Overview

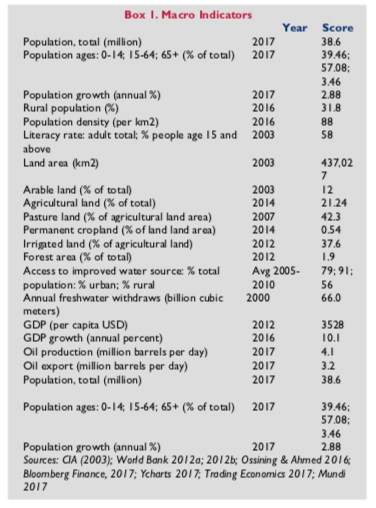

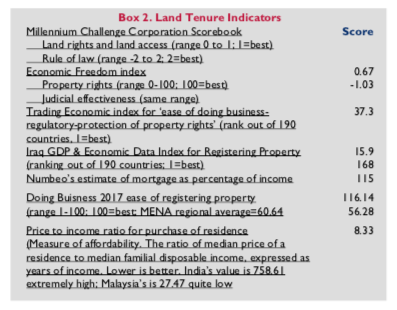

With some of the earliest known human settlements in the world, most of Iraq together with Kuwait, eastern Syria and southeastern Turkey constitute Mesopotamia, also referred to by historians as the ‘cradle of civilization’. Iraq has a surface area of approximately 437,072 square kilometers, making it slightly larger than twice the size of Idaho. It is bordered by Turkey to the north, Iran to the east, the Persian Gulf and Kuwait to the southeast, Saudi Arabia to the south, Jordan to the west, and Syria to the northwest. The country has a total land boundary of 3,650 km and a coastline of 58 km.

Topographically Iraq is divided into three zones: the highlands in the northeast (rising to approximately 3,000m); the desert in the southwest and west (elevation 600-900m); and the plains in the south-central part of the country. The plains are dominated by the Tigris and Euphrates river systems, which combine in the southeast of the country to form the Shatt al Arab waterway, a wide body of water which empties into the Persian Gulf. Only 1.9 percent of the total land area in the country is in forest and woodland, and desertification is an ongoing problem in Iraq’s dry, hot climate. Soil salinization, erosion and river basin flooding have impacted fertile agricultural lands over large areas of the country, and the deterioration of agricultural infrastructure has led to a decline in agricultural productivity, particularly since 2002 (Lucani 2012). Agriculture primarily exists as small farming units with low input-output systems, as farmers attempt to minimize costs related to land preparation, planting, and harvesting. As a result, yields are quite low. Crop agriculture is the primary income source for 75 percent of farmers, with the remainder dependent on livestock and mixed crop-livestock systems. Iraq’s main crops are grains, primarily wheat and barley, with tomatoes and potatoes grown in irrigated areas, and dates constituting a major cash crop (Lucani 2012).

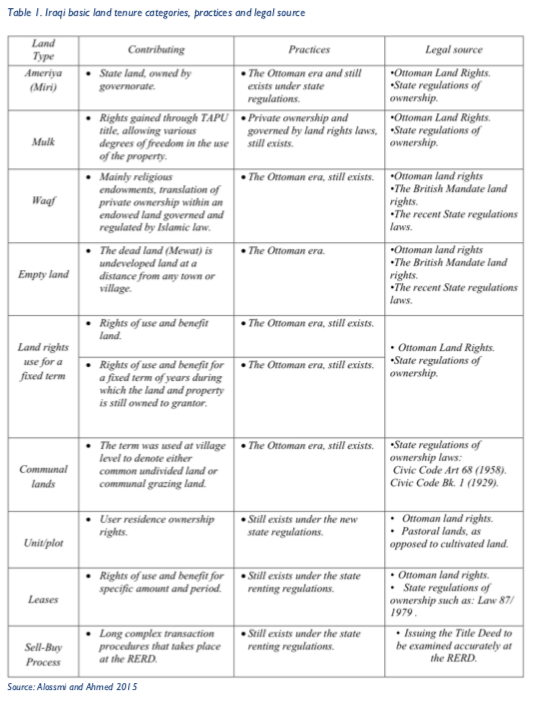

The structure of the land rights system in Iraq has deep historical roots, going back to the Hammurabi period (1810 BC – 1750 BC). The current tenure system is significantly influenced by the Ottoman period in Iraq (1534 – 1704 and 1831 – 1920) spanning some 400 years, followed by the British mandate period (1920 – 1932) (Baali 1960). In the Ottoman and British periods, the landholding structure was designed to reinforce political power through the provision of lands to individuals who were influential and supportive of the government in-place (RTI 2005; Baali 1960). The result was a great deal of land accumulation in few hands, and a peasantry that possessed very few rights in land. In the Ottoman period the land administration system known as TAPU (title deed) provided for both deeds and a land register, and lands were classified into categories. In 1974, the Real Estate Registration Law replaced the TAPU system, establishing Real Estate Registration Departments and creating an improved title issuing service.

During the Ba’athist period (1963 – 2003) a socialist ideology led to the implementation of a large-scale land reform in the rural tribal areas in which limitations on landholding size were enacted, and collective ownership and agricultural production pursued. In the late Ba’athist period supporters of the regime received government land, while at the same time Iranians and Kurds had land expropriated even though they held title (RTI 2005). In this period both rights to land and tenure security were used to punish and reward citizens. Processes for transacting property, registration and applications for improvements were quite lengthy but regarded as fairly effective; and as of 2005 approximately 96 percent of land owners indicated that their property was registered. Fewer than three percent of owners had mortgages, though (RTI 2005). With the deterioration of authority and institutions following the Second Gulf War, fraudulent titles have become increasingly common (RTI 2005).

Key Issues & Intervention Constraints

The Global Protection Cluster-Iraq (PCI 2016a) recommends the following as land and property priorities for intervention:

- Support needs to be provided to government for the restoration and replacement of civil documentation pertaining to land and property;

- A broader range of evidence beyond documentation, which supports claims to land and property needs to be legally recognized;

- Legal assistance regarding land and property needs to be provided to displaced populations;

- Government should be supported in efforts to expand internally dislocated persons’ (IDPs) access to adequate and affordable housing with tenure security, regardless of the land and property restitution remedy applied.

The Global Protection Cluster is an affiliation of interested organizations—donors, NGOs, INGOs, governments—that seek to coordinate response to particular problems. Donors can find participation in the Cluster to be useful for initiating, supporting and implementing specific programs and projects in Iraq. While the above list is for Housing, Land and Property Rights (HLP) in Iraq, the Cluster has a wide range of priorities, and needs additional support, engagement and direction setting from participants.

As a priority issue, IDPs currently seeking to return to their lands and properties face an uncertain legal, security and livelihood landscape, and most are unaware of their legal options and recourse. What is needed is a legislative and institutional ability to engage in a land and property restitution process (to include a variety of remedies) specifically for the 3.0 million people displaced due to the ISIS conflict. Without such an effort, the concern is that returnees will default to armed kin or local militias to resolve their land and property problems. The UN International Organization for Migration (IOM) is working with the Iraqi government on the need for this legislation, and what it might look like. Additional donor support is needed to work with the government and IOM on the kinds of restitution laws and institutions that have worked well elsewhere, and what kinds of remedies should be considered for secondary occupation, dispute resolution, and damaged and destroyed HLP.

Government and donor assistance is needed in the process of return and reclaiming land and properties in areas that have been retaken from ISIS. Donor involvement is needed for a robust awareness raising campaign for returnees regarding what to do when they return to find secondary occupants, disputes, damage or destruction. Given the pervasiveness of mobile phones and IDP familiarity with social media, there is a significant opportunity to ‘push’ this information to the IDP community. Mobile legal clinics, similar to, or supporting IOM’s ‘community policing’ efforts are needed in areas of return, given that large-scale returns will take place prior to the establishment of functioning, effective state institutions for resolving land and property problems.

