Overview

In 2015, Nepal was hit by a devastating 7.6 magnitude earthquake which along with its resulting aftershocks slowed economic growth, displaced hundreds of thousands of Nepalese and affected a total of 8 million people. Shortly after, the government of India began restricting the movement of goods and supplies over a disagreement with the new constitution, intensifying the economic and humanitarian crisis. The government of Nepal, with its new constitution, and with its recent transition to a federal system faces many challenges in preserving the peace and delivering development in a context of great geographical, ethnic, and social diversity. The country has abundant water resources, well-distributed forestland, and a relatively concentrated area of cultivable land, but needs to strengthen its weak institutions to sustainably manage its land and natural resources. Nepal’s highly stratified and hierarchical social structure has tended to limit access to resources and economic opportunity. Consequently, Nepal remains a low-income economy, highly dependent upon agriculture, with 25 percent of its 29 million people living below the national poverty line. The poorest are those land-poor families especially women, Dalits, ethnic minorities, economically poor people, and agricultural laborers.

Poverty in Nepal is highly correlated to the size and quality of landholdings. There have been past efforts at land reform, but little success in equalizing highly skewed land holdings, reducing landlessness and improving security of land tenure. These chronic land issues helped to fuel the years of conflict. Natural disasters in the form of frequent floods and landslides (in addition to earthquakes) further exacerbates these problems. The government is in the process of revising the legal and policy and institutional framework governing land in line with the Constitution 2015 and has committed to an agenda of scientific land reform.

Despite Nepal’s wealth of water resources, unequal access to water has caused tension in the country, especially where competing water uses (e.g., irrigation, drinking water, hydropower, and industrial use) vie for access. Nepal’s abundant surface water resources have been harnessed to provide energy but are increasingly polluted by the discharge of untreated human and industrial waste.

Nepal’s forests are a critical source of food, medicine, building materials, and animal fodder. The insurgency disrupted management of, and created conflict over, forest resources by removing government oversight and support, and creating an atmosphere of insecurity and distrust. Much of the forestland between the Himalayas and the lowland plateaus has been cleared for crops, livestock, and human settlement. Timber is being harvested at a rapid rate, and much of the land in Nepal’s hills is degraded. Landslides, erosion, and soil degradation are common. Nepal’s forest land has, however, increased by more than 5 percent in the recent years and the rate of deforestation is slowing.

Key Issues and Intervention Constraints

Nepal faces tremendous vulnerability to conflicts due to its manual record keeping system for land. The Department of Land Information and Archives (DoLIA) has successfully completed the digitization of records and cadastral maps in all of the 129 land revenue and survey offices, except Achhaam and Arghakhanchi. However, only 19 such offices have been able to fully digitize. The rest of the offices continue using traditional methods for new registrations, which means that digital record systems are not updated. The land revenue offices and the survey offices use separate software creating problems sharing information between the two.

Merging the two departments into one would help improve information flows, increase transparency and help the general public. As the state and local government gains more power regarding land, the political tussle preventing such merge could possibly be mitigated. Unfortunately, an integrated digital land information system is not functioning and effective transition to local level land management will be plausible only after full digital integration. Donor organizations could help create an integrated software system. Helping create a research wing for DoLIA could also minimize inefficient procedures. Since much power regarding land administration and implementation of policies has been given to the local government, they will require support for transferring existing information to the new offices as well as for building technical and management capacity of the local officers. State and federal governments will require continued support in formulating strategies for effective land management and progressive policies.

At the policy level, women’s rights to land have been taking a progressive turn. New laws have been drafted to ensure that the legal framework improves and protects the rights of women. However, socio-cultural norms have prevented women, especially those in the rural areas, from benefiting from tax discounts and other incentives that the Government of Nepal (GON) provides for joint/women registration, equal ancestral inheritance and spousal rights. Donors could work with elected women representatives at the local level and with local NGOs to educate people on women’s legal land rights, support advocacy and public awareness campaigns, and extend legal aid services to women, especially in terms of procuring citizenship certificates.

Nepal has seen much success in conserving biodiversity and forests over the past 40 years, however threats such as grazing, encroachment, over exploitation and illegal exploitation of biological resources persist. USAID’s 2012 assessment identified several areas where donors could provide assistance in helping conserve biodiversity and reduce deforestation, support and extend structures for good governance of natural resources, and develop livelihood and economic activities with attention to conservation goals and local community needs. The assessment and its recommendations provide a starting point for donors to engage or reengage in Nepal’s forest sector. Particular areas of need are: (1) strengthening and expanding community-based models of conservation; (2) promoting informed decision making by improving the ability of government and civil society to gather and synthesize information; (3) building capacities of institutions to implement existing and newly drafted policies and (4) adopting frameworks such as a sustainable livelihoods or green economy approach to mainstream environment into their development objectives, and link biodiversity and forestry to other program areas such as economic growth, health and disaster risk reduction. A framework that aims to sustain and advance economic, environmental and social well-being by linking development and economic growth would encourage integrated development plans among different crucial sectors.

Water resources in the Kathmandu Valley are often stressed: during long dry spells wells dry up and drinking water is limited. In addition, climate change is expected to accelerate glacier melt in the Himalayas, increasing flooding and ultimately decreasing river flow and freshwater resources. The government and donors have partnered on projects to create water user groups, provide technical assistance on sustainable water management techniques, and expand irrigation infrastructure. Donors could continue to assist the government in building local governance structures to manage water resources and develop a foundation for community-based integrated natural resource governance institutions that manage resources with recognition of the interconnectedness of water, agricultural land, forests, and rural livelihoods. Additionally, donors should help set and achieve the goals of expanding access to modern, high quality hydropower services for the citizens of Nepal and to realize the potential for Nepal’s hydropower exports in South Asia. Donors could further help with irrigation by building artificial small ponds, especially in the hilly regions as a means of exploring alternative irrigation techniques.

Summary

The devastating 7.6 magnitude earthquake that hit Nepal on April 25, 2015, and its resulting aftershocks killed more than 8,700 people, injured 23,500, destroyed 850,000 houses, displaced more than 117,000 people and affected over 8 million people. Shortly after – during reconstruction and rehabilitation efforts – a new Constitution was passed, marking a transition to federalism. Nepal’s new government system must manage a country rich in geographical, ethnic, and social diversity, with a multitude of opportunities and challenges. Nepal’s geography ranges from the Himalayan Mountains to lowland plateaus with abundant water resources, well-distributed forestland, and a relatively concentrated area of cultivable land. The predominantly Hindu country has a mixture of ethnic groups and a highly stratified and hierarchical social structure, which has controlled access to resources and economic opportunity. Twenty-five percent of the Nepalese population live below the national poverty line. The poorest are those in the lower castes, Muslims, and agricultural laborers. (Oxfam et al. 2016; Basnet 2016)

Land productivity is low due to lack of irrigation, inconsistent use of inputs, and inadequate infrastructure. A high percentage of agricultural land is idle. According to the Department of Agriculture’s annual agriculture diary 2015, only 3,091 hectares of land was cultivated whereas 1,030 hectares of land was left fallow. Twenty-five to twenty-eight percent of agricultural land is left fallow due to various reasons including absentee landlords. Landlords are hesitant to rent out their land for sharecropping out of fear of property claims by tenants. Existing tillers are being evicted on a daily basis. This is testament to weak tenure security of both the landowners and tillers. Although contract farming has started being practiced in some places, a formal act concerning contract farming agreement is not in place. To date, the draft for the Agriculture Enterprises Promotion Act which includes provisions for contract or lease farming has not been finalized. (Pokharel, Shrestha 2016; Jagat Deuja. CSRC. Personal Interview. November 1, 2017; IOM 2016; Acharya 2017)

Land productivity is low due to lack of irrigation, inconsistent use of inputs, and inadequate infrastructure. A high percentage of agricultural land is idle. According to the Department of Agriculture’s annual agriculture diary 2015, only 3,091 hectares of land was cultivated whereas 1,030 hectares of land was left fallow. Twenty-five to twenty-eight percent of agricultural land is left fallow due to various reasons including absentee landlords. Landlords are hesitant to rent out their land for sharecropping out of fear of property claims by tenants. Existing tillers are being evicted on a daily basis. This is testament to weak tenure security of both the landowners and tillers. Although contract farming has started being practiced in some places, a formal act concerning contract farming agreement is not in place. To date, the draft for the Agriculture Enterprises Promotion Act which includes provisions for contract or lease farming has not been finalized. (Pokharel, Shrestha 2016; Jagat Deuja. CSRC. Personal Interview. November 1, 2017; IOM 2016; Acharya 2017)

