Overview

Jamaica is a lower-middle-income country with almost half its population living in rural areas and dependent on the land and increasingly depleted natural resources for livelihood. Agricultural land is unequally distributed. Most farmers can obtain only small plots through a tenure system based on kinship ties and have no written documentation of their rights to land. Insecure tenure has meant that productivity of these farms remains low; unsuitable farming techniques have contributed to soil loss and flooding.

Jamaica also has a large number of squatters (20% of the population) often occupying land that is environmentally fragile and unsuitable for occupation. Nineteen percent of the country’s population lives below the national poverty line. Two-thirds of Jamaica’s poor households are headed by women.

Water resources have been strained by population growth, pollution, and high levels of water use for domestic purposes. Deforestation has gradually worsened through decades of overexploitation and improper management.

Jamaica is a leading producer of alumina (aluminum oxide) and bauxite. The mining sector constitutes 60% of the country’s foreign investment. Unsustainable development of the sector has contributed to deforestation, soil degradation, and water pollution.

Key Issues and Opportunities for Intervention

USAID’s Country Assistance Strategy (2010–2014) recognizes the Government of Jamaica’s request for assistance targeting the agricultural sector. USAID has developed programs to promote rural economic development and food security through addressing unsustainable farming practices, the need for diversification of crops, and the development of markets. Complementary efforts to deepen programs could focus on the following:

The number of squatters and strength of family land tenure in the country suggest there may be value in exploring options for legal recognition of the various types of customary tenure, and strengthening appropriate customary systems and supporting institutions to complement formal titling programs. The government has been engaged in a multi-year project to title and register the country’s Land Administration and Management Program (LAMP). USAID is conducting an evaluation of the progress and impact of the program at this stage. The evaluation will determine how USAID might best assist in the improvement of land tenure security.

Donors could review existing governmental programs designed to address informal settlements on state and private land. USAID could also provide technical assistance to design a comprehensive strategy and accompanying legal framework, including the development of a plan for regularization of encroachment, and a system of incremental or stepped land rights, as appropriate. Donors could also assist in the design of dispute-resolution systems and appropriate tribunals for conflicts regarding urban and peri-urban land, including claims by squatters seeking redress for eviction.

Women tend to be among the poorest people in society. Although women can legally own land, in practice they rarely do. USAID’s Women in Development program has been engaged in Jamaica on issues of education and trafficking. This program could be extended to reach issues affecting women farmers in particular, including securing land rights and accessing credit and extension services.

As part of the agency’s commitment to helping the government increase security and reduce corruption, USAID could assist in building rural governance capacity at the community level as a fundamental part of interventions in natural resources management and enhanced rural livelihoods. Local governance mechanisms could be strengthened to address local environmental problems such as lack of compliance with environmental regulations.

Sustainable management of Jamaica’s watersheds, water resources and forest lands is a priority for the Government of Jamaica. USAID has been engaged in various community natural resources management programs, including the Ridge to Reef project. USAID could collect the experience of other projects and donors, develop best practices and lessons learned, and create models for community management of watersheds, water resources, and forestland.

Summary

Jamaica, the third-largest of the Caribbean islands, is a lower-middle-income country that is home to 2.6 million people and visited annually by another 3 million. Almost half of all households in Jamaica live in the island’s rural areas and depend on the land and the island’s increasingly depleted natural resources. Nineteen percent of the population lives below the national poverty line. Two-thirds of Jamaica’s poor households are headed by women.

Jamaica’s rural population suffers from insecure tenure and the unequal distribution of agricultural land. A small number of farmers control a disproportionate amount of farmland, monopolizing high-quality arable land and leaving small farms with marginal hillside land. The state owns and controls approximately 22% of Jamaica’s land, with the balance held in freehold, either individually or by families as family land. Thirty percent of private land in Jamaica is held as family land. This tenure system provides access to land based on kinship ties, but plots are small and characterized by low productivity. Few rural landholders have documentation of their rights to land. Jamaicans obtain access to land through inheritance, kinship ties, lease, purchase, and squatting. Although women in Jamaica have the legal right to own land and may be included on documents as joint or individual landowners, they are seldom landowners in fact, and are among the poorest members of Jamaican society.

The land market, particularly in sales and leases in urban areas, is robust. Yet because of the combination of economic hardship and housing shortages, approximately 20% of all residents are squatters, often occupying land that is environmentally fragile and unsuitable for occupation. Efforts to remove squatters often result in conflict, and government programs to provide services in some informal settlements have not kept pace with demand.

The land market, particularly in sales and leases in urban areas, is robust. Yet because of the combination of economic hardship and housing shortages, approximately 20% of all residents are squatters, often occupying land that is environmentally fragile and unsuitable for occupation. Efforts to remove squatters often result in conflict, and government programs to provide services in some informal settlements have not kept pace with demand.

Formal laws governing land in Jamaica are limited in number and scope, and efforts to improve land- administration institutions and processes are ongoing. Jamaica’s 1996 Land Policy aims to promote development and sustainable use and management of resources. The policy covers a wide range of topics, including land administration, conservation, and the institutional framework for land administration.

Increasing population growth, pollution, and high levels of water use for domestic purposes have strained water resources. Declining water resources most dramatically impact impoverished communities which, in turn, rely more heavily on natural resources such as forest land and products. Unsuitable farming techniques have contributed to massive soil loss and flooding. Deforestation has gradually worsened through decades of overexploitation and improper management.

Jamaica is a leading producer of alumina (aluminum oxide) and bauxite. The mining sector constitutes 60% of the country’s foreign investment. Unsustainable development of the sector has contributed to deforestation, soil degradation, and water pollution.

Land

LAND USE

Jamaica is the third-largest of the Caribbean islands, with a total land area of 10,800 square kilometers. Forty- seven percent of the country’s land is agricultural (5120 square kilometers). Approximately 10% of the total land mass is permanent cropland (World Bank 2009).

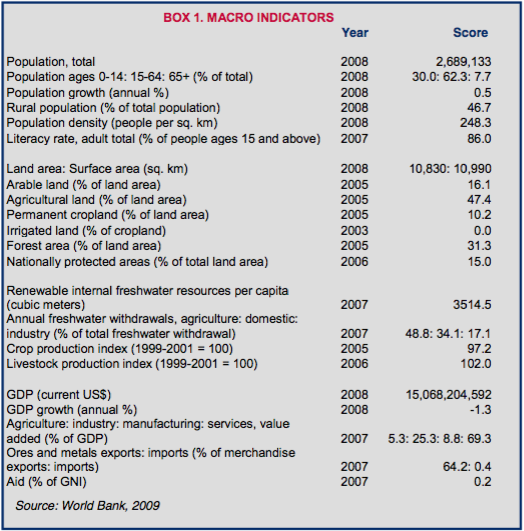

Jamaica had an estimated total population of 2.6 million people in 2008. Forty-seven percent of the population is rural. As of 2003, 19% of the total population lived below the national poverty line. The percentage of rural families living in poverty is twice the rate of poverty in Kingston. Female-headed households account for two-thirds of all poor households (CIDA 2009; UN 2009; World Bank 2009; World Bank 2005).