In a number of areas that experienced forced dislocation under ISIS, returnees are confronting the return of those who were dislocated from the same lands under the Ba’athist period (or their descendants). This results in the destruction of properties by the Ba’athist era dislocatees so as to discourage return by ISIS dislocatees. Particular attention is needed on this type of land and property dispute, given that a minority of returnees are aware of the existence of the Commission for the Resolution of Real Property Disputes (CRRPD) created to attend to Ba’athist era expropriations. Donor support is needed for awareness raising among returnees and re-emerging Iraqi institutions regarding how to resolve such disputes within the CRRPD, including the derivation of a ‘fast track’ capability.

The CRRPD is a large endeavor involving a set of multiple institutions and many procedures to work through to reclaim lands and properties. There are strong preferences within civil society that it be made much quicker, more efficient, and with far fewer steps to effectively serve the intended population. Donor involvement is needed to significantly streamline the operation of the CRRPD, and, in particular, to expand the types of remedies to include more than simply return to one’s HLP or minimal compensation in a ‘take it or leave it’ approach.

There is a significant connection between current IDP returns and militia membership. Local militias in Iraq emerge in the absence of effective state institutions, are one of the very few employment opportunities in areas of return, and provide the much-needed security for civilian populations. Many if not most of these militias are not ideological and focus on security, area control and occasionally revenue generation. While they are often based on sect, ethnicity or geography, efforts by government and donors to coordinate, include, involve or co-opt local militias instead of confronting them, will very likely prove worthwhile. Donor support is needed to derive and implement ways to communicate with and include militias in a recovering Iraq—institutional development, employment and capacity building, dispute resolution, connections to state institutions and reintegration.

Land and property rights for women remain an ongoing challenge in Iraq, particularly for female head of households with children following the death or disappearance of a spouse. With only secondary rights to HLP, women usually lose and have few alternatives in a postwar environment. Greater attention is needed on legal, institutional, customary and tribal efforts to ensure that access to land and property (or alternative remedies) are equally available to women. Donor support is needed to establish forms of legal support for women, in particular women heads of households, that can specify how to retain rights to HLP. Support is also needed for working with tribal, religious, and militia leadership to see what forms of customary institutions can play a role. Support is needed in the derivation and implementation of female-specific HLP remedy options.

A negotiated border demarcation between the Kurdish region and the rest of Iraq is needed. Negotiations as to the status of the Kurdish region are also needed. The recent referendum on separation and the subsequent repercussions has made this issue particularly important. Donor support is needed to assist both the regional and federal governments in negotiations regarding status, borders, and management of oil and gas resources. The US has particular legitimacy with both regional and federal governments and can provide support and incentives to a negotiation process.

Oil and mineral rights are considered property of the state and under federal government control for the benefit of the people. Iraq has laws governing the administration of oil that date from 1942 to 1997. The country initially drafted a federal oil and gas law in 2007 to update the older legislation. This draft was submitted to Parliament in 2011 but it was never considered. Iraq needs to give greater attention to oil and mineral rights and update older legislation so that a widely agreed upon version can be promulgated in order for Iraq to take advantage of international investment opportunities and gain the needed revenue for reconstruction and recovery. Donor assistance is needed in resolving disagreements about the draft law that currently exist in different sectors of civil society, government and international investors. Even the sponsorship of conferences, workshops and consultation processes would be very worthwhile.

Iraq is a downstream country in the Tigris-Euphrates riparian system. The country is water stressed given its rising population, lack of environmental regulatory enforcement, increased salt intrusion in the river system, desertification, and an aging, damaged water infrastructure. Advances in water technologies, institutions, and ways of organization involving local user groups should be considered for application in the country. In this regard donor support is needed for: rebuilding components of the water infrastructure system; for training and capacity building in hydrology and the management of water for arid regions; and in coordination efforts with upstream states.

Summary

The ancient history of human settlement in Iraq means that forms of land rights associated with settlement in the country are likely among the oldest in the world. This has created both problems and opportunities. Problems, in that certain  aspects of older land rights systems, coming from both from within the country and outside over time, still influence how land rights operate today, providing for a certain degree of confusion and ‘legal pluralism’ (different laws for different people). In addition, laws from different eras are aligned with the governing ideology of their respective time periods and do not always reflect the current legal environment, problems or aspirations of the country. Opportunity, in that such a history provides a rich source of legal land concepts, techniques, institutions and experience that will be needed in order for land and property rights to contribute robustly to Iraq’s recovery and economic development.

aspects of older land rights systems, coming from both from within the country and outside over time, still influence how land rights operate today, providing for a certain degree of confusion and ‘legal pluralism’ (different laws for different people). In addition, laws from different eras are aligned with the governing ideology of their respective time periods and do not always reflect the current legal environment, problems or aspirations of the country. Opportunity, in that such a history provides a rich source of legal land concepts, techniques, institutions and experience that will be needed in order for land and property rights to contribute robustly to Iraq’s recovery and economic development.

Of significant influence on Iraq’s land rights are the many waves of forced dislocations that have occurred over the centuries, particularly in recent decades. These large-scale dislocations, combined

with multiple ethnicities and sects occupying specific areas of the country, make current efforts at land and property conflict resolution quite difficult. Claims from previous dislocations clash with those from more recent dislocations and are overlain on ethnic territorial claims.

Currently, land and property restitution is a priority for the government and donor community active in Iraq. Three separate restitution processes are underway, based on the period of dislocation. The Commission for the Resolution of Real Property Disputes (CRRPD) operates a restitution process to attend to Ba’athist era expropriations from 1963 to 2003. Decree 262 and Order 101, along with the Anti-Terrorism Law making secondary occupation unlawful, are intended to manage restitution for the dislocations that took place during the war between the then Iraqi state and coalition forces. However, the just under 3.0 million IDPs currently dislocated by the war with ISIS do not presently have a specific set of laws or institution to facilitate returns, and this should be a priority of the government and international community in the near-term. This is because land and property restitution is a long process, fraught with disputes, less than perfect remedies, and tenure insecurity.

Although a great many Iraqis are farmers and pastoralists, oil production is responsible for 60 percent of the country’s GDP, 99 percent of exports, and 90 percent of government revenue (UNDP 2017). Yet there is no overall law to regulate oil and gas production, rights, and investment. A draft law has stalled due to political division and disagreement over what rights Baghdad will have versus the regions, and the role of foreign investors.

Water will be an ongoing concern in the country. With the population growing and freshwater resources declining, there is no Tigris-Euphrates agreement among the countries with interests in the river system. And with water data regarded as a state secret in Iraq and the other basin states, planning for water use and development is extremely difficult and subject to error, overly broad estimations, and shortages.

There are a number of recommendations for the land sector that can be considered by the government and its international partners. Land restitution along with other remedies needs significant ongoing attention. There are new techniques for mass claims processing that should be considered, in order to attend to land and property issues as quickly as possible so as to reduce the prospect for instability.

In this context, particular attention is needed on issues of land and property rights for women, especially given the now much larger proportion of female-headed households after the wars over the past decade. There are numerous components to restitution processes that can be supported separately by interested donors and government offices—from awareness raising, to working with forms of alternative dispute resolution and tribal law, to greater alignment between laws, and assisting with documentation systems.

Land

LAND USE

Land use in Iraq has been strongly influenced by its role in the economy along with the country’s military conflicts, population relocations, and government interventions in control over agricultural production (Schnepf 2003). From a total national area of 47.3 million ha, 34 million ha (77.7 percent) is not agriculturally viable under present conditions. Forest and woodland comprise less than 0.4 percent of the country and are located along Iraq’s northern border with Iran and Turkey. Approximately 9.5 million ha (22 percent) is devoted to agriculture, however approximately half of this is of marginal utility and is used exclusively for seasonal livestock grazing—primarily goats and sheep. Tree crops comprise approximately 340,000 ha of primarily grapes, olives, figs and dates, with the latter being most prevalent. Most tree crop production is located in the vicinity of Karbala (Schnepf 2003). Field crops include vegetables, cereals, pulses and fruit, with the areas under cultivation at any given time varying with market and weather conditions, but averaging between 3.5 to 4 million ha. Grains constitute 75-85 percent of all cropped area—primarily barley and wheat (Schnepf 2003).

