USAID is helping the government to increase efficiencies around rural land administration and reduce the cost and time to title rural property in Colombia.

One early morning in 1994, Gloria Ester Buelvas was woken and told she had to leave her grandfather’s farm in San Pedro de Urabá, where she had lived 16 years of her life. Nearly three decades later, Buelvas still does not know why she and dozens of members of her family were threatened and forced to leave their hometown.

One early morning in 1994, Gloria Ester Buelvas was woken and told she had to leave her grandfather’s farm in San Pedro de Urabá, where she had lived 16 years of her life. Nearly three decades later, Buelvas still does not know why she and dozens of members of her family were threatened and forced to leave their hometown.

“The paramilitaries told us we had from dusk to dawn to leave town. We organized ourselves and went to Carepa, 100 kilometers away,” Buelvas said, recounting a traumatic experience. “But when we got there, they told us that we had to leave from there too.”

Colombia’s Urabá region stretches from the border of Panama along the Caribbean coast and is famous for bananas and large cattle ranching estates. Over generations, the region became a textbook example of the type of class divisions between landless farmers and an elite land-owning class that fomented strife and erupted in brazen warfare between the leftist guerrillas and paramilitary groups in the nineties. Families like the Buelvas were caught in the middle, accused of helping or supporting one side or the other.

Colombia’s Urabá region stretches from the border of Panama along the Caribbean coast and is famous for bananas and large cattle ranching estates. Over generations, the region became a textbook example of the type of class divisions between landless farmers and an elite land-owning class that fomented strife and erupted in brazen warfare between the leftist guerrillas and paramilitary groups in the nineties. Families like the Buelvas were caught in the middle, accused of helping or supporting one side or the other.

Although the traumatic memory of displacement persists, Gloria Buelvas and her family eventually found peace 500 kilometers away in Meta, a corner of Colombia’s eastern plains. La Unión del Ariari is located in the municipality of Puerto Lleras and home to a hodgepodge of families displaced by decades of conflict and several Venezuelan families who recently arrived.

Lack of Access

Over the years, the municipality provided relief, including improved roads and electricity, and the families rebuilt their lives. Gloria and her neighbors supported each other through subsistence agriculture, but none have ever obtained a land title for their property. In Colombia, low-income families can rarely afford to access land formalization services, which are complicated and expensive. In fact, the majority of Colombia’s rural parcels lack a registered land title.

Over the years, the municipality provided relief, including improved roads and electricity, and the families rebuilt their lives. Gloria and her neighbors supported each other through subsistence agriculture, but none have ever obtained a land title for their property. In Colombia, low-income families can rarely afford to access land formalization services, which are complicated and expensive. In fact, the majority of Colombia’s rural parcels lack a registered land title.

Families without registered land titles mean the country’s cadaster, which is a comprehensive map of land ownership, is severely out of date, especially in areas that have been affected by violence. Unclear land rights with no backing from the state have made it easy for illegal groups to run off people like Gloria Buelvas from their land.

This is changing, thanks to the implementation of Rural Property and Land Administration Plans, or POSPRs by their Spanish acronym, all over the country. USAID is helping the Government of Colombia untangle land administration issues and meet its commitments to the 2016 Peace Accords. The Land for Prosperity Activity is USAID’s largest investment in land tenure programming in the world and its main objectives are updating the rural cadaster and strengthening land administration.

Updating Records

When the cadaster of Puerto Lleras was last updated in 2011, it included 2,300 properties. Following the implementation of the 2023 POSPR, the initiative surveyed over 4,600 properties, many of which are home to displaced families. More than half of these parcels are not recognized by the state but are ready to be formalized and issued a registered land title.

When the cadaster of Puerto Lleras was last updated in 2011, it included 2,300 properties. Following the implementation of the 2023 POSPR, the initiative surveyed over 4,600 properties, many of which are home to displaced families. More than half of these parcels are not recognized by the state but are ready to be formalized and issued a registered land title.

In addition to formalizing properties, the Rural Property and Land Administration Plan provides the government with information about landholdings that could be subject to agrarian reform processes and provides a path for more than 700 landless farmers from Puerto Lleras to apply for land with the government.

“The government is going to give me the deed to my little piece of land, so I named my farm ‘La Bendición’ (The Blessing) because it has been a blessing for me and my family.” says Gloria Ester Buelvas.

Reaching Complex Municipalities

Puerto Lleras is one of 11 municipal-wide Rural Property and Land Administration Plans being supported by USAID. After considerable preparation and training, the implementation of POSPR requires an average of 18 months to complete field work and information gathering. Once completed, it is up to Colombia’s National Land Agency to deliver property titles to landowners.

Puerto Lleras is one of 11 municipal-wide Rural Property and Land Administration Plans being supported by USAID. After considerable preparation and training, the implementation of POSPR requires an average of 18 months to complete field work and information gathering. Once completed, it is up to Colombia’s National Land Agency to deliver property titles to landowners.

With government support, USAID is implementing POSPR in some of Colombia’s most complex regions, where armed groups operate and illicit crops play a role in the local economy.

The POSPR methodology, which has evolved since being first tested in 2018, uses a variety of approaches to reach rural landowners. After a thorough analysis of available property records, squads of technical, legal, and social experts sweep the countryside, engaging communities, documenting parcels, and updating landowner information in the cadaster. A social outreach component relies on the support of volunteer community leaders and is critical in reaching rural residents with information about the land titling process, formal land markets, and women’s land rights.

“People around here ask why the state wants to give them land titles. There is a fear that if the government gives you a land title, it will then take away your land,” explains Luz Estela Velandia, who worked as a community volunteer for the POSPR in Fuentedeoro. “We assure them that nobody will come and take away their land. In fact, it is the opposite. A land title ensures they are recognized as owners under the law.”

Calculating Costs

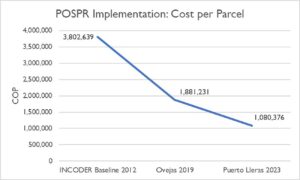

To improve implementation, USAID has created a mathematical model to calculate the direct cost per property of POSPR implementation in municipalities where USAID has completed interventions, including Puerto Lleras. By tallying all costs related to the implementation of the parcel sweeps, including labor, logistics, systems, infrastructure, and more, USAID extrapolated a cost per property as well as cost per property by process, type of parcel, and route of parcel formalization.

Using a baseline from Colombia’s former land administration authority, INCODER, in Puerto Lleras USAID identified a 72% decrease in the cost-per-parcel from COP $3,802,639 to COP $1,080,376. When compared to the results of the first USAID-supported massive parcel sweep in Ovejas, which had already reduced the costs of the baseline, USAID found a 43% decrease (See graph below in Colombian pesos).

This would still be a steep price for first time landowners, however the cost of adjusting property records thereafter is much lower.

Since the Peace Accord was signed in 2016, USAID has been the foremost partner in facilitating the government strategy to move away from a demand-driven land administration policy to one in which the government assumes the cost of first-time formalization. The large-scale POSPR interventions alleviate the burdens that once prevented most low-income rural landholders from seeking a valid title. Once a property is registered, future title transfers become less time and cost intensive.

“I tell people that, yes, they will have to pay property taxes, but a land title can also bring them government subsidies, programs, and better services. I tell them a land title represents their rights. And I tell them that women have the same rights to appear on a property title as a man,” says Velandia.