Jamaica is a lower-middle-income country and has experienced modest long-term growth. Jamaica’s 2008 GDP was US $15.1 billion. In 2007, 5% of GDP was attributed to agriculture, 25% to industry, and 69% to services. Women make up 30% of the agricultural labor force (CIDA 2009; USAID 2009a; JSDN 2005; World Bank 2009).

Eighty percent of Jamaica’s land surface is mountainous or hilly. The highest area in the country is the Blue Mountains. Thirty-one percent (3380 square kilometers) of all land is forested. The country is also characterized by plateaus, notably the John Crow Mountains and the Dry Harbour Mountains. Nationally protected areas make up 15% of the land area (USACE 2001; USAID 2006; World Bank 2009).

Eighty percent of Jamaica’s land surface is mountainous or hilly. The highest area in the country is the Blue Mountains. Thirty-one percent (3380 square kilometers) of all land is forested. The country is also characterized by plateaus, notably the John Crow Mountains and the Dry Harbour Mountains. Nationally protected areas make up 15% of the land area (USACE 2001; USAID 2006; World Bank 2009).

The country’s land and natural resources have been used indiscriminately and are degraded. Poor land-use practices, including cultivation and development on unsuitable slopes, have led to soil erosion and degradation of watersheds. The annual rate of deforestation is 0.1%. The proliferation of squatter settlements in fragile areas also contributes to environmental degradation, as has tourism-based development (daCosta 2002; daCosta 2003; World Bank 2000; World Bank 2002; World Bank 2009).

LAND DISTRIBUTION

Jamaica has a long history of unequal agricultural land distribution. Jamaica’s agricultural land remains concentrated among a small number of large farms, though landholdings have become slightly less concentrated over the past decades. In the 1970s, less than 1% of farms occupied approximately 57% of cultivable acreage, while 81% of farms (under 2.5 hectares each) occupied approximately 16% of the land. While more recent data on land distribution is not available, government divestment programs over the past three decades have moderately increased the amount of land controlled by small farmers and landless households. Still, large farms control the vast majority of high-quality agricultural lands along the coasts, while small farms are generally located on marginal hilly land, and holdings are frequently divided among two to four small plots. The Land Utilization Act (see Legal Framework, below) helped pave a legal pathway for expropriation of idle lands from large farms, although the extent to which it was used is not clear. Project Land Lease is an example of a program which sought to redistribute idle land for small farmers, providing them with land, technical advice, inputs such as fertilizer, and access to credit, allowing the government to encourage the productive use, sale, or lease of rural land (JSDN 2005; Meikle 2009; daCosta 2003; Gentzkow 1998).

In urban areas, land is divided between formal and informal holdings. Lack of access to affordable land in the formal sector drives the steady growth of the informal housing sector, which captures approximately 57% of all new housing construction. In a recent study, the Jamaican Ministry of Water and Housing identified 754 squatter settlements in the country, representing a 19% increase over a six-year period. These settlements housed 20% of the population, and are generally characterized by shack-like dwellings, overcrowding, lack of basic services such as water, improved sanitation and electricity, substandard health, elevated crime, and high levels of environmental degradation (daCosta 2003; Cummings 2009).

LEGAL FRAMEWORK

The formal laws governing land in Jamaica are numerous; however, several pieces of legislation are critical to land and land use.

The Jamaican Constitution provides that the right to use and receive income from property is a fundamental right (GOJ 1964).

Registered land in Jamaica is governed by the 1889 Registration of Titles Act and the 1969 Registration (Strata Titles) Act. The Registration Act was enacted to facilitate the subdivision of land into strata, or what are commonly known as apartments. Although the 1889 Registration of Titles Act is substantially the same as it was at its inception, a 1968 amendment has had a significant impact on the scope of land ownership in Jamaica. Sections 85–87 of the Act allow persons to acquire a good title against the registered proprietor by possession; squatters are thus allowed to apply for a registered title after a period of time if they are in possession of privately owned land (Allen 1993; GOJ 1964; Reynolds and Flores 2009; GOJ 2006b).

The 1966 Land Development and Utilization Act defines the criteria to be used on the designation of agricultural land – as well as the responsibilities of the occupier and the rules for dispossession – and establishes the Land Development and Utilization Commission (GOJ 1966).

Over the past few decades, the Jamaican Government (GOJ) has embarked on a number of legislative initiatives geared toward the proper management, conservation and protection of natural resources within the context of sustainable development. Many of these initiatives are sector-based; they include: the 1991 Natural Resources Conservation Authority Act; the 2000 Endangered Species (Conservation and Regulation of Trade) Act; the 1992 Natural Resources (Marine Parks) Regulations; the 1995 Forest Act; and the 2001 National Solid Waste Management Act (GOJ 2003a).

TENURE TYPES

Land tenure in Jamaica can be classified into legal, extralegal, and customary. The primary legal tenure forms consist of freehold tenure and leasehold.

Freehold. Freehold land is property held in absolute possession. Most freehold land was originally low-lying land suitable for sugar plantations. In the 1980s, government policies toward land tenure shifted in favor of the privatization, commercialization, and modernization of agriculture. Sugar cooperatives were dismantled and government holdings were divested. Subsequently, smallholders gained freehold land through grants from landholders, donations, or programs organized by the government.

Leases. Individuals and entities can also lease land for agricultural, residential, industrial, commercial and recreational uses. Lease terms vary in length, but the maximum period for a lease of state land is 49 years. Both private and state land may be leased in Jamaica by individuals and entities (Olwig 1997; Gentzkow 1998; daCosta 2003).

Customary tenure. Approximately 30% of land in Jamaica is held in family lands, a form of freehold tenure where rights are jointly shared among an entire kinship group. Traditionally, three rules governed family lands: (1) all offspring, regardless of gender, birth order or legitimacy, share inherited lands equally; (2) absentee owners do not forfeit their rights, but rather perennially reserve the right to return and claim their share of the plot; and (3) family lands may not be sold or permanently subdivided. In reality today, the rules governing family land are more fluid: a family plot is generally shared among siblings or first cousins, and is managed and used only by those who remain to farm, not shared in any meaningful way with those who have left the area. The farming household on family land often appears, for all intents and purposes, to be its full owner; it is usual for this household to work the land exclusively, harvesting the crops, and build its house on the land. Nonetheless, many continue to believe that family land is only temporarily divided and that all rights-holders retain rights to the entire land area (daCosta 2003; Stanfield et al. 2003; Gentzkow 1998; BizClir 2008).