Land is a critical resource in Nepal. Poverty is significantly correlated to the size and quality of landholdings. Chronic land issues such as highly skewed landholdings, landlessness, lack of secure tenure rights and exploitative tenancy relationships fueled a decade-long conflict between the Government of Nepal and the Communist Party of Nepal (Maoist). The same issues continue to exist more than ten years after the signing of the historic Comprehensive Peace Accord (CPA), despite scientific land reform being a central theme of the agreement. Dual ownership still exists despite government efforts to end it, and many unregistered tenants have not received their land documentation. ‘Fake’ landless people (especially ones with political connections) have emerged and threaten to seize the benefits that should be provided to the actual landless. The second highest number of all formal court cases are land related. These cases clog up the courts and usually take a minimum of one year to solve. Successful community-led land rights commissions exist in dispersed areas and have not been able to expand nationally due to logistical and financial constraints.

Digitization of land registration, revenue and cadastral information has begun, and the first round of existing data has been computerized in all 129 land revenue and survey offices, except for Achhaam and Arghakhanchi. However, only 19 such offices have fully adopted digital systems, which means that the remaining offices continue to use traditional manual methods of recording land transactions. This means that the existing digital systems quickly become outdated and contain inaccurate information. Additionally, the land revenue and survey offices maintain separate systems and the formation of an integrated digital information and cadastral system still seems to be a distant reality. Merging these two systems would put all land related local offices under one office, improving, making it easier for the general public to access accurate information and help prevent the problems (such as dual ownership) that arise from mismatched data. The Department of Land Information and Archives lacks a research wing; thus, all current digitization efforts are being conducted with little to no research on what works to support transparent, cost-effective and accountable systems

The Government is in the process of revising the legal and policy framework governing land. So far, critical land-related policies such as the sixth amendment to the 1964 Land Act, the amended Land Use Policy of 2015, the Reconstruction Action Procedure of 2016, and the Agricultural Development Strategy of 2015 have been approved. National land policies such as the Land Policy, Land Use Act and the Bonded Labor Bill have been formulated but not yet passed. The Land Use Policy which was passed in 2013 and amended in 2015 has not yet been implemented to date, since the Land Use Act has not passed (Basnet 2016).

Rapid and haphazard urbanization is occurring as a result of lack of economic and social opportunity in rural areas. Housing plans are developed on fertile land, which poses a threat to food security. Currently, the need for housing outpaces supply; the majority of urban residents live in substandard housing in informal settlements. The settlements are mostly un-serviced, vulnerable to outbreaks of disease, and to earthquakes and flooding. The Urban Planning and Development Act, Building Code for Nepal 2015 has provisions for encouraging low-cost housing alternatives through public-private partnerships.

Nepal’s land and other natural resources are threatened. Much of the forestland between the Himalayas and the lowland plateaus has been cleared for crops, livestock, and human settlement. Landslides, erosion, and soil degradation are common. Nepal’s abundant surface water resources have been harnessed to provide energy to many areas but are increasingly polluted by the discharge of untreated human and industrial waste.

However, Nepal’s forest land has increased by more than 5 percent in the recent years. Nepal’s community forest program, which is implemented by 19,439 Community Forest User Groups (CFUGs) countrywide, has been credited with reversing the pace of degradation and deforestation in some of the country’s forests. The community forest program has also given rise to Nepal’s largest civil society organization, the Federation of Community Forest Users, Nepal (FECOFUN) which has a membership of 13,000 CFUGs. Both the CFUGs and FECOFUN struggle with problems of elite domination and the marginalization of women, ethnic minorities, and lower castes (Joshi 2016).

Land

LAND USE

Nepal has a total land area of 147,181 square kilometers and three distinct geographical areas: the southern lowland plains (Terai plateau) along the southern border with India (20 percent of land area); the central band of foothills (56 percent of land area); and the high Himalaya Mountains along the northern border with China (24 percent of land area). The Chure Hills, a region of great ecological and economic importance, is rich in biodiversity and water reserves and occupies 13 percent of the total area of Nepal spanning 33 districts. Twenty nine percent of Nepal’s total land area is classified as agricultural land; only 1.5 percent of total land is permanent cropland (World Bank 2009a; FAO 1999a; Ministry of Forest and Soil Conservation n.d.; World Bank 2014).

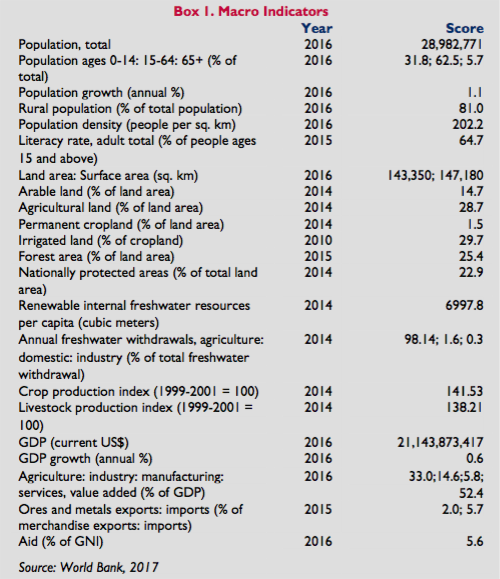

In 2016, Nepal’s population was 29 million people. The country’s 2016 GDP was $21.1 billion, with services accounting for 52.4 percent, agriculture 33 percent, and industry 14.6 percent. Twenty-five percent of the country’s population lives below the national poverty line with higher poverty rates of 45 percent in the Mid-Western region and 46 percent in the Far-Western Region. Following the 2015 earthquake, an estimated one million people were pushed below the poverty line. The rural poverty rate of 27.4 percent is almost twice as high as the urban poverty rate of 15.5 percent. While the rural poverty rates have declined, urban poverty has been increasing, as have informal slum and squatter settlements. The urban hill ecological zone has the least poor people with a poverty incidence of 8.7 percent, which increases to 22 percent in urban Terai and 11.5 percent in Kathmandu (World Bank 2016; Bakrania 2015).

Within the rural population, poverty rates are highest among landless and near-landless agricultural wage laborers (58 percent); small agricultural households (50 percent); the formerly untouchable castes (48 percent); indigenous nationalities (20–61 percent, depending on intragroup differentials); and Muslim groups (43 percent) (Nepal and Bohara 2009).

Eighty-one percent of Nepali live in rural areas, including municipalities with f rural characteristics, and 74 percent rely on agricultural land, forests, and fisheries for their livelihoods. Nepal has an estimated 2.1 million hectares of cultivable land and 22 million head of livestock. Half the population and most of the country’s agricultural production are concentrated in the Terai. Cereal crops dominate production: 35.6 percent of cropped area is devoted to rice (irrigated and rain-fed), followed by wheat (18.3 percent of cropped area), and maize (16.5 percent of cropped area). Maize and wheat are primarily grown on rain-fed land. The balance of Nepal’s production includes vegetables, pulses, oil seeds, sugar cane, and fruits (World Bank 2016; World Bank 2008; World Bank 2014; CBS 2013; ADB 2004).

Agricultural productivity is low, constrained by lack of irrigation, inconsistent access to inputs, and limited infrastructure. Agricultural extension and advanced technology suited to local conditions have not reached most rural farmers, particularly in remote areas. Market linkages are underdeveloped, and migration to urban areas is high (World Bank 2010; World Bank 2016; Sharma 2001; Silpakar 2008). Thirty percent of cultivated land is irrigated, and the efficiency of existing irrigation systems is low. Twenty percent of rural residents live more than two hours from a dirt road; 40 percent live more than two hours from a paved road. However, access to electricity for the rural population has improved drastically from only 17 percent in 2001 to 82 percent in 2016.

