of self-sustainability through farming are limited. Where farming does exist, farmers lack collateral and cannot obtain the loans needed for investment in farm activities that could lead to higher incomes. Further, they do not own land and are unwilling to make long-term investments on the land they cultivate as tenant farmers, and there is limited access to alternative sources of income. The most vulnerable groups include large rural households with low literacy and education levels, women-headed households, households with sick or elderly people, and households that do not own land or have very little land.

Jordan’s cities are home to 84 percent of the population and have the highest population growth rate in the Middle East, averaging near five percent annual growth. This growth is driven by increasing immigration from other countries (rather than mass movement of the rural population within Jordan), with Amman at the center of unregulated urban growth. Urban growth is based on spontaneous land-use planning decisions and partial initiatives, in addition to market and land speculation forces, leaving little choice but for infrastructure to follow. This unplanned development has led to increased pressure on limited green areas and water resources. If current trends continue, Jordan will be in absolute water shortage by 2025. Jordan is also host to about 1.4 million Syrians, including approximately 630,000 refugees as of 2017. While some 82 per cent of all refugees have settled in host communities, particularly in the urban area of Amman and the northern governorates of Jordan, the remaining 18 percent are hosted in refugee camps (IFAD 2015; Borgen Project 2017; UN Habitat 2017).

Though not a significant contributor to climate change, Jordan is one of the countries most affected by it and has begun to suffer from its negative effects, including increasing temperatures, increase in drought-affected areas, erratic rainfall, heat waves, and declines in available water (underground and surface). According to the 2013–2020 Jordan Climate Change Policy, the country is expected to experience a 15–60 percent decrease in precipitation and a 1 to 4 centigrade increase in temperature between 2011 and 2099, which will have serious impacts on natural ecosystems, river basins, watershed and biodiversity (GoJ 2013b; UN Habitat 2017).

Key Issues and Intervention Constraints

Both the government and international donors consider the water and environment sectors as the among the highest priority issues requiring interventions. The water situation in Jordan is complex and unsustainable: freshwater demands already exceed availability and surface and groundwater resources are polluted. At the same time, Jordan heavily relies on water resources outside its borders by sharing rivers and aquifers with neighboring countries. This leads to tensions, particularly with Israel and Syria. Additionally, Jordan has experienced large influxes of refugees as a result of the ongoing conflicts in the surrounding countries, which has increased Jordan’s struggle to meet domestic water needs. Recommendations from the Government of Jordan’s Water Strategy include: integrate water concerns into national development plans and sectoral strategies to ensure that strategically important but scarce water is prioritized and aligned to fulfill national objectives, especially as set forth in the National Water Strategy 2016–2025. At the same time, institutional capacity to roll out the water strategy and achieve its specific objectives is needed, including: developing innovative and efficient technologies, infrastructure, and partnerships to increase water productivity and water storage capacity; facilitating transboundary cooperation to maximize access to water supplies; developing and implementing a well-resourced climate change adaptation plan; and enhancing a targeted legal, regulatory, policy and institutional framework based on Integrated Water Resources Management (IWRM) principles (Al Dahdah et al. 2016; Schyns et al. 2015; GoJ 2016).

Jordan is currently facing significant challenges including the effects of climate change and land degradation (desertification), which affects productivity of rangelands, biodiversity, ecosystem services, and sustainable soil and water management. Forests play a pivotal role in Jordan’s efforts to mitigate environmental damage and in promoting its economy, since an estimated 20 percent of the population benefit directly from tourism to nature and forest reserves. The Government of Jordan asserts the role of public and private investment in realizing the objectives of The Jordanian National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan, National Action Programme to Combat Desertification, and other efforts to improve forest management. These may include implementing policy reforms and institutional strengthening of the forest sector. Reforms, for example, may include positive tax incentives and credits for the private sector, NGOs, and private citizens to reduce the loss of forests and to promote reforestation and afforestation projects (Westminster Foundation for Democracy 2016; GoJ 2006b; GoJ 2015c).

About 41 percent of Jordan’s total land area is characterized as degraded. The main factors are overgrazing, unsustainable agricultural and water management practices, and over-exploitation of vegetative cover. Dryland farmers and herders are increasingly adopting unsustainable land use practices to produce more food in order to meet their needs in the country’s rangelands. The present land tenure system, in which the State supersedes customary management by law but not in fact, also contributes to the destruction of natural vegetation in the steppe and desert rangelands. The Government of Jordan seeks to conserve, restore, and sustainably manage ecosystem services, as the basis for improved livelihoods. A key component of this process is to support an analysis of existing tenure and land rights, including common property resources and land and resource rights. The analysis should also include: a gender analysis of rights in order to understand how local stakeholders view their rights over land and natural resources and to identify ways in which different perspectives can be reconciled to enhance the country’s rangelands (Al Karadsheh et al. 2012; Kreshat 2006; Abu-Sharar 2006: BRP 2011).

The Syrian refugee population living in Jordan and Lebanon is young: 81 percent are under the age 35 and only a minority lives within refugee camps. As a result, Jordanian schools and hospitals are beyond capacity and competition for jobs has driven wages down, while prices for food, fuel, and rental accommodation have increased significantly for all. Syrian refugees are facing prolonged and often multiple displacements from housing, and fear of rising rental prices and competition to secure housing are two main areas of tension between refugees and host communities in Jordan. The Jordan Response Plan aims to foster the resilience of service delivery systems at national and local levels of Syrians on and off camps and expand employment and livelihood opportunities for Jordanians affected by the crisis. A key component of the Plan is also to stabilize and improve the tenure and housing situation by assisting with projects that: 1) upgrade sub-standard housing units in which Syrian refugees already live to adequate standards that meet international law; 2) increase the quantity of adequate housing that is available, affordable, and accessible to all on the rental market by working with property owners to upgrade existing properties that are currently not for rent; 3) provide conditional financial assistance to meet rental costs; 4) ensure security of tenure; and 5) enhance awareness on tenure rights and obligations amongst tenants as well as refugees who reside in non-camp settings (Verme et al. 2016; World Food Programme 2014; GoJ 2016).

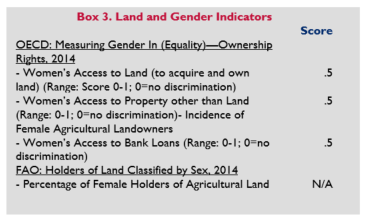

Women tend to use and manage land and other natural resources, while meeting water, food, and energy needs in households and communities, efficiently and sustainably. However, more efforts are needed to remediate restrictive social norms and implement measures, such as awareness campaigns, to promote joint-ownership of land for married couples and ensure women’s legal rights are realized. Implementation of new measures to protect women’s inheritance, both in terms of movable and immovable property, can also be implemented in combination with education and awareness campaigns relating to these new measures. Additionally, empowering women as leaders in the agricultural sector and climate smart agricultural techniques such as hydroponics, acquiring business skills and market connections, and ensuring access to credit can help to increase household food security and enhance economic participation in their communities (GoJ 2011; Nasarat et al. 2016).