Cropped land use in Iraq can be divided into: the central-south irrigated zone, which produces fruits, vegetables and cereals; and a northern zone which is rain-fed and produces winter grain. A particularly productive area in the foothills of the Kurdish autonomous region produces about one-third of the country’s cereal production under rain-fed conditions. Other than this, rain-fed crop yield is generally low and varies with rainfall. The rest of Iraq’s cereal production exists in the irrigated zone along and between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers (Schnepf 2003) (Figure 1). In general, there is only one cropping cycle per year although there is some multiple cropping of vegetables under irrigation. The irrigated areas in Iraq’s central – south region have been affected by salinization throughout its history due to a saline water table. As a result, even a small over-irrigation brings the saline water to the surface (Schnepf 2003).

Livestock are grazed throughout the agricultural zones as well as in areas used only for pastoralism, while poultry production takes place near urban centers. As a result of UN sanctions beginning in 1990, the poultry and livestock populations have declined significantly due to the conversion of rangeland to grain crops, together with the decline in feed grain imports and veterinary medicines.

The 1991 Gulf War damaged the irrigation and transportation infrastructure, to the degree that agricultural productivity declined significantly. Salinization then expanded across much of the irrigated area in the country’s central and southern regions, with these then becoming much less usable. Rural labor shortages after the 1991 war resulted in less area under agriculture—with much of the shortage due to the departure of foreign guest workers (Schnepf 2003). In an attempt to manage land use and agricultural productivity after the war, the government raised the official price of major field crops and expanded the area to be put under cereal crop production in the north of the country. The government also confiscated land from farmers who did not meet production quotas. Rising food prices and government incentives led farmers to expand cropped areas primarily by bringing under cultivation lands on fragile hillsides and marginal pastureland—with record areas under crop agriculture peaking in 1992 and 1993 (Schnepf 2003). A drought from 1999 to 2001 that affected much of the Middle East significantly impacted agricultural output in Iraq, with cereal production in the rain-dependent north particularly affected (Schnepf 2003).

LAND DISTRIBUTION

Current data on land distribution is scant. Multiple waves of dislocation have significantly reworked land distribution in the country, and with returns and dislocations still ongoing, it is difficult to get a sense of current distributions.

LEGAL FRAMEWORK

The legal framework for land rights in Iraq draws on multiple sources and ways of operating that have evolved over considerable time. Islamic law and Ottoman era law continue to influence the legal framework for land in Iraq, as does Egyptian and French law. In the 20th century Iraq blended in elements of the civil law tradition and produced its own Civil Code (Stigall 2008). Thus, Iraqi law is a blend of Western and Middle Eastern legal traditions. Presently Iraq embraces the civil law system as do other countries in the Middle East.

For outside investors, three items are important in Iraq’s legal framework:

- The category of the land needs to be identified and certified by a local land office;

- The three-year timeframe for miri land held under the tasarruf category to be either used or forfeited is important (Wiss and Anderson 2009).

- The American-run Coalition Provisional Authority (CPA) introduced a series of regulations that has made Iraq decidedly pro-outside investor, however there is a lack of detailed analysis of these regulations and their implications for foreign investment, with the exception of Siddiqui (2013).

Currently the land laws operable in Iraq include:

Resolution No. 333 Promulgating Law No. 42 of 1987. This legislation is concerned with the reorganization of agrarian ownership under reclamation projects. The law is focused on the reorganization of land ownership for lands subject to agricultural projects. It also provides remedies for compensation to land owners for expropriation.

Resolution No. 176 of 1993 Promulgating Law No. 18 of 1993 Relative to the Body of Administration and Investment of Awaqf Properties. The resolution establishes the ‘Body of Administration and Investment of Awaqf Properties’ that is legally, financially, and administratively independent, but connected with the Ministry of Awaqf and Religious Affairs. The body administers and develops land and property received as an endowment and acts as a council for all issues in terms of the administration and investment in Awaqf (also known as waqf) properties. The body is managed by a council comprising the Minister, several experts, three lawyers and officials from government.

Iraqi Company for Contracts for Land Reclamation (Law No. 116 of 1981). The law establishes the Iraqi ‘Company for Contracts of Land Reclamation’ under the Council of Ministers. The Company implements reclamation projects and acts as a contractor for reclamation projects. The Company is charged with carrying out its duties both inside and outside Iraq. The Company can sell and lease reclaimed lands and the properties of the company are considered ‘state domains’.

The Agrarian Reform Law No. 117 of 1970. Comprising five chapters and 52 articles, this extensive law covers a variety of agricultural land ownership issues, including the maximum size limit of lands that can be owned privately without authorization. The Agrarian Reform Authority can requisition lands above the stated limit and stipulate the forms of compensation that the owner of the requisitioned excess land is due. The Authority takes over the responsibilities of the survey committees regarding lands not yet surveyed, and those lands against which survey decisions are still pending. The Authority will distribute agrarian reform lands to peasants both individually and collectively.

Law of 2013 Confirming Ownership of the Agricultural Lands and Orchards Excluded from the Adjustment Acts. This law operates within the Municipality of Baghdad and deals with orchards and agricultural lands that were excluded from previous settlement acts or are otherwise of unresolved ownership status. The Law focuses on urban development that takes place on agricultural and orchard lands that have become unsuitable for agriculture due to urban development. The Law establishes the ‘Land and Expropriation Committees,’ which were initially promulgated by the Agrarian Reform Law of 1970. The Committees determine the rights over such lands and remove the definition of ‘agricultural land’ if in the old registers of the city they were not officially designated as ‘agricultural land’.

Law No. 2 of 1983 on Pasture. This law intends to manage pasture lands by planning grazing according to scientific approaches, and engaging in the protection of natural vegetation and water resources, and the organization of their use. The Law covers state-owned lands allocated for pasture. The Law states that the Ministry of Agriculture and Agrarian Reform is to regulate and organize livestock movements according to seasons and regions. The law prohibits the drilling of artesian wells and cutting plants in pasturelands.

Resolution No. 150 of 12 October 1997 Concerning the Sale of Plots of Land for Housing Owned by the State to Farmers. The Resolution stipulates that state-owned land not burdened by ‘disposal rights’ shall be sold to farmers, and pre-existing agricultural contracts are revoked and pre- existing rights extinguished. The Resolution provides limits of the allocation to farmers — not more than 1,000 m2 with no house and 2,000 m2 for a plot with a house.

Resolution Relative to Corporeal Compensation for Appropriated Real Estates and Amortization of the Right of Disposal of Vacant Agricultural Reform Lands, No. 90 of 1996. This law provides for compensation for the alienation of agricultural land, with alternative land as a first priority and cash compensation as a secondary priority. The law also prohibits compensation in kind or cash for certain types of land.

Resolution to Prevent Alienating of Estate Property of Iraqi Citizens who left Iraq, No. 21 of 1996. The resolution stipulates that the transfer of real estate owned by Iraqi citizens who left the country is to be prevented in all cases.

Resolution Concerning the Alienation of Real Property within the Boundaries of the Master Plan of Baghdad, No. 157 of 1994. This resolution stipulates that the transfer of real estate within the boundaries stipulated by Master Plan for Baghdad or the Master Plans of Aqdiyas and Nahiyas within the Governorate of Baghdad of a ‘certain type’ (undefined) shall not be registered unless the person receiving the transferred property was recorded in the census of 1957 or any previous census in one of the regions within the Baghdad Governorate before the creation of the Sallah Al-din Governorate. The rule does not apply in cases of inheritance of property due to death.

Resolution Concerning Agricultural Land. Unofficial title, No. 211 of 1991. The resolution stipulates that agricultural lands owned by the state which are cultivated by persons themselves or through others, shall be considered as property of the state with no compensation due, and shall be registered in the name of the Ministry of Finance as ‘pure’ property. The Ministry of Agriculture shall dispose of such lands in accordance with laws and regulations in force.