Large areas of private rural holdings (an estimated 17–60 percent, with the higher percentages in the hills and mountains) are uncultivated. Some land is unsuitable for farming, and some is left fallow under systematic crop rotation, but most of the land is idle due to lack of irrigation, low yields, or the absence of a family member able to farm the land (usually due to migration from rural to urban cities or foreign countries in search of employment). In some cases, landowners report not renting out idle land for fear that tenants will claim rights under land legislation that grants tillers rights to claim a share of cultivated land. Although the legislation officially ended in 2001, fear remains that the law may be re-introduced and they feel vulnerable to unfair ownership claims. (INSEC 2007; Alden Wiley et al. 2008).

About 44.7 percent land of Nepal is classified as forestland and nationally protected areas make up 17.32 percent of the total land. Timber is being harvested at a rapid rate, and much of the land in Nepal’s hills is degraded. Nepal’s annual deforestation rate is 1.4 percent. Nepal’s mountainous forest areas have frequent earthquakes, landslides, floods, and avalanches (MoFSC 2015; Karkee 2008; ARD 2006).

With a population of 1,740,977 (2011), Kathmandu is the largest urban area in Nepal, followed by Lalitpur, Biratanagar, Pokhara and Birgunj. In the past 10 years, the urban population growth rate was 3.43 percent on average. According to the 2016/17 Economic Survey, the total urban population increased to 58.25 percent from 42 percent in the previous year. Urban life in Nepal is characterized by high prices for plots, large numbers of informal settlements, overcrowding, and inadequate infrastructure. Roughly 92 percent of Nepal’s urban residents live in substandard housing (Economic Survey, MoF2016; Pokharel 2006; UN-Habitat 2001).

LAND DISTRIBUTION

Nepal’s population is predominantly Hindu; the country’s major ethnic groups are the Indo-Nepali, Tibeto-Nepali, and indigenous Nepali. Nepal has a hierarchical society; in large measure, ethnicity and caste dictate social and economic status and opportunity. Land is unevenly distributed, and the size and quality of the landholdings has always been highly correlated with economic status. Throughout the country’s history, Nepal’s elite have held the majority of land and profited from land-based resources. 19.7 percent women in Nepal own land, while 41.4 percent and 36.7 percent of Terai and Hill Dalits respectively are landless. In fact, there are 1.3 million landless or land poor people in Nepal (Karkee 2008; Savada 1991; CDSA, TU 2012; CBS 2001).

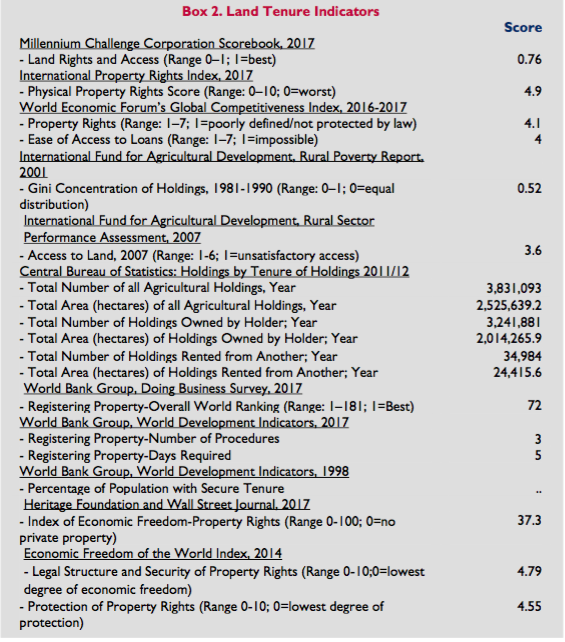

Beginning in the 1950s, Nepal made several efforts at land reforms, including the imposition of land ceilings and tenancy reforms designed to equalize landholdings. Neither approach was very effective. The ceilings were set relatively high, the legislation contained significant loopholes, and implementation of the ceiling provisions was limited in most areas. Land officials designated less than 1 percent of cultivated land as above-ceiling and redistributed only half of the above ceiling land to landless and land-poor households; the remainder continued to be held by the landowners. The state’s effort to deliver land to the tiller by registering tenants and granting them half their tenanted land has also been successful. About 541,000 tenants registered to receive land, but various sample surveys suggest that the number of tenants is at least three times as high. Some researchers suggest that the main effect of the attempted tenancy reform was to push many tenancy relationships underground. A constitutional challenge delayed awards of land to tenants. After 10 years, the government began accepting claims from tillers and landowners to end dual ownership. This claim window has been extended to August 2018.It is estimated that around 100,000 cases of dual ownership cases remain (Aryal and Awashti 2004; Chapagain 2001; Joshi and Mason 2007; Alden Wiley et al. 2008; Regmi 1976; Tika Ram Ghimire. DoLRM. Personal Interview. September 13, 2017; Jagat Deuja. CSRC. Personal Interview. November 1, 2017).

The last national survey in 2010/11 reported continuation of a significant imbalance in land distribution. The top 7 percent of the Nepalese households occupy 31 percent of the agricultural land while the bottom 20 percent own only about 3 percent. 45.7 percent of agricultural households own between half a hectare and three hectares of land and occupy 69.3 percent of total cultivable land. 52.7 percent of those households own half a hectare or less and occupy 18.5 percent of cultivable area. The average size of agricultural landholding is 0.7 hectares in rural areas and 0.5 percent in urban areas. Five percent households do not own any land but work other people’s land on a contractual basis (Nepal Living Standards Survey, CBS 2011).

The last national survey in 2010/11 reported continuation of a significant imbalance in land distribution. The top 7 percent of the Nepalese households occupy 31 percent of the agricultural land while the bottom 20 percent own only about 3 percent. 45.7 percent of agricultural households own between half a hectare and three hectares of land and occupy 69.3 percent of total cultivable land. 52.7 percent of those households own half a hectare or less and occupy 18.5 percent of cultivable area. The average size of agricultural landholding is 0.7 hectares in rural areas and 0.5 percent in urban areas. Five percent households do not own any land but work other people’s land on a contractual basis (Nepal Living Standards Survey, CBS 2011).

Eighty-four percent of farms in Nepal are owner-operated. About 10 percent of land is held under some form of registered tenancy. The actual incidence of tenancy is likely significantly higher due to the presence of informal unregistered tenants. Sharecropping is the most common form of tenancy. Landless farmers work about 2 percent of total farm holdings; most leased land is worked by households that farm their own land and rent-in additional land when they have the capacity (GON 2004; Karkee 2008; Chapagain 2001).

More than 70,000 people were displaced during the 10-year conflict (1996–2006) between the Government of Nepal (GON) and the Unified Communist Party of Nepal (Maoists). Thousands of internally displaced persons (IDPs) returned to their homes following the signing of the peace accord in 2008, often finding that their land had been confiscated or claimed by others during their absence, and they lack documentation necessary to qualify for state support for IDPs. Displaced widows are particularly vulnerable because many are unable to recover compensation for property that has been expropriated and they lack the capacity and social standing to pursue new livelihood options. Internally displaced children and women are particularly vulnerable to trafficking, sexual exploitation, and child labor (IDMC 2010).

The thousands of IDPs unwilling or unable to return to their homes joined the migration of rural residents in search of employment in urban areas, causing rapid urbanization. Although some cases of land seized by the Maoists during the insurgency (1996-2006) were settled after the Comprehensive Peace Accord, cases of both unreturned land and newly captured land remains. Informal settlements have sprung up on government and public land in urban and peri-urban areas. These settlements are unplanned, lack public services such as water, electricity, and are usually constructed of substandard housing that is vulnerable to earthquakes and floods. Twenty-six thousand people still remain displaced as a result of the 2015 Earthquake and its aftershocks. Because they lack formal land documentation they have been excluded from reconstruction and rebuilding efforts. This forces people to continue living in or move to even more risk prone areas. Furthermore, even people capable of investing in better housing and infrastructure refuse to do so for fear of forceful eviction which would lead to loss of their investments (Pokharel 2006; Paudyal 2006; Oxfam 2016).