Acute water scarcity and degradation of forests in Jordan have impacted food security, environmental conditions, and access to land for livelihoods. Water access and cooperation are also a source of regional tensions. Jordan has taken a lead in national policy reforms, especially in the water sector, to improve these key strategic assets. However, water resource development and management and access to freshwater is highly asymmetric between Jordan, Israel and the Palestinian territories and several of the water provisions in a 1994 Treaty between Israel to Jordan have not yet been implemented. Lack of political cooperation can impede technical solutions to existing water problems and can limit the effectiveness of water cooperation with regard to sustainable water management, as well as limit the impact of technical and civil-society initiatives. Future efforts in the water sector may include: Promoting regional water cooperation with the Government of Jordan and other national authorities in ways that consider the mutual benefits it offers for economic development, human security, and peace in the region; advocating for the empowerment and involvement of water users and stakeholder groups in the process of developing water policies and cooperative political frameworks; and transferring the successes of local and technical water cooperation initiatives regionally to the political level. In this way national and local water management institutions and practices can allow for involvement of stakeholder groups through systematic and “joined-up” processes (Souza 2014; Santos 2015; Al Karadsheh et al. 2012; FAO 2012).

Summary

Jordan is a relatively small, semi-arid, almost landlocked country with a population of over nine million. As an upper middle-income country with high literacy rates, Jordan is considered to be among the safest and most stable Arab countries in the Middle East, and has avoided long-term terrorism and instability. However, the events inside the Middle East, including the Syrian conflict, the advance of Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL), the conflict between Israel and Palestine, and the complicated management of Syrian and Palestinian migration flows threaten its borders and security.

Land use in Jordan may be characterized by limited arable land and shifting land uses, primarily in the form of urbanization leading to conversion of agricultural land, all driven by population growth and growing scarcity of water which is exacerbated by climate change. There are 93 municipalities plus the Greater Amman Municipality (GAM), which are home to more than 83 percent of the national population. Amman alone houses more than 50 percent of refugees.

Land use in Jordan may be characterized by limited arable land and shifting land uses, primarily in the form of urbanization leading to conversion of agricultural land, all driven by population growth and growing scarcity of water which is exacerbated by climate change. There are 93 municipalities plus the Greater Amman Municipality (GAM), which are home to more than 83 percent of the national population. Amman alone houses more than 50 percent of refugees.

There are three distinct agricultural regions in Jordan: the Rangelands, where grazing forms the basis for primary agricultural practice; the Highlands with rain-fed dependent field crops and forestry projects; and the Jordan Valley, with a high dependence on irrigation for farming.

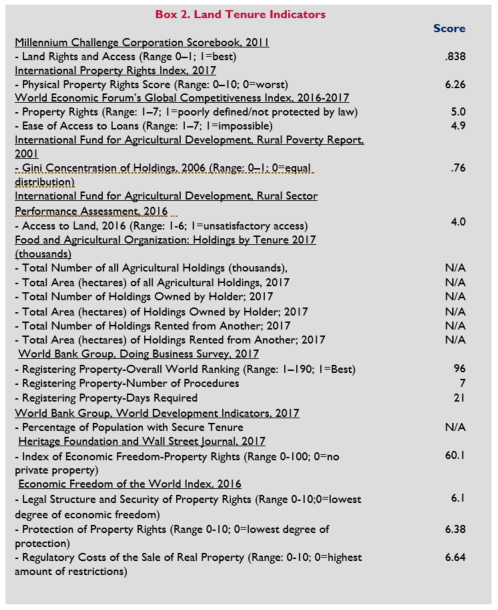

Jordan has a mixed legal system based upon civil law, Shari’a Law (Islamic Law), and customary law. The legal, institutional, and administration framework related to land reflects a gradual and deliberate movement toward land privatization and foreign nationals and investors have rights to buy land. De facto and de jure land law, particularly in its rangelands, have led to unsustainable land use practices and severe land degradation. Additionally, while both civil and Shari’a law provide women with relatively robust land rights, women’s de facto exclusion from property prevails due to extreme social pressure, intimidation, and even violence. Refugees and women-headed households are among the most tenure insecure, particularly as competition for scarce available land in urban areas is increasing.

Current land ownership in Jordan falls under three categories 1) Privately owned (Miri and Mulk) land that is registered and documented; 2) Tribal land (Wajehat El-Ashayeria), which had been historically distributed by Sheiks; and 3) State land (Al mawat), which provides free access to all resources to land owned by the State. Land tenure in Jordan, as in much of the region, reflects a gradual and deliberate withdrawal of the state from land ownership toward privatization. The basis for securing land rights in Jordan is land registration. While statistics claim that 95 percent of land is registered, this is only partially true. While private lands, representing more than 800,000 titles, are registered, State land, which accounts for 80 percent of the country’s total lands, are poorly defined and documented. Gender inequality is persistent in Jordan. Families headed by women tend to have fewer economic assets than households headed by men. For example, 43 percent of male heads of households receive loans for agricultural development and 14 percent for income-generating activities, while 21 and nine percent of female heads of households receive such loans. Women’s rights to land are enshrined within the Constitution, the legal framework, within Shari’a law, and even within customary law. The Department of Lands and Survey (DLS), established in 1927, is currently responsible for three main tasks: cadastral surveying, registration of land and property, and management of treasury (State) lands.

Land is one of the most valuable assets in Jordan. Jordan has a relatively large land area in comparison to its population. However, almost half the population lives in Amman. Competition for urban land has resulted in land prices that are amongst the highest in the region. Master planning initiatives have been undertaken in Amman, Zarqa and with particular success in Aqaba. Amman has released in its first city-wide Resilience Strategy. The Jordan Response Plan aims to foster the resilience of service delivery systems at national and local levels for Syrians on and off camps and expand employment and livelihood opportunities for Jordanians affected by the war in Syria the concomitant refugee crisis.

In terms of natural resources, Jordan has one of the lowest levels of water availability per capita in the world at 145 meters per year, far below the absolute poverty threshold of 500 meters per capita, per year. Water management in Jordan has focused on supplying additional water for human consumption. Many new policies and efficiency improvements have been undertaken to augment, conserve, reuse and recycle all available freshwater. While forest resources are limited, they provide important services, including contribution to soil conservation, watershed management, aesthetic and recreational value, biodiversity conservation and carbon fixing. The National Action Plan to Combat Desertification and National Agenda 21 includes mandates to support rangeland resources, address desertification, and improve forest resources. Climate change has and will continue to impact land use. Based upon trends of land use and cover change, population growth, the country’s water strategy and availability, and scenarios of current climate changes, irrigated areas will decline by 20 percent in the Highlands, rain-fed areas by 11–18 percent, and forests by 30–50 percent. Finally, the National Climate Change Policy of the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan 2013–2020 aims to build the adaptive capacity of communities and institutions in Jordan, including women and other vulnerable groups.

Land

LAND USE

Land use in Jordan is characterized by shifting land uses, primarily in the form of urbanization, leading to conversion of agricultural land, driven by population growth, growing scarcity of water, and exacerbated by climate change. Jordan has the highest population growth rate in the Middle East, averaging near five percent annual growth. Under current projections, between 2009 and 2030 the country’s population will double in size driven by increasing immigration, due mostly to conflicts in the Middle East, and to a lesser extent internal movement of young people from rural to urban areas in search of livelihoods. Refugees have also tended to aggregate into Jordan’s larger urban areas. At the same time, Jordan is comprised of arid and semi-arid regions and the country receives less than 200 mm of annual rainfall, which is variable, but upon which urban and rural residents depend for drinking water. Thus, as population size increases, so has the need for water and land to produce food, build houses, businesses, recreation areas, schools, health facilities, roads, and mosques, as well as other supporting uses (UN Habitat 2017; World Bank 2017c; Alqadi et al. 2013; Higher Population Council 2013).