SECURING LAND AND PROPERTY RIGHTS

Land tenure security is significantly low in many areas of the country due to the recent conflict with ISIS, and the resulting dislocations, secondary occupation, and temporary residence. This is compounded by the tenure insecurity experienced by returnees from earlier displacements, and those they interact with in their attempts to reclaim land and property. The result is competing claims, use of militias to secure and enforce claim assertions, and ethnic and sectarian claims merging with individual and family claims— with no widely agreed upon ways to resolve these. In addition, the conflict-related surge in falsified land and property documents, together with institutional, authority and enforcement deficits further compromise tenure security for many.

While the statutory land administration system legally covers the entire country, the system is centralized and administration and enforcement in more peripheral areas is difficult. Recent research among IDPs indicates that many Iraqis do value statutory documents and the state system, but more for proving tenure status in the future, and less so for securing rights in the present (DDHLP 2017).

INTRA-HOUSEHOLD RIGHTS TO LAND AND GENDER DIFFERENCES

The distribution of land by gender in Iraq is quite skewed, with 26.2 percent of land in the country owned by women, and 73.8 percent owned by men (FAO 2017). Women face notable difficulties in re- claiming land and property after a forced dislocation. This becomes particularly difficult when the property in question is in the name of a missing or deceased male family member. And it can create problems when there is no documentary evidence of the relationship in the woman’s possession, or documents attesting to the male kin’s death or disappearance do not exist, resulting in an inability to claim the relevant property (PCI 2016b).

The Housing, Land and Property Sub-Cluster (within the Protection Cluster) intends to give attention to documenting the challenges faced by women in pursuing their land and property rights, and will develop guidance for women on the reclaiming of their property. Women’s NGOs are also to be supported so that they can provide legal assistance to women (PCI 2016b).

LAND ADMINISTRATION AND INSTITUTIONS

The institutional structure pertaining to land in Iraq broadly comprises six ministries and local boards (IMP 2016).

The Ministry of Agriculture’s mandate since the Agrarian Reform Law No. 30 of 1958 has been to pursue the best investment in agricultural lands, and stability in agricultural relations for the country. The Ministry supervises the implementation of legislation for agriculture regarding farm ownership, transaction of farmland and patterns of agricultural land possession rights (Al-Ossmi and Ahmed 2016).

The Ministry of Justice was given renewed authority under the CPA, and the resulting law (No. 18) of 2005 included in the Ministry’s mandate the supervision of the real estate registration departments (Al- Ossmi and Ahmed 2016).

The Ministry of Housing and Construction is the national housing authority and works with local government units at the governorate level to establish housing programs. A National Housing Office represents the Ministry in the private sector. The ministry is responsible for implementing national housing plans (Al-Ossmi and Ahmed 2016).

The Ministry of Municipalities and Public Works is responsible for making national policy relating to municipal matters, including the implementation of facilities for cities. Within this Ministry the General Directorate of Urban Planning deals with urban planning at the local level (Al-Ossmi and Ahmed 2016).

The Physical Planning Commission is a local level division of the General Directorate of Urban Planning and is the regulatory board for urban land use working through the local Municipality Offices. The Physical Planning Commission is tasked with monitoring and supervising the implementation of local land use regulations and development (Al-Ossmi and Ahmed 2016).

The Municipalities Offices are the local government department of the Ministry of Municipalities and Public Works and deals with the implementation of development within cities and surrounding villages as designated by the cities’ master plan (Al-Ossmi and Ahmed 2016).

COMPULSORY ACQUISITION OF PRIVATE PROPERTY RIGHTS BY GOVERNMENT

Ba’athist-era land expropriations by government were extensive and continue to be a source of numerous land disputes and ethnic animosity. The land acquisitions primarily took place in the north of the country among ethnic Kurds, Turkomans, and Assyrians in order to solidify control over valuable oil and arable lands and punish groups opposed to the government. Based in Ba’athist laws, the expropriations involved hundreds of thousands of people, and were followed by an Arabization policy to fill the vacated land with Arab settlers (Mufti 2004). In addition, the Algiers Agreement of 1975 led to the forced dislocation of ethnic minorities to collective townships where they were not allowed to register their assigned parcels in their own names (PCI 2016a).

While the prospect of compulsory acquisition of private property is a concern for foreign investors in Iraq, the law is clear that compensation must be provided. As well, the Iraqi constitution attempts to strike a balance between needs of the individual and those of the state and protects tasarruf rights holders (who comprise approximately 70 percent of all land in Iraq) from expropriation without compensation (Wiss and Anderson 2009). The issue would be then if and how such laws are enforced, and the forms and amounts of compensation.

LAND DISPUTES AND CONFLICTS

Iraq’s multiple waves of displacement over a period of 40 years have created numerous complex land and property conflicts. Short and long-term displacements have resulted from expropriation by the Ba’athist regime, terrorism, military operations, sectarian violence, and economic difficulties (Isser and van der Auweraert 2009). Official displacement of Iraqis of ethnic Persian descent from their lands began in 1979 and lasted into the 1980s, with the property then sold on to Ba’athist supporters, and then often resold at a profit. Subsequent to the end of the Ba’athist regime in 2003 many of those who were displaced, or their descendants, have attempted to return to reclaim their lands. Similar official dislocations took place among the Kurds and Turkmen in the vicinity of Kirkuk (RTI 2005). Displacement of land and property during and subsequent to Iraq’s more recent conflicts have affected millions, with the current number of displaced due to the ISIS war approximating 3.0 million, and an additional 231,000 registered refugees from outside the country at year end 2016 (UNHCR 2017). As this population now tries to return, they are encountering those who were displaced in the Ba’athist era seeking to return to the same lands, with the inevitable conflicts difficult to resolve peaceably given the absence of institutions to do this in ISIS retaken areas.

The agrarian reform efforts of the 1970s have also generated land and property conflicts between those who lost land and those who currently own it. A 1970 law reduced the maximum size of landholdings to between 10 and 150 ha of irrigated land, and between 250-500 ha of non-irrigated land. Holdings above these maximums were often expropriated. In 1975 an additional reform law sought to break up the large estates of Kurdish and tribal landholders, resulting in expropriations and then disputes once the Ba’athist regime ended. Additional expropriations worsened the Ba’athist government’s land rights, management and conflict problems, and resulted in the government coming to hold a large percentage of arable land which subsequent to its fall became contested.

With the fall of the Saddam Hussein regime in 2003, the Iraqi Property Reconciliation Facility was established as a land and property dispute resolution mechanism, and this was then succeeded by the Iraq Property Claims Commission (IPCC) in 2004. The specific purpose of the IPCC was to resolve disputes that arose from the Arabization policy between 1968 and 2003. The effectiveness of the IPCC has been uneven, however, due to an unawareness among the affected population, the challenge of handling the large number of claims, and the lack of enforcement for claims that have been decided (PCI 2016a; DDHLP 2017).

The Iraqi Civil Code contains the primary laws dealing with land and property and hence is the primary source of law regarding restitution and other remedies associated with forced displacement (Stigall 2009). Stigall (2004, 2008, 2009) describes the property rights aspects of the Civil Code in significant depth. There is a debate, however, as to whether the Iraq Civil Code is up the challenge of land and property restitution in Iraq, versus the need for other laws and specialized judicial mechanisms. Stigall (2009) argues that elements of the Civil Code are well up to the task of legally engaging the needed conflict resolution and restitution process, while certain UN agencies argue that the need for quick, large-scale restitution of land and property is best handled by additional laws and a separate commission. In one sense both are correct, in that while the Civil Code does possess the means, depth and respect to legally manage the nature of the land and property conflicts currently besetting the country, particularly those that will emerge with returnees from the ISIS conflict, the logistics of applying the law quickly for very large numbers of conflicts, needs a special mass claims restitution process conducted by an independent commission outside of the mandate of the IPCC.

On the part of the Civil Code, the complete protection of private property is provided for. Pertinent to the issue of displacement and restitution, the Civil Code stipulates that one does not lose ownership of land and property through non-use. As well, any possession of land and property obtained through coercion or ambiguity is countered in Iraqi law, and applies to those who have lost land to secondary occupation through violence or deception (Stigall 2009). Thus, there is no legal recognition of a militia member who occupies land by force. As well, Civil Code articles 192 to 201 provide remedies for usurpation and misappropriation of land and property (Stigall 2009).