The government recognizes the problem of slum dwellers and has started making efforts to solve this issue. The government is more open to regularizing informal settlements and is planning to approve formalization, provided the settlements are located in a safe zone. The government has also made plans to build low-cost housing options every 5 km apart in the outer ring-road periphery of Kathmandu, so the residents will be closer to their place of work. They are also considering a private-public partnership to build multistoried low-cost housing solutions; which is an excellent model to follow. While these plans are promising, it is not clear how and if they will be implemented. Some previous efforts of resettlement have failed since the residents refuse to move to a faraway location which will place them away from their income sources. One major problem is that the slum dwellers are not consulted regarding their resettlement. It is imperative to consult and educate the residents about the risks and disadvantages of the places they currently reside in, as well as to consider their concerns including proximity to work place while planning resettlement alternatives. Civil society organizations and NGOs can be good agents to encourage regular participation and representation of squatter communities (Jagat Deuja. CSRC. Personal Interview. November 1, 2017; Bakrania 2015).

LEGAL FRAMEWORK

Nepal is in the process of revising its legal framework governing land rights, with the adoption of a new umbrella land policy which is in the course of being adopted (as of 2017) along with the Land Use Act. The legal framework is expected to be governed by principles set forth in the 2015 Constitution, the 2006 Comprehensive Peace Accord and the Local Level Governance Bill which was recently passed by the Parliament in September 2017. This law has mandated local government to deal with land management issues.

The Peace Agreement called for the: (1) nationalization of forests, conservation areas, and other lands that Nepal’s monarchies had controlled; (2) end of feudal land ownership, establishment of a Land Reform Commission and adoption of a program of scientific land reform; (3) adoption of policies to provide land to landless and disadvantaged groups; (4) prevention of the ability to obtain land through corruption within government offices; (5) support for IDPs; (6) prohibition against illegal seizure of private property; and (7) support for principles of nondiscrimination (GON Peace Agreement 2006).

The new Constitution of Nepal, which became effective in 2015, grants every citizen the right to acquire, own, sell and otherwise dispose of property. The constitution also calls for equal ancestral rights to all offspring without gender discrimination and equal spousal rights to property. While Fundamental Rights Articles 40 and 26 respectively protect land rights of the Dalits and religious Guthi trusts (see “Tenure Types” for a description), there is no explicit commitment to protect the rights of genuinely marginalized landless peasants tilling land without documentation. (Basnet 2016)

Furthermore, the constitution has divided the responsibility and powers regarding land among the federation, state and local level in the following way:

Under Schedule 5, List of Federal Power – Land use policies, Human settlement development policies

Under Schedule 6, List of State Power – House and Land registration fee, Management of lands, Land records

Under Schedule 7, List of Concurrent Powers of Federation and State – Land policies and laws relating thereto

Under Schedule 8, List of Local Level Power – Land and building registration fee, Land tax (land revenue), Land revenue collection, Distribution of house and land ownership certificate

Under Schedule 9, List of Concurrent Powers of Federation, State and Local Level – Landless Squatters Management

There are currently over 60 acts that govern land and over 125 regulations that cover land-related issues. The following major laws are used by the Ministry of Land Reform and Management and its departments:

- Civil Code 1963, Muluki Ain (currently being replaced) is the criminal code of Nepal which has provisions related to land administration.

- Guthi Corporation Act 1964 includes provisions for land registered under religious Guthi (trusts)

- The Land (Measurement and Inspection) Act (1963, as amended) and its regulation 2001 sets out the classification of land and requirements for land survey and registration;

- The Land Administration Act (1963) establishes district-level land administration offices and sets procedures for maintaining land registration records;

- The Land Revenue Act 1978 and its regulation 1979 provides rules for registration, leasing and government owned lands.

- The Land Act (1964, amended 6 times) and its regulations: (a) abolishes the system of intermediaries collecting taxes from tenants by transferring control over taxation to District Land Revenue Offices and Village Development Committees (VDCs); (b) transfers land managed by the state into private land (raikar); (c) imposes ceilings on agricultural land; (d) limits rent to a maximum of 50 percent of gross annual production of main crop; (e) requires tenant certification, i.e., registration; (f) institutes a compulsory savings program; and (g) establishes a Commission on Land Use Regulation to address consolidation and fragmentation of land and incentivize farm cooperatives.

In addition to these acts; the Financial Bill 2016, Urban Planning and Development Act, Building Code for Nepal 2015 and The Agriculture (New Arrangements) Act (1963) are few of the various other legal documents that govern land issues.

TENURE TYPES

Land in Nepal is classified as: (1) private land; (2) state land; or (3) guthi land. An estimated 28 percent of land in Nepal is privately held in ownership or under leasehold.

Ownership and leasehold. Nepal recognizes two land tenure types: ownership and leasehold. Landowners have rights to exclusivity and use of their land. Landowners can freely transfer their land and pass the land by inheritance. The Land Reform Act 1984 does impose ceilings on plot size subject to various factors such as geo-ecological variations, soil types, average precipitation, other climatic conditions as well as land use types such as irrigated land, rain fed land, grazing land and average family size. The 5th amendment of the Land Reform Act reduced the then existing ceiling to 3.75 hectares in the hills, 1.5 hectares in Kathmandu Valley and 7.43 hectares in Terai and Inner Terai. Those ceilings are expected to change according to specific land-use zone since the proposed Land Policy is passed. The Land Use Policy has provisions to prevent land fragmentation under a minimal plot size specified by Specific Land Use Zones (SLUZs). An estimated 31 percent of farmers are tenants (leasing land) with the numbers as high as 80 percent in some districts. Most households renting-in agricultural land also own their own land (Chapagain 2001; MoLRM 2015; Dhakal 2011; IOM 2016; Oxfam 2016; Alden Wiley et al. 2008).

State and government land. State land includes public land (defined to include wells, ponds, pathways, grazing land, cemeteries, market areas, etc.) and government land (defined to include roads, government offices, and land under government control, such as forests, lakes, rivers, canals, and barren land, etc.). An estimated 73 percent of land in Nepal is state land (GON 2004; Alden Wiley et al. 2008).

Guthi land. Guthi land is land held by religious bodies for religious or philanthropic purposes and is not subject to taxation. Guthi land includes temples, monasteries, schools, hospitals, and farmland managed by religious institutions and individuals. About 0.03 percent of land in Nepal falls into this category (Alden Wiley et al. 2008).

Sharecropping. Most agricultural land is rented under short-term sharecropping arrangements, known as adhiya. Under adhiya, the tenant provides the labor and landowners supply some percentage of inputs. In principle, the tenant and landowner receive equal shares of the production, but the tenant rarely receives a half-share, either because he or she is in debt to the landowner or the landowner has supplied all the inputs. A second tenancy system, thekka, requires the tenant to pay a fixed share of production to the landowner. Highly exploitative systems that survived land reforms – such as those in which the tenant takes one-third or a one-tenth share – (and continuation of bonded labor) are known to exist. So far, the free Kamaiya Programme helped 26,000 former bonded labor families secure land plots. Despite efforts from the government, Kamaiyas, Haliyas, sharecroppers and small holders still struggle for land access and rights (Chapagain 2001; Alden Wiley et al. 2008; Oxfam et al. 2016; Basnet 2016).

Prior to the land-reform efforts that began in the 1950s, there were two main forms of land ownership in Nepal: raikar and kipat. Raikar land was owned by the state and cultivated by tenant farmers on long-term agreements. Raikar land included land granted to individuals or families (birta), and land given to tax collectors (jagir). These grantees served as intermediaries, taxing tenants and benefiting from their labor. Rights to raikar land could be inherited but not sold or transferred. Through legislative reforms, raikar land was converted to private landholdings (Regmi 1976; Shreshta 1990).

Nepal’s land-reform legislation converted communal land (kipat) that had historically been held by indigenous groups into state land (raikar) in the 1950s. Land-reform legislation subsequently converted raikar into private land, and a 1967 amendment to the Land Act reasserted the abolishment of all communal land. Ethnic communities lost rights to land through this privatization and the nationalization of forestland in 1957 (Alden Wiley et al. 2008; Regmi 1976).

SECURING LANDED PROPERTY RIGHTS

Land rights can be acquired by inheritance, purchase, government land allocation, or tenancy. Most rural landholdings are owned; about 72 percent of urban residents claim ownership of their plots, although their rights may be informal and hence not recognized by formal law. Most people obtain land through inheritance and the land-sale or rental markets. Roughly 20 percent of urban landowners obtained their plots through inheritance, and 23 percent rent their plots (GON 2004; Pokharel 2006; Parajuli 2007).