As Jordan’s urban footprint is increasing, the land available for agriculture is declining. This is notable in a context where only 11.9 percent of the total land area can be considered agricultural land and less than three percent is arable. Less than 10 percent of agricultural land is irrigated and forests comprise a mere one percent of total land uses. With limited productive land and population growth manifest in urbanization, urban encroachment is increasing. Nationally, increased urbanization has been mirrored by declines in scarce fertile land from 383.86 km2 in 1918 to over 297.41 km2 in 2010. Vacant lands have declined from 232.42 km2 in 1918 to over 158.62 km2 in the same time period. The spatial growth of Amman alone has increased significantly from 0.32 km2 in 1918 to over 162.94 km2 in 2010. The area from Amman to Zarqa City, where more than half of the country’s population resides, has undergone intensive urbanization at the cost of rain fed and irrigated lands. It is estimated that 86 km2 of fertile land has been lost to urban development around Amman from 1918 to 2010, accounting for 23 percent of the total arable land in the Amman region. Shifting land use is also evident in the city of Irbid, where urbanization, desertification, deforestation, and change of land use from rain-fed cereal crops into open rangelands are present. A third notable shifting land use location is the Ajloun highlands, where forests have shifted into agricultural lands and land degradation has been accelerated by mismanagement of soils and crops. This uncontrolled deforestation has been the main cause of land degradation in the high rainfall zone in northwest of Jordan (Alqadi 2013; UN Habitat 2017; Al Bakri et al. 2013).

Climate change has and will continue to impact land use. Based on trends of land use and cover change, population growth, the country’s water strategy and availability, and scenarios of current climate changes, irrigated areas will decline by 20 percent in the Highlands, rain fed areas by 11 to 18 percent, and forests by 30–50 percent. These trends will be exacerbated if horizontal expansion of formal and informal cities, combined with vertical integration of surrounding cities, continues (Hamad 2017; Al Bakri et al. 2013).

LAND DISTRIBUTION

Jordan’s total land area is 89,342 (sq. km) of which 11.98 percent is agricultural land, 2.68 percent is arable land, 9.87 percent is irrigated, and 1.1 percent is forested. About 75 percent of the country has a desert climate and receives less than 200 mm of rain annually. The country is divided into three main geographic and climatic areas: the Jordan Valley, the Mountain Heights Plateau, and the eastern desert, or Badia region. The Jordan Valley, the country’s most fertile region, contains the Jordan River and extends from the northern border down to the Dead Sea. It is sparsely populated region with vast, uninhabited areas. The Mountain Heights Plateau region extends the entire length of the western part of the country, and hosts most of Jordan’s main population centers, including Amman, Zarqa, Irbid and Karak. The Badia region constitutes around 75 percent of Jordan’s total land area, is desert and desert steppe, and is part of the North Arab Desert, which stretches into Syria, Iraq and Saudi Arabia (GoJ 2017c).

There are three distinct agricultural regions in Jordan: The Rangelands, where grazing forms the basis for primary agricultural practice; the Highlands with rain-fed dependent field crops and forestry projects; and the Jordan Valley, with a high dependence on irrigation for farming. Historically, agriculture in Jordan had a seasonal focus and was highly dependent on the annual rain. Land holdings for crops have historically been small and self-sufficient, but there has been move away from small rural holdings to larger more intensive farming operations. This trend in agriculture has had an impact on the demographics within Jordan. Increasingly, rural youth migrate to urban centers as the agriculture sector no longer provides much employment. There are 93 municipalities plus the Greater Amman Municipality (GAM), which are home to more than 83 percent of the national population. Of the total non-Jordanian population, 1.26 million are Syrians, followed by 636,270 Egyptians and Palestinians, who do not have national ID numbers but who number 634,182. Nearly 50 percent of non-Jordanians reside in Amman (Ghazal 2016; OECD 2016; Health Population Council 2013).

LEGAL FRAMEWORK

Jordan has a mixed legal system based upon civil law, Shari’a Law (Islamic Law), and customary law. Civil laws relating to land are found in the Lands and Water Settlement Law and its Amendments (No. 40) of 1952; the Disposition of Immovable Property Law (No. 49) of 1953; the Management of State Property Law and its Amendments (No. 17) of 1974. The Lands and Water Settlement Law enabled development of “Settlement Areas” by the Department of Lands and Survey (DLS). The law was promulgated to establish settlements in the West Bank and requires all lands to be registered with the DLS. In Settlement Areas, transactions including selling, exchanging, emitting, and partitioning of land or water are considered null and void if such transactions are not registered with the Department of Lands and Survey. The Disposition of Immovable Property Law reinforces the role of the DLS and states that all transactions relating to public lands, dedicated lands, private lands, and the authority to issue official bonds (titles) relating to transactions must be confined to Lands Registration Departments, but can also be recognized by religious courts and authorities.

The Management of State Property Law and its Amendments, establishes mechanisms for State property delegation and lease for all purposes, including agricultural uses and housing. Shari’a law governs all matters relating to family law involving Muslims (or the children of a Muslim father), and Ottoman Family of Law, which has been superseded by Civil Law (No. 43) of 1976, provides the legal framework for inheritance. All citizens, including non-Muslims, are subject to Islamic legal provisions regarding inheritance. Finally, customary law can be found within pastoral customary property rights systems on Jordan’s rangelands, particularly grazing rights, and are associated with tribal institutions. Customary rights supported mobility across large areas of communally held land, with no one person having absolute rights to property. Customary law protected the resources within those lands and provided for their use in ways that promoted in rangeland conservation. Upon the elimination of these systems and rights and the declaration of rangelands as State-owned in the Agriculture Law (No. 20) of 1973, these customarily controlled areas that are now open for new and often unsustainable land uses, thereby eroding much of the “authority” of these customary governance systems. Customary law also addresses inheritance, which may differ from the rules of Islam (Ferr and Al Shoran 2008; Al Hariri 2014; GoJ 1952; GoJ 1953; GoJ 1974).

Urban land and planning related laws are found in the Villages Administration Law (No. 5) of 1954; the Municipalities Law (No. 29) of 1955, which introduced the concept of master planning for the first time; the City of Amman Planning Law, (No. 60) of 1965; the Town and Village Planning Law (No. 79) of 1966, and its various amendments. (GoJ 1954; GoJ 1955; GoJ 1965; GoJ 1966b; GoJ 1971; GoJ 2001b; GoJ 2007).

Protections for the environment are found in the Jordanian Environmental Protection Law (No. 52) of 2006, which describes prohibitions and penalties that inflict damage to the environment. Other laws that include environment-related legal provisions include: the Municipalities Law; the Cities, Villages and Buildings Organization Law (No. 79) of 1966; the Jordan Valley Development Law (No. 19) of 1968; Public Health Law (No. 21) of 1971; and the Agriculture Law of 1973 (GoJ 2006; GoJ 1996b; GoJ 1968; GoJ 1971; GoJ 1973).

The Leasing of Immovable Assets Law and The Sale to Non-Jordanian and Judicial Persons Law (No. 47) of 2006 govern foreign ownership of Jordanian residential and commercial properties. Foreigners may purchase residential property in urban areas subject to approval by the Minister of Finance or the General Director of the Survey Department, although citizens who are from Arab countries are exempted from this requirement. The term of ownership is quite restricted: it is limited to one 3-year period with an option to extend for a second 3-year period. Foreigners may inherit land and may also purchase commercial properties but are subject to restrictions described below (GoJ 2006).

