This article was originally published on the Next Billion website.

By: Mary Hobbs, Director for the Agriculture, Environment, and Business Office, USAID/Mozambique

Mozambican farmer Lucia Maurício farms about 10 hectares (25 acres) of land to feed her five growing children.

Portucel Executive Director Paulo Silva manages more than 13,000 hectares (32,000 acres) of eucalyptus farms in Mozambique to feed a growing multi-million-dollar global supply chain hungry for paper pulp.

They have more in common than you might think.

Both require the same foundation to achieve their goals: clear and documented land rights.

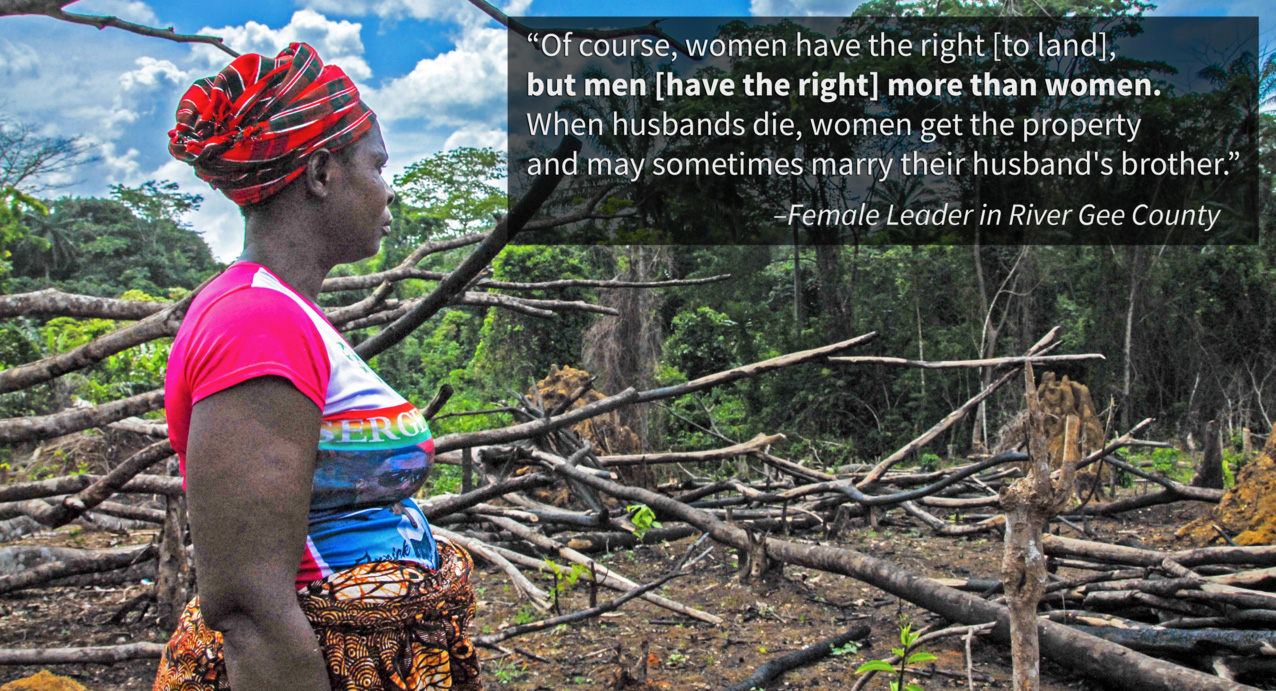

Just as clear and documented land rights allow farmers to invest in their land to improve their harvests and their lives, they allow investors and corporations to more easily identify farmers and communities with surplus land, and to negotiate to access or lease the land they need to keep their company running.

Land rights are an underappreciated precondition across the agriculture spectrum – from the largest agriculture companies to subsistence farmers, their foundation for success is documented and secure land tenure.