Urban land can be purchased or leased. Urban land – especially plots in established residential areas with services – is limited and high-priced. The vast majority of urban housing is in informal settlements on public or government land. These settlements are unplanned, crowded, and usually lack services. While these settlements can be formalized, the process must be initiated by the government and is time- consuming and expensive, involving the formation of national and district commissions, cadastral surveying, land registration, and development of infrastructure (Pokharel 2006; Paudyal 2006).

The government provided land through regularization of land settlements in the 1970s and 1980s and limited land allocations to the landless and land poor. By the end of 2016 26,532 families of freed bonded laborers have been resettled. 673 families got grants to procure land, 425 to construct homes and 647 to repair homes. Additionally, 19531 freed bonded laborers and 1142 freed land tillers got skills-oriented trainings. (Alden Wiley et al. 2006; Economic Survey, MoF 2016).

Decades of changing land laws and reforms, civil conflict, high levels of migration, and inadequate documentation of land rights contribute to a lack of tenure security. Some rural landowners allow land to lie idle rather than renting it out for fear of tenants gaining rights to the land. Those tenants who do cultivate land are often subjected to eviction every one or two years by landowners who fear tenant claims of ownership rights. The government has processes for regularization of informal settlements in urban and peri-urban areas given that the settlements are not in hazard-prone areas but there is little evidence of implementation of plans for regularization (Alden Wiley et al. 2008; Jagat Deuja. CSRC. Personal Interview. November 1, 2017).

Although Nepal has implemented a digitization process for land records, many registrations and transfers are still recorded in paper form. The records are vulnerable to loss, destruction, and distortion and misinformation. An estimated 48 percent of all landholdings are registered in Nepal, but the records often go back decades and are not considered reliable. Efforts to develop electronic information systems are underway. Currently, first round of digitization of all cadastral maps and land revenue data has been completed except in Achaam and Argakhanchi. 19 offices have moved to a digital system with the transition of 39 offices in the pipeline. However, the remaining offices still use the older manual systems with the new registrations, rendering the digital system outdated and inaccurate. An integrated system is not yet in place. (ADB 2007; Alden Wiley et al. 2008; Hari Sharan Thapa, DoLIA. Personal Interview. September 11, 2017).

Registration of land can be completed within one day with a payment of certain percentage of the property value that amounts to 5 percent in metropolitans, 4.5 percent in sub-metropolitans, 4 percent in municipalities and 2 percent in rural-municipalities. The process requires obtaining a letter from the Rural Municipality or Municipality confirming whether the land has road access; obtaining a tax clearance certificate from the local government; hiring a lawyer or scribe (lekhandas) to draft the deed; and registering the deed with the Land Registration Office, which checks the authenticity of the seller. The process also requires obtaining confirmation that the land is not under tenancy and is not mortgaged. In order to obtain an ownership certificate, the new owner must provide a Citizenship Certificate and photographs – requirements that discourage the poor from registering land. Most landowners have not registered their landholdings. An estimated 1.6 to 2 million urban and rural households have been living on public land (including river banks and roadside areas) for generations but do not have registered land rights (DOLRM 2017; Ministry of Finance 2017; The World Bank 2016; Alden Wiley et al. 2008).

Foreigners cannot own or rent land in Nepal. Foreigners may acquire land in the name of a business entity registered in Nepal; however, they may not acquire land as personal property. However, it is widely believed that foreigners own and rent land on the informal market (Chapagain 2001; USDOS 2010).

INTRA-HOUSEHOLD RIGHTS TO LAND AND GENDER DIFFERENCES

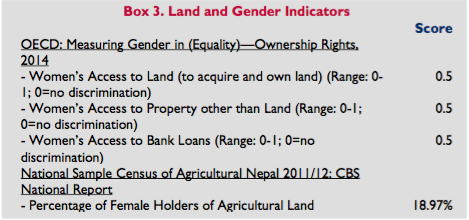

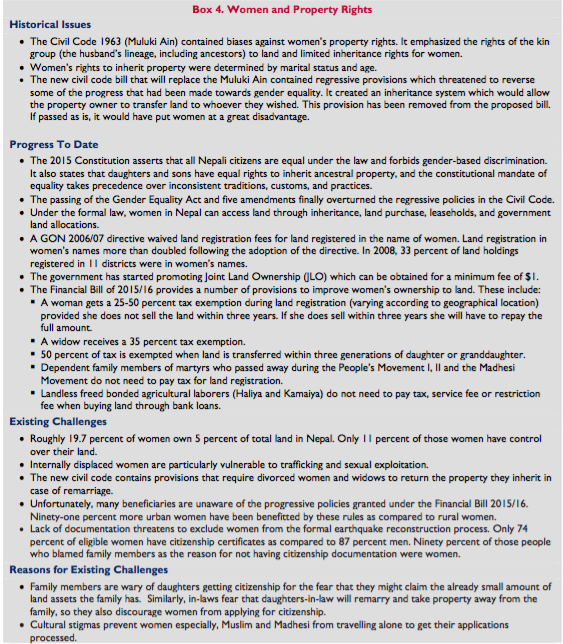

Under the formal law, women in Nepal can access land through inheritance, land purchase, leaseholds, and government land allocations. The 2015 Constitution provides that all Nepali citizens are equal under the law and forbids gender-based discrimination. The Constitution states that daughters and sons have equal rights to inherit ancestral property, and the constitutional mandate of equality takes precedence over inconsistent traditions, custom, and practices (GON Constitution 2015).

Roughly 19.7 percent women own 5 percent of total land in Nepal and only 11 percent of those women have control over their land. Women’s land ownership is highest in urban areas in the eastern part of the country. In 30 percent of the households in Kathmandu and Kaski, women own some land (Oxfam et al. 2016; Alden Wiley et al. 2008).

Roughly 19.7 percent women own 5 percent of total land in Nepal and only 11 percent of those women have control over their land. Women’s land ownership is highest in urban areas in the eastern part of the country. In 30 percent of the households in Kathmandu and Kaski, women own some land (Oxfam et al. 2016; Alden Wiley et al. 2008).

A GON 2006/07 directive waived land registration fees for land registered in the name of women, the disabled, and members of disadvantaged groups. Land registration in women’s names more than doubled following the adoption of the directive. In 2008, 33 percent of land holdings registered in 11 districts were in women’s names (Alden Wiley et al. 2008).

The Financial Bill of 2015/16 provides a number of provisions to improve women’s ownership to land. The government promotes Joint Land Ownership (JLO) which can be obtained for a minimum fee of $1. A woman gets a minimum of 25-50 percent tax exemption during land registration (varying according to geographical location) provided she does not sell the land within three years. If she does sell within three years she will have to repay the full amount. Women who fall under the category of senior citizens, disabled people, Dalits or highly marginalized people receive a 25 percent tax exemption, which is the same as men in the category. A widow receives a 35 percent tax exemption. 50 percent of tax is exempted when land is transferred within three generations of daughter or granddaughter. Dependent family members of martyrs who passed away during the People’s Movement I, II and the Madhesi Movement do not need to pay tax for land registration. Landless, freed bonded agricultural laborers (Haliya and Kamaiya) do not need to pay tax, service fee or restriction fee when buying land through bank loans. Ninety-one percent more urban women have been benefitted by these rules as compared to rural women. However, many beneficiaries are not aware of the progressive policies granted under the Financial Bill 2015/16 (Basnet 2016).

Under Nepal’s Civil Code (1963), known as Muluki Ain, women have the right to own and control their personal property, marry freely, and to remarry following divorce or widowhood. The Civil Code contained biases against women’s property rights by emphasizing the rights of the kin group (the husband’s lineage, including ancestors) to land and limiting inheritance rights. Women’s rights to inherit property were determined by marital status and age. These regressive provisions were finally overturned after five amendments and recent passing of the Gender Equality Act. However, the new civil code bill that will replace the Muluki Ain contains regressive provisions which threaten to reverse some of the progress that has been made towards general equality. The provisions include conditions that require divorced women and widows to return the property they inherit in case of remarriage. Additionally, it also creates an inheritance system which would allow the property owner to transfer land to whoever they wished, which could put women at a disadvantage. However, these inheritance provisions have been taken out of the proposed bill (FWLD 2002; Landtenure. Info 2008; Gilbert 1992, Mulmi. The Kathmandu Post. February 9, 2017; Phuyal. Kantipur. September 7, 2017).