Extralegal tenure. The main extralegal means of tenure is squatting. Jamaica has a long history of squatting, dating as far back as the emancipation period in the nineteenth century. Following the abolition of slavery in 1834, landless former slaves acquired illegal holdings, not only from vacant Crown land but also from land abandoned by planters due to a shortage of farm labor. The squatted land was used both for building homes and for subsistence agriculture. An estimated 20% of the population lives in squatter settlements, and 82% percent of squatter settlements are in urban areas. Seventy-five percent of squatters occupy government-owned land (vs. non-government land). These lands are also referred to as captured lands. Squatting has become an institutionalized form of tenure, and squatters may acquire possessory rights to private land after 12 years and rights to state land after 60 years, although the rate of formalization of squatter rights is unknown (da Costa 2003; Tindigarukayo 2004; Stanfield et al. 2003; Cummings 2009).

In some cases, large extents of land are held in common by a community. Common lands are often the result of collapsed plantation systems and include commonly held treaty land held by a group known as Maroons, who are descendents of escaped slaves (Stanfield et al. 2003).

SECURING LAND RIGHTS

Jamaicans obtain rights to land through inheritance, purchase, lease, kinship ties and squatting.

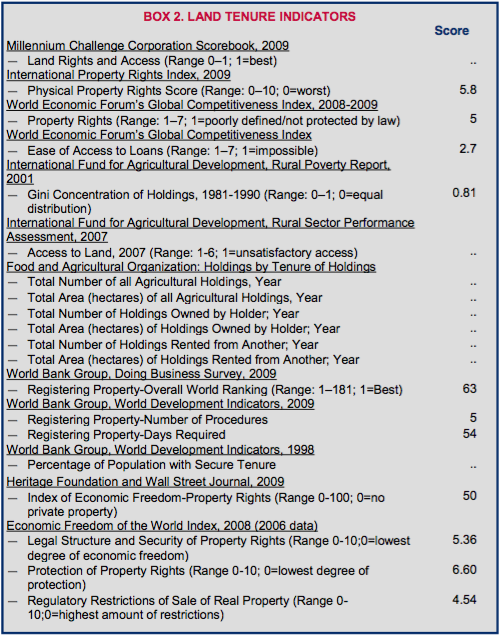

The purchase of land requires a prospective landowner to conduct a land survey, and conduct a title search to establish whether conflicting interests exist or if other claims against the property have been registered. There are two kinds of land titles in Jamaica: common law titles and registered titles. A common law title is a certificate of ownership used for unregistered land; although a common law title is not a full title to the land, it can be upgraded to a registered title. The registration process for a registered title is undertaken in five steps. Claimants must: (1) conduct a title search at the National Land Agency; (2) obtain a certificate of good standing from the Registrar of Companies; (3) have taxes and duties assessed of tax at the National Tax Authority; (4) pay tax and duties at the National Tax authority (at which point the transfer deed is sent for cross-stamping); and (5) apply for registration at the National Land Agency. This registered title is both legal and official. The Registration of Titles Act stipulates that the original must be retained at the Office of Land and Titles. Of the approximately 650,000 land parcels in Jamaica, an estimated 45% are documented with registered title (World Bank 2008; GPG 2007a; Gentzkow 1998; Stanfield et al. 2003).

Approximately 21% of the population lives on rented/leased land, a percentage that has been declining steadily since 1997 (27%). This decline been cautiously interpreted as an outcome of consistent efforts to regularize ownership and land tenure (Nadelman 2009).

Most Jamaican farmers occupy their land without any formal documentation of their rights. In most cases, local communities recognize these rights even though they have not been formalized under registration laws (Gentzkow 1998; Stanfield et al. 2003).

Rights to family land are informal, and many of the rights-holders are likely to be working in the city or abroad. Generally, those who remain divide the land among themselves. Because family land is jointly owned (with rights vested in the immediate kinship group), the land is difficult to register, which can be a problem for households seeking to finance home construction, including those applying for government housing programs that require proof of land ownership. Multiple persons are entitled to make a claim to the land, even if they are living abroad.

At times, there are so many claimants to the land that no identifiable group can be declared the owner. In such situations, the matriarch or patriarch of the family oversees the informal individualization of plots for residential and farming use. The degree of tenure security on family lands is debated among scholars, and varies according to regional and family norms. Some observers note high levels of tenure security, as division and redrawing of boundaries is a frequent source of conflict, and farmers must operate with the constant possibility that an absentee owner will return to claim his or her portion of the land (Gentzkow 1998; Stanfield et al. 2003).

Rural-urban migration, housing shortages, economic hardship, the high cost of land, and the availability of idle land often lead people to move onto private and public lands. Many individuals illegally utilize reserved or environmentally fragile spaces. Squatters often occupy plots either that are not viable for development, or whose ownership is disputed. In the latter situation, squatting creates tenure insecurity for both the landowner and the squatter. However, as described in the discussions on tenure and the legal framework above, according to the 1968 amendment to Registration of Titles Act and the Jamaican Statute of Limitations, possessory rights can be secured on private land after 12 years of peaceful, undisturbed possession. Possessory rights can also be acquired in respect to government-owned land, but only after 60 years (daCosta 2003; Tindigarukayo 2004; Stanfield et al. 2003; Cummings 2009).

INTRA-HOUSEHOLD RIGHTS TO LAND AND GENDER DIFFERENCES

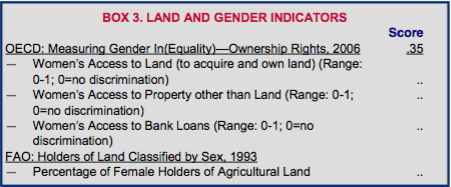

Jamaica scores high on gender indicators yet women tend to be among the poorest members of society. Women are primarily employed in the insecure informal sector or in low-paying jobs in the formal sector. Women are poorly represented in the political sphere, and women policy-makers are limited in number (Wyss and White 2004).

Jamaica scores high on gender indicators yet women tend to be among the poorest members of society. Women are primarily employed in the insecure informal sector or in low-paying jobs in the formal sector. Women are poorly represented in the political sphere, and women policy-makers are limited in number (Wyss and White 2004).