TENURE TYPES

Tenure in Jordan, as in much of the region, reflects a gradual and deliberate withdrawal of the state from land ownership toward privatization. Current land ownership in Jordan falls under three categories 1) Privately owned (Miri and Mulk) land that is registered and documented; 2) Tribal land (Wajehat El-Ashayeria), which had been historically distributed by Sheiks; and 3) State land (Al mawat), which provides free access to all resources to land owned by the State. State land covers most uncultivated, so -called dead land (Al mawat, which means “nothing will survive in the area”) and which includes grazing lands operated under common property regimes. The Agricultural Law nullified Tribal Lands and gave the authority of managing the land to the Ministry of Agriculture. However, tribes continue to make de facto claims to these lands although they no longer divide and distribute lands among members (OECD 2013; World Bank 2012; National Center for Research and Development 2011).

In urban areas, privately owned land is transacted through sale or leaZse. However, urban informality is on the rise with at a growth rate of 4.3 percent per year. In some informal areas, such as Jabal Al-Natheef, the government has negotiated a hundred-year lease with the landowner to “host” informal developments. Authorization of State owned land for lease or purchase is only allowed for Jordanian nationals. However, foreign nationals and firms are permitted to own or lease property in Jordan for investment purposes and are allowed one residence for personal use, provided that their home country permits reciprocal property ownership rights for Jordanians (Abasa et al. 2012; Abed et al. 2015; Mazzawi 2013).

SECURING LANDED PROPERTY RIGHTS

The basis for securing land rights in Jordan is land registration. While statistics claim that 95 percent of land is registered, this is only partially true. While private lands, represented by more than 800,000 titles, are registered, State land, which accounts for 80 percent of the country’s total lands, are poorly defined and documented. Customary rights on these lands are unclear, leading to large-scale tenure insecurity. This is particularly exemplified in Jordan’s rangelands. Once characterized by effective land tenure systems and grazing rights associated with tribal institutions, these arrangements protected the resources within those lands and provided for their use in ways that assisted in rangeland conservation and continued productivity under the prevailing environmental and social conditions. Such resource governance systems have been formally eliminated and the lands declared as State-owned areas that are open for common use. Elimination of tribal ownership has led to lack of incentives to encourage Bedouins and other pastoralists to maintain and conserve the resources and rangelands. Informal sale of former tribal lands, both in rural and urban areas, still occurs. However, because all land transactions must be registered within the Department of Land and Survey to be considered valid, these transactions are not considered valid (even though a party or group may possess a customary title called a “hiija”). The DLS has tried to formally register the land in the names of those occupying them for a fee, but many have not paid the fee, leaving land unregistered (IBP 2012; Al Bakri et al. 2013; Al Dadah et al. 2016).

The basis for securing land rights in Jordan is land registration. While statistics claim that 95 percent of land is registered, this is only partially true. While private lands, represented by more than 800,000 titles, are registered, State land, which accounts for 80 percent of the country’s total lands, are poorly defined and documented. Customary rights on these lands are unclear, leading to large-scale tenure insecurity. This is particularly exemplified in Jordan’s rangelands. Once characterized by effective land tenure systems and grazing rights associated with tribal institutions, these arrangements protected the resources within those lands and provided for their use in ways that assisted in rangeland conservation and continued productivity under the prevailing environmental and social conditions. Such resource governance systems have been formally eliminated and the lands declared as State-owned areas that are open for common use. Elimination of tribal ownership has led to lack of incentives to encourage Bedouins and other pastoralists to maintain and conserve the resources and rangelands. Informal sale of former tribal lands, both in rural and urban areas, still occurs. However, because all land transactions must be registered within the Department of Land and Survey to be considered valid, these transactions are not considered valid (even though a party or group may possess a customary title called a “hiija”). The DLS has tried to formally register the land in the names of those occupying them for a fee, but many have not paid the fee, leaving land unregistered (IBP 2012; Al Bakri et al. 2013; Al Dadah et al. 2016).

Foreign nationals are afforded the right of ownership of property and land within urban borders in Jordan for residential purposes provided that the buyer’s country of residence maintains a reciprocal relationship. In order to purchase land, the foreign national must complete an application form filled out with information specifying the existence of a spouse and any minor children of the buyer and a site plan issued to the municipality. Prospective land and property buyers for commercial purposes must also obtain permission from the Minister of Finance or the General Director of the Survey Department. Once approval is granted, development must occur within 5 years. A failure to develop property renders any contract or ownership deed voidable. Nationals of Arab countries are exempt from this requirement (IBP 2012).

Refugees, particularly Syrian refugees, are the most tenure insecure in Jordan. Numbering 657,000 as of 2017, only 10 percent live in camps. Nearly 70 percent do not have security of tenure. A full quarter of refugee families are female-headed households and many households rent without basic rental agreements. This leaves families vulnerable to forced eviction and further displacement. Efforts to improve tenure security are evidenced in programs that provide rent-free accommodation to families most in need by upgrading sub-standard, uninhabitable buildings in the host community. Through negotiated bilateral agreements between prospective renters and land and property owners, renters agree to upgrade houses in exchange for the legal right to occupy the land and property for a 12–24-month period. Beneficiaries receive property through a signed lease that is registered with the local government municipality giving them legal protection against unlawful eviction (NRC 2014; Ghazal 2017; Goyes et al. 2017).

INTRA-HOUSEHOLD RIGHTS TO LAND AND GENDER DIFFERENCES

Gender inequality is persistent in Jordan. Families headed by women tend to have fewer economic assets than households headed by men. For example, 43 percent of male heads of households receive loans for agricultural development and 14 percent for income-generating activities, while 21 and nine percent of female heads of households receive such loans. Women’s rights to land are enshrined within the Constitution, the legal framework, within Shari’a law, and even within customary law. Article 7 of the Constitution stipulates that “Personal freedom shall be guaranteed,” while Article 6 asserts all “Jordanians shall be equal before the Law.” Land and property is covered under Jordanian Civil Law and the law treats men and women equally with respect to the capacity to own and handle property and conduct financial dealings using property. An adult female, like an adult male, has full legal rights to own, mortgage, and transact land and property buying, selling, leasing, giving power of attorney to others, mortgaging, and donating. She has the capacity to initiate financial contracts by herself or through others whether she is married or not. An adult woman is not required to have a male guardian over her property. The Provisional Jordanian Personal Status Law (No. 36) of 2010 stipulates in Article 320, “Each of the spouses shall have separate financial liability” and sets forth a number of provisions that protect the inheritance rights of women. These provisions specifically define heirs and their shares of land and property. A woman’s entitlement to inheritance varies in accordance with her legally defined “status” in relation with the decedent. Depending upon this status, women may be equal to men in inheritance, women may inherit more than males (relatives), women may be the sole inheritors, or women may inherit less land or property. Further, women have a guarantee of non-enforcement of any contracts obtained through coercion. Specifically, Article 142 of the same law provides special protection to women whose husbands force them to relinquish rights or property. Islamic Shari’a legal provisions apply to inheritance in Jordan and are reflected in Jordanian civil law as described above. Islamic Shari’a guarantees inheritance to males and females and stipulates that no one may deprive anyone of their right to inherit their shares. Moreover, heirs may not refuse their share of an inheritance, as is the case with wills and donations (Borgen Project 2017; GoJ 1952; GoJ 2010; Al Shafi’ee 2005; Jordanian National Commission for Women 2012).