The reasons women do not own land include a perception that society is patriarchal, women risk divorce if they ask for land, there is not enough land, and women do not feel the need to own land. Women also cite cumbersome government processes for their low levels of ownership, lack of support to implement laws providing for the rights of women, and concern in families that women owning land will deprive the family of an asset in the event of remarriage (Alden Wiley et al. 2008).

LAND ADMINISTRATION AND INSTITUTIONS

The Ministry of Land Reform and Management is the main government entity that oversees all land-related issues. It has four departments: the Survey Department, Department of Land Reform and Management, Land Management Training Center and the Department of Land Information and Archive. The Survey Department and Department of Land Reform each have 129 offices under them. A separate Land Use Council has been established to implement the land use program.

These institutions have a number of problems that hamper their efficiency. Firstly, they lack the manpower; particularly skilled human resources including surveyors and engineers with technical expertise required for the volume and nature of the work that needs to get carried out. Secondly, they lack investment in building capacity of their existing staff. There have been cases where tasks which took a couple hours using traditional methods now take 2-3 days due to staff’s technical limitations and unfamiliarity with the digital transition. Thirdly, the cadastral mapping method that is currently used is very expensive and slow. Faster and cheaper methods that serve the same purpose exist and should be used. For example, mountainous cadastral mapping can be done using drones or Google imagery; while other location-appropriate methods should be used for different parts of the country. Furthermore, context-based land administration should be adopted. The Fit-For-Purpose Land Administration approach would be faster and cheaper than the existing traditional methods and would also forego the current limitations on formal and informal land tenure systems. This would thus make implementation of new policies and realization of goals for better land governance initiated by the new Constitution, proposed Land Policy and new Local Governance Act in light of the new government system much more effective. (Jagat Deuja. CSRC. Personal Interview. November 1, 2017)

Other Ministries involved in land-related administration include: the Ministry of Agriculture and Cooperatives, Ministry of Irrigation, Ministry of Finance, Ministry of Home Affairs, Ministry of Peace and Reconstruction, Ministry of Urban Development, Ministry of Forest and Land Conservation, Ministry of Physical Planning and Construction, Ministry of Federal Affairs and Local Development, Ministry of Industries and Ministry of Law and Justice. The formal mechanisms for dispute resolution regarding land are carried out through the District, Appellate and Supreme Courts.

LAND MARKETS AND INVESTMENTS

Nepal’s market for land sales is active in both rural and urban areas, but the bulk of sales transactions are in urban land. Land values have been rising, particularly since the end of the civil conflict and in the Kathmandu Valley. (Acharya 2009; Alden Wiley et al. 2008; Basnet 2016).

In urban areas, the rising population has outpaced development of residential areas. Land developers often sell land without verification of boundaries and based on inaccurate documents, including maps. The unregulated practices are leading to sprawling, unplanned urban development, land disputes, and insecure tenure (Acharya 2009).

The land-lease market is also active, with a national estimate of 30 percent of the rural population renting agricultural land. Almost all rural land is rented under sharecropping agreements rather than for monetary payments (GON 2004; Alden Wiley et al. 2008).

The commercial banks have almost doubled their investments in land from $275,272 to $388,793 from 2014 to 2016. The easy availability of real estate and housings loans has increased commercial pressure on land to the point where most agricultural land is being used for non-agricultural purposes. There is a massive mismatch in the government valuation and real market valuation of land because government valuation is usually outdated and much lower in value. This greatly increases the profitability of prosperous land owners and land plotters (Basnet 2016).

COMPULSORY ACQUISITION OF PRIVATE PROPERTY RIGHTS BY GOVERNMENT

The Constitution of Nepal allows the state to acquire land if such acquisition is in the public interest. Public interest is, however, undefined which raises concerns around inappropriate transfer of land out of the hands of some to the benefit of others. The government must compensate landholders for any land-taking, including any acquisition in the course of land-reform initiatives set by the law (Art 25 of the Constitution).

The Land Acquisition Act of 1977, governs the compulsory acquisition of land and is consistent with the Constitution to the extent that it provides that land may be acquired for any public interest, subject to compensation. Under the Land Acquisition Act, compensation to landholders must be paid in cash at current market value, although there is provision for in-kind compensation in some circumstances. Article 25 (3) of the Constitution states that the basis of compensation and relevant procedures shall be prescribed by the act. The Council of Ministers has approved the land acquisition guideline to facilitate rehabilitation and relocation of earthquake victims through expedited private land acquisition. The new governance structure might change the existing legal and institutional mandate on securing land and property rights in the near future (ADB 2006; GON Land Acquisition Act 1977; NRA 2016; The Himalayan Times, 24th February 2016).

The 1964 Land Act, as amended, requires the state to recognize the rights of registered tenants on land. The state must compensate landowners and registered tenants for any land expropriation, dividing the compensation equally between them (ADB 2006).

LAND DISPUTES AND CONFLICTS

HISTORICAL LAND-RELATED CONFLICTS

Throughout Nepalese history land has served as a political tool used by oligarchic rulers to reward select classes in society by providing them with a stable income. Conflicts and disputes related to land can be traced back to the unification of Nepal. In the 18th century, Prithvi Narayan Shah started granting land ownership titles to those who favored him, and a feudal land tenure system became even more prominent during the Rana Regime (1846-1951). The Rana rulers captured two thirds of the agricultural and forest land and distributed the rest to private individuals. They also established numerous land use systems including Jimidari, Birta, Jagir, Rakam, Kipat and Guthi discussed above. These were highly corrupt arrangements which placed land ownership in the hands of the political elite who exploited unpaid labor and poor peasants. (M.C. Regmi 1976; IOM 2016)

The end of the Rana Regime in 1951 paved the way for a land reform program by King Mahendra who claimed to implement reforms through the Panchayat System. The Panchayat System was a party-less institution where the monarch held absolute authority over the parliament, cabinet and government institutions. The system which existed from 1960 to 1990 suppressed free press and civil liberties, rendered all political parties illegal, and jailed major political leaders. He abolished the Birta, Jagir, Rakam and Kipat systems as well as introduced the Agricultural Reorganization Act of 1963 and the Land Reform Act of 1964. The Land Reform Act is designed to “divert ‘inactive’ capital and labor from land to other economic sectors, bring about an equitable distribution of cultivable land, improve the standard of living of ‘actual tillers’ who depend on land for their livelihood, and maximize agriculture production.” Although the reform emphasized providing security to tenant farmers and providing land to the landless through ceilings on land holdings, the Panchayat’s practices of seizing land in the name of the landless kept feudalism alive under a different ruling class. (IOM 2016; Sharma and Khanal. 2010)

In the 1990s, multiparty democracy brought hope for proper land reform. However, lack of political will kept land-related proposals from being implemented. Landlessness issues and discriminatory land practices, even bonded labor – despite being abolished by the government – continued. This fueled resentment within the CPN-Maoist and in 1996, became the basis for their 40-Point Demands. The party demanded “land under control of the feudal system [be] confiscated and distributed to the landless and homeless and for land belonging to certain classes of people to be confiscated and nationalized.” In order to strengthen their supporter base and advance their agendas, the CPN-Maoist seized land from large landowners, political opponents and the government and distributed it to poor landless farmers. The signing of the Comprehensive Peace Accord (CPA) in 2006, marked the end of the decade-long armed conflict; and government committed to social transformation including land reform; Maoist committed to returning the land captured during the conflict. (IOM 2016; The Carter Center 2012)

CURRENT STATE OF LAND RELATED CONFLICTS

Land-related conflicts is a major ongoing problem in modern Nepal, with inequality in land ownership driving tensions between marginalized communities and the elites. In 2016, there were more than two hundred thousand land cases that were registered in courts (Supreme, Appellate and District), land registration and land reform offices. Land-related cases account for the second highest percentage of all cases registered in courts. About 26 percent of land-related cases go to formal courts, which usually a minimum of one year and often several years to resolve. These formal cases are very expensive and require substantial amounts of time and knowledge which puts the poor, marginalized and landless people at a disadvantage. Therefore, these groups of people pursue claims in more accessible forums including District Department Offices and Community Land Rights Coordination Committees. Although historically Village Development Committees (VDCs) and Municipalities had the power to handle land disputes related to boundary issues and encroachment, their poorly trained staff, complicated and slow decision-making processes force people to look for alternate or court-based solutions for even minor problems. We have yet to see how the judiciary under the local government carries out its duties of handling land conflicts in their respective jurisdictions under the new federal system; and whether or not they face the same problems that VDCs before them did. (Oxfam et al. 2016; Basnet 2016; IOM 2016)