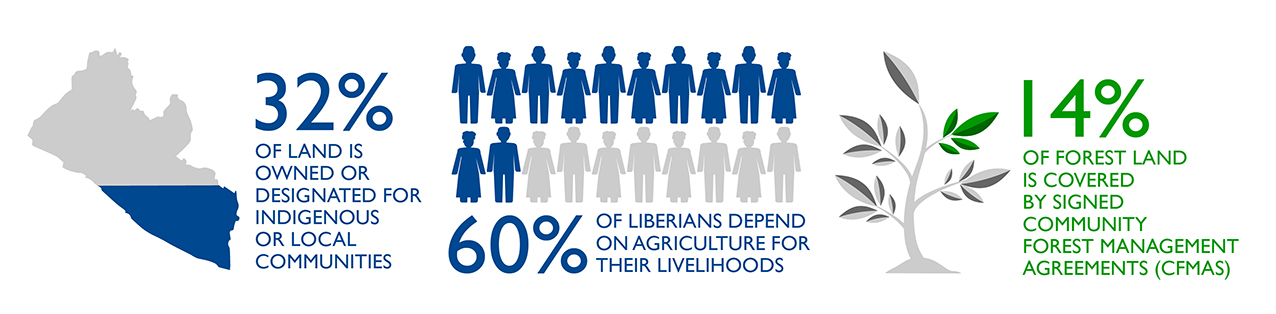

This may sound like a simple requirement, but in Mozambique and many other sub-Saharan African countries, that foundation had not yet been laid. According to the World Bank, only 10% of agricultural land in sub-Saharan Africa is documented. In Mozambique, where Lucia farms and Paulo works, the FAO says only about 20% of land is documented. Those figures haven’t changed much in decades – trapping farmers like Lucia in poverty and providing hurdles to investment for investors like Paulo.

Most farmers in Lucia’s village of Enhumua farmed without titles or deeds to the land they rely on. They farmed land passed down to them or bought on a handshake. The contours and boundaries of each parcel were rarely noted on paper.

And when land tenure is unclear or undocumented, both farmers and businesses suffer.

This was the case for Lucia. Previously she could not capitalize on the most fertile section of her land because of conflicting claims. The parcel was by the river, well irrigated, and blessed with rich, productive soil. But her neighbors also claimed the land. And this threat influenced the way she farmed. Instead of trying to maximize profits, she and her husband Calisto tried to minimize their risks. Despite the land’s potential, she planted only corn on the parcel. She feared that if she planted other vegetables, which are much more profitable, her neighbors would take the investment as an irresistible invitation and seize some or all of her crop along with her land.

This type of conflict over land has long been common, and it intensified in 2010, when the government granted approximately 173,000 hectares of land in Zambézia province (which includes Lucia’s village of Enhumua) to Portucel-Mozambique to establish large-scale eucalyptus farms. Zambézia is the second most populous province in Mozambique. So across Zambézia, villages like Enhumua do not have a lot of vacant and unused land.

Portucel staff immediately recognized the challenges of operating a business in such an uncertain environment when they began negotiating with villagers to lease land. In Namalapa village, not far from Enhumua, Joao Ernesto Prego received an unwanted surprise when Portucel claimed rights to 3.5 hectares of his land. Joao’s nephew had signed over rights in exchange for a promise of lifetime employment with Portucel. Portucel had a signed document from the nephew, and Joao found he had little recourse.

As the company’s eucalyptus farms sprouted across the horizon, similar stories – born of a tangled web of unclear and undocumented land tenure – multiplied. Eventually, as with many companies, Portucel ceased all land procurement negotiations and put future investments on hold while they worked out how to responsibly negotiate with and invest in communities where land tenure is undocumented and unclear. Land disputes can very easily escalate, creating tensions in a community that make it unsafe for families and businesses alike.