Women in Jamaica have strong legal rights to land. They can legally own land and be included on documents as joint or individual landowners. A married woman can own and register a property title under her name alone. Under customary law, daughters and sons are equally entitled to inherit family land. Despite these provisions, few women own land legally in Jamaica. Women most often access land through their spouse, partner, or family; they may also rent land. Although women operate 19% of all farms, they receive only 5% of the loans granted by the Agricultural Credit Bank (Ellis 2003; Crichlow 1994; FAO n.d.).

Jamaican law provides a surviving wife with the right to inheritance in regard to family homes and other marital properties. Under the 2004 Property (Rights of Spouses) Act, even where the family home is registered in one spouse’s name alone, any transaction concerning the family home nonetheless requires the consent of both parties. Though neutral in its provisions, practical application of the law benefits women, as deficiencies in the old law (which placed women at a disadvantage in proving entitlement to property) have been removed. The Act has also been extended to include a single woman who has cohabited with a single man for a period of not less than five years, or vice versa. Commentary on the law’s de facto application is not available at this time (GPG 2007b; Bailey 2002; Jamaica Gleaner 2008).

LAND ADMINISTRATION AND INSTITUTIONS

There are two different types of land registration systems in Jamaica: the Deed recording system and the Torrens title registry system. Land parcels registered with a Deed are recorded at the Island Records office in Spanish Town. The Island Records office is used to record deeds of sale and transfer of real property between parties. Deeds have legal recognition; however, most banks are unwilling to use a Deed as a source of collateral due to poor record keeping, the absence of checks and approvals, and the failure of linking a Deed to a cadastral index map.

Under the Torrens system, a title is recorded in the Title registry which is now housed within the National Land Agency. In 2000, the National Land Agency was established with the objective of streamlining the administration and management of land (government-owned lands in particular). The National Land Agency is responsible for the creation of a land-titling system, modern cadastral maps, and land-information systems. The National Land Agency is made up of seven divisions: (1) land titles; (2) surveys and mapping; (3) land valuation; (4) estate management; (5) business development and technology; (6) corporate services; and (7) corporate legal services. The Commissioner of Lands is the CEO of the National Land Agency and reports to the office of the Prime Minister (GOJ 2006b; daCosta 2003).

The National Environment and Planning Agency (NEPA) is responsible for the efficient and sustainable use of land and natural resources. The agency’s core functions include policy and program development, sustainable development planning, environmental and natural resource mapping and database-maintenance, habitat protection, biodiversity conservation, watershed and pollution management operations, and public education (Stanfield et al. 2003; daCosta 2003; GOJ 2003a; GOJ 2006a).

LAND MARKETS AND INVESTMENTS

In Jamaica, property prices throughout the country have largely remained static for the last two years, high transaction costs, perceptions that the registration process is lengthy, and inconsistencies in titling practices have potentially inhibited the growth of the land market.

The cost of transferring land in Jamaica is among the highest in the world, ranking 108th of 178 countries studied by the World Bank. Land transactions include fees, charges and commissions, and can amount to more than 20% of the cost of the transaction. In addition to fees, taxes (including a transfer tax and stamp duty tax) represent obstacles to the development of an active and free commercial or residential real estate market in Jamaica. For example, stamp duty must be paid within 30 days after the date of an agreement to sell the land is entered into – even though the sale itself may never take place, or takes place much later, as is common. If the sale does not take place, the tax can only be recovered from the government through a cumbersome refund process. In addition, these taxes apply whether the land being transferred is titled or untitled, and they apply to gift transfers between family members, and transfers by inheritance upon death. As a result, prices are purposely held down, constraining the land market (BizClir 2008; World Bank 2008; IDB 2006).

The rural land market is particularly affected by the above factors. For people in rural areas, the process of titling and registration may be so costly as to make it prohibitive. As a result, weak land rights are hindering the development of the private sector in rural areas, and among smaller businesses. In addition, the prevalence of family land has inhibited the rural land market. Because this land is handed down within families, generation to generation, without formality as to title or formal means to recognize the separate parts held by individual family members, land sales are very difficult to execute. Even where land is held individually, a considerable number of people lack knowledge of how to purchase and sell land (Dunkley 2010; BizClir 2008; IDB 2006; GOJ 2010).

The urban land market is distorted as a result of rapid urban growth combined with availability of idle land owned either by the government or by absentee landlords, which has led to squatting. Because economic growth over the past decade has been unaccompanied by an equal growth in the provision of housing facilities, prices for houses and/or rents have increased. In the absence of affordable accommodation, poor and landless arrivals to urban areas resort to squatting (daCosta 2003; GPG 2009).

Jamaica’s housing market has been weak for the last two years due to poor economic growth, high inflation and the global economic downturn, which has negatively affected overseas investment in all sectors. The Jamaica property market is attractive to investors from other countries. Foreign land buyers, both individual and corporate, are further favored in the real estate market, as the transfer tax on land transaction applies only to local individuals or companies. The rental market was stable in 2008 with rental yields over 12%. Because of very limited supply, locals and expatriates compete for the few rental properties available in the market (BizClir 2008; GPG 2009).

COMPULSORY ACQUISITION OF PRIVATE PROPERTY RIGHTS BY GOVERNMENT

Under the Constitution, land can only be taken according to the procedures laid out in law, with compensation paid, and a right of appeal to the court system (GOJ 1964; World Bank 2006a).

The 1947 Land Acquisition Act vests authority in the Commissioner of Lands to acquire all land required by the Government for public purposes. Public purpose is not defined. The Commissioner is empowered to acquire land either by way of negotiation or compulsory acquisition. Rights of appeal relate only to the level of compensation (World Bank 2006a).

The simplified land-acquisition procedure includes the following steps: (1) ensuring publication of a notification in the Gazette, with a copy served to the owner; (2) carrying out a land survey; (3) initiating negotiation with property owners; (4) if no agreement is reached, the Commissioner posts notices at the land that claims to compensation may be made to him at a specified time at least 21 days after the posting of notices; (5) the Commissioner determines the specific area to be acquired, the compensation amount, and apportionment among multiple owners; and (6) if any dispute arises as to the compensation, the Commissioner may refer such dispute for the decision of the Court (World Bank 2006a).

In determining the amount of compensation, the following is taken into consideration: (1) market value at the date of the service of notice; (2) damage, if any, caused by the acquisition; and (3) reasonable expenses, if any, related to the change of residence or place of business (World Bank 2006a).

LAND DISPUTES AND CONFLICTS

Squatting is a widespread problem in Jamaica and results in disputes between squatters and the local government, squatters and landowners, and squatters with one another. In recent years some disputes have instigated protests and isolated incidents of armed resistance by squatters. In 2007, a fifteen-year dispute between squatters and a landowner culminated in protests when the landowner offered to relocate the squatters. The squatters were concerned about their lack of security in the proposed location. In 2006, a private developer was met with armed resistance when he attempted to move squatters off his land (Gentzkow 1998; Jamaica Gleaner 2007; Blair 2006).