Other legal devices in Iraq also play a role in conflict resolution. Then Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki issued a ‘general eviction order’ providing for a one-month time frame beginning in August 2008 by which all occupation of houses of displaced persons must be vacated or face eviction. Enforcement of this order took place with a large-scale eviction and property restitution effort, and the Iraqi army was tasked with evicting squatters, facilitating return and restitution of land and property (Stigall 2009). Of relevance to Iraq’s large internally displaced population is Iraq’s Law No. 20 of 2009 — Compensating the Victims of Military Operations, Military Mistakes and Terrorist Actions. This law seeks to provide compensation for violations of land and property rights due to military operations. However, many Iraqis cannot pursue this compensation without the assistance of a legal expert. Article 140 of the Iraqi Constitution of 2005 sought to resolve long-standing issues involving disputed lands and territories that primarily affect minority groups. A political impasse regarding the implementation of Article 140 has instead frozen the land allocation process in the areas of concern (PCI 2016a).

Some Iraqi laws act to inhibit the ability of the Civil Code to provide legal redress for dispossession. The Land Registration Law—which is separate from the Civil Code—can allow the transfer of land and property in some cases of coercion. As well, Article 17(1) of the Lease Law, No. 87 of 1979, which supersedes the Civil Code, provides for eviction for nonpayment of rent after a prescribed time period; and Article 17(7) stipulates that land and property uninhabited for more than 45 days can result in eviction (Stigall 2009).

On the part of the UN agencies that argue for a separate legislation, process and institution able to handle mass claims, considerable success has been experienced with specialized techniques able to quickly categorize conflicts and claims according to a variety of criteria, allowing for a single legal decision to be made for an entire category (Haersolte-van 2006; Holtzmann and Kristjansdottir 2007)

TENURE TYPES

Land rights in Iraq have developed over centuries, incorporating legal land concepts of a number of countries and cultures. Land in Iraq has traditionally been organized into categories derived from Sharia law that include: mulk (privately owned), waqf or awaqf (charitable trust land), matrukah (publicly owned), mawat (unused land), and miri (land that is state owned but possessed by an individual. While most land is classified as miri, this category is not well articulated in Sharia law, with the result being that it has been regulated by state code. And while miri land is technically owned by the state, it can be possessed and used by individuals who retain what are known as tasarruf rights, which is the right to exploit, use and transfer the land. Over time the difference between absolute ownership rights and tasarruf rights has narrowed to the extent that they are now essentially insignificant in ordinary business matters (Wiss and Anderson 2009).

that is state owned but possessed by an individual. While most land is classified as miri, this category is not well articulated in Sharia law, with the result being that it has been regulated by state code. And while miri land is technically owned by the state, it can be possessed and used by individuals who retain what are known as tasarruf rights, which is the right to exploit, use and transfer the land. Over time the difference between absolute ownership rights and tasarruf rights has narrowed to the extent that they are now essentially insignificant in ordinary business matters (Wiss and Anderson 2009).

Communal lands are those lands around a village that are commonly used by village members for grazing, firewood collection, etc. ‘Unit/plot tenure’ refers to a form of residence rights that are close to ownership rights. Leases are also a form of tenure in Iraq, with variations in terms and time periods. Table 1 summarizes the different forms of tenure, the practices under which they operate, and their legal sources.

The Ottomans created a title deed system in which miri land was issued deeds in the name of the state in order to counter the power of sheikhs who asserted control over income from miri lands. Following the socialist revolution in 1958 the government claimed all large landholdings, registered them as miri land, and redistributed them to cooperative societies and individuals in smaller parcels (Wiss and Anderson 2009).

The Iraqi Civil Code stipulates how property rights such as tasarruf are regulated, and a couple of important aspects of tasarruf are worth noting. A person in possession of miri land is entitled to tasarruf rights, which can be used as security for a loan. However if a tasarruf holder leaves land unused for three years without cause, rights to the land are forfeited. With the death of a tasarruf holder the rights are passed to the deceased’s heirs. If the heirs do not accept the tasarruf, it is then auctioned off (Wiss and Anderson 2009).

KEY LAND AND GOVERNMENT INTERVENTIONS

The Ottoman Land Code of 1858 was one of the first government interventions that sought to regularize land rights by establishing categories of landholding, and required surveys and registration of holdings. But by World War I only limited land registration had been achieved and land titles continued to be insecure, especially under tribal tenure systems through which the state retained ownership and tribes were allowed use rights (Metz 1988). Beginning in the early 1930s the Iraqi state pursued a number of land reform interventions in attempts to deal with acute land distribution problems (Metz 1988). This included resettlement and reclamation efforts in the 1940s, and settlement on state land for certain individuals together with programs of development in the 1950s.

The 1958 Iraqi Agrarian Reform Law attempted to provide a remedy for the large inequities in landholdings. This included the inequity of opportunity for acquiring land during the Ottoman rule between 1514 and 1918 which continued under British rule. This inequity resulted in approximately 80 percent of the land being owned by less than two percent of the population. The 1958 law was a landmark intervention in the history of Iraq and promised change from land-based feudalism toward private holdings (Al-Yasiri 1965). However, the results were chaotic in rural areas because the government at the time lacked the capacity for effective implementation. As noted in the above section ‘Land Disputes and Conflicts,’ two additional land reform interventions in the form of a 1970 law and a 1975 law sought to breakup large landholdings. Despite the intention of these laws, other ongoing government interventions resulted in the government gaining possession of large areas of agriculturally productive land.

In the 1980s intervention in the land sector was incoherent. First the government turned to land collectivization, and by 1981 had established 28 collective state farms that cultivated approximately 180,000 ha. In 1983 the government then produced a law encouraging local and foreign Arab investments in leasing larger plots of land from the government. And by 1987 the government produced plans to re- privatize agricultural land (Metz 1988).

More recently government intervention has focused on land and property restitution. To attend to displacement resulting from the conflict between 2003 and the onset of the ISIS incursion in 2014, Decree 262 and Order 101 were issued to facilitate return and claims, involving financial incentives to solve claims, along with a reiteration of the Anti-Terrorism Law that secondary occupation is unlawful (Isser and van der Auweraert 2009).

DONOR INTERVENTIONS

As noted above, one of the more robust donor interventions in the land sector began in 2004, when the Coalition Provisional Authority established the Iraq Property Claims Commission to attend to the Ba’athist era dislocations. This was then replaced by the Commission for the Resolution of Real Property Disputes (CRRPD). At present, donor interventions in the land sector focus primarily on facilitating return of IDPs to ISIS retaken areas. The UN’s International Organization for Migration (IOM) has a lead role in providing a wide variety of assistance with land and property assessments, legal assistance, and community stabilization both in locations where IDPs reside while dislocated and in areas of return (IOM 2016, 2017). UN Habitat and the Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC) are also engaged in a variety of projects to support returns of IDPs to locations of origin.

Generally, donor interventions in the land sector are coordinated under the Housing, Land and Property Rights Sub-Cluster, operating under the Global Protection Cluster (PCI 2016b). The Sub-Cluster engages in ‘mapping’ of key actors and areas of work relevant to land and property issues within 1) the humanitarian sector, 2) those engaged with early recovery, 3) development partners and, 4) government partners including the Ministry of Migration and Development, Ministry of Justice, Ministry of Housing and Construction, the Ministry of Planning at federal and regional levels, and the Offices of the Land Registries at the Governorate level (PCI 2016b). The Sub-Cluster also engages in advocacy, resource mobilization for land and property interventions, analysis and technical support, restitution and compensation, coordination to mobilize and organize donor interventions, and the development of partnerships with national, regional and local authorities (PCI 2016b). The Sub-Cluster is pursuing a set of seven strategic intervention objectives:

Restoration and provision of civil documentation. The Sub-Cluster is working with the Iraqi government on replacing and producing civil documentation. The lack of this documentation is a primary barrier to exercising land and property rights in a number of areas because such documentation is required for rental agreements, accessing justice and receiving benefits.

The provision of legal aid. The Sub-Cluster works with national and international NGOs and UN partner agencies to provide legal assistance with regard to land and property issues, and supports these efforts to improve the quality and reach of legal assistance.

Shelter-related assistance. For IDPs outside of camps, the Sub-Cluster coordinates humanitarian actors who provide land and property assistance for housing repair and winterization, cash grants to pay rent, and activities to increase tenure security such as ungraded lease agreements and rent control mechanisms (PCI 2016b).

Preventing forced evictions. With efforts focused on areas of the country that are particularly problematic for forced evictions (Baghdad, Kirkuk, Erbil and Dohuk), the Sub-Cluster directs legal services (as opposed to legal assistance noted above) in order to prevent widespread forced evictions. It also develops good practices that can be shared with other organizations and actors engaged in legal aid (PCI 2016b).

Assistance with the planning and implementation of housing policy. The Sub-Cluster assists its various actors and organizations in working with government in the planning and implementation of housing policy for expanding access to adequate and affordable housing and tenure security for IDPs.

Land and property returns. The government is supported in its efforts to re-establish land cadasters where these have been damaged or destroyed, and in transferring land and property records from Baghdad to regional offices. Further support is being provided to government to establish procedures for restitution or other remedies where land cadasters cannot be restored and where land and property disputes overwhelm in-place court systems. As well, support is provided to assist IDPs to secure their land and property rights while still displaced.

Policy for restitution and compensation. The Sub-Cluster and its members intend to work with government for the development of a policy framework for land and property restitution and other remedies, including working with IDP communities regarding their expectations, needs and proposals (PCI 2016b).

Freshwater

RESOURCE QUANTITY, QUALITY, USE AND DISTRIBUTION

The two major water sources in Iraq, the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, provide over 98 percent of the country’s surface freshwater (Abd-El-Mooty et al 2016). The headwaters of both rivers reside outside of the country, and once they enter Iraq the Euphrates traverses approximately 1000 km and the Tigris about 1300 km before joining together to form the Shatt Al-Arab waterway in the southeast of the country which then travels 193 km and drains into the Persian Gulf (Figure 1). Additional tributaries join the Shatt Al-Arab, the most important of which are the Karkheh and the Karen rivers. While the country had ample water supplies compared to its neighbors up until the 1970s, both Syria and Turkey began to construct dams on their portions of the Euphrates during this period, resulting in a pronounced decrease in both quantity and quality of river flow into Iraq (Abd- El-Mooty et al 2016) (Figure 1). While a number of dams on both rivers exist within Iraq, hydropower output in Iraq has dropped in recent years and is often at 30-50 percent of capacity. Together both rivers provide an annual flow of 80 – 84.2 Billion Cubic Meters (BCM), with 65.7 BCM coming from Turkey, 11.2 BCM from Iran, 6.8 BCM from Iraq, and 0.5 BCM added in Syria as the Euphrates passes through—highlighting the very significant influence of Turkey on the flows of both rivers in Iraq (Abd-El- Mooty et al 2016).

The two major water sources in Iraq, the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, provide over 98 percent of the country’s surface freshwater (Abd-El-Mooty et al 2016). The headwaters of both rivers reside outside of the country, and once they enter Iraq the Euphrates traverses approximately 1000 km and the Tigris about 1300 km before joining together to form the Shatt Al-Arab waterway in the southeast of the country which then travels 193 km and drains into the Persian Gulf (Figure 1). Additional tributaries join the Shatt Al-Arab, the most important of which are the Karkheh and the Karen rivers. While the country had ample water supplies compared to its neighbors up until the 1970s, both Syria and Turkey began to construct dams on their portions of the Euphrates during this period, resulting in a pronounced decrease in both quantity and quality of river flow into Iraq (Abd- El-Mooty et al 2016) (Figure 1). While a number of dams on both rivers exist within Iraq, hydropower output in Iraq has dropped in recent years and is often at 30-50 percent of capacity. Together both rivers provide an annual flow of 80 – 84.2 Billion Cubic Meters (BCM), with 65.7 BCM coming from Turkey, 11.2 BCM from Iran, 6.8 BCM from Iraq, and 0.5 BCM added in Syria as the Euphrates passes through—highlighting the very significant influence of Turkey on the flows of both rivers in Iraq (Abd-El- Mooty et al 2016).

Agriculture use accounts for 90 percent of Iraq’s freshwater use. However, salinization of agricultural lands, particularly over the past decades, has reduced yields and produced high levels of salinity in rivers, which then creates problems for the drinking water supply and the restoration of the southern marshlands that were drained by Saddam Hussein (Lorenz and Erickson 2013).

Groundwater usage in Iraq is low, ranging between one and nine percent of all freshwater use, and accounting for approximately 1.2 BCM/year. However, groundwater use is an essential resource in the desert areas, which cover some 58 percent of the country (Lorenz and Erickson 2013). Groundwater quality in the east and north is adequate for drinking and irrigation, whereas groundwater quality is considerably lower in the south and west of the country. In the latter regions, groundwater development has become impossible in some areas and in others where the quality is acceptable, excessive pumping allows for saline water intrusion (Lorenz and Erickson 2013).

In the 1980s a large number of wells were drilled to provide water for agriculture. By 1990 the total number of wells drilled by government reached 8,752, with 1,200 of these being used for agriculture. In addition to these, the private sector established approximately 400 wells in the same timeframe. After the war between Iraq and Kuwait in 1990, no records as to the number of wells excavated were available. It is thought that a large number of additional wells were established during the 1990s when the government pushed the private sector to increase agricultural productivity in response to UN sanctions (Abd-El-Mooty et al 2016).

Iraq’s southern marshlands once constituted the largest marsh system in the Middle East. In 1970 the marshlands covered an estimated 15,000 – 20,000 km2. By the year 2000 this had been reduced to an area of approximately 1,000 km2, comprising between five and seven percent of its original area, due primarily to efforts of the Saddam Hussein regime to drain the marshes in punitive measures aimed at the marsh Arabs (Lorenz and Erickson 2013). There have been a number of efforts to reclaim the marshlands over the past decade with modest success. It has been estimated that it would take approximately 20 BCM of water per year to restore the marshes, which is unlikely to be available given current water demands and declining water availability (Lorenz and Erickson 2013).

LEGAL FRAMEWORK

There is no Tigris-Euphrates basin-wide legal agreement between the countries with an interest in the basin. Lorenz and Erickson (2013) note that despite many years of water resource development, water law plays only a minor role in Iraq and in managing water with other countries in the larger basin. Part of the reason for this is the lack of datasets on water in all the basin countries (Lorenz and Erickson 2013). In Iraq, planning and allocation decisions for water use are managed from Baghdad, and there is little cooperation among the different government agencies that deliver water and almost no water user involvement (Shawky 2008). The primary water laws in the country include:

Ministry of Water Resources Law No. 50 of 2008. This law established the Ministry of Water Resources and created the legal and technical framework for the institutionalization of the management of water resources throughout the country.

Instructions No. 1 on digging water wells. This set of 14 articles regulates well drilling. It establishes that groundwater is state property and hence its exploitation, including extraction, can only occur with a license issued by the General Authority for Groundwater within the Ministry of Water Resources.

Law No 11 of 2012 – Fourth Amendment of Law No. 12 of 1995 Relative to the Maintenance of Networks of Irrigation and Drainage. The primary objective of this Amendment is to give control of the distribution of inland waters to associations connected to specific users. Such associations are established by the users of a common source of water. Associations must work to: raise the efficiency of water use and reduce waste; arrange for a fair distribution of water among participants in the association; contribute to dispute resolution; and maintain irrigation and drainage facilities.

Forests and Woodlands Law No. 30 of 2009. The intent of this law is to prevent deforestation in order to protect waterways and springs. See additional description under ‘Trees and Forests’ below.

Irrigation Law No. 6 of 1962. This law aims to regulate irrigation activities and to protect water resources. It stipulates that the responsible authority for public irrigation activities is the Ministry of Agriculture. The law also states that the Ministry of Agriculture has the responsibility to monitor and protect lakes, rivers and man-made waterways. The Ministry is also responsible for the establishment of irrigation water quotas, water distribution, and supervision of sector activities.

Law No. 2 of 2001 on Preservation of Water Resources. This law regulates the use of water for purposes other than for domestic use. The law establishes rules of water management, use, preservation and pollution.

Law No. 27 of 2009 on the Protection and Improvement of the Environment. This law intends to improve and protect the environment, including the protection of water bodies from pollution by dealing with damaged resources. The Law creates a Council for the Protection and Improvement of the Environment. It is located within the Ministry of the Environment to operate in cooperation with other ministries. The Law stipulates environmental impact assessments shall be completed for new projects within the country.

TENURE ISSUES

Ownership of surface water that crosses international boundaries is a contentious issue in the region and quite political. Iraq and the surrounding states regard release of water data to be a state secret, which undermines effective cooperation regarding water use and quantity of flow across borders and complicates ownership issues (Lorenz and Erickson 2013).

Water rights in Iraq are held by the state. For irrigation purposes users have no water rights per se, and must contribute by the way of fees to the agricultural program set by the government (World Bank 2006). Distribution rights for inland waters can be held by associations of users of a common water source.

In spite of a number of well-intentioned laws regarding use and management, in areas of the country where enforcement and government support are lacking, local-level assertions of rights over water exist, based on the authority of customary institutions. There is no evidence of coordination between such institutions and government.

GOVERNMENT ADMINISTRATION AND INSTITUTIONS

Iraq’s water administration is heavily centralized, and this is reflected in the current laws and administrative structure that govern water use, ownership and management. The Ministry of Water Resources (MoWR) is responsible for water management in the country, including maintenance of the irrigation dams and canals. It is also tasked with promoting and improving water resources, preserving the rights of Iraq in the transboundary water sector, and restoring the southern marshlands in cooperation with the Ministry of the Environment (UNESCO 2014). The MoWR has ‘surveillance staff’ and cooperatives which oversee water management. The Ministry is the successor to the former Ministry of Irrigation, and is organized into a series of commissions, directorates and centers, and is receiving donor assistance to enhance capacity.

Rights to groundwater are also held by the state, and individual users must apply for a license from the General Authority for Groundwater. The National Groundwater Centre, as part of the Commission for Integrated Water Resources Management, works in quantitative and qualitative assessment of groundwater and for developing the national hydrological database. The MoWR has divided the country into 10 groundwater blocks and carries out hydrogeological surveys to determine their potential. The surveys for the desert blocks are complete, and there exists the prospect of establishing additional wells in certain aquifers (Abd-El-Mooty et al 2016; World Bank 2006).

UNDP and UNESCO have assisted Iraq in establishing a series of Local Water Committees in some parts of the country. And while other donors have also worked with the MoWR to establish additional administrative and institutional structures for water management, the Ministry is still in a period of change as is its relationship with other institutions in and out of government and has failed to set up a National Water Management Council (UNDP-UNESCO 2014).

GOVERNMENT REFORMS, INTERVENTIONS AND INVESTMENTS

As noted above the MoWR is still in a period of change, and while it does have a strategic plan, progress in reconstruction and development efforts is behind schedule (Lorenz and Erickson 2013). While the government has plans to build more dams, an uncoordinated operation of these dams could dramatically reduce flows to the marshlands (Jones et al 2008; Lorenz and Erickson 2013). In July of 2003 MoWR put together a one-year plan that included an ambitious schedule for 1) the privatization of certain water facilities, 2) conducting an inventory of all pumping stations and waterworks, 3) the re-establishment of user fees for water, and 4) an emergency repair plan for facilities (Lorenz and Erickson 2013). To date, however, work on these goals is still underway. In 2011, the Iraqi Ministry of Water Resources announced plans to build a 129 km canal to divert water from the Shatt Al-Arab waterway for use in irrigation, bringing approximately 0.95 BCM/year to agricultural land in Basra Governorate (Abd-El- Mooty et al 2016).

DONOR INTERVENTIONS AND INVESTMENTS

Water infrastructure reconstruction began under the Coalition Provisional Authority and continued after the transfer of sovereignty at the end of June 2004. In 2003 the US approved $4.3 billion for water and public works (re)construction, including 90 large water projects. By 2004 however ongoing insecurity prevented meaningful progress in water infrastructure reconstruction. Security costs and administrative costs for Western companies further decreased the funds available for actual reconstruction and created obstacles and delays, with the result being that contractors were only able to supply half of the potable water that was initially planned (Lorenz and Erickson 2013).

Also in 2003, the US worked with the Ministry of Water Resources in the preparation of a new Water Resources Master Plan, but it was not completed. In 2011 the Italian government provided funding for a similar effort through the Department of Agricultural and Forest Engineering at Florence University in Italy. The Italian project includes assistance with the recovery of the southern Iraqi marshlands, and the establishment of monitoring stations located throughout the country including on both the Tigris and Euphrates rivers. Information on the progress of this effort, however, is scant.

Trees and Forests

RESOURCE QUANTITY, QUALITY, USE AND DISTRIBUTION

The forest area in Iraq is minimal. Approximately 822,000 ha, or 1.9 percent of the country, is in forest cover, with all of it classified as subtropical. Of this, none is in primary forest, with 98.4 percent of the forested area existing as ‘modified natural’ forest (containing 20 native species) and the remaining 1.6 percent in tree plantations (Butler 2005). Between 1990 and 2000, forest cover increased by an average of 1,400 ha/year, comprising an average annual reforestation rate of 0.17 percent/year. However, between 2000 and 2005 the reforestation rate had decreased to 0.1 percent/yr. Overall between 1990 and 2005 the country gained approximately 2.2 percent of its forest cover—about 18,000 ha. Forest lands are protected in Iraq, with approximately 80 percent existing under some form of protected status, and the remaining 20 percent in some form of conservation (Butler 2005).

As of 2002, when the last reliable estimates were available, wood fuel use stood at 43,000 m3, all of which is consumed domestically. Forest production for lumber was 12,000 cubic m, which when combined with an import of 16,000 m3 results in 28,000 m3 of lumber consumption. Forest pulp production for paper was 11,000 metric tons in 2002, all of which was consumed domestically. Forest for paper and paperboard production was 20,000 metric tons, which together with an additional 20,000 metric tons imported, put paper and paperboard consumption at 40,000 metric tons (Butler 2005).

LEGAL FRAMEWORK

There are three primary laws in Iraq that govern the ownership and use of forests and forest lands.

Forests and Woodlands Law No 30 of 2009. Comprised of four sections and 27 articles, this law seeks to prevent deforestation primarily for the purpose of protecting waterways and springs. The primary objectives of the law are to: organize the protection, management, maintenance and improvement of forests; increase the area under forests; combat erosion and desertification; encourage agricultural investment; preserve the agricultural heritage of Iraq; and provide recreation and job opportunities.

Notification No. 5 of 1967. This regulation seeks to prohibit tree cutting, charcoal making, and the transport of forest products for commercial purposes in certain natural forest areas. Exceptions to these prohibitions are listed in Article 2 of the Notification. The regulation stipulates that villagers may cut trees and transport wood products for specific purposes within forest regions.

Forestry Law No. 10 of 2012 of Iraqi Kurdistan Region. Pertinent only to the Kurdistan Autonomous Region (where most of the forest lands in the country are located), this law seeks to: 1) organize the protection, management, maintenance and improvement of forest lands; 2) increase the area of green space; 3) protect the environment; 4) mitigate the effects from climate change; 5) encourage agricultural investment in forestry; 6) provide raw materials needed by the wood industry; 7) preserve varieties of naturally occurring tree species and maintain their genetic origins; and 8) provide for recreational and tourist areas.

TENURE TYPES AND SECURITY

While all forest land is classified as ‘public land’ (Butler 2005), the Forests and Woodlands Law stipulates that this does not apply to trees on gardens and parks within cities and towns, private gardens, and trees and shrubs of cemeteries and holy shrines, as well as all kinds of trees and shrubs on privately held lands. The law does however specify that trees held on private lands may not be cut except for necessity, particularly if the trees concerned are involved in waterway protection or the protection of springs. In addition, certain actions are banned without the prior approval of the General Company for Horticulture and Forestry. Thus, while actual ownership of trees on privately held land appears secure, what a private owner can do with trees is significantly controlled. Trees on land held commonly by lineages or tribes is not mentioned in the law, but it is in Notification No. 5 of 1967 where it is noted that villagers can cut wood and transport wood products for certain purposes only.

GOVERNMENT ADMINISTRATION AND INSTITUTIONS

The government administration for forest lands resides within the General Company for Horticulture and Forestry, within the Ministry of Agriculture.

GOVERNMENT AND DONOR REFORMS, INTERVENTIONS AND INVESTMENTS

The National Environmental Strategy and Action Plan for Iraq (2013-2017) mentions intervention in the country’s deteriorating forests and woodlands only briefly, noting that the problem will be addressed by “implementing projects to develop and rehabilitate forests, woodlands and orchards” (RoI 2013). The government does however support outside investment in the forestry sector, with the Iraq Investment Map (2017) noting the opportunity in this regard for the ‘agriculture, forests and hunting’, tourism, and date palm sectors (RoI 2017).

The date palm sector is the focus of some attention in Iraq for the government, certain donors and the inhabitants of specific areas. The government, beginning in 2005, initiated a recovery plan for date palm focused on replanting programs. The Date Palm Department within the Ministry of Agriculture is involved in a $150 million investment to triple the number of date palm trees in the country by 2021. The government is also courting private investors to cultivate date palm areas in the western desert. Given that date palm trees numbered 32 million in the mid-20th century, then dropped to 12 million by 2000 and then was reduced further in subsequent years due to conflict and embargo; and that Iraqi cultivated dates were seen as among the best in the Middle East, the investment potential would seem to be significant. Donor interest in Iraq’s other forestry sectors is minimal, and is usually combined with the recovery and conservation of natural resources.

Minerals

RESOURCE QUANTITY, QUALITY, USE AND DISTRIBUTION

Hydrocarbons. Iraq’s mineral wealth is substantial, particularly with regard to oil and gas. Iraq produces approximately 4.2 million barrels of oil per day, making the country the second largest producer in OPEC, an organization it helped establish. Natural gas production on the other hand remains low, particularly compared to proven reserves. Most natural gas produced in the country is currently flared, but there are plans to capture flared gas and market it. The country is 12th in the world in terms of proven natural gas reserves with 111.52 trillion cubic feet, and gas reserves are expected to grow significantly with continuing exploration. Overall Iraq is ranked as third in the world for reserves of oil and natural gas (Failat 2011).

Iraq exports about 3.48 million barrels per day of crude oil, most of which is produced in Basra. In 2012 Iraq was the sixth largest net exporter of petroleum liquids in the world, and its proven crude oil reserves of 141.5 billion barrels are the fifth largest in the world, representing almost nine percent of global proven reserves (Deven and Al-Amin 2014). Most of the country’s proven oil reserves reside in the southern part of the country, but some exploration is in the north between the Kurdistan Region and the Iraqi provinces Ninewa, Kirkuk, and Diyala.

Solid minerals. Government released estimates for the country’s proven solid mineral resources include 10 billion metric tons (MT) of phosphorite, 8 billion MT of limestone, 1.2 billion MT of kaolinite clay stones, 600 MT of antic sulfur, 330 MT of dolomite, 130 MT of gypsum, 75 MT of quartz sand, 22 MT of both glauberite and bentonite, 50 MT of Halite salt, 16 MT of quartzite, and 2.3 MT of feldspathic sandstones, in addition to significant reserves of construction sand, sandstone and gravel (Taib 2011). The northern and northeastern parts of the country contain a belt of minerals in smaller quantities that include chromium, copper, gold, iron, lead, manganese and zinc (Abdulameer 2014).

LEGAL FRAMEWORK

Hydrocarbons. While Article 112 of the Constitution stipulates the enactment of a law to regulate oil and gas, as of 2017 this has not occurred. And no updated information is available at the time of writing. A proposed law has stalled amidst disagreement and political division since a draft was submitted in 2011 (following an earlier draft of 2007). The proposed federal oil law of 2011 has drawn criticism from different quarters in Iraq, hindering its passage. The Sunnis prefer a stronger role of central government, while the Kurds prefer a stronger role for regional authorities. The role of foreign investors (such as BP, Exxon and Total active in the south), as well as the classification of oil fields, also divides politicians (Beehner and Bruno 2008).

The different sources of regulations and laws that comprise the regulatory regime in Iraq produce a degree of uncertainty regarding the hydrocarbon sector. Confusion regarding which laws and regulations apply in any given situation or for different actors, stems largely from changes in the political system over time. Thus, certain laws that pertain to oil and gas which were enacted during the Kingdom era, the military and Ba’athist regimes, and issued by the Coalition Provisional Authority remain in effect (Blanchard 2009; Devine and Al-Amin 2014). This is the case because article 130 of the Constitution states that pre-existing laws remain in effect unless they have been specifically repealed or amended. The result is that some older laws that do not fit with the current legal environment still apply and are often enforced (Blanchard 2009). The overall result is that the regulatory regime that applies to gas and oil exploration and production is based primarily on the laws and regulations produced by the Ba’athist government prior to 2003. It should be noted that nationalization of the oil and gas sector started in 1960 before the Ba’athist coup in 1968. Foreign companies were limited to certain areas around Kirkuk and Basrah until 1972 when the oil and gas sector was fully nationalized. The Iraq National Oil Company (INOC) was created in 1964 to take over from foreign oil companies. INOC was subsumed under the Ministry of Oil in the late 1980s.

The legislation applicable in Federal Iraq includes:

- The Organization of Ministry of Oil Law of 1976;

- The Preservation of Hydrocarbon Resources Law No. 84 of 1985;

- The Ministry of Oil Regulation Law No. 21 of 1978;

- The Iraqi Revolutionary Command Council Order No. 1075 of 1976 regarding authority to negotiate and sign petroleum contracts;

- Revolutionary Command Council Order No. 167 of 1985 regarding oil pipelines;

- Protection of the Environment Law No. 27 of 2009, which stipulates that an Environmental Impact Statement (EIA) must be submitted by a hydrocarbon ‘project owner’.

The Ministry of Oil has wide discretionary powers in the management of hydrocarbons, and has invited foreign companies to work in Iraq by way of four petroleum licensing rounds. The majority of licenses were issued in the first and second round. In the Iraq Kurdistan Region the Regional Government has enacted its own oil and gas law, the Kurdistan Oil and Gas Law No 28 of 2007. Following passage of this law, the Kurdistan government has moved to award numerous contracts to oil companies, but the federal government does not view these contracts as legal.

Solid Minerals. Investment Law No. 13 of 2006 covers areas of investment for solid minerals, as well as other sectors, excluding hydrocarbons (Taib 2011). The Iraqi Ministry of Industry and Minerals Law No. 38 of 2011, defines the objectives, scope and structure of the Ministry (Abdulameer 2014).

TENURE TYPES AND SECURITY

According to the Constitution oil rights are held by the people of Iraq; hence rights to oil and gas are not generally held by those who may hold surface rights to land. The result is that the state of Iraq, acting through the government, is the sole representative of the Iraqi people, and thus has exclusive rights to: explore, develop, extract, exploit and use hydrocarbons in the county, including the appointment of contractors to assist carrying out these activities (Blanchard 2009).

The Kurdistan Regional Government, however, takes the position that the provinces and Federal Regions have the rights to explore, develop, exploit and use hydrocarbons that exist within their territory without the need to consult the Federal Government (Blanchard 2009; Devine and Al-Amin 2014). It is expected, however, that once the proposed Federal Oil and Gas Law is enacted, it will clarify who has what rights to oil and gas and how these rights can be used. This is likely to be a difficult topic to resolve between the Kurdish government and the federal government given the current (late 2017) difficult relationship between the two.

GOVERNMENT ADMINISTRATION AND INSTITUTIONS