The International Organization of Migration has identified five main categories of land conflict in Nepal: (1) conflict between the citizens and government agencies, (2) between individuals or family members, (3) between two or more groups in the community, (4) between tenants and land owners, and (5) between people squatting on unregistered land and the government agencies or people who hold registered land. A large number of land cases are attributed to the lack of reliable land records, high amounts of migration during the conflict period, increasing pressure on land and limited access to natural resources. Additionally, a substantial number of land disputes relate to disagreements within families over succession. Property disputes among landlords and tenants are also common. Dual ownership, which was officially abolished in 1996, still creates conflicts between owners and tenants. While unregistered tenants are fighting for protection of their tenancy rights, land owners have started eviction actions without paying tenants compensation, because they fear losing 50 percent of their land. Additionally, widespread fear of property claims from sharecroppers have made landlords hesitant to rent out land. The law creates incentives for them to leave arable land barren. (IOM 2016)

The devastating 2015 7.6 earthquake displaced more than 117,000 people, 26,000 of whom were still displaced one year later. The lack of land ownership certificates has deprived a large number of people from receiving government grants to rebuild, forcing them to settle in informal, oftentimes risk-prone settlements. The government has also destroyed and evicted 713 marginalized, landless households for encroaching on community or state forest. Despite their potential, Landless Squatter Resolution Commissions (LSPRCS) are highly ineffective political entities that have not stemmed the problem of “fake” landless people applying for and receiving benefits. The latest LSPRC formed in 2014 has been dissolved while conflicts over fake ownership continues.

Although the CPA calls for returning land captured during the conflict-era the Baidya and Biplav factions deny land return and in fact are still involved in re-capturing of land, demanding for Scientific Land Reform before any returns. These on-going conflicts not only create adverse socio-economic impacts through increased costs, loss of property, slowed investments and reduced tax income for the government; they also contribute to a loss of traditional livelihood opportunities for farmers who struggle against landlords and the State. These disputes disrupt social harmony, community relationships and people’s trust in both state mechanisms and each other which leads to extremely fragile socio- political communities and a more fragile nation. (Oxfam et al. 2016; Basnet 2016; Wehrmann, 2008; IOM 2016)

ANALYSIS

The land administration and information system, land tenure, land laws/policies, natural resource management as well as prevailing social norms and practices all collectively frame the current land system in Nepal. Problems and faults in each of these individual sectors contribute to the large number of existing land related conflicts in the country.

Land Administration System

Land issues in Nepal face many administrative hurdles. Lack of coordination and communication between concerned agencies, administrative corruption, organizational politics/power struggles, insufficient manpower leading to heavy workload, unskilled staff and lack of proper technology are key problems. With more than 450,000 registrations each year in addition to other land-related transactions, land administration is one of the busiest administrative bodies in Nepal. There are currently 129 separate Land Revenue Offices and Survey Offices, however these do not satisfy current demand for efficient registration. People have to travel long distances to get to these offices. Moreover, they have to visit and sometimes revisit both the Land Revenue and Survey Offices and face problems due to the overlapping roles of the two offices. This is burdensome for the general public and these problems could be avoided if the two offices were merged. (IOM 2016; DOLIA n.d.; Hari Sharan Thapa, Kumar Rajbhandari, Ramesh Luitel. DoLIA. Personal Interview. September 11, 2017)

Land administration is highly centralized in Nepal. Although the Ministry of Land Reform and Management has subsidiary offices all over the country, decisions relating to land management are ultimately taken at the Ministry Level. Government land offices lack institutional capacity and trained staff to effectively address many of the land cases reported to their offices. Government offices do not have dedicated staff trained in matters relating to land grievances even though they are required to. The Mediation Act 2014 calls for community-led land governance. Projects such as Oxfam’s Community Land Rights Projects have been working on dispute resolution through Community Land Rights Coordination Committees, however these have been limited to a small number of districts. Furthermore, similar community mediation programs face numerous logistical and financial challenges such as lack of proper office space, management of transportation and subsistence costs to quickly scale up their programs to a nationwide network. Given these problems, cases get escalated up to the Supreme Court. This clogs up the formal court system with hundreds of thousands of land-related cases each year (Basnet 2009; Oxfam 2016; IOM 2016)

Land Information System

The vulnerability of traditional paper-based land record systems has contributed to numerous conflicts. Historically, claims of stolen, inadequate and even fraudulent land records have been common and accountability for these problems has been quite limited. Furthermore, technical errors in the cadastral maps have led to many boundary disputes. The Land Revenue Office records and the Survey Office cadastral maps differ. This leads to conflicts between parties when landowners claim more land than they actually own on the basis of faulty cadastral maps. Department of Land Information and Archives lacks a research department so all work they carry out has been done without proper maps and land information, creating opportunities for errors. (IOM 2016; Ramesh Luitel. DoLIA. Personal Interview. September 11, 2017)

Additionally, the records kept in the land revenue and survey offices are not up-to-date and consistent. Recognizing the demand for a modern digital land information system, the Department of Land Information and Archives has started the digitization process in both offices. Low capacity means that some digitized records contain conversion mistakes and. Currently the government has introduced digital processes in 19 offices, with another 39 in the pipeline waiting for adequate trained staff. This means that there has been and continues to be a time-lag between the time records were entered in the system and the time the office staff acquire necessary technical capabilities, so all new registrations are excluded from the digital system and are still being conducted manually. Even in offices that have gone digital, there are problems of overworked staff, (records now have to be recorded both manually and digitally which requires double efforts). Moreover, the Revenue Offices and Survey Offices use different software systems and the formation of an integrated system is not imminent. This means historical problems of mismatched records between the two offices will continue. (Tika Ram Ghimire. DoLRM. Personal Interview. September 13, 2017; Hari Sharan Thapa, Kumar Rajbhandari, Poshan Niroula, Ramesh Luitel. DoLIA. Personal Interview. September 11, 2017)

Finally, problems of verifications may lead to conflict between land owners and government officials and occasionally between two individuals or households. For example, people sometimes have different names on their land certificate and citizenship card, making the authentication process complicated. In some cases, land belonging generally to a weak or illiterate household or person may be recorded fraudulently under another person’s name. The future direction of land administration and the land information system depends on what roles the newly formed local governments and provinces will carry out. (IOM 2016)

Land Tenure, Land Laws and Policies

The 1996 fourth amendment to the Land Reform Act of 1964, called for an official end to dual ownership in land. The reform was designed to put land in the hands of actual tillers and boost agricultural production. The provision called for an equal distribution of land between the tenant and owner. Importantly, all claims had to be made within 6 months of the amendment, after which time tenancy rights would be terminated. Many tenant families were not officially registered as dual owners at the time and only had temporary proof from a recent cadastral survey. This made them ineligible to claim ownership within the specified time. The process hence left a large number of pending cases which still remain unresolved. Additionally, the amendment also terminated the tenancy rights of 500,000 unregistered farming families who were evicted by landlords from the lands they had tilled for years. This has caused significant conflict and contributed to fragility in the country. Existing dual ownership cases not only decrease agricultural productivity and harm food security, they also divert time and capital that could have been put to other productive uses. (Sharma and Khanal 2010; IOM 2016)

The 2015 earthquake has left marginalized landless squatters more vulnerable since it has exacerbated their already harsh living conditions. Post-disaster reconstruction efforts exclude them since they do not have proper documentation of land ownership. There are still many people living in camps for Internally Displaced People, because they are unsure whether or not their land is safe. A verification of safety would enable the financially secure families to start the process of rebuilding on their own homes or would encourage building in alternate settlements if lands are deemed unsafe. (Oxfam et al. 2016)

Despite land being in the heart of all development talk in Nepal, the issue of landlessness and marginalized farmers still remains a crippling problem. Election campaigns paint the landlessness problem as the number one priority, however little progress is made. Informal tenure is not recognized by the government and hence without legal documentation the risk of eviction always looms. Laws and policies which aim to grant the right of access to land and housing to the landless exist but have not been implemented properly. The 2015 Constitution states that the government should provide a one-time land grant to the landless Dalits. Furthermore, the 2015 Land Use Policy and the 2012 National Shelter Policy both include strategies to provide small plots of land and low-cost housing options to vulnerable families. In reality, conflict between the Government and the landless people has ensued with the Government forcefully evicting landless people without any compensation or resettlement options. Homes have been destroyed and peaceful protests suppressed and disrupted (IOM 2016; GON Constitution 2015; Oxfam et al. 2016).