Although disputes on family land are rare, they can arise over boundaries and allocation of specific portions, such as when one co-owner attempts to build a house on a small plot of land (Gentzkow 1998; Stanfield et al. 2003; Shearer et al. 1991).

The GOJ’s efforts to expand land-access by selling or leasing out government-owned land, i.e. land divestment, are causing a series of disputes on issues of land valuation and procedural transparency (Jamaica Gleaner 2000; Jamaica Observer 2005).

KEY LAND ISSUES AND GOVERNMENT INTERVENTIONS

The goals of Jamaica’s 1996 Land Policy are to promote development and sustainable use and management of resources. The policy covers a wide range of topics, including land administration, conservation, and the institutional framework for land. Jamaica’s National Planning Summit 2007 identified land titling as one of the country’s seven priority needs. Specific objectives included creating within two years an inventory of all lands, and registering 90% of all land within 10 years (Stanfield et al. 2003; BizClir 2008).

During the 1990s and early 2000s, the government undertook several land titling projects for the purpose of establishing a land management system that would secure tenure in rural and urban areas. In 2001, the Land Administration and Management Programme (LAMP), a pilot project jointly funded by the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) and the Government of Jamaica, was established. The project has been designed to implement a number of the recommendations contained in the National Land Policy and has four components: Land Registration; Land Information Management; Land Use Planning and Development; and Public Land Management (IDB 2006).

The objectives of the Land Registration component are to create a cadastre and to clarify and regularize the tenure of 30,000 parcels of targeted land. The cadastre was created, but landholders initially resisted formalization due to the costs and complications of land transactions and title registration, and a general objection to the idea of formalizing and recording land ownership. Landholders’ concerns, coupled with the government’s uncertain coordination of the project, resulted in the project initially titling less than 1000 parcels. In an effort to make the service more affordable to all landowners in the pilot area, fees associated with the process (such as for surveying and transfer) have been reduced, and stamp duties waived. Improvements to the pilot project led to more than 3000 parcels of land being registered and titles updated since 2000. In 2008 LAMP was extended for an additional five years. As of May 2010, of 800,000 private land parcels in all fourteen parishes of the country, approximately 350,000 were unregistered and another 100,000, even if registered, were not updated on the register (daCosta 2002; daCosta 2003; BizClir 2008; GOJ 2008a; Jamaica Observer 2010).

As the largest owner of land in the country, the GOJ has committed to transferring portions of its landholdings into private hands through an acquisition and divestment policy. A focus of this program is to provide land for low-income earners and for squatter-settlement upgrades. A land divestment manual is being prepared to govern this process. The GOJ has programs to upgrade and regularize squatter settlements and create a shelter program (daCosta 2003; World Bank 2002).

The GOJ announced the Program for Resettlement and Integrated Development Enterprise (Operation PRIDE) in 1995. Operation PRIDE was established to solve the above problems by attempting to attain four related objectives: (1) resolution of shelter needs of low-income Jamaicans through the establishment of new planned settlements, the regularization of illegal settlements, and upgrading of existing ones; (2) improvement of environmental and public health conditions in settlements throughout the country; (3) mobilization of resources in the informal sector; and (4) distribution of government land. PRIDE is intended to increase access to land and secure tenure for the landless, who would otherwise be unable to access land for housing, agriculture, and other uses. Under the program, households and communities must undertake community assessments and form legally recognized community organizations. As of 2003 statistics, over 20,000 families have benefited from the program (daCosta 2003; Tindigarukayo 2004).

DONOR INTERVENTIONS

USAID’s Country Assistance Strategy (2010–2014) supports the GOJ’s agenda to increase agricultural revenues, diversify agricultural production, and improve access to markets and credit. USAID’s regional work, which includes Jamaica, involves a project on alternative dispute-resolution (including land disputes), legal-system efficiency, and improved access to the legal system. The project started in 2000 and was completed in 2004, with the main focus on providing technical assistance, training, and commodities to the Eastern Caribbean Courts to modernize the legal system and increase access to legal information (Sanjak 2003; USAID 2004; daCosta 2003; USAID 2009b).

USAID also has a sustainable land-management program designed to help the GOJ curb the destruction of the country’s natural resources. In rural areas, USAID supports alternatives to swidden (slash-and-burn) farming and the revitalization of tree crops (USAID 2007; USAID 2009a).

The IDB has been funding LAMP, as well as the five-year extension of the program granted in 2008. USAID has recently undertaken a review of LAMP, and the issue of land titling in Jamaica in general, in order to inform the agency’s consideration of whether to become engaged in the issue in some manner (Dunkley 2010).

Freshwater (Lakes, Rivers, Groundwater)

RESOURCE QUANTITY, QUALITY, USE AND DISTRIBUTION

Jamaica has internal renewable water resources of 9.4 cubic kilometers per year. Of this total, surface and ground water resources constitute 5.5 and 3.9 cubic kilometers per year, respectively. In 2007, the agricultural sector was the major user of water (49%). Domestic use accounted for 34% of water use, and industry for 17%. About 92% of water was withdrawn from groundwater sources and the remainder from surface water (World Bank 2009; FAO 1997).

Jamaica’s two major water storage facilities are both located in St. Andrew. These include the Mona Reservoir, which is fed by the Hope and Yallahs Rivers, and the Hermitage Reservoir, which is fed by Ginger River and Wag/Morsham River. These reservoirs have a storage capacity of 3.67 million cubic meters and 1.78 million cubic meters, respectively (FAO 1997).

As of 2006, 93% of the total population had access to improved water. Ninety-seven percent of the urban population and 88% of the rural population had access to improved water. Ninety percent of urban households and 47% of rural households had water piped to their home, yard or plot. One-third of the poorest households rely on standpipes for their water, and 30% obtain their water from untreated sources such as rivers (WHO and UNICEF 2008; GOJ 1999).

Jamaica’s surface water quality is threatened by the intrusion of seawater, contamination of groundwater and surface water from alumina plants, contamination of both groundwater and surface water by wastewater from agro-industrial waste, seepage from unlined solid waste dumpsites, and leaking underground petroleum-storage tanks. In some areas solid waste clogs watercourses (USACE 2001; IRC 2002).

Increasing population growth, food consumption, and water-use for domestic purposes have strained water resources in Jamaica. Declining water resources most dramatically impacts impoverished communities which, in turn, are more likely to colonize forested areas, further straining water resources. Demands for potable water often exceed water availability. In addition, water resources are unevenly distributed – the south has the greatest demand for water; however, the north has the greatest water supply (USACE 2001).