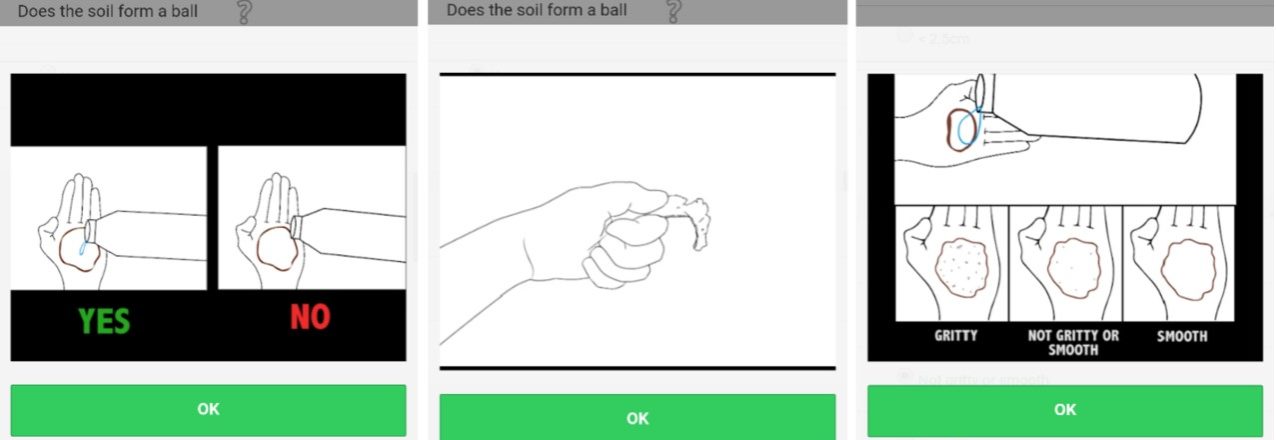

The company’s hopes for the future, along with those of Lucia and other farmers, soared when USAID and DFID-funded programs to document smallholders’ land rights came to the region. The programs trained farmers like Lucia to document land boundaries with GPS technology.

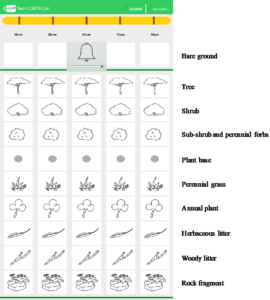

Farmers walk the boundaries of their land, GPS in hand and witnesses in tow, to map their properties. Each farmer is provided with a certificate signed by local leaders that includes a satellite map of the farm, GPS coordinates, the farmers’ names, and the names of community leaders and witnesses.

The certificates provide smallholders like Lucia and Calisto with their first documentation of their land rights. This added security has been transformative for Lucia, her community and Portucel. When farmers like Lucia have secure rights to property, they can negotiate with businesses to loan or lease their land, or arrange an out-grower contract with a company like Portucel and enter the global marketplace.

With clearly documented land boundaries, Portucel can finally identify landowners with surplus land and negotiate to access or lease it. They can also identify vacant parcels and pursue options for leasing that land from the government or communities.

Portucel hopes these changes will enable it to reduce its investment risk and increase the sustainability of its business. As Paulo Silva says, “Now, in a vast area of our holdings, we all know the right locations of the plots of people living there, creating better conditions for dialogue between the company, communities and individuals. This allows us to better plan for the future.”

Lucia certainly wasted no time in taking advantage of her newfound confidence in her land rights. She is planting a vegetable garden on her prized parcel and, with the proceeds from that harvest, will gain a measure of self-reliance heretofore unimaginable. She and her husband expect the vegetable plot will quadruple their income. Such a jump in their earnings would finally allow them to put a much-needed zinc roof on their home, support their children’s education, and improve the productivity of their other fields with investments like fertilizer or better-quality seeds.

“We can farm as we please,” says Lucia with a smile. “Life is good now.”

Martins Gabriel Paiva, a village chief often called upon to settle land disputes, has also noted the change brought by better documentation of land rights. “In the past there was constant conflict over land,” he says. “Now there is harmony.”

Martins notes that Lucia’s story is being replicated across the district. “The land thieves now know that every parcel has an owner,” he says. “We are now kinder to each other. We have a community group that has the people’s trust and it is working on building a community fishpond.”