The Landless Squatter Problem Resolution Committees (LSPRCs) were formed with the aim of solving the problem of landless squatters. The committees are supposed to take applications from the landless, issue identity cards and provide solutions. However, these entities have been politicized, and used as a means for political parties to provide jobs to their members. Not only do the staff of LSPRCs lack relevant skills, they lack motivation to solve the issues at hand. This leads to numerous cases of “fake landless” who easily get the identity cards and land plots, while the landless remain vulnerable and at risk. Even though three different High-Level Land Reform Commissions have been formed, proper implementation of their recommendations has not occurred and the last-formed LSPRC has been dissolved (Khim Lal Devkota. Personal Interview. September 7, 2017; Basnet 2016; IOM 2016).

Land grabbing has been rapidly increasing in the country. There are a number of agents involved, including federal agencies, development projects, security forces, ethnic groups, educational institutions, religious organizations, private sector including industries, political trusts and factions of the Maoist Party. The kinds of land that have been captured are private, state and forest land. A large amount of cultivable land has been converted to be used for non-agricultural purposes; and a substantial amount of such land is left idle and unproductive. This poses a serious threat to food production. Often locals sell their land for very low prices in hopes of securing jobs. In other cases, they are forcefully removed with little to no compensation. The promises of job opportunities rarely pan out and farming families that were once self-sustainable are left having to depend on the market for food consumption. Such grabbing has also rendered tribal groups like the Chepangs landless as they are denied the rights to land that they have occupied for generations. Additionally, real estate developers buy lands from the locals at extremely low prices, then sell them at hefty margins. This puts the security of tenure of poor and vulnerable groups at risk and creates conflict (CSRC 2014).

Currently, companies are allowed to occupy land above specified ceilings if they procure permits to do so from the government. However, such land can only be used for the specified purpose. Changing the use of land for other commercial or agricultural purposes is very burdensome. For example, if a farmer would like to add banana farming to his tea plantation, the decision would have to be passed through the cabinet. Furthermore, if any industry would like to sell their land and move to another area given the rising real estate prices, they are not allowed to do so. Even if the industry closes down, all of its land has to be handed over to the government. This creates conflict between business owners and the government regarding who gets full rights over the land in case of closure or transfer of the industries. There have also been cases where this has been allowed which brings the focus to how the rules can bend depending on personal ties and informal settlements.

Around 25-28 percent of arable land in Nepal is left barren. Farmers lack the financial capabilities to invest in land and also face huge risks when finding a market for their produce. Contract farming could be an excellent way to solve this problem whereby investors provide inputs, finances and the technical know-how and farmers in turn sell them their produce at pre-specified quantity, quality and price terms. Although contract farming has already been practiced in some places, a formal act concerning contract farming agreement is not in place. The Agriculture Enterprises Promotion Act includes provisions for contract or lease farming; but this draft still needs to be reviewed by stakeholders for feedback which will be a lengthy process. This opens both famers and investors to risk and conflict as they have to do business purely on the basis of trust for the time being. Secondly, there is a problem of the absentee landlord. The landlords are hesitant to rent out their land for agricultural purposes due to the fear that sharecroppers might claim their land, therefore they leave their land barren. Landowners also evict existing unregistered tenants on a regular basis for the same reasons thus creating conflict. This is reflective of weak property rights and unstable politically skewed land governance. Arable land left fallow is a loss not only in terms of food security and agricultural productivity but also a loss of economic opportunities for both the landowners and potential sharecroppers (Jagat Deuja. CSRC. Personal Interview. August 7, 2017; Acharya 2017; IOM 2016).

Natural Resource Management

Forests are an important source of livelihoods and economic sustainability in Nepal. Not only are they a vital source of food, animal feed and medicinal herbs, they are also a rich source of timber and wood which are used for building, construction and cremation of the dead. However, forest resources are vulnerable to illegal, unauthorized harvesting and smuggling of forest products. This degrades forest blocks and causes conflict between the Community Forest User Groups (CFUGs) and illegal traders. Additionally, landless people often occupy and build their homes in forest areas. CFUGs believe this to be an infringement on their forest rights, so conflict between them and the landless is a common occurrence. According to the CFO Land Reform Monitoring Report, the government has evicted a total of 713 landless and marginalized households living in forest land and community forests by destroying and setting fire to their houses in the process (IOM 2016; Basnet 2016).

Social Norms and Practices

Women: Generations of gender disparity have caused many problems relating to land rights for women. The problems were exacerbated by the earthquake as lack of documentation threatens to exclude women from the formal reconstruction process. For example, only 74 percent of eligible women have citizenship certificates as compared to 87 percent men. Ninety percent of those people who blamed family members as the reason for not having citizenship documentation were women. Family members are wary of daughters getting citizenship for the fear that they might claim the already small amount of land assets the family has. Similarly, in-laws fear that daughters-in-law will remarry and take property away from the family, so they also discourage women from applying for citizenship. Furthermore, cultural stigmas prevent women especially, Muslim and Madhesi from travelling alone to get their applications processed. Additionally, husbands of 32 percent of the married women have migrated abroad or to bigger cities in search of employment. This makes it difficult for these women to get their documentation (Oxfam et al. 2016; CARE and CSRC 2016; Inlogos 2017).

Although legislations and policies have gradually changed towards improving land rights for women, they have yet to be implemented properly. Furthermore, strongly rooted cultural norms mean that people choose not to take up the positive policies even though they might be in place. Without land entitlements, women and girls continue to be victims of domestic violence, illiteracy, forced marriage, inequality and subsequently poverty (GON Constitution 2015; Basnet 2016; Oxfam et al. 2016).

Indigenous People: Indigenous people are the original settlers who resided in Nepali soil long before the formation of Gorkha and subsequently Nepal. Not only do they have their own culture, language and religion but also have a unique and special relationship with their land. The territories they occupy are at the core of their tradition and beliefs; so they largely depend on natural resources and their lands for survival. Since indigenous people (IP) and their rights are so closely tied to land resources, the ILO Convention 169, though supportive of the Eminent Domain principle, under which the State retains the sovereignty over natural resources to use it for public benefit. lays down grounds to empower the IPs. Under “Convention 169 (Article 15 (2)), the State is obliged to establish procedures through which it shall effectively consult the indigenous peoples concerned, with a view to ascertaining whether and to what degree their interests would be prejudiced, before undertaking or permitting any programs for the exploration or exploitation of such resources pertaining to indigenous people lands.” Furthermore, they are also to be part of benefit sharing from the utilization of natural resources wherever relevant (Roy and Henriksen 2010; Maharjan 2016).

Despite such provisions, IPs continue to face problems in practicing their collective land rights. Nationalization acts along with discriminatory common and special national laws have forced them to migrate from forest and pasture land – sources for their subsistence. 65 percent of the IP’s ancestral land are occupied by national parks and conservation areas and Tharus, Sherpas, Chepangs, Rautes have been forcefully displaced. The Nepal Federation of Indigenous Nationalities (NEFIN) thus majorly focuses on the equal and equitable distribution of land resources. Representing 37.2 percent of the total population, IP’s have emerged as a major stakeholder in the land and property discourse (Maharjan 2016).

According to NEFIN, following are some of the major claims of indigenous people:

- Right to land and natural resources: Indigenous people shall have right to ownership, utilization, consumption, management, conservation and control over their ancestral lands, territories and natural resources (therein);

- Right to self-determination: Indigenous people shall have right to self-determination. By virtue of this right they shall freely own, control, utilize, consume and manage their traditional lands and natural resources;