LEGAL FRAMEWORK

The 1963 Watersheds Protection Act governs the protection of watersheds and conservation of Jamaica’s water resources. The Act seeks to ensure that vital watershed areas are properly managed. In addition, the Act is intended to reduce soil erosion, maintain optimum levels of ground water, and promote regular flows in waterways. Implementation of the act is administered by the Natural Resources Conservation Authority (NRCA) (GOJ 2006a; GOJ 2003a; USACE 2001).

The 1996 Water Resources Act also establishes the Water Resources Authority (WRA) as the national agency in charge of regulating, allocating, conserving and otherwise managing Jamaica’s water resources. The Water Resources Act vests in the government the authority to reserve a source of supply for a public purpose; applicants for the abstraction and use of reserved water for a public purpose take precedence over competing applications and override existing abstractions (GOJ 1996b; FAO 2007).

An amendment to the 1949 National Irrigation Act now includes Water Users Associations (WUAs) as legal entities in the management and operation of all new or rehabilitated irrigation systems identified for construction under the National Irrigation Development Plan (GOJ 2003b).

TENURE ISSUES

The 1996 Water Resources Act provides that Jamaica’s water belongs to its people and that the government has an obligation to make water available to the population. According to the Water Resources Act, individuals may abstract and use water without a license if (1) the user has a right of access to the source of water, and (2) the water is required only for domestic use. In other circumstances, a license issued by the WRA is required. The Act eliminated ownership or possession of riparian land as a prerequisite to the claim and exercise of water- abstraction rights (GOJ 1996b; FAO 2007; Geoghegan et al. 2003; IDB 2002).

The GOJ’s strategy is to encourage private-sector participation in the urban and rural water sector where this is likely to benefit consumers and the country in general. Key areas for private investment include: improvements in the efficiency of operations and investment; technical and managerial expertise; access to new technology; and the injection of capital investment. The government expects that increasing private investment in the water sector will facilitate the transfer of risks and responsibilities of ownership from the government to the private sector and deliver a reliable and efficient service to the urban and rural sectors. Despite this recognition, private-sector participation in Jamaica’s water sector remains negligible (Springer 2005).

GOVERNMENT ADMINISTRATION AND INSTITUTIONS

The Minister of Water and Housing (MWH) is the primary coordinating agency in the water sector. MWH has overall policy, financial, and administrative responsibility for the water sector, including the National Irrigation Commission (NIC), the Water Resources Authority (WRA), the National Water Commission (potable water utility), and the National Irrigation Commissions (NIC) (IDB 2002; USACE 2001).

The NWC is responsible for water supply to urban areas throughout Jamaica and provides 75% of the population with potable water. The agency is also the largest provider of sewage services (USACE 2001).

The NIC is a government-owned company that is responsible for the operation, maintenance and development of publicly owned off-farm irrigation works. The WRA was established by statute to regulate the island’s water resources in 1996. The WRA has responsibility for management, protection and controlled allocation and use of Jamaica’s water resources (IDB 2002).

The Natural Resources Conservation Authority (NRCA) is responsible for managing watershed protection. Additionally, NRCA is charged with implementing the Watershed Protection Act. The NRCA develops watershed management policies, the most recent of which defines opportunities for Jamaican communities and government agencies to participate in the sustainable management and conservation of watersheds in Jamaica (USACE 2001).

GOVERNMENT REFORMS, INTERVENTIONS AND INVESTMENTS

The Jamaica Social Investment Fund (JSIF) is a limited-liability company that was established in 1996 as a component of the government’s national poverty-alleviation strategy. JSIF supports local water-resource improvement projects (JSIF 2008).

The National Irrigation Development Plan (NIDP) has proposed 51 irrigation projects over a 17-year period to be completed in 2015 (USACE 2001).

As of 2006, a Watershed Policy was under consideration. The draft policy provides for watershed management to promote the integrated protection, conservation and development of land and water resources in watersheds for sustainable use and for the benefit of the nation as a whole (GOJ 2006a).

DONOR INTERVENTIONS AND INVESTMENTS

The main external cooperation partners supporting the Jamaican government in water supply and sanitation are USAID, the Canadian International Development Agency (CIDA), the World Bank, the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB), and the European Union (EU).

From 2000 to 2005, USAID funded the Ridge to Reef Watershed Project for the sustainable development of the Great River Watershed. The project was designed to improve water and land-use management, and build a participatory process for all stakeholders. The project established mechanisms for more effective communication, coordination, and implementation of watershed management initiatives through the facilitation of the National Integrated Watershed Management Council (NIWMC) and the National Environment and Planning Agency (NEPA)’s Sustainable Watersheds Branch (ARD 2004; USAID 2006).

CIDA has invested in several water-services projects involving sustainable development planning, capacity-building in communities, and biological waste treatment (Springer 2005).

The World Bank funds the Jamaica Inner City Basic Services for the Poor Project, which includes the development of integrated network infrastructure for water and sanitation and the installation of in-house water and sanitation connections. The project will run through 31 December 2011. IDB funded a National Irrigation Development Program starting in 1998. The purpose of the program is to achieve a more efficient allocation of the country’s irrigation water resources and to contribute to increasing agricultural production and productivity in a sustainable manner. Over 125 projects island-wide were evaluated, and 51 of these projects were selected for implementation by 2015, at a cost of US $106.3 million. The program also proposes that the current irrigated area of 25,000 hectares be increased by 60% to 40,000 hectares. According to the National Irrigation Commission, which oversees the NIDP, 51 projects irrigating over 20,000 hectares of land are underway (World Bank 2006b; IDB 2002; Springer 2005; NIC 2010).

The Inter-American Development Bank has both recent and current projects focused on improving water resources in Jamaica. For example, the IDB completed the Water Resources Master Plan in 2008 and the Kingston Metro Water Supply project in May 2010 (IDB 2010).

Trees

RESOURCE QUANTITY, QUALITY, USE AND DISTRIBUTION

Originally, Jamaica was almost entirely covered by forests. Years of poor land-management have reduced the forest land by 50%. Jamaica’s forest land currently includes 339,000 hectares of land with forest cover and 188,000 hectares of other wooded land, such as plantations. Virgin natural forest remains only in areas that are difficult to access, such as mountain mist forests, and is largely comprised of tropical montane forest. Additional forest land cover is largely comprised of bamboo, mangrove, closed broadleaf, disturbed broadleaf, short open dry, swamp, and tall open dry forests. Forests comprise 31.2 % of Jamaica land area (FAO 2009; Evelyn and Camirand 2003).

Jamaica has 110,000 hectares of designated forest reserves, including Blue Mountain, Dry Harbour, Cockpit Country, and Dolphin Head. Of these, Blue Mountain/John Crow Mountain National Park is the most critical forest reserve (GOJ 2001; FAO 2009).

Jamaica is a net importer of timber and other forest products. Over 80% of the wood consumption in the country is for fuelwood or charcoal, although this percentage is declining due to the increased use of bottled gas for cooking. The country has a sawmilling industry, though it is modest and produces primarily plantation-grown sawn timber (FAO 2009).

Change in forest cover for the period 1990 to 2000 has been estimated at an annual loss of 5000 hectares. Much of the reduction in original forest cover over the decade can be attributed to an increase in coffee plantations. More recently, increases in bauxite mining, squatter settlements, illegal use of timber, and forest fires have also contributed to deforestation. Deforestation has been linked to flooding, soil erosion, destruction of wildlife and wildlife habitat, and decreased surface stream and river capacity (FAO 2009; Berglund and Johansson 2004; Evelyn and Camirand 2003; daCosta 2003).

LEGAL FRAMEWORK

The 1996 Forest Act provides the legal basis for the organization and functions of the Forestry Department. The Act specifies mandatory requirements for: (1) declaration and purpose of forest reserves and forest management areas; (2) national and local forest management planning; (3) inventory and classification of forest lands; (4) appointment and function of forest management committees; (5) determination of allowable cut; (6) establishment of nurseries and provision of seedlings; and (7) enforcement of forest protection measures.

Under the Forest Act, the Forestry Department is charged with: (1) sustainable management of forests in Crown lands or in forest reserves, and the effective conservation of those forests; (2) directing and controlling the exploitation of forest resources; (3) preparing and implementing a national forest management and conservation plan; (4) promoting the development of forests on private lands; (5) promoting, establishing and maintaining a forest research program; (6) establishing and promoting public education programs to improve understanding of the contribution of forests to national well-being and national development; (7) establishing and maintaining recreational facilities on forest lands; (8) promoting agroforestry and social forestry programs; (9) determining fees for licenses or permits; (10) preparing forest inventories and demarcating and maintaining forest boundaries; (11) controlling and supervising the harvest of forest resources; (12) granting licenses and permits; (13) compiling information concerning the use of forest resources; (14) protecting and preserving watersheds in forest reserves, protected areas and forest management areas; and (15) developing a program for proper soil conservation. The Forest Act grants the government authority to acquire private land for the purposes of forest reserves, in accordance with the terms of the Land Acquisition Act (FAO 2009; GOJ 1996a).

The Minister of the Forestry Department is entitled to declare any Crown land as a protected area, in accordance with criteria outlined in the Forest Act (GOJ 1996a).

The 2001 Forest Policy provides the mechanism by which the provisions of the Forest Act can be implemented, including community participation, public awareness and environmental education, and forest research. Every five years, the Conservator appointed by the Forestry Department is required to prepare and submit a forest management plan for each forest reserve and forest management area. These plans were not submitted. However, the 2009–2013 Strategic Forest Management Plan states that, over the next five years, local forest management plans will be developed, approved and implemented for at least 50% of the national area designated as Forest Reserves or Forest Management Areas (GOJ 2009b; GOJ 1996a; FAO 2009; GOJ 2001).

The 1991 Natural Resources Conservation Authority Act governs the protection and management of Jamaica’s natural resources. The Act established the Natural Resources Conservation Authority, which manages the country’s protected areas (GOJ 2009a).

TENURE ISSUES

According to the Forest Act, individuals may own land in protected areas, although the Conservator may assume control of the land if the owner does not comply with the regulations outlined by the Forest Act. Private landowners may also lease land within protected forest areas (GOJ 1996a).

According to 2000 data, of all forest-covered land, 65% is privately owned, 28% is publicly owned, and the remaining 7% is subject to other types of ownership (GOJ 2006a).

Licenses and permits are required for: harvesting timber on Crown lands; processing of timber and other forest products; sale of timber; sawmilling activities; removal of dead or damaged timber; research activities; recreational facilities; and any other purposes approved by the Conservator (GOJ 1996a).

No person may cut trees in a forest reserve unless they hold a license or permit for that purpose. Additionally, primary closed natural forest in forest reserves, national parks, or protected areas may not be harvested (GOJ 1996a; GOJ 2001).

GOVERNMENT ADMINISTRATION AND INSTITUTIONS

The Forestry Department is the lead agency for forestry management and also plays a critical role in watershed management (GOJ 2001).

The National Environment and Planning Agency (NEPA) functions as the lead agency for environmental management and land-use planning. The improvement of forest management is constrained by a variety of policy, administrative and institutional factors, including overlap and gaps in jurisdiction and legislation covering watershed and forest management, budgetary constraints and difficulty in fostering intergovernmental coordination among the 14 government offices, ministries, departments, authorities, commissions and boards that have statutory interests in forest and watershed management There is no clear designation of the agency responsible for carrying out the environmental rules and standards. Inspections and sanctions are uncommon, and overall enforcement of regulations is weak (Catterson et al. 2003; Geohegan et al. 2003; GOJ 2001).

GOVERNMENT REFORMS, INTERVENTIONS AND INVESTMENTS

In 1996 Jamaica approved its latest forest policy in a document titled “Forestry and Land Use Policy.” The policy lists 33 goals under subject areas including conservation and protection of forests and management of forested watersheds (FAO 2009).

The GOJ established two funds designed to support the sustainable development of Jamaica’s forest areas; the Jamaica Forest Management and Conservation Fund (proposed in the National Forest Management Plan) and Tropical Forest Fund will be supported by bilateral contributions, corporate sponsorship, and resource user/management fees, as well as multilateral contributions to debt reduction (GOJ 2009a).

The Spinal Forest Project, developed by the Environmental Foundation of Jamaica (EFJ), seeks to establish a forest along the central mountain core of Jamaica. This project will be administered largely by the Forestry Department (GOJ 2009a).

Beginning in 1992, the GOJ partnered with CIDA to implement the Trees for Tomorrow Project. The project seeks to increase the capacity of the Forestry Department to sustainably manage and conserve forests. The project focuses on forest inventories, planning, and training (Headley 2003; FAO 2009).

DONOR INTERVENTIONS AND INVESTMENTS

USAID’s Ridge to Reef Watershed Project (R2RW) began in August 2000 as a five-year US $8 million initiative with NEPA. The project was designed to improve the management of natural resources in targeted watersheds that are both environmentally and economically significant. The project’s goals included improving practices and capacity. Additionally, the action-plan framework identified as a primary goal the facilitation of economic development by establishing and promoting a Great River Brand for local agricultural and forest products. The project was instrumental in establishing mechanisms for more effective communication, coordination, and implementation of watershed management initiatives through the facilitation of the National Integrated Watershed Management Council (NIWMC) and the strengthening of the National Environment and Planning Agency (NEPA)’s Sustainable Watersheds Branch (Catterson et al. 2003; ARD 2004).

Minerals

RESOURCE QUANTITY, QUALITY, USE AND DISTRIBUTION

Jamaica ranks among the world’s leading producers of alumina (aluminum oxide) and bauxite. Other mineral commodities produced in Jamaica include gold, gypsum, lime, limestone, refined petroleum products, salt, cement, and other construction materials. The bauxite and alumina industry in Jamaica has historically been the second-largest foreign-exchange earner, generating more than US $500 million per year and contributing 60% of the country’s foreign revenues. The GOJ estimates that minerals lie beneath more than 70% of the country’s total land area. Onshore and offshore oil drilling has been inconclusive regarding the presence of oil deposits (Bermúdez-Lugo 2008; Berglund and Johansson 2004; UN-Habitat 2010).

The main bauxite deposits occur in the highlands. The bauxite in Jamaica has little overburden, making mining the ore cheap and easy (Berglund and Johansson 2004).

Mining operations are located in rural and semirural areas and provide a source of non-agricultural employment. Substandard mining practices have caused deforestation, soil degradation, and water pollution (Berglund and Johansson 2004; Catterson et al. 2003; daCosta 2003).

There are relatively few registered artisanal mining operations in Jamaica. Jamaica had approximately 140 registered small-scale mines in 1999, constituting about 5% of the mining sector, and employing about 1200 individuals. However, small-scale illegal mining, particularly of sand, is common in some areas of the country, including the Caymanas Plains and Rio Minho (Avila 2003; UN-Habitat 2010).

LEGAL FRAMEWORK

Key legislation governing the mining sector in Jamaica includes the 1947 Mining Act (as Amended), the 1983 Quarries Control Act (as Amended), the Minerals Vesting Act, and a series of implementing regulations. The legal regime for minerals (as expressed in the Minerals Vesting Act) distinguishes between minerals such as gold, bauxite and marble, which are governed by the Mining Act, and quarrying materials such as sand and limestone, which are governed by the Quarries Control Act (UN-Habitat 2010).

The 1947 Mining Act governs the manner and procedures for mining operations. The Act allows individuals and entities exploiting mining resources to obtain licenses and leases for mining activities. Those exercising mining rights must provide reasonable compensation to landholders where operations disturb the surface rights to the land. All licenses and leases and any transfers must be registered. Sales of minerals require a dealer’s license and are subject to royalty payments (GOJ 1947).

The Mining Act requires reclamation and restoration of bauxite mining areas. Programs for the reclamation of productive land require grasses and shallow-rooted crops to be planted for at least 10 years to improve soil fertility (daCosta 2003).

The 1983 Quarries Control Act, with subsequent amendments, was adopted to manage expansion of the quarry activity in Jamaica. The law sought to: bolster environmental protection; increase penalties for illegal activity; establish zoning; centralize control over quarrying industries; clarify the tax structure; and increase communication between government agencies (UN-Habitat 2010).

The 1991 Natural Resource Conservation Authority Act (NRCA) of 1991 provides licensing requirements for mining development (GOJ 1991).

TENURE ISSUES

Under the 1973 Minerals Vesting Act, minerals are vested in and subject to control of the GOJ. The state owns all minerals, and regulates the prospecting, extraction, and sale of minerals. Jamaican nationals and foreign persons and companies are eligible to apply for mineral licenses and leases. Fair and reasonable compensation is payable for all damages and for disturbance of the landowners’ surface rights, or for any damages done to livestock, crops, trees, buildings, or works. Private landowners have ownership rights to the land surface and to quarry materials, however, although quarrying operations are subject to state control. A quarry operator must obtain a license from the Ministry of Mining and Telecommunications prior to excavation, as well as a land lease if the land belongs to someone else (GOJ 1973; Berglund and Johansson 2004; UN-Habitat 2010).

Mining licenses are available for up to 25 years and may be renewed. Special leases are available for mining bauxite and laterite (GOJ 1947).

Illegal mining has been a notable problem in Jamaica, as has the high frequency of violations by mines that are legal and registered. Mining inspection and law enforcement have been inadequate, and industry operators have threatened and blocked the passage of government mining inspectors. Much illegal mining consists of sand quarrying on government land, often by small-scale operators. Reasons for continued illegal activity in the mining industry include that: penalties are too low compared to profits; judges are too lenient and seldom impose meaningful penalties; police support has been inconsistent; the costs of legally operating a mine or quarry are very high, and the market demand for low-priced, illegal mining products is strong; and in some cases small-scale illegal quarrying has gone on for generations and provides critical household income (UN-Habitat 2010).

GOVERNMENT ADMINISTRATION AND INSTITUTIONS

The Ministry of Mining and Telecommunications and the Natural Resource Conservation Authority are both involved in mining oversight in Jamaica. The Jamaican Bauxite Institute (JBI) is the government agency responsible for overseeing the bauxite and alumina industry (Berglund and Johansson 2004).

GOVERNMENT REFORMS, INTERVENTIONS AND INVESTMENTS

The Ministry of Mining and Telecommunications was created in 2008 to develop a competitive minerals industry focused primarily on the manufacturing of value-added products, contributing to national sustainable development, and existing in harmony with other land-users and segments of the economy (GOJ 2008b).

The National Industrial Policy (NIP) identifies opportunities for expanding the mining industry in Jamaica. The GOJ encourages foreign investment in the mining sector. By 2007, over US $1.4 billion was invested in the Jamaican mining sector (Dunn and Mondesire 2002; Morrison 2009).

Since 2003, the government has attempted to reduce illegal sand-quarrying in the Caymanas Plains and Rio Minho areas. In Caymanas Plains, the government began a push to regularize small-scale quarries by offering rights to government land and assistance with registration. To address illegal quarry activities in the Rio Minho area, the government established the Northern Rio Minho Monitoring Committee (Mines and Geology Division), charged with monitoring and regulating quarries and exposing illegal operations. This committee includes members of the National Environment and Planning Agency, the National Works Agency, the Police, the Jamaica Information Services, and the Mines and Geology Division (UN-Habitat 2010).

DONOR INTERVENTIONS AND INVESTMENTS

The Government of the Czech Republic, in collaboration with the Jamaican Mines and Geology Division (MGD), is currently supporting a mining development project. Project objectives include identifying non-metal mineral deposits for rapid economic development, assisting in improving quarry operations, and supplying the MGD with equipment (Mbendi 2009).

From 1995–2000, CIDA supported the Jamaican mining sector. The projects included training government officials to increase institutional capacity (Dunn and Mondesire 2002).