“Now,” he adds, “we can improve our development.”

Mary Hobbs is the Director for the Agriculture, Environment, and Business Office at USAID/Mozambique.

Photos courtesy of Mary Hobbs – USAID.

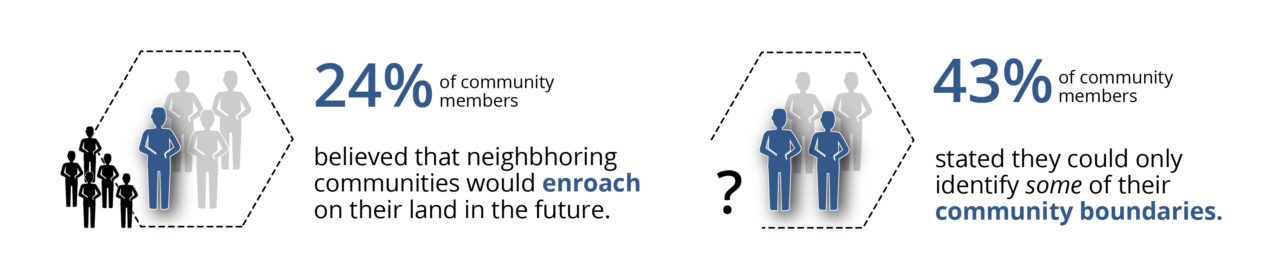

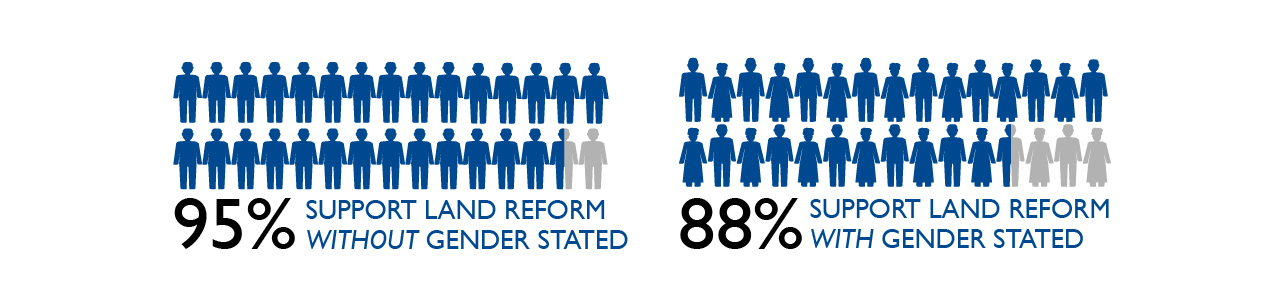