Gender inequality is persistent in Jordan. Families headed by women tend to have fewer economic assets than households headed by men. For example, 43 percent of male heads of households receive loans for agricultural development and 14 percent for income-generating activities, while 21 and nine percent of female heads of households receive such loans. Women’s rights to land are enshrined within the Constitution, the legal framework, within Shari’a law, and even within customary law. Article 7 of the Constitution stipulates that “Personal freedom shall be guaranteed,” while Article 6 asserts all “Jordanians shall be equal before the Law.” Land and property is covered under Jordanian Civil Law and the law treats men and women equally with respect to the capacity to own and handle property and conduct financial dealings using property. An adult female, like an adult male, has full legal rights to own, mortgage, and transact land and property buying, selling, leasing, giving power of attorney to others, mortgaging, and donating. She has the capacity to initiate financial contracts by herself or through others whether she is married or not. An adult woman is not required to have a male guardian over her property. The Provisional Jordanian Personal Status Law (No. 36) of 2010 stipulates in Article 320, “Each of the spouses shall have separate financial liability” and sets forth a number of provisions that protect the inheritance rights of women. These provisions specifically define heirs and their shares of land and property. A woman’s entitlement to inheritance varies in accordance with her legally defined “status” in relation with the decedent. Depending upon this status, women may be equal to men in inheritance, women may inherit more than males (relatives), women may be the sole inheritors, or women may inherit less land or property. Further, women have a guarantee of non-enforcement of any contracts obtained through coercion. Specifically, Article 142 of the same law provides special protection to women whose husbands force them to relinquish rights or property. Islamic Shari’a legal provisions apply to inheritance in Jordan and are reflected in Jordanian civil law as described above. Islamic Shari’a guarantees inheritance to males and females and stipulates that no one may deprive anyone of their right to inherit their shares. Moreover, heirs may not refuse their share of an inheritance, as is the case with wills and donations (Borgen Project 2017; GoJ 1952; GoJ 2010; Al Shafi’ee 2005; Jordanian National Commission for Women 2012).

Despite these provisions, women’s de facto exclusion from property prevails. For example, a detailed study by the Jordanian National Forum for Women in the Governorate of Irbid found that 74 percent of women in the Irbid governorate do not enjoy their full inheritance rights and 15 percent of women of the same district voluntarily relinquished their rights to inheritance. Female heirs face pressures to relinquish their land and property rights. These may range from extreme forms of intimidation and even violence to more subtly coercive forms of taking land rights by way of male heirs who offer “gifts” to the female heir in exchange for her land and property shares. The social stigma that a woman may face if she contests violations in inheritance law is high and many will not use the court system to secure their rights. Some progress has been made, however, in improving the status of women in terms of land and property rights. Activists succeeded in working with the Shari’a Supreme Court to enable amendments to the Jordanian Personal Status Law. One of the most important of these amendments, Article 319, requires an estate attorney to inform all heirs of their inheritance. However, more recent analysis shows that legal improvements need to be accompanied by remedies to current obstacles to realization of women’s land rights which include: lack of women’s knowledge of their rights to inheritance; ignorance of the laws relating to the division of the inheritance; reticence to claim their right of inheritance; and the inability of women to claim their rights due to their weak economic empowerment. Remedies include awareness campaigns for women’s rights through religious institutions, civil society institutions, and organizing awareness campaigns through the media (GoJ 2011; Nasarat et al. 2016).

LAND ADMINISTRATION AND INSTITUTIONS

Land administration in Jordan has a deep history, with the establishment of the first institution dealing with land registration dating back to 1857 when the Ottoman government created Tapu, or land registry offices. The Department of Lands and Survey (DLS) was established in 1927 and is currently responsible for three main tasks: cadastral surveying, registration of land and property, and management of treasury (State) lands. A cadastral database has been established and the DLS has computerized all of its procedures and documents, including the land registers and cadastral plans. Land Registration Directorates and registration offices are located in all governorates and sub-governorates. DLS carries out several tasks concerning treasury (State) lands including leasing, expropriation, and control of subdivision and boundary fixing transactions done by licensed surveyors from the private sector. It also collects sales taxes and registration fees for the government. Even in special economic development areas, such as the Jordan Valley Authority and the Aqaba Special Economic Zone Authority, all land transactions must still be registered with the DLS (Madanat 2010; Jordan Valley Authority 2017).

Despite well-established land administration processes and institutions, some problems do remain. Most urban land is privatized while most non-urban land is State land. Private lands have become more expensive as demand increases while State lands, which are outside the land market, remain underutilized. Procedurally, land registration can be cumbersome: two witnesses must be present to sign for all land transactions; land and property information in the registry is accessible only by the owner, leading to a lack of transparency; and transaction costs are high for both individuals and commercial interests. Title transfer fees can amount to up to 10 percent of the sale price, although in recent years fees have been reduced to five percent in some cases (IBP 2012; Madanat 2010).

LAND MARKETS AND INVESTMENTS

Land is one of the most valuable assets in Jordan. In theory, Jordan has a relatively large land area in comparison to its population. However, almost half the population lives in Amman where competition for urban land has resulted in land prices that are amongst the highest in the region. Most urban land is privately owned, though this has occurred more through inheritance than through outright land purchase. During the land market “bubble” between 2005 and 2008, land speculation raised land prices by a factor of 10, due to scarcity of land to accommodate population influxes of Iraqi and Palestinian refugees, as well as higher land value assessments by the DLS. Although the land market stabilized in the intervening years, the influx of Syrian refugees since 2011, numbering as many as 1.5 million, has created high demand for rental housing. In districts in Amman, for example, prices of rented accommodation have increased by 200–300 percent versus pre-crisis levels. A 2015 survey indicates that 27 percent of Jordanians (more than 230,000 households) live in rented accommodation and 88 percent of them say that the cost of housing prevents them from finding a suitable home. Rental costs are highest in Irbid, East Amman and Madaba. Unfortunately, no official (or unofficial) indices of land and property exist within Jordan, making precise assessments of the status of the land market difficult (Oxford Business Group 2015; UN Habitat 2015).

Jordan has relatively little land inside urban areas and even less that has not yet been built upon. Most available land is in small, isolated pockets, often left over from other development or land allocated to Municipalities for the development and provision of social infrastructure and public purposes. As a result, large areas of undeveloped land are generally found only on the outskirts of settlements and are typically in the hands of private owners. In many cases, ownership of these lands is contested amongst families and subject to legal disputes. Thus, contiguous land parcels are the least available and most costly. Unfortunately, contiguous parcels outside of cities are also on lands that are most suitable for agriculture. A current trend for developers is to purchase, at a lower cost, isolated parcels and develop them despite the fact that these are not within the municipal boundary and therefore not eligible for infrastructure service provision. The hope is that in time, either the municipal boundary will expand to “cover” these developments, or that municipalities can be persuaded to extend services to them. At the same time, infill development to accommodate growth and ease pressure on the land and rental market is constrained by unwillingness of owners to sell land as land prices continue to rise, and a lack of zoning to encourage lower-income housing (Delmendo 2017; UN Habitat 2015).

COMPULSORY ACQUISITION OF PRIVATE PROPERTY RIGHTS BY GOVERNMENT

Article 11 of the Jordanian Constitution provides that “no property of any person or any part thereof may be expropriated except for purposes of public utility and in consideration of a just compensation, as may be prescribed by law.” Two other laws, the Investment Law (No. 30) of 2014 and the Land Acquisition Law (Decree No. 12) of 1987, provide for more detailed provisions on expropriation. Jordan is a signatory of many Bilateral Investment Treaties and recent legal developments have sought to encourage and protect economic activities. The Investment Law of 2014 addresses expropriation of an investor project (indirect expropriation) and allows for prompt and fair compensation in cases of expropriation. Specifically, “ownership of any economic activity may not be removed or be subjected to any procedures that would result in the same, unless it is expropriated for the public benefit, on the condition that fair compensation is to be paid to the investor, in a currency, which may be exchanged without delay.” The Land Acquisition Law deals only with land acquisition. Article 3 and Article 9 of the Land Acquisition Law states the two main conditions under which land can be expropriated: 1). No land can be taken away unless it is for public benefit and that there is fair and just compensation. 2.) The law requires direct negotiation between the purchasers or public benefit project and landowners until agreement is reached. In the event that agreement cannot be found between the two parties, cases are referred to the Primary Court that has jurisdiction in this area and to higher courts if necessary. Articles 11–26 state that the proper amount of compensation for land value is dependent upon: the amount of land confiscated; the purpose of confiscation; the percentage of land confiscated; and the status and size of the leftover land (OECD 2013; GoJ 2014; GoJ 2013).

The compulsory acquisition and expropriation law has been criticized for vagueness in what constitutes public benefit purposes and not clearly justifying the intended use for the land expropriated. Further, while the Land Acquisition Law allows for cash compensation to be paid for the expropriated land, it does not require development of alternative livelihood restoration strategies. Finally, there is no specific provision for tribal lands that are acquired or for the loss of traditional use rights (OECD 2015).

KEY LAND ISSUES AND GOVERNMENT INTERVENTIONS

Land degradation as a result of overgrazing, unsustainable agricultural and water management practices, over-exploitation of ground cover, and rapid population growth are key land issues for the Government of Jordan. The arid and semi-arid lands in Jordan are already affected by human actions and it is generally agreed the process of degradation of lands has been accelerated by unsupervised management and land use practices. Jordan has established a wide range of initiatives to address the problem of land degradation in the form of national legislation, strategies, programs, and research and monitoring. These include the 1992 National Environmental Strategy (NES), which established environmental planning and policy formulation in Jordan. Based on the NES, Jordan signed and ratified the UN Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD) in 1996. In 1995, the National Environmental Action Plan (NEAP) was prepared and remains the environmental guidebook for Jordan. In 2000, Jordan launched the multi-sectoral National Strategy for Sustainable Development or National Agenda 21. Other policies were developed between 1998 and 2006 to cover water, poverty, agriculture, biodiversity, socio-economic development planning, and desertification. Despite a well-established policy and legislative framework some key barriers and constraints hinder efforts to address land degradation. These include a lack of effective knowledge management, including collecting and disseminating data and information that can inform integrated land use planning; weak inter/intra-institutional coordination and insufficient and inadequate allocation of financial resources to realize legal and policy objectives (GoJ 2006b; GoJ 2007b; GoJ 2003; Karadsheh et al. 2012).

Jordan’s cities are home to approximately 83 percent of its citizenry, which on average are tripling in population every 25 to 30 years. This urban growth has been based primarily on spontaneous land-use planning decisions and partial initiatives without the benefit of coordinated land use and urban planning. The urban sprawl and lack of urban planning since the 1960’s has resulted in high costs to provide infrastructure and services. Even in areas where people build illegally, cities are forced to provide infrastructure. The government recognizes that planning for urban growth is critical as its young population matures and as demand for jobs, housing, transit and social services continues to increase. In response, a series of master planning initiatives have been undertaken in Amman, Zarqa and with particular success in Aqaba. Amman has released in its first city-wide Resilience Strategy. Further, the Ministry of Municipal Affairs is working to equip mayors and municipal councils with the tools to diversify its economies, create income-generating projects, and finance new facilities and infrastructure in their communities through Public-Private Partnerships. The Government recognizes the need to improve technical capacities for planning and management throughout Jordan’s cities, develop better data management systems, and remedy the disconnect between urban planning efforts pursued by municipalities and those organized and implemented by central government agencies (Center of Study of the Built Environment 2006; Hammad 2017; 100 Resilience Cities 2017; USAID 2017).

Women’s contribution to economic development, food security, the health and education of children and families, and asset management in Jordan is well documented. However, social restrictions on land inheritance and barriers to land ownership remain and have particularly adverse effects on poor women. The Jordanian Government, often in cooperation with NGOs, has worked to promote women’s empowerment, with some progress on removing legal barriers to land access, ownership, and use. These efforts started with major revisions to the Personal Status Law affecting women’s family and personal rights, such as introducing new grounds for divorce and improving services related to alimony and child support payments. Other notable reforms include expanding women’s control over economic assets—inheritance in particular; increasing women’s political participation through quotas in parliament and local councils; and addressing domestic violence. By law there are no longer legal restrictions on joint ownership of assets, including land and apartment units. A 2012 Jordan Demographic and Health Survey revealed that married women’s ownership of house and land titles increases with age and wealth. Urban married women and those from the non-Badia area or living in areas out of refugee camps are more likely to own a house than are rural married women. Women with higher education are also more likely to own either land or house titles. Despite the fact there are no legal restrictions on the ownership, purchase or sale of land and that women have equal rights in registering land both as individuals, and jointly through marriage, strong cultural, religious, traditional, and financial barriers will continue to impact women. Implementation of laws and regulations is often problematic in Jordan, especially when they conflict with social norms and further government interventions will be needed to address existing barriers (Sweidan 2015; Nasarat et al. 2016; GoJ 2010).

Climate change, water security, and food security are among the most critical concerns for Jordan. They are also interrelated, with water as the “face” of climate change. As incidences of drought have increased, this has had important implications for Jordan’s freshwater resources, which in turn affects the country’s largest water user, the agricultural sector. The government has established a policy framework climate change in the National Climate Change Policy of the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan 2013–2020. The long-term goal of the policy is to achieve a pro-active, climate and risk-resilient Jordan through a low carbon but growing economy; healthy, sustainable, resilient communities; sustainable water and agricultural resources; and thriving and productive ecosystems in the path towards sustainable development. At the same time, the Ministry of Agriculture is seeking to improve food security and reduce its reliance on food imports. The 2014 objectives of the Strategic Plan of the Agriculture Sector in Jordan are to enhance the ability of Jordanian farms to contribute to national competitiveness and food security. The Plan refers to climate change but does not establish an integrated framework to address both climate change and food security through agricultural development. It does call for increasing the efficiency of water use for irrigation and maximum output of yields per units of water. Finally, the Water Sector Strategy 2008–2020 (updated in 2012) has climate change as part of its vision. It focuses primarily on effective water demand management: effective water supply operations: institutional reform; recognizes the effects of climate change on water resources, and: seeks to integrate the management of water resources. It also calls for engagement with the private sector in the implementation of strategic projects. A gap in this otherwise solid policy framework is that it does not fully integrate land management into the above. That is, for example, land use plans and processes that will mitigate the continued encroachment of urban land onto agricultural land or encroachment of agricultural uses or unsustainable land use practices on grazing lands. Lack of land management and uses considerations lead to strains on water resources, reduction in agricultural activity, and land degradation, all of which can further exacerbate climate change (Rajsekharand and Goreki 2017; GoJ 2013b; EU 2014; Economic Policy Council 2017).

Food insecurity can be both a cause and consequence of conflict and there have been emerging reports of tensions between Jordanian and Syrian refugee populations, particularly in Mafraq Governorate, where poverty rates are high. Building the country’s adaptive capacity in the face of climate change and population growth to move towards land uses can enhance prospects food security. For example, donors can support initiatives that encourage better crop rotation and protect agricultural land in ways that also preserve farmers’ income levels, soil fertility, and water, which can be overlooked in the quest for more intensive farming. Land conversion is also a result of intense land speculation at the urban fringes due to lack of enforcement of zoning regulations, as well as zoning that supports uses for upper middle and upper income landowners and users. The result is large tracts of undeveloped, vacant urban lands. Municipalities and donors may collaborate to encourage urban agriculture infill development through, for example, such procedures as “down zoning,” which enables better access by the poor to urban land for housing to alleviate urban expansion. Through public consultations and analysis of existing zoning and land uses, zoning can better reflect actual needs and realities on the ground.

DONOR INTERVENTIONS

The EU and the Department of Lands and Survey Euro Twinning Project 2016–2018, also called the “Reducing discrepancies between the physical reality and the graphical cadastral information in Jordan” is being executed in cooperation with the governments of the Netherlands and Sweden and falls under the EU Technical Assistance Framework. The project is working to enhance the technical and administrative cadastral capacities of the DLS. It builds upon previous EU funded efforts beginning in 1996 and includes development of a secure and integrated cadastral system including Maps & Land registers (GoJ 2016c).

The World Bank’s “Piloting delivery of justice sector services to poor Jordanians and refugees in host communities programs 2016–2019” will provide, among others, legal services to address disputes related landlord-tenant relations and inheritance (including land). The program was conceived due to a marked increase in litigation as competition for access to public services and scarce resources that has fueled tensions and social conflict. The development objective is to increase access to legal aid services (information, counseling and legal representation) for poor Jordanians, particularly women, and refugees in host communities (World Bank 2016c).

UN-Habitat’s program focus for the period 2015–2017 is to work with central and local government partners to strengthen all aspects of governance and management in urban areas through: effective urbanization, urban planning, and local governance; improved land management and administration; increased emphasis on pro-poor housing; improved infrastructure and basic services; and strengthening resilience in urban protracted crisis. Ongoing projects include the Jordan Affordable Housing Project 2014–2018, which aims to will deliver houses to lower-middle income Jordanians without the use of subsidies, which can be occupied by the new owners or rented to low-income Jordanians or refugee households. Currently awaiting implementation, UN-HABITAT will be working with the Zarqa Municipality to provide technical support in preparing a Master Plan to accommodate city priorities and priority action plans (UN Habitat 2017).

The UNDP has worked extensively in the areas of climate change and the environment within Jordan with a mission to strengthen national capacity to support sustainable and climate resilient biodiversity conservation. The Mainstreaming Biodiversity Conservation in Tourism Sector Development Project in Jordan (2014–2017) aims to reduce the impact of tourism on biodiversity and to ensure that biodiversity conservation objectives are effectively mainstreamed and advanced into and through tourism sector development in Jordan. The project intervenes at three levels. At the national level, the project develops a regulatory and enforcement framework to reduce the impact of tourism on biodiversity. At the regional level, the project targets public awareness and sensitivity of the value of biodiversity. At the Protected Area site level, the project works to enhance capacity and management effectiveness of Protected Areas. The ongoing Global Environment Fund (GEF) Project seeks to provide technical support to the local community members, community-based organizations (CBOs) and civil society organizations (CSOs) in the GEF Focal Areas of Biodiversity, Climate Change Mitigation and Adaptation, Land Degradation and Sustainable Forest Management, International Waters, and Chemicals (UNDP 2017; UNDP 2017b).

Since 1981 IFAD has worked with the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan to support agricultural development and reduce rural poverty. IFAD has recently concluded the six-year “MENARID Mainstreaming sustainable land and water management practices project” in 2016. The goal of the project is to ameliorate land degradation, decrease water usage, and conserve biological diversity. Simultaneously, it strives to improve employment outcomes for people living in rural areas. Activities in the project included assisting the government in efforts to integrate sustainable land management and irrigation efficiency principles into community-driven natural resources planning; improving public awareness and capacity building on environmental issues; investing in conservation and sustainable land management practices that have proven to be successful; and supporting the monitoring of the environmental situation in the region. Its ongoing “Rural Economic Growth and Employment Project” (2014–2020) has the objective to reduce poverty, vulnerability and inequality in rural areas through creation of productive employment and income generating opportunities for the rural poor and vulnerable (in agriculture), especially youth and women (IFAD 2016; IFAD 2016b).

In 2015 the Department of Lands and Survey (DLS) entered into a public private partnership with Optimiza to improve DLS databases and their integration and enhance electronic services including: ownership permits for non-Jordanians; ownership permits for Jordanian nationals; permits to sell registered real estate to non-Jordanians; transferring transactions; issuing deeds, and improving the DLS’s website (Optimiza 2015).

Freshwater (Lakes, Rivers, Groundwater)

RESOURCE QUANTITY, QUALITY, USE AND DISTRIBUTION

Jordan has one of the lowest levels of water availability per capita in the world at 145 meters per year, far below the absolute poverty threshold of 500 meters per capita, per year. In addition to being one of the most arid countries, continual increasing demand for water has widened the gap between supply and demand. Water in Jordan currently comes from three main sources: surface water, groundwater (part of which is nonrenewable), and increasingly, treated wastewater. Jordan’s natural freshwater sources are rapidly deteriorating in quantity. The country’s major surface water resources are the Jordan River and the Yarmouk River, which is the largest tributary of the Jordan River. The Jordan River basin is shared by four sovereign states: Israel, Jordan, Syria and Lebanon and the Palestinian Territory. The lower part of the Jordan River originates in the Sea of Galilee and flows through the Jordan Valley into the Dead Sea and runs along the border between Jordan and Israel in the north, and the West Bank and Jordan in the south. Forty percent of Jordan’s water resources are shared, but water availability within these rivers has decreased significantly in the past 60 years due to diversions and intake by riparian countries. Jordan also consists of 15 surface water basins. According to its most recent statistic surface water availability comes from rainfall at 8884 million cubic meters (mcm), and groundwater at 485 mcm per year. However, the evaporation rate of rainfall per year is 8454 mcm, meaning that approximately 92 percent of rainfall is lost. There are 12 groundwater basins and an estimated 3000 wells in operation. Over-abstraction of groundwater for irrigation has reduced the water table by 5 m in some aquifers and tripled salinity (Ministry of Water and Irrigation 2016; Salman et al. 2016; Fanack 2017).

Agriculture is the largest water user in Jordan, accounting for approximately 60 percent of withdrawals. Despite representing only about three to four percent of Gross Domestic Product (GDP), agriculture is the main source of income for about 15 percent of the population, employs about six percent of the workforce, supports export-oriented value chains, and a large number in jobs in parts of the country where alternative job creation is difficult. Treated wastewater is becoming an increasingly important resource, with nearly 75 percent of this water used in the agricultural sector. Most of the treated wastewater is released from treatment plants near the major population centers (and major wastewater sources) into watercourses on the ridge of the Jordan Valley, where it flows into the valley for use in irrigation. The amount of wastewater has increased over the years, mainly due to the significant increase in population (including refugees). This has resulted in the existing wastewater treatment plants being used beyond their original design capacity, which has in turn caused the quality of treated wastewater to drop. As a result of this reduced quality, the treated wastewater cannot be fully exploited to progressively replace the freshwater resources for agricultural uses (Revolve Water 2017; GoJ 2015; Yorke 2013).

At the same time, water quality for all water sources is deteriorating. Untreated wastewater and agricultural fertilizer runoff continue to enter the Jordan River upstream from Israel, the West Bank, and within Jordan. In the Zarqa River industrial discharge, illegal dumping of sewage, illegal extraction of concentrated wastewater by farmers for use on crops, and the runoff of fertilizer from these farms has compromised water quality. As the result, the water from the Lower Jordan River and the Zarqa Rivers is no longer fit for human consumption. The quality of groundwater is also decreasing, mainly due to over-pumping, which often leads to increased salinity. About 70 percent of spring water is biologically contaminated and water resources have a significant level of toxicity (GoJ 2015; GoJ 2015b).

LEGAL FRAMEWORK

Three laws constitute the main legal framework of the water sector in Jordan: The Water Authority of Jordan (WAJ) Law (No. 18) of 1988, the Jordan Valley Authority (JVA) Law (No. 30) of 2001, and the Ministry of Water and Irrigation (MWI) Law (No.54) of 1992. These laws establish these institutional frameworks and regulate their activities. For example, the WAJ Law establishes and regulates the WAJ as an autonomous corporate body, with financial and administrative independence. By law, the WAJ has the mandate to: establish the required departments in all parts of the country in order to fulfill its obligations; purchase, acquire or lease properties, land and the related easement rights and the water rights required for the various WAJ projects; manufacture and produce commodities needed for its water and wastewater works; ensure technical control and supervision regarding the construction, operation and maintenance of all water projects and public or private sewers; obtain data and information regarding the needs of the country and consumption of water for different uses, and utilize such data for future planning; and provide for the country’s needs for water and to conserve its consumption The Jordan Valley Authority Law mandates the JVA to develop and protect water resources of the Valley for purposes of irrigated agriculture, domestic and municipal uses, industry, generating hydroelectric power and other uses. This is to be achieved through studies, planning, design, construction, operation and maintenance of irrigation projects; land reclamation; and overseeing public and private wells. The JVA is also entrusted with developing tourism in the Jordan Valley. Under the MWI Law, the Ministry of Water & Irrigation entitled to assume full responsibility for water and public sewage in the country; to develop and communicate water policy; assume full responsibility for the economic and social development of the Jordan Valley; and carry out all the works which are necessary for achieving these objectives (GoJ 1988; GoJ 2001; GoJ 1992).

Other legislation impacting water includes: The Temporary Public Health Law (No. 54) of 2002, which mandates the Ministry of Health (MOH), in coordination with the relevant authorities, to control and protect potable water, regardless of its source. MOH is entitled to control potable water resources and their networks, to ensure that these are not exposed to pollution. The Environment Protection Law for the year 2006 mandates the protection of the environment, including water resources (GoJ 2002b; GoJ 2006).

TENURE ISSUES

The WAJ Law stipulates that all water resources available within the boundaries of the country, whether they are surface or ground waters, regional waters, rivers or internal seas, are considered State owned property and shall not be used or transferred except in compliance with the Law. Private ownership of land does not include ownership of underground water as, under Article 3 of the law, groundwater is owned and controlled by the State. The Water Authority of Jordan (WAJ) is responsible for public water supply and issues permits to engineers and licensed professions to perform public water and sewerage works. WAJ receives application for drilling licenses and abstraction permits, and issues licenses and permits in accordance with the groundwater legislation. The WAJ supervises drilling, abstraction, and makes arrangements for the lease of land and use of groundwater for agricultural purposes in remote arid areas. It also issues licenses for well drilling rigs and drillers. Surface landowners may be granted a permit or license for extraction (wells) through the WAJ, which dictates the usage, amount of and any other conditions. That is, the license to extract water issued to the landowner is considered to be a permit to utilize it within the license conditions. Drilling licenses may not be granted to any person to drill a well on lands owned by the State. The Jordan Valley Authority (JVA), based on provisions of Jordan Valley Development Law, as amended, acquires land and water any other rights concerning lands and water for construction of irrigation projects and related structures such as roads and channels; lands acquisition to expand residential zone or agricultural projects; dam construction; and compensation to owners for any acquisitions for the above projects (Al Ansari et al. 2014; GoJ 2002; GoJ 2015).

Any water resources that are not under the management, responsibility, or supervision of the Water Authority of Jordan (WAJ) or the Jordan Valley Authority (JVA), which issue licenses, shall not be used in excess for personal or domestic needs. No persons or entities may sell water from any source or grant or transport it, without obtaining in advance the written approval from WAJ and within the conditions and restrictions decided or included in the contracts or agreements. Both the JVA and WAJ have sought to better control (and reduce) groundwater extraction by penalizing abuse of withdrawal levels dictated under licenses and closing illegal wells, which are prevalent. Allocation of water for domestic, industrial, tourism, educational, and agricultural use is based on a quota system, established by the JVA. Under current water policy directives allocating water is prioritized first to meet municipal requirements, followed by industrial needs and then agriculture. Thus, provisions for well licensing for agricultural purposes reflects where it stands in terms of priority and allocated quota. Although it may be a lower priority for ground and surface water, it is the first priority sector to receive treated wastewater (GoJ 2002; World Bank 2016b; WAJ 2017; GoJ 2015).

GOVERNMENT ADMINISTRATION AND INSTITUTIONS

A number of national and international players are involved in the Jordanian water sector, which results in a complex governance structure. Established in 1988, the Ministry of Water and Irrigation (MWI) is the main public water institution in Jordan. The ministry operates at policy-making level and is responsible for outlining the country’s water strategy, creating the national master plan for water use, preparing water studies, and monitoring water resources. There are three Secretary Generals within MWI, one for MWI itself, one for WAJ and another for JVA. They are required to answer to the Minister of Water and Irrigation. MWI contains eight directorates—Legal Affairs, Water Resources Development, Deep Wells and Drilling, Water Resources Planning, Environment, Public Information Affairs and Awareness, Financial, and the General Affairs and Project Directorate.

The WAJ operates under the MWI and is responsible for the operational management of water resources and the organization of water supply and wastewater treatment in the Highlands. It has been established as an autonomous corporate body, with financial and administrative independence. The WAJ has the mandate to: manage threatened groundwater resources through its control over groundwater pumping licenses; survey water resources, conserve them, and determine ways, means and priorities for their implementation and use, except for irrigation; implement approved water policies related to domestic and municipal waters and sanitation; develop water resources for domestic and municipal purposes, including digging of wells, development of springs, treatment and desalination of waters; execute works to augment the potential of water resources and to improve and protect its quality; issue permits to engineers and licensed professionals to perform public water and wastewater works; and regulate the uses of water, prevent its waste, and conserve its consumption.

The JVA also operates under the MWI. Under Article 3 of the Development of Jordan Valley Law (No. 19) of 1988, the JVA is obligated to create a plan for comprehensive development (farming, industrial, municipal, and tourist purposes) in the Jordan Valley area and to protect all water resources therein, as opposed to the highlands, and study, design, carry out, operate and repair irrigation projects. The JVA is also mandated to: undertake hydraulic and hydro-geological studies, and geological surveys; drilling of optional wells and establish monitoring stations; construct dams; settle water disputes; and develop appropriate tourism within the Jordan Valley (GoJ 1988; GoJ 2001; GoJ 1992).

It is important to note, that while the institutional structure of the water sector seems to be well-defined, the dynamics of the politics of water in Jordan are complex: There are multiple formal and informal, as well as regional, national, and international level institutions that play a role in the implementation of water policy. Further, the government has embarked on the establishment of water user associations (WUAs) to deliver retail irrigation services to farmers. Farmers in about 40 percent of the Jordan Valley are in various stages of establishing WUAs. Efforts to improve coordination across ministries and among donors can be seen in the existence of the National Water Advisory Council and the Highland Water Forum, which were created to coordinate water sector strategy and funding and to find collective solutions to, for example, groundwater management. However, more assistance is needed through institutions than can act as intermediaries that build linkages between currently disconnected actors, both formal and informal (GoJ 2015b; GoJ 2016; Sixt et al. 2017).

GOVERNMENT REFORMS, INTERVENTIONS AND INVESTMENTS