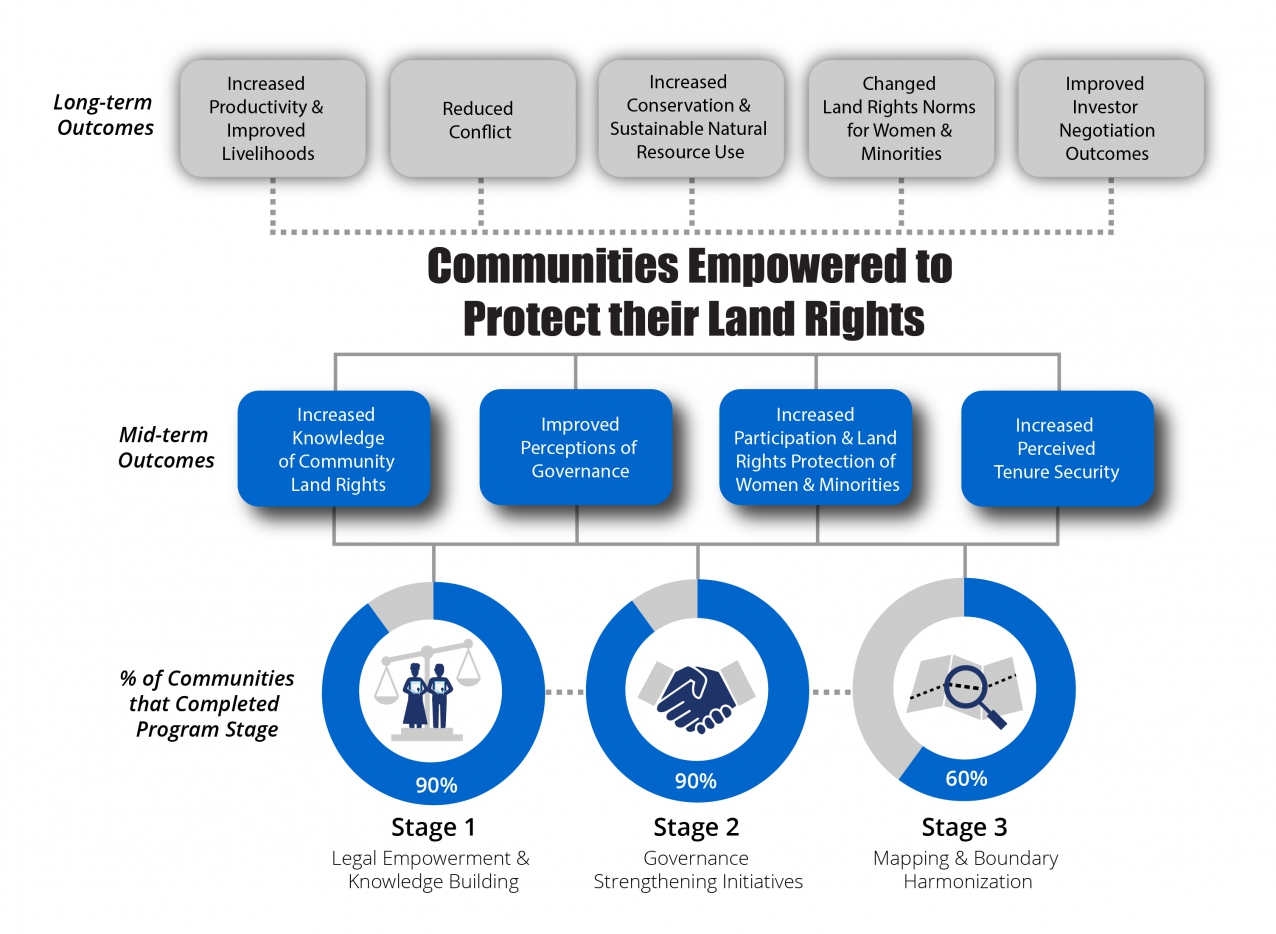

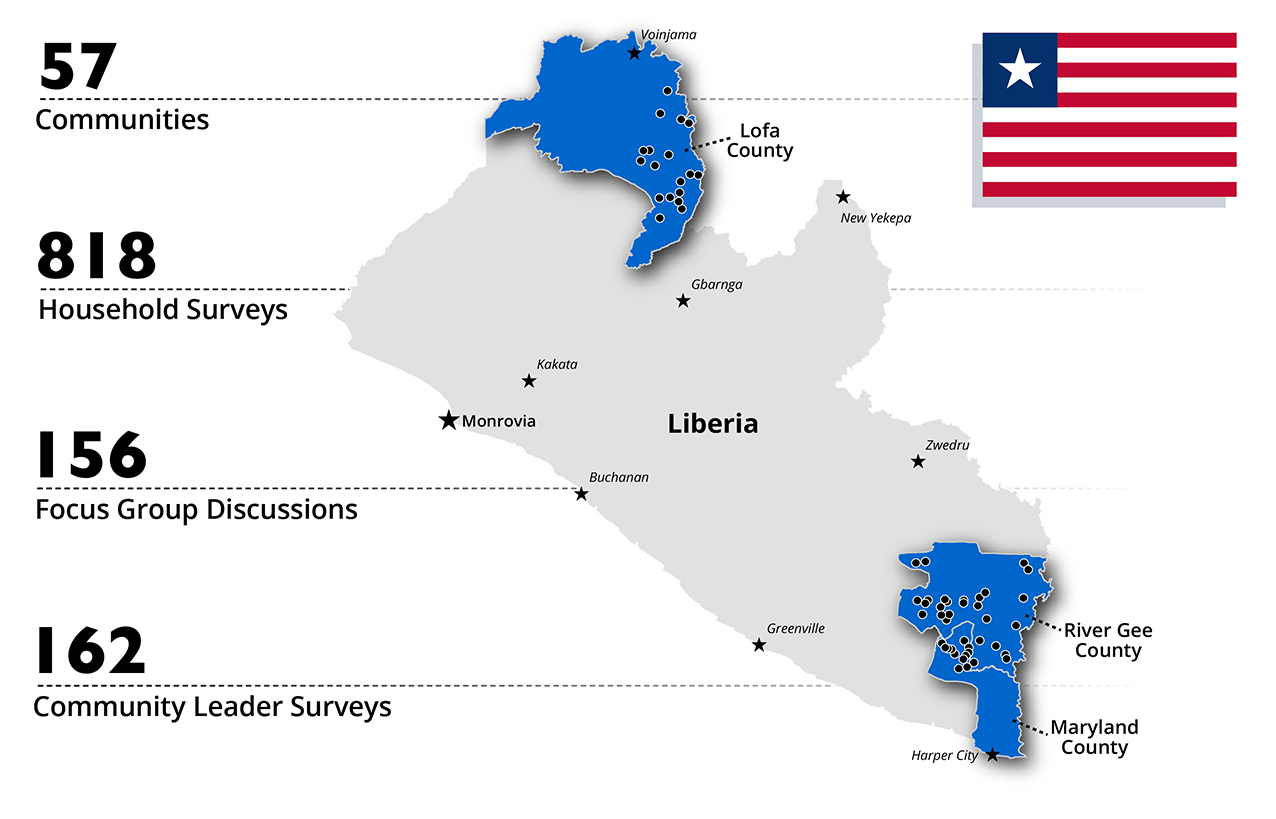

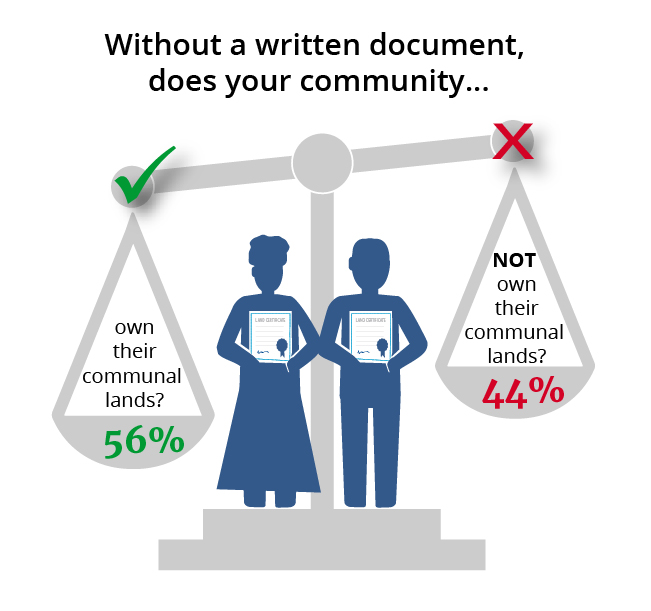

Baseline results indicated that respondents were divided on their knowledge of community property rights. Forty-four percent incorrectly stated that without a written document, the community did NOT own their communal lands.

Baseline results indicated that respondents were divided on their knowledge of community property rights. Forty-four percent incorrectly stated that without a written document, the community did NOT own their